In this jewel box of a Byzantine church, the solid walls of a Greek-cross plan dissolve into golden light.

Basilica San Marco (Saint Mark’s Basilica), Venice, begun 1063 and Anastasis (The Harrowing of Hell) mosaic, c. 1180–1200, Middle Byzantine. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:00] We’re in the Basilica of Saint Mark in Venice. It’s called Saint Mark because it holds the body, the relic, of Saint Mark.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:14] A couple of Venetian merchants stole the body of Saint Mark from Alexandria in 829. When his body was brought back, this was obviously an incredibly important relic, and the construction on the church began soon after that.

Dr. Zucker: [0:28] Now, think about this. Saint Mark was one of the Evangelists, one of the authors of the New Testament, it doesn’t get more important than this.

[0:00] The idea of bringing his body back from Alexandria was especially important because Egypt was then controlled not by the Byzantine Empire — that is, not by the Christian world — but it was in Islamic hands.

Dr. Harris: [0:47] There is even a legend that Saint Mark had a vision that his final resting place should be in Venice.

Dr. Zucker: [0:53] Of course, these are the legends that grow up to justify these historical events.

Dr. Harris: [0:58] That’s how it seems to us, certainly in the 21st century.

[1:01] The church is Byzantine in style in every way that we think about Byzantine architecture.

Dr. Zucker: [1:15] The church that we’re in currently was begun in 1063. It replaced two earlier and smaller shrines. This does refer to the Byzantine in very direct ways. The Venetians wanted their art, their architecture, to recall not only the Byzantine, the Eastern traditions, but specifically the traditions of Constantinople.

[0:00] This church was based on the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, a church that no longer exists.

