Introduction to Andean Cultures: From textiles to ceramics, metalwork, and architecture, Andean cultures produced art and architecture that responded to their natural environment and reflected their beliefs and social structures.

Read Now >Chapter

The colonial Andes and the Viceroyalty of Peru

When we study colonialism, we imagine a hierarchical and rigid society, based on the occupation of territories, the exploitation of nature, and of Indigenous people. The centuries-long colonization of the Americas is often presented as a unit that ends with the independence movements of the 18th and 19th centuries. In reality, the centuries of European colonization in the Americas were a slow process of establishing and maintaining control: a process that shifted, changed, and adapted to each specific territory.

The boundaries of the Spanish viceroyalty of Peru in around 1542 (created for the exhibition “Tesoros/Treasures/Tesouros: The Arts in Latin America, 1492–1820,” Philadelphia Museum of Art © 2006 Anandaroop Roy)

Despite being established as an administrative unit, the territories of the Viceroyalty of Peru (whose borders changed several times throughout the colonial centuries) encompassed various geographical and cultural units, with diverse worldviews that resulted in different responses to colonial occupation. At the same time, Spaniards from varied social positions, other Europeans, alongside enslaved Africans, all brought their own particular perspectives to the occupied Andes, where many different Indigenous peoples had lived for millennia.

Between 1542, ten years after Francisco Pizarro’s arrival at the port of El Callao, in present-day Peru, until the 1820s when the Spanish were ousted, the Viceroyalty of Peru expanded, contracted, and changed. At the same time, Indigenous people living in the Andes created cities, traditions, technologies, networks of trade, and cultural exchanges that, although truncated by the violent European invasion, continued, adapted, resisted, and shaped Peru throughout the colonial centuries, its independence, and right up until the present-day. In this chapter we will focus on how the visual culture of the Andes allows us to see some of these changes as well as challenges the notion of the Viceroyalty as a narrowly defined political and cultural driver.

Read about the Andes and the Viceroyalty of Peru

Introduction to the Viceroyalty of Peru: The Spanish conquest of the Inka Empire brought about fundamental changes to the Andean social, political, and cultural landscape.

Read Now >/2 Completed

Colonialism and the codification of space

One of the main goals of colonization is the occupation and exploitation of land. But at the same time, how space was thought of and described is often one of the last things we think about when studying colonial centuries.

When the Europeans became aware of the existence of the lands that would be named the Americas, their conception of the world changed. The Americas de-stabilized not only the pre-existing knowledge about the physical world, but also the place of Europe within it. At the same time that navigation tools were being perfected, the ways of representing the world were changing.

In this process, the ways that space was depicted, mostly in maps, became a central tool to understand this world altering moment, and the expanding power of European monarchies created a sense of heightened relevance for cartographic depictions of newly-accessed worlds. European conceptions of space, however, now needed to coexist with the multiplicity of understandings and definitions of space and territories present in the Andes.

The modern city of Cuzco (photo: Tryphon, CC BY-SA 3.0)

One of the most explicit ways in which this tension between the different systems for thinking about and representing space is visible in the city of Cuzco, in present-day Peru. The capital of the Inka empire, a highland city located at an elevation of 11,152 feet, Cuzco functioned in many ways as a second capital for the Viceroyalty, centering many of the most important enterprises of the Spanish colonial government. Part of the importance of Cuzco was its status as the capital of the Inka empire (Tawantinsuyo), the geographical organization of the Andes according to the Inka, and the many Andean cultures connected to them.

Foreground, Ruins of the Qorikancha (the Convent of Santo Domingo above), Cuzco, Peru (photo: Terry Feuerborn, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Some of those colonial-era initiatives are visible in the very layout of the architecture of the city, since the Spanish built directly on top of the Inka’s pre-existing spatial organization. For example, the open area of the city, which was used by the previous Indigenous cultures for ritual purposes, became the Spanish Plaza de Armas where the main temple of Christianity (the cathedral) was located. The Inka palace or Qorikancha became the church of Santo Domingo, another example among many strategies employed by the Spaniards to resignify space as part of their project of colonization.

