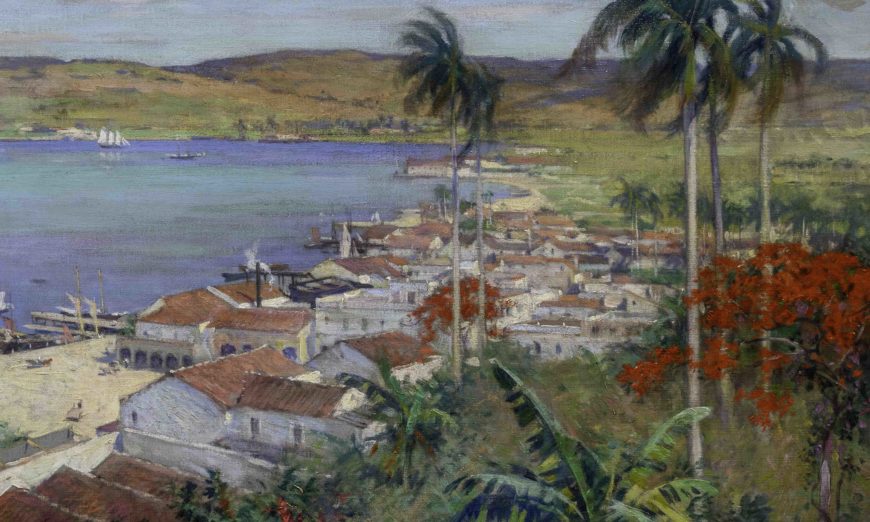

Union of the Inka Royal Family with the Houses of Loyola and Borgia, 1750–1800, oil on canvas (Church of the Compañía, Cuzco)

This important painting hangs on the walls of the Jesuit Church of the Transfiguration (today called La Compañía) in the city of Cuzco in Peru. Cuzco was the capital of the Inka Empire until the Spanish conquest in 1533. In 1568, soon after the conquest, the Jesuits arrived in Peru to convert the Indigenous population. The painting commemorates the unions of two elite families in about 1614 in colonial Peru via the sacrament of marriage. It features over two dozen figures in an expansive architectural setting. In addition to this version, at least eight other copies have been located in other Jesuit churches in Peru. The painting is a fascinating window into the power relations between the Inka, the Jesuits, and the Spanish colonial authorities.

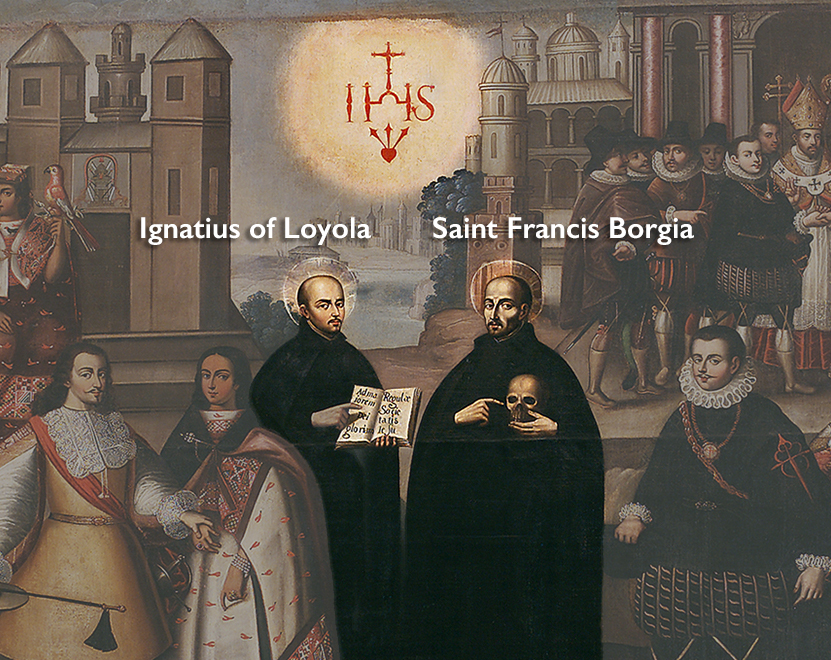

Ignatius of Loyola and Saint Francis Borgia (detail), Union of the Inka Royal Family with the Houses of Loyola and Borgia, 1750–1800, oil on canvas (Church of the Compañía, Cuzco)

In the center, we see two Jesuit saints. They have haloes around their heads, indicating their divine status, and wear black garb. The two saints peer at the viewer, gesturing to objects in their hands. At left is Saint Ignatius of Loyola, founder of the Society of Jesus (the Jesuits) whose Latin manuscript reads “Ad majoreum dei gloriam,” or “to the greater glory of God,” the Jesuit motto. At right is Saint Francis Borgia, a Spanish nobleman who sacrificed great wealth to enter the Society of Jesus, holding a skull in hand (a symbol known as a memento mori—a reminder of death). In the sky above floats the monogram of Jesus, IHS, an emblem for the Society of Jesus.