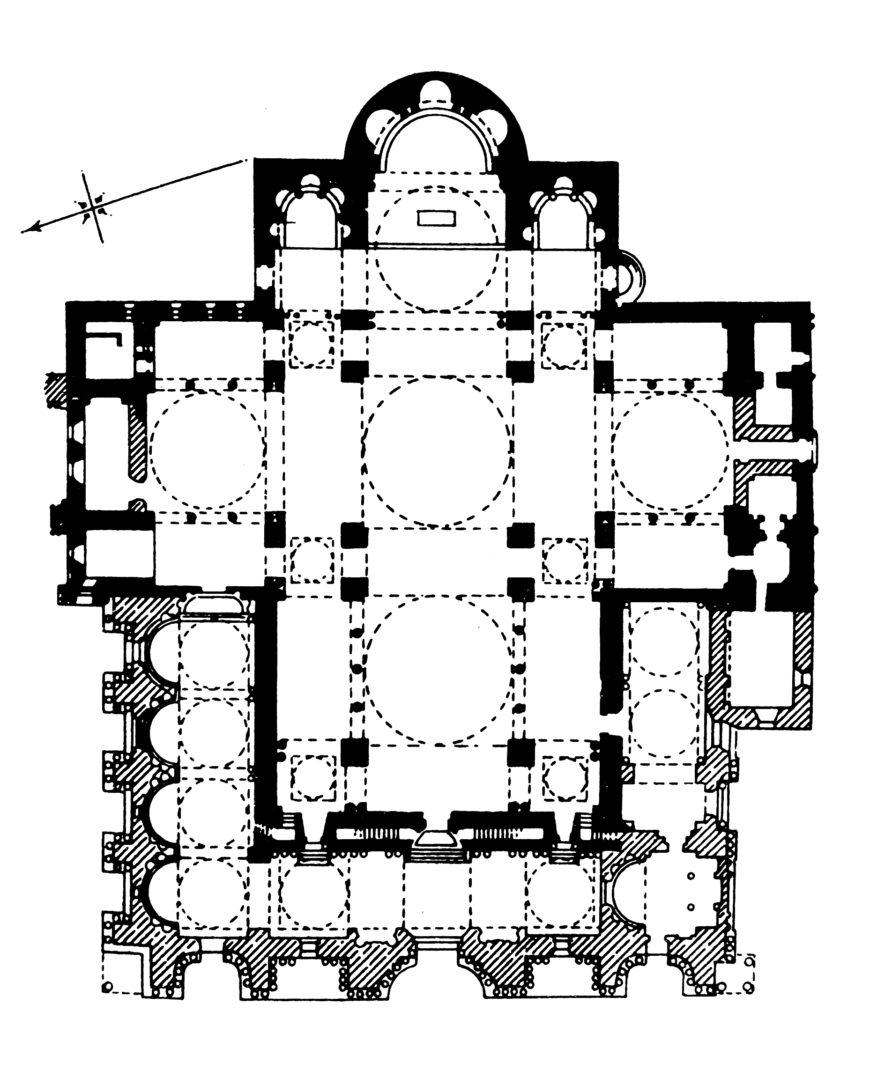

Dr. Harris: [1:36] Like the Church of the Holy Apostles, Saint Mark’s is essentially a Greek cross, a cross with equal arms, with domes over each arm and another dome over the crossing.

Dr. Zucker: [0:00] Those domes recall, very directly, the kind of architecture that we find in Constantinople — that is, a dome that has windows at its base, a necklace of light that makes the dome seem to levitate upward and not to be supported.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] That’s the idea of the whole interior, the sense of being in a golden jewel box. The walls are covered with golden mosaics, so you have this sense of what you know to be solid wall dissolving into glittering light.

Dr. Zucker: [2:18] 40,000 square feet of the surface of this church is covered with mosaic.

Dr. Harris: [2:24] The mosaics date from different time periods, but let’s take a look at an early mosaic of a subject called the Harrowing of Hell, also known as the Anastasis.

[2:34] This is Christ, who’s gone into Hell. He’s battered down the doors. He’s going in to save virtuous souls who are there because they lived before the possibility of salvation — that is, before his sacrifice on the cross.

Dr. Zucker: [2:47] In this case, you actually see Christ grabbing the wrist of Adam. Eve is just behind him. He’s going to save Adam and Eve from limbo — that is, from not being able to enter Heaven.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] You’ll notice that he’s grabbing Adam not by the hand but by the wrist. This idea that human beings can’t save themselves, but needed Christ’s sacrifice, they need Christ.

Dr. Zucker: [3:08] It’s not a partnership, in other words. It is Christ leading them out.

[0:00] Behind them, perhaps other worthy souls, perhaps Old Testament prophets. My favorite part is what Christ is standing on.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] He’s standing on Satan, whose hands are bound in chains and who’s represented in a much darker color.

Dr. Zucker: [0:00] Around him is the debris of Christ’s entrance into hell. You can see the chains strewn about. You can see keys. You can see the doors of Hell that Christ had knocked down and now forms a cross.

Dr. Harris: [0:00] All of this, of course, in this typical Byzantine style, with a gold background, with forms of drapery created by lines that are more stylized than the way drapery falls on a human body.

Dr. Zucker: [4:00] Look at Christ for a moment. If you follow his right arm, the arm that holds Adam’s wrist, look just over the elbow. You see a bit of drapery that is flying up, and it not only seems to have a life of its own, but also seems to suggest that Christ has just arrived.

[4:07] Look at the length of those bodies. Look at their attenuation. This is not the proportion of ancient Greece. This is not the Renaissance. This is that moment in the mid-Byzantine style where we see the symbolic representation of the human form, not a precise rendering that is based on observation.

Dr. Harris: [4:27] Or look at Adam kneeling, with his right knee coming to a point…

[0:00] [laughter]

Dr. Harris: [0:00] …and then his left calf and foot extending out behind him. This is not naturalism, this is a symbolic Byzantine language that we know so well.

[0:00] [music]

Exterior façade of the Basilica San Marco (Saint Mark’s Basilica), Venice (photo: Jorge Franganillo, CC BY 2.0)

An impressive building

The Basilica San Marco anchors the Piazza San Marco, the large public square that was the center of religious and political power in Venice. The church extends five portals across the width of the piazza. Five bulbous onion domes topping the structure create heft and presence. Glittering gold mosaics and multicolored marbles—both inside and out—project wealth, power, and more than a little dazzle.

The current basilica is the third iteration of the church on the site and the product of centuries of remodeling, additions, and decoration. From the Middle Ages on, the state of Venice used the Basilica San Marco to craft a civic identity and state mythology. It achieved this by appropriating both style and materials from the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, aka Byzantium. [1]

Map showing the location of Venice, Rome, and Constantinople (underlying map © Google). The boundaries of the Byzantine Empire shifted and contracted during its nearly one-thousand-year existence

A century after its 5th-century founding, the city of Venice was a minor outpost, a subordinate vassal subject to orders from the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, whose capital was Constantinople. By the 13th century, Venice had transitioned to an imperial power itself. To communicate this new status, the Basilica San Marco was adorned with spolia taken directly from Constantinople. It was a clear declaration that Venice would be controlled by the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire no longer.