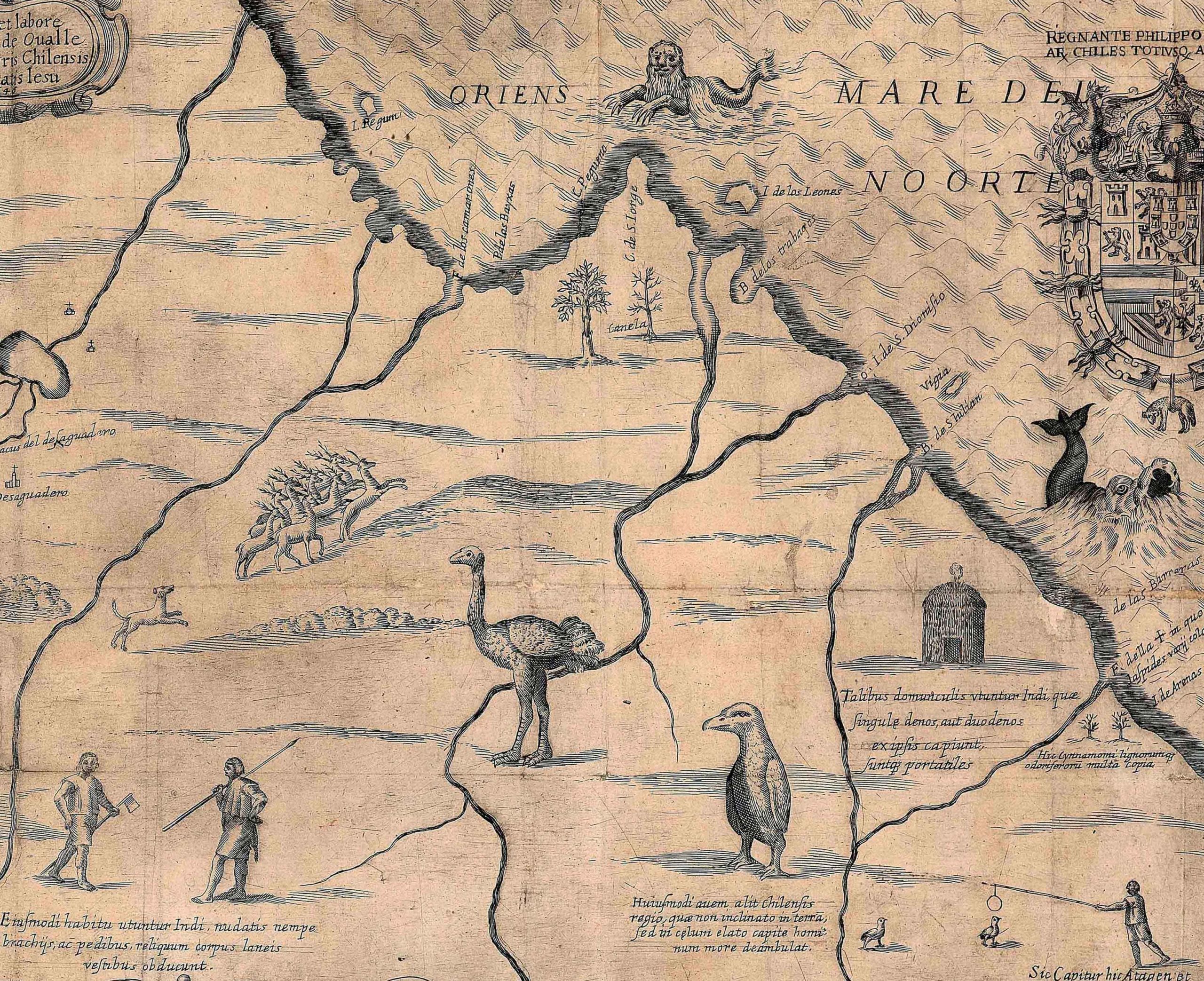

Alonso de Ovalle, Tabula geographica regni Chile, 1646 (John Carter Brown Library, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island)