There are numerous other figures, including two couples in the foreground on either side. The cartouche at far left explains the relationship between the various protagonists.

Two unions join the Inka with the houses of Loyola and Borgia (detail), Union of the Inka Royal Family with the Houses of Loyola and Borgia, 1750–1800, oil on canvas (Church of the Compañía, Cuzco)

At left wearing an Inka style dress featuring geometric tucapu designs is Doña Beatriz Coya, an Inka princess. She holds the hand of the conquistador Martín García de Loyola, nephew of Saint Ignatius. Behind them are members of the Inka royal family who bless their marriage. On the right, we see their daughter, a mestiza named Ana María Lorenza standing behind her husband Juan Enríquez de Borja y Almansa, the grandson of Saint Francis Borgia. Behind them, we see Ana María and Juan Enríquez a second time taking their vows outside of a church in Madrid (Spain) in the right background. The painting, therefore, collapses both time (their wedding day and their future) and space (Peru and Spain), depicting people, events, and places into a single pictorial imaginary.

Union of the Inka Royal Family with the Houses of Loyola and Borgia, 1718, oil and gold on canvas, 175.2 x 168.3 cm (Museo Pedro de Osma, Lima)

A version in the Cuzco style

The version of this subject now housed in the Museo Pedro de Osma in Lima is painted in a different style. It condenses the space and omits some of the figures. The artist, however, has added copious gilding in the costumes and regalia of the figures. This use of gold leaf was a hallmark of Cuzco School painting. The Cuzco school refers to paintings created in the region of Cuzco following a legal battle initiated in 1688 by a group of Indigenous artists who complained of their treatment at the hands of Spanish members of the painter’s guild. The two groups parted ways, which paved the path for the establishment of a local tradition inflected by both Westernized styles and Andean pictorial language. Along with gilding, Cuzco school paintings came to be known for their bright color palette and Indigenous Andean symbolism. This Andean character is seen most obviously in both paintings in the resplendent Inka garb worn by Doña Beatriz and her family in the left background.