Creation dome, Narthex mosaics, 13th century, Basilica San Marco (Saint Mark’s Basilica), Venice (photo: amberapparently, CC BY 2.0)

Visitors entering the narthex find themselves surrounded by mosaics decorating walls and ceiling over tessellated multi-colored stone floors swirling in varied geometric patterns. Inside, patterned marble revetment clads the lower part of the building.

Interior view of nave looking towards apse, Basilica San Marco (Saint Mark’s Basilica), Venice, begun 1063 (Middle Byzantine) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Above, gold mosaics wrap the heavy vaults and domes with a shimmer that lightens their visual weight. The tomb of Saint Mark, for whom the church is named, lies past the crossing and rood screen in the apse.

A body presents opportunities

When the body of Saint Mark arrived in Venice in 829 C.E. it was such a win that the city built an entire basilica to house it. As a vassal state in the 9th century on the far edge of the Byzantine Empire, Venice wielded little political power. Religiously, the fledgling city held no ecclesiastical control (it was subject to the competing patriarchates of Grado and Aquileia on the mainland). However, with the relics of a martyr, who was one of Christ’s original twelve apostles and one of the four evangelists, Venice could establish itself as a divinely chosen location. It could also wrest religious prominence away from the city of Grado on the mainland that was the seat of the bishop.

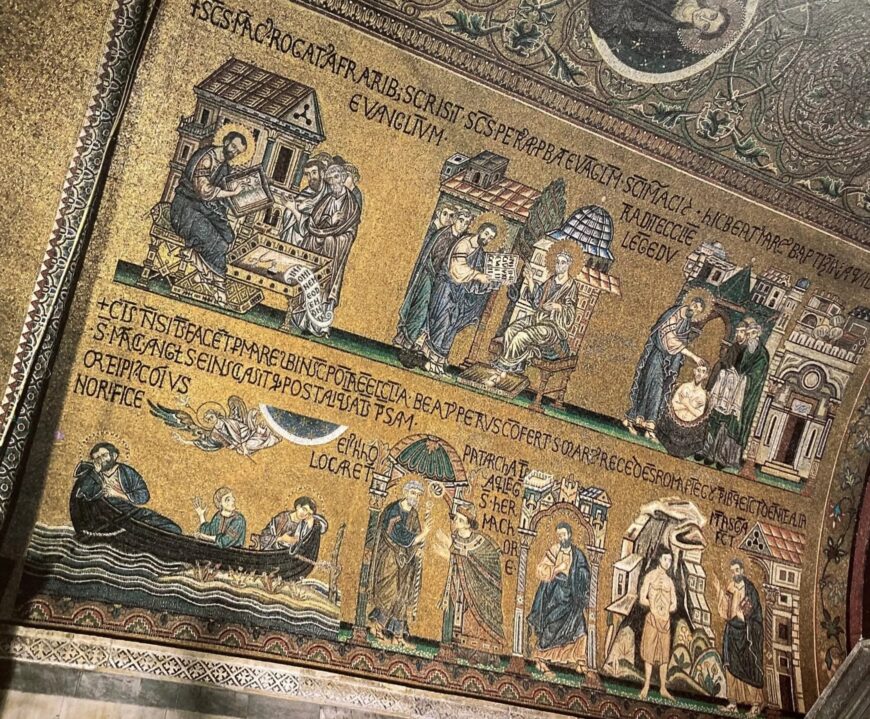

Bottom left: Dream of Saint Mark: an angel appears to Saint Mark dreaming on a boat and tells him his body will rest here—the location that will become Venice centuries after his death, Cappella Zen mosaics (Basilica San Marco, Venice)

The myth making began immediately. To counter any suspicion that the Venetians had illicitly stolen the relics (as they, in fact, had), a praedestinatio myth developed that Saint Mark had a dream prophesying that someday his body would rest in Venice (a city that did not exist during the evangelist’s lifetime).