As a way to encourage the European settlement of more distant areas of the Viceroyalty, visual depictions, such as maps, were used to describe the possibilities inherent in the “new” lands depicted. This is the case of Alonso de Ovalle’s 17th-century Tabula Geographica, which depicts the Reino de Chile, the southernmost area of the Viceroyalty of Peru, as a land of wonders, exotic animals, adventure, and opportunity.

Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of the Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí, 1716, oil on canvas, 240 x 570 cm (Museo de América, Madrid)

Depictions of space were also used to display the prosperity of the new colonies, and especially to describe American cities as part of the Spanish world. This is the case of the 18th-century painting by Melchor Pérez de Holguín depicting the entry of the viceroy into the city of Potosí; displaying the celebration as a confirmation of the participation of the city of Potosí in the colonial enterprise.

In each of these depictions, fact and myth are intertwined. The goal is not only to describe space as a way to entice or confirm the Spanish occupation, but also to construct an ideal image of the colonies—an image that nevertheless changed depending on the position and status of each territory within the colonial administration.

Read essays about colonialism and the codification of space

City of Cuzco: The city of Cusco was not just the capital of the Inka empire, it was an axis mundi—the center of existence—and a reflection of Inka power.

Read Now >

Alonso de Ovalle, Tabula geographica regni Chile: This is one of the earliest maps of Chile that was disseminated in Europe.

Read Now >

Melchor Pérez de Holguín, Entry of the Viceroy Archbishop Morcillo into Potosí: The artist represents the triumphal entry of the Viceroy Archbishop Diego Morcillo Rubio de Auñón, who was a colonial official and bishop in the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Read Now >/3 Completed

The religious image: ideology of colonization

One of the main justifications for the Spanish colonial occupation of the Americas was the evangelization of the Indigenous people that inhabited it. Since the arrival of Columbus to the islands of the Bahamas, the conversion of souls to Christendom was used as a rationale for invasion. Just two years after Columbus arrived, the Treaty of Tordesillas divided the Americas between Spain and Portugal and the global supremacy alleged by the papacy was used as a justification for the claim that the European monarchs were the rightful “owners” of the territories of the Americas.

Importantly, at the very moment that Spain was occupying the Americas using Christianity as a driving motivation, the Catholic church was re-examining its central tenets in the face of the Protestant Reformation. In this context, religious images, much questioned by Protestants, gained a renewed primacy for Catholicism, and their use was in fact expanded in response to the millions of potential new believers in the Americas.