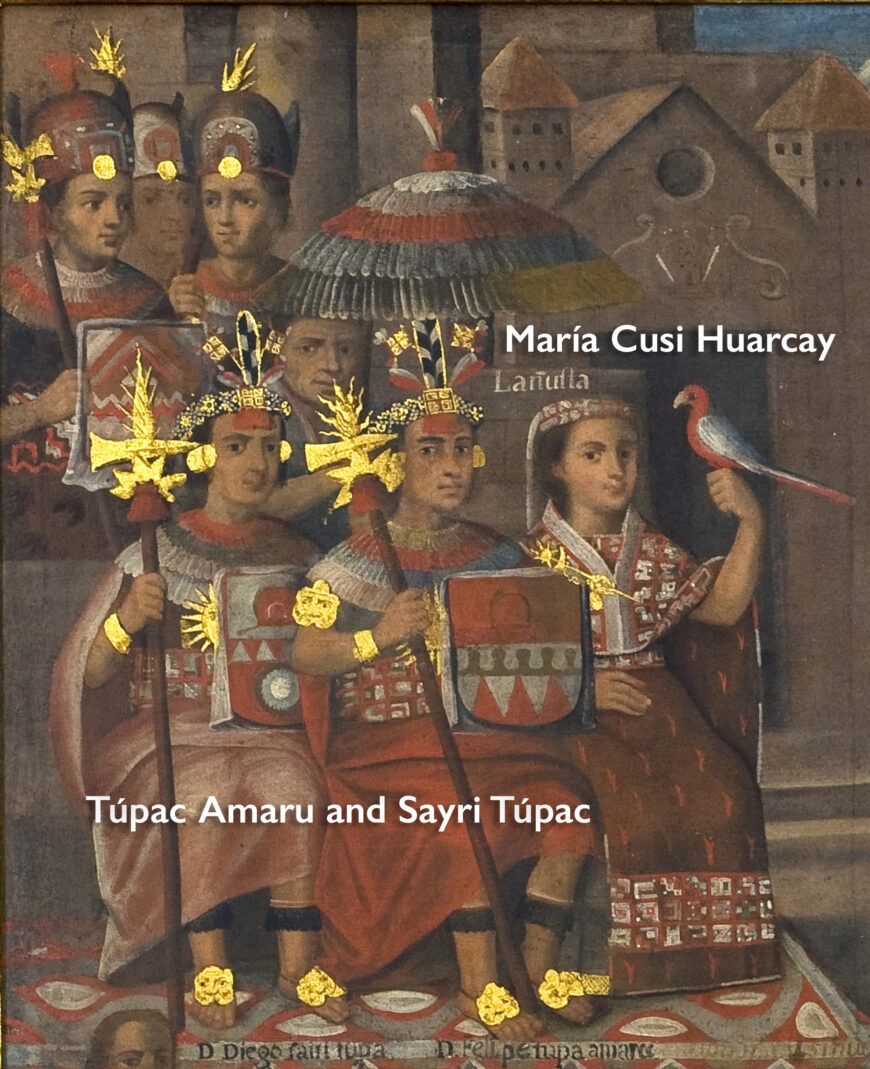

Royalty (detail), Union of the Inka Royal Family with the Houses of Loyola and Borgia, 1718, oil and gold on canvas, 175.2 x 168.3 cm (Museo Pedro de Osma, Lima)

The Inka queen María Cusi Huarcay holds a parrot in the left rear of the painting. Like her daughter Beatriz in the foreground, she wears a dress woven with tucapu geometric designs. Around her shoulder she wears a lliclla shawl that is secured at the chest with a silver tupu pin.

While María Cusi’s garb is entirely Inka in style, Beatriz’s is styled in more of a Spanish fashion, indicating her Inka roots that co-exist in a new Hispanized context alongside her Spanish husband. Indeed he stands between her and the Inka court in the background. Alongside María Cusi sits the Sapa Inka, or king, Sayri Túpac, who ruled over the neo-Inka state housed in Vilcabamba.

Directly next to Sayri Túpac is his more well-known brother Túpac Amaru, who succeeded him to the throne as the final Sapa Inka. Both men wear an elaborate red fringed crown called the mascaypacha, reserved in the prehispanic period for only the Sapa Inka.

This portion of the painting focuses on the trappings of the Indigenous elite, including their clothing, weapons, and the elaborate parasol held over the Sayri Túpac, the Sapa Inka. They all sit before the Jesuit church in Cuzco. The church has a red, white, and black emblem above the doorway which depicts a tower, likely derived from the Habsburg coat of arms. This emblem, a tower pierced by arrows, symbolizes the defeat of the Inka capital of Cuzco by the Spanish, an event which ushered in the new colonial era.

This central message of the painting is further revealed in the language in the cartouche which proclaims “With this marriage, the royal house of the Inka was joined to the houses of Loyola and Borja, whose descendents today are the Marqueses de Alcañices.” The painting celebrates the joining of these families under the Jesuit umbrella as a peaceful and seamless union. The reality was far more grim. The marriage of Beatriz and Martín in the early 17th century was by order of the Peruvian viceroy following the defeat of the Coya’s uncle Túpac Amaru. She was, in effect, a war trophy.

Ana María wearing Spanish-style dress (detail), Union of the Inka Royal Family with the Houses of Loyola and Borgia, 1718, oil and gold on canvas, 175.2 x 168.3 cm (Museo Pedro de Osma, Lima)

By joining an elite Inka family with that of the Loyola family, the Spanish Jesuit enterprise could claim some of the Inka’s royal power, which was seen as necessary for their goal of converting the Andean population. This Jesuit subsumption of Inka power is crystallized in the body of Ana María, the mestiza daughter wearing Spanish-style dress who marries Juan Enríquez in Madrid, an event depicted in the right background of the painting. Ana María maintained an exalted state within colonial society, which was rare for a mestiza. Her link to both the royal Inka bloodline and the Borgia family positioned her in the upper echelons of both Lima and Cuzco society.

For the Inka, the painting also held power for its proclamation, in the largest church in Cuzco (and many other Jesuit churches around Peru), of the continuation of the Inka royal line. Other Indigenous groups such as the Cañari and Chachapoya had been defeated by the Inka before the Spanish conquest and as a result, formed alliances with the Spanish during the conquest and colonial period. By proclaiming the Inka royal line joined to elite Spanish bloodlines, the Inka sought to highlight the continuation of their influence in the region.

The colonial period was fraught with violence and conquest. However, with the clash of cultures emerged something new, and a flourishing of cultural production. The encounter and subsequent development of new traditions, neither entirely Andean nor entirely Spanish, is crystalized in this painting. Here is a visual history that speaks to the multiethnic population and their quest to make sense of the heritage of the past within the new, multiethnic present.