Mexico City side, Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City)

Spices, silks, porcelains and more

François Boucher’s A Bourgeois Breakfast (below) features an upper middle class French family in their fashionable home. In the corner of the room, nestled on a small shelf, is a Buddha statuette, perhaps imported from China, but also possibly created in Meissen, Germany in imitation of Chinese porcelains. “Chinoiserie,” (and later, “Japonisme”) are terms used to describe eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe’s fascination with East Asian goods. In reality Europeans had long sought spices, silks, and porcelains from the East, but the Ottomans controlled the trade in these and other luxury goods.

In search for a direct route to Asia that bypassed Ottoman control, Christopher Columbus, a Genoese navigator backed by the Spanish crown, accidentally stumbled upon the so-called “New World,” though he believed he had found the Western route to Asia. Spanish navigators quickly realized they were not in fact in Asia and set about colonizing the Americas. Europeans soon made their way across the Pacific and the first Spanish settlement in Asia was established in San Miguel, present day Cebu (Philippines) in 1565. The Viceroyalty of New Spain eventually came to include much of North America including Mexico and Central America, as well as the Philippines.

Asia + the Americas (via Spain)

These two disparate Asian and American territories were joined by a fleet of Spanish ships called the Manila Galleon that left biannually from the cities of Manila in the Philippines and Acapulco in Mexico. From Acapulco, Asian luxury goods were transported over land to Veracruz where they were placed onboard ships bound for Spain, or made their way either by boat or mule to port cities like Lima, Havana, Cartagena, and Portobelo.

Elite Spaniards and Creoles decorated their homes and adorned their bodies with stunning examples of East Asian textiles and manufactured goods, as seen in a Mexican portrait of a Young Woman with a Harpsichord (left). The sitter holds an Asian (or Asian-inspired) fan and wears an elaborate silk dress—both the height of fashion at the time. Soon local artists were inspired to create their own versions of Asian goods, or to inject East Asian styles and motifs into their work. The influence of Asian art is particularly evident in viceregal textiles, ceramics, and furniture. Some examples are the resplendent biombos, or folding screens, made in Mexico beginning in the seventeenth century.

Mexico City side, Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City)

What is a Biombo?

The word biombo is a Hispanization of the Japanese byobu, which can be translated as “protection from wind.” The first byobu arrived in Mexico City as early as 1614 and quickly became highly sought after luxury items. These screens, originally imported from China to Japan in the eighth century and made of separate folding panels hinged together, were used within homes to divide or enclose interior spaces. Japanese screens typically featured landscapes with people or animals, but biombo made in Mexico featured secular subjects set within a city or landscape. Popular subjects included Indigenous festivities, allegories of the four continents, and scenes from the conquest of Mexico.

Conquest side, Biombo showing the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City)

Biombo as Map

The Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City in the Museo Franz Mayer in Mexico City (above) is exemplary of the genre. Created in the second half of the seventeenth century, the screen features a panoramic birds-eye map of Mexico City on one side and scenes from the Conquest of Mexico on the other. While both sides of the biombo show the same geographic space (Tenochtitlan/Mexico City), the city is rendered very differently on each side.

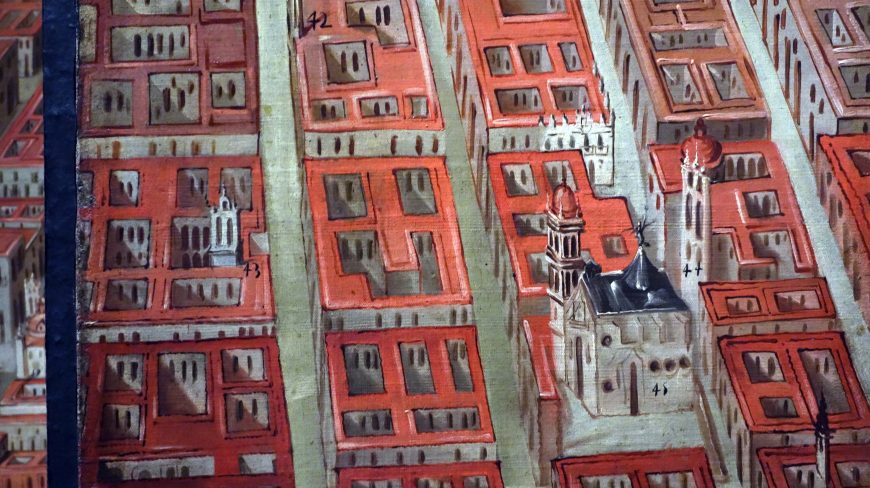

Mexico City streets (detail), Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City)

This birds-eye view of the city (above) gives a cartographic rendering of the city in three dimensions. Likely based on a seventeenth-century map of the city, this side of the biombo focuses on the physical aspects of Mexico City. The image is idealized—privileging the elite Spanish view of the city. Notably absent, for example, are the small Indigenous dwellings that could be found on the outskirts of the city.

Tlatelolco and the landscape beyond (detail), Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City)

Devoid of people, the sweeping city on a lake appears picturesque, with mountains rising in the distance and causeways that radiate out from its carefully organized grid of plaza, streets, and canals. The grid was established by the Mexica (Aztecs) who founded the city. The Spanish troops who arrived in 1519 were amazed; conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote: “Among us there were soldiers who had been in many parts of the world, in Constantinople and all of Italy and Rome. Never had they seen a square that compared so well, so orderly and wide, and so full of people, as that one.”1 He marveled also at the “straight, level causeway,” and “high towers, pyramids, and other buildings, all of masonry, which rose from the water.” For the Spaniards, they had arrived in a city of dreams—one that mirrored the Renaissance ideals of city planning that had yet to be realized in Spanish medieval cities.