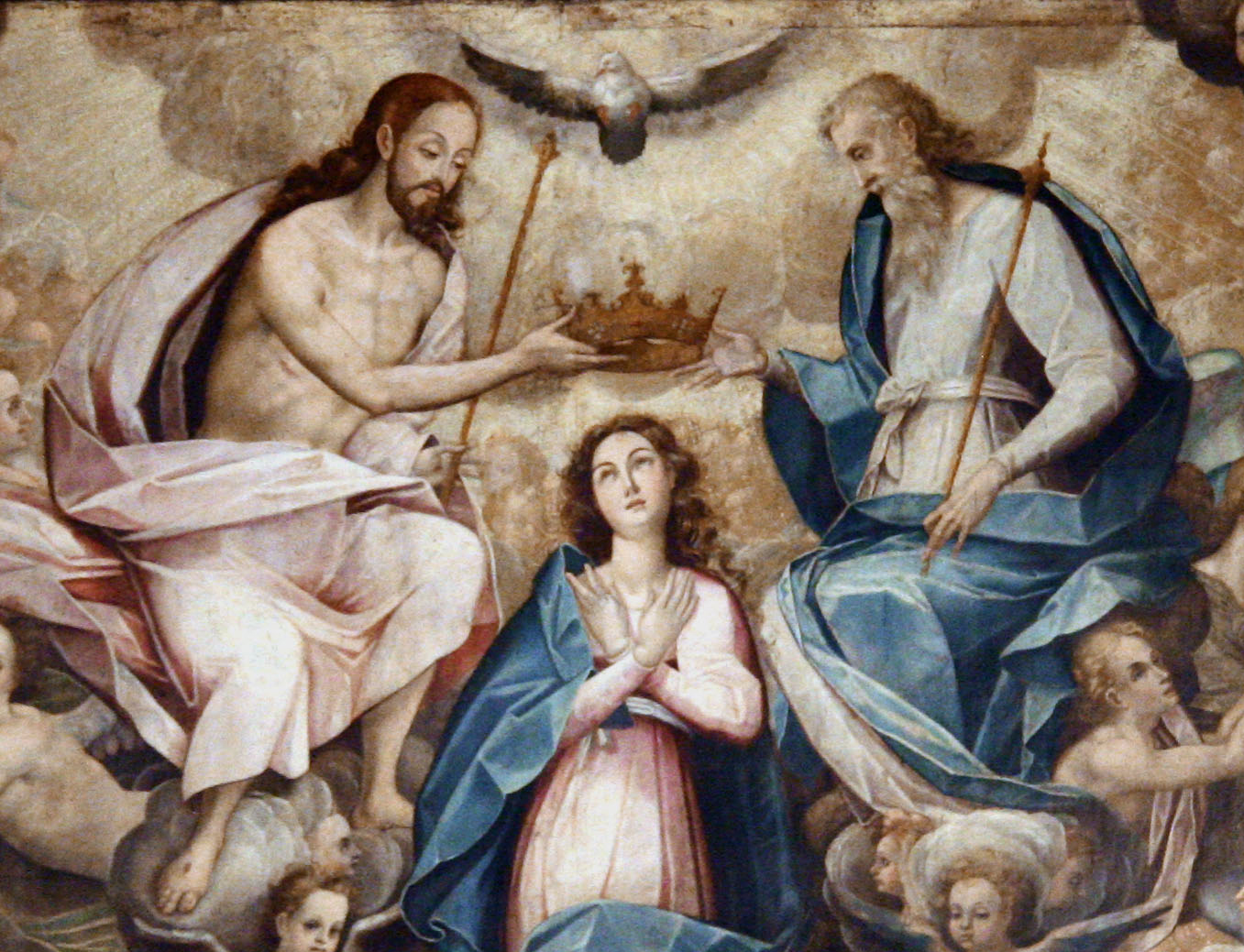

Bernardo Bitti, Coronation of the Virgin, 1575–80, Church of San Pedro, Lima, Peru, tempera (public domain)

For this reason, the creation and distribution of images depicting the stories of the Catholic faith was a central aspect of the colonizing project. During the early years of the occupation, Italian artists were brought to the Americas with the expressed purpose of producing appropriate religious images for the new temples of the Viceroyalty. Bernardo Bitti was one of those Italian painters, and his influence was fundamental for the pictorial production of the following centuries in the viceroyalty. One of his works, the Coronation of the Virgin, depicts in an Italian style one of the main narratives connected to the Counter-Reformation—the promotion of the figure of the Virgin Mary.

Gregorio Vasquez de Arce y Ceballos, Symbol of the Trinity, 17th century (Colonial Museum, Bogotá)

The need to explain and establish the basic tenets of the Catholic faith in the colonies created a predilection for motifs that were not as widespread in Europe. For example, the trifacial trinity (the depiction of the holy trinity as three identical men) was a specific motif that was banned in Europe in the 17th century but continued vigorously in the viceroyalty of Peru well into the 18th century.