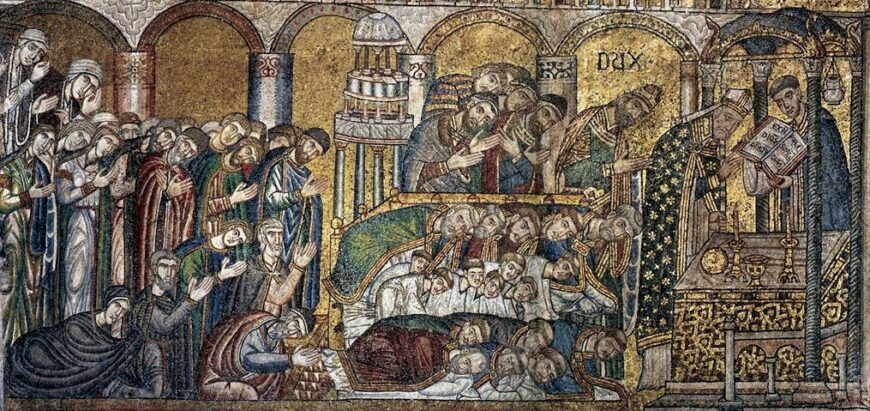

The doge (labelled “DUX” above), clergy, and patricians of Venice pray inside the basilica for the relics to be found. Preghiera, Prayers for the discovery of the body mosaic (Basilica San Marco, Venice)

Civic mythmaking

A story pointedly connecting the doge, Saint Mark’s relics, and the basilica appears on the walls of the Cappella Zen (now an enclosed chapel in the basilica, but formerly the primary entrance for visitors arriving from the water). In two mosaics with gold backgrounds, we see Venetians gathering in the Basilica San Marco. In the first scene, the Preghiera or Prayer, the doge leads Venetian patricians in three days of fasting and prayer in the partially-constructed structure. They bend heads over folded hands while clergy prostrate themselves on the floor. In the second scene (not shown), the Apparitio or Appearance, we see the clergy, doge, and patricians of Venice witnessing the miraculous opening of a column revealing the body of Saint Mark inside (before the second iteration of the Basilica San Marco was constructed beginning in 976, the relics of Saint Mark were thought to be lost). Not only did this story allay fears that the relics were lost forever (or worse, replaced with fakes), it underscored Saint Mark’s repeated choice of Venice as his body’s final resting spot and the importance of the basilica itself.

Saint Mark’s coffin enters the Basilica San Marco’s main portal. The Porta Sant’Alipio Mosaic, c. 1270–75, Basilica San Marco, Venice (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Eventually in multiple locations the basilica itself would relate the stories of how Saint Mark chose Venice—on its façade in mosaiced lunettes made in the 13th century, inside the Cappella Zen, and on the Pala d’Oro altarpiece. In Martin da Canal’s 13th-century chronicle Les Estoires de Venise, he tells readers that they can confirm his historical account by checking the Basilica San Marco’s façade. The authoritative images depict the basilica and doge in the civic myths of Venice. Far from a separation of church and state, this was a marriage of church and state.

A government chapel

From its first iteration begun in 829, the Basilica San Marco was part of the Venetian state—literally. The Basilica San Marco began and existed as a palatine chapel, that is, it was legally part of the doge’s palace, albeit a very large and exterior part for one thousand years (it was only designated a cathedral in 1807 following the fall of the Republic of Venice to Napoleon). Indeed, when the Bishop Ursus of Olivolo-Castello in Venice, received Saint Mark’s body, he led the relics in procession to the doge’s palace. [2] Over the centuries Venetian rituals that blended state, civic, and religious elements reinforced not only a bond between church and state but a lack of division at all. [3]

Mosaics on the pendentive and dome, with marble revetment visible in the lower right. Basilica San Marco (Saint Mark’s Basilica), Venice, begun 1063 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The existing Basilica San Marco has changed over its history, but the form we see today dates to its third iteration begun c. 1063 under Doge Domenico I Contarini, which significantly enlarged the building. [4] The south and north transepts were lengthened. The narthex was constructed. Piers and walls were reinforced to support the weight of heavier vaults and the domes above the decoration increased in opulence. Patterned marbles and mosaics covered every surface. Surrounded by refracting gold mosaics and wavy veined marble, the visitor can lose the sense of weight, of load and support communicated so clearly in classical architecture. Instead, the effect can be dizzying.