Cathedral (detail), Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City)

Following the Conquest, Tenochtitlan was renamed Mexico City, and was transformed to more closely resemble a European city. Painted in one point perspective (a convention of European painting), the biombo showcases seventeenth-century Mexico City as a sprawling metropolis of stucco buildings with red slate roofs. Particular attention is paid to its most prominent structures: churches, schools, hospitals, monasteries, and convents. The perspectival focus is on the traza, the center of the city that was reserved for the Spanish elites, but the Indigenous city of Tlatelolco, the “sister” city of Tenochtitlan, is rendered on the left hand side of the island (above).

Battle scene (detail), Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City)

Biombo as Narrative

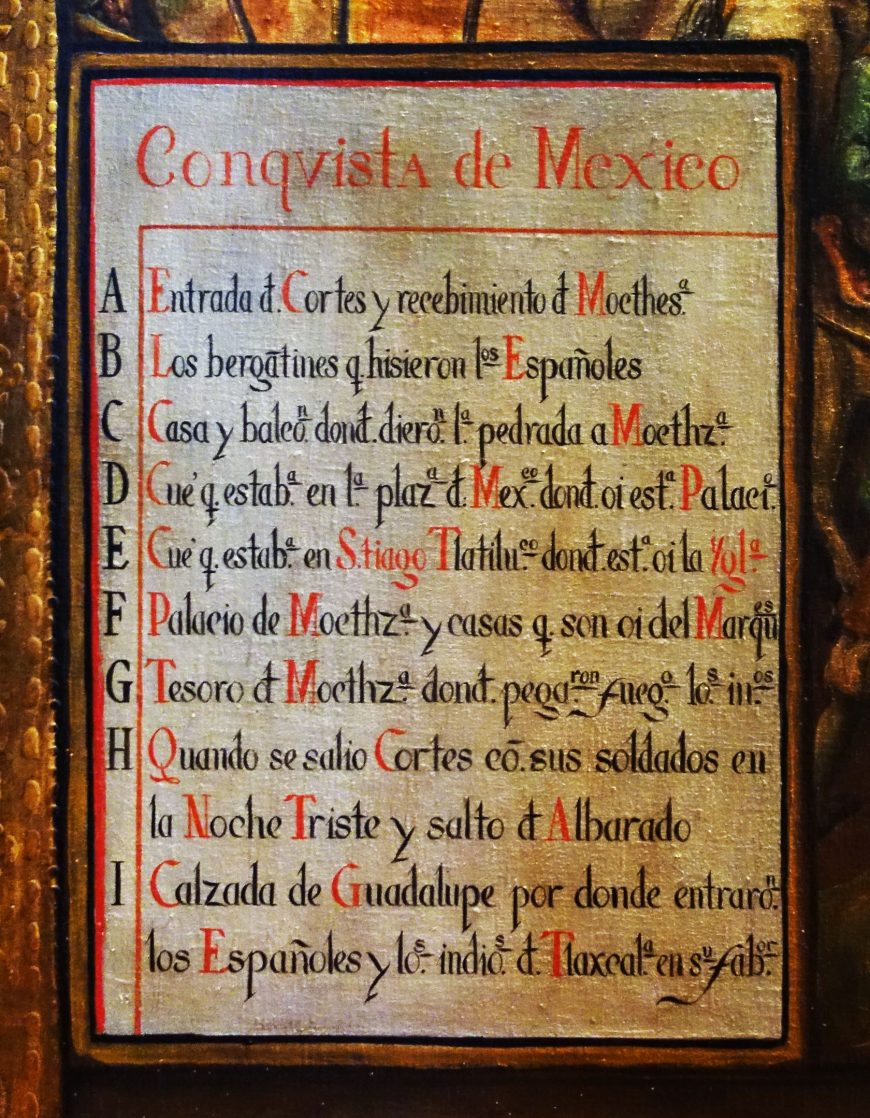

Cartouche (detail), Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City)

Assassination of Moctezuma II (detail), Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City)

Biombo in Context

Imagine this folding screen in a large and sumptuously decorated home in Mexico City. Its recalling of Asian art forms was a reflection of the sophisticated tastes of its cosmopolitan owners. The Spanish or Creole elites would have used the biombo as a conversation piece, or perhaps invented games and riddles that related one episode of the Conquest to a particular part of the city. The biombo could serve as a mnemonic device for recalling collective and oral histories of the city.2 While the Conquest view illustrated the discord of the pre-Hispanic period, the map view celebrated order under Spanish rule. Though never visible at the same time, the two scenes are interrelated, and the act of going back and forth between the physical city and its historic Conquest was one that fascinated both the eye and the mind. Through the act of looking, its owners could superimpose themselves within both the physical and historical city, becoming a part of the transition of the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan to the Spanish capital of Mexico City.

Notes:

1 Bernal Diaz del Castillo, The History of the Conquest of New Spain, ed. John Cohen (New York: Penguin Books Limited, 1963), p. 235.

2 Barbara E. Mundy, “Moteuczoma Reborn: Biombo Paintings and Collective Memory in Colonial Mexico City,” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 45, no. 2/3 (Summer/Autumn 2011), p. 164.

Additional resources:

“The Circulation of Japanese and Mexican Art in the Early Modern World,” Sofia Sanabrais (video)

The Manila Galleon Trade on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America (Fordham University)

Barbara E. Mundy, “Moteuczoma Reborn: Biombo Paintings and Collective Memory in Colonial Mexico City,” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 45, no. 2/3 (Summer/Autumn 2011), pp. 161-176.

Sofia Sanabrais, “From Byobu to Biombo: The Transformation of Japanese Folding Screen in Colonial Mexico,”Art History 38, 4 (September 2015), pp. 778-791.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”FMBiombo,”]