The Child Mary Spinning, 18th century, oil on canvas, Cuzco, Peru, 36 x 28 inches (Collection of Carl & Marilynn Thoma)

Another example of a specific iconography that was used in the viceroyalty of Peru, but was not popular in any of the other colonies in the Americas, was the Virgin Mary as a child spinning, a scene of the life of the Virgin taken from apocryphal texts. One of the hypotheses of why this specific aspect of the Virgin was so popular in the viceroyalty of Peru was the importance of textiles in the Andes. In this way, perhaps pre-conquest values informed a sacred Catholic image for an Indigenous audience.

In the 18th century, a particular archangel iconography gained popularity throughout the Andean region: the archangels with arquebus. These series of seven or more archangels took a known European motif of depicting celestial figures as warriors and updated them, both in the clothing and weaponry of the European colonizers. This was a way to further the goals of evangelization while also deepening the population’s connection to colonial occupation.

Read essays and watch videos about religious images and the ideology of colonization

Introduction to religious art and architecture in early colonial Peru: The transmission of Christianity to the Andes was both an ideological and artistic endeavor.

Read Now >

Bernardo Bitti, Coronation of the Virgin: Bitti was one of many artists who made the journey across the Atlantic in this period as part of the Spanish Crown’s effort to colonize and evangelize the Indigenous populations.

Read Now >

The Coronation of the Virgin by the Holy Trinity: We often find paintings of Mary in convents, where she served as an example to the young women who came in as novices and spent their days, like Mary, in seclusion, praying, reading, and creating elaborate textiles for the church.

Read Now >

The Child Mary Spinning: There’s a long and rich history of textile traditions in the Andes that continued through the Inka period, and some of the elements in Mary’s costume might relate to, or be interpreted by Indigenous viewers as relating to that tradition.

Read Now >

Master of Calamarca, Angel with Arquebus: Representing celestial, aristocratic, and military beings all at once, these angels were created as Christian missionary orders persistently sought to terminate the practice of pre-Hispanic religions and enforce Catholicism.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Indigenous artists: materiality and agency

The growing need for the production of images in the colonial Andes was satisfied in part by the participation of several Indigenous artists and highly skilled crafts people. The use of Indigenous knowledge and skill in painting and weaving during the colonial centuries demonstrated how both in the pre- and post-conquest Andes, artists were recognized as important members of society. This may also explain why many members of the Indigenous elites dedicated themselves to the creation and construction of works of art. Participating in the visual arts waived certain rules otherwise required of Indigenous people by the Spaniards, including most importantly, mita: the participation in the forced labor system overseen by the Viceroy Toledo, the main architect of the colonial legal system in the viceroyalty.

Because of the long tradition of image-making in the Andes before the European invasion and the importance of images for the Christian society of the colonial Andes, Indigenous patrons also commissioned works by Indigenous artists. High ranking Indigenous families placed their sons and grandsons in artist’s workshops as apprentices, resulting in a vibrant system of Indigenous art making that existed despite the limitations of colonial society. It is within this context that what has been identified as the first Indigenous school of painting of the colonial Americas appears: the Escuela Cuzqueña or Cuzquenian School.

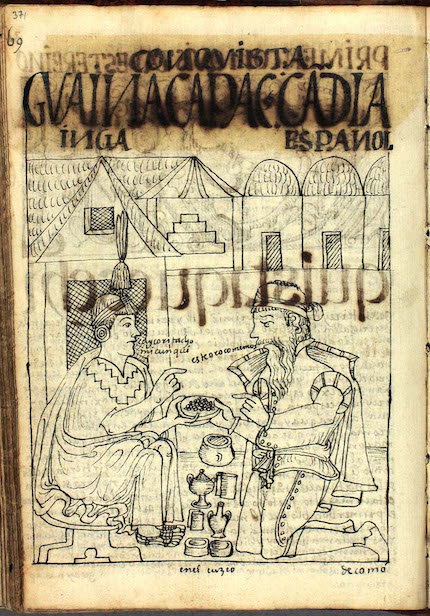