Basilica San Marco (Saint Mark’s Basilica), 11th century and later, Venice (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the 11th century many cities on the Italian peninsula renovated their cathedrals, but Venice’s looks decidedly different. The façade is richly decorated in antique spolia exclusively, unlike other late medieval Italian examples that included contemporary sculpture. [5] In Venice, political portrayals of a city’s history appeared in predominantly religious spaces, whereas on the Italian peninsula, they appeared in primarily civic spaces.

Floor plan, Basilica San Marco, Venice, from Banister Fletcher, A History of Architecture on the Comparative Method, 5th edition (London: B. T. Batsford, 1905)

And instead of building a longitudinal nave of the type found in Pisa, Rouen, or Santiago de Compostela in western Europe, Venice built a central plan church, a distinctly different form and one associated with the Byzantine Empire.

Illumination depicting Apostoleion in Homilies of James Kokkinobaphos, 12th century (Byzantine) (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, Grec 1208, folio 3 verso)

An Eastern model

All three iterations of Basilica San Marco directly emulate the Apostoleion, also known as the Church of the Holy Apostles, in Constantinople (capital of the Byzantine Empire). Like that church, Venice’s basilica possesses five domes, one over each equilateral arm and the crossing, a Greek cross central plan, and opulent interior mosaics. For the third and final iteration, Doge Contarini hired an Eastern architect, presumably for authenticity.

Originally founded by Roman Emperor Constantine around 330 C.E., the Apostoleion contained twelve cenotaphs for Christ’s apostles. [6]

Imitating the form of the Apostoleion enabled Venice to appropriate that church’s imperial associations as Venice pivoted from vassal state to full sovereignty and, eventually, its own empire. Viewers at the time recognized the Basilica San Marco’s resemblance to the Apostoleion. A 12th-century monk at San Nicolò di Lido in the Venetian lagoon wrote the new church was built “in a construction similar to that of the Twelve Apostles in Constantinople.” [7]

Exterior with spolia from the Fourth Crusade, Basilica San Marco (Saint Mark’s Basilica), Venice, begun 1063 (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Imperial theft

The boldest of Venetian imperial statements at the Basilica San Marco occurred in the 13th century when Venice diverted the Fourth Crusade from its intended target in the Holy Land to the wealthy Byzantine capital of Constantinople. Venetians looted heavily, shipping window screens, sculptures, columns and capitals, and even wall sections of carved stone back to Venice.

Prior to the Sack of Constantinople, Venice’s power had been growing and the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire had long conferred Byzantine aristocratic titles on Venetian doges. In recognition of Venice’s growing power, the titles increased in rank from ypatos (consul) in the 9th century until, finally, in the 11th century the title protesvastos, reserved for the emperor’s closest relatives was granted to the doge by the court at Constantinople. [8] But when Venice conquered Constantinople, the doge assumed the title “Lord of One Quarter and Half of One Quarter of the whole Roman Empire”—and kept using it even after Venice lost the Latin Kingdom in 1261. [9]

The Four Tetrarchs, from Constantinople, c. 305 C.E., porphyry, 4 feet 3 inches high (Basilica San Marco, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Notable spolia on the basilica include the Four Tetrarchs, an ancient Roman sculpture made of porphyry, broken in half to fit on the corner of the basilica treasury. The sculpture’s missing foot was found in the 20th century in Constantinople (today Istanbul).

View of the north side of Saint Mark’s Basilica with the “Pillars of Acre,” Venice (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The so-called “Pillars of Acre,” two free standing piers carved with vines and pomegranates, stand outside the basilica’s north face and actually come from the church of Polyeuktos in Constantinople. An imperial porphyry bust rests on the porch balustrade. A rare surviving quadriga (a four-horse chariot used in Roman racing) mounted on the porch facing the piazza connects Venice to the ancient Roman Empire.

Today, replicas adorn the basilica and the original can be seen inside. Horses of San Marco, 4th century B.C.E.–4th century C.E. (ancient Greek or Roman, likely Imperial Rome), copper alloy, 235 x 250 cm each (Basilica San Marco, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The 19th-century British writer John Ruskin remarked, “the front of St. Mark’s became rather a shrine at which to dedicate the splendor of miscellaneous spoil, than the organized expression of any fixed architectural law or religious emotion.” [10] Aesthetic judgment aside, the purpose of the awkward, mismatched prominence of spolia on the façade was, indeed, to declare the inversion of the political order. The vassal was now on top. [11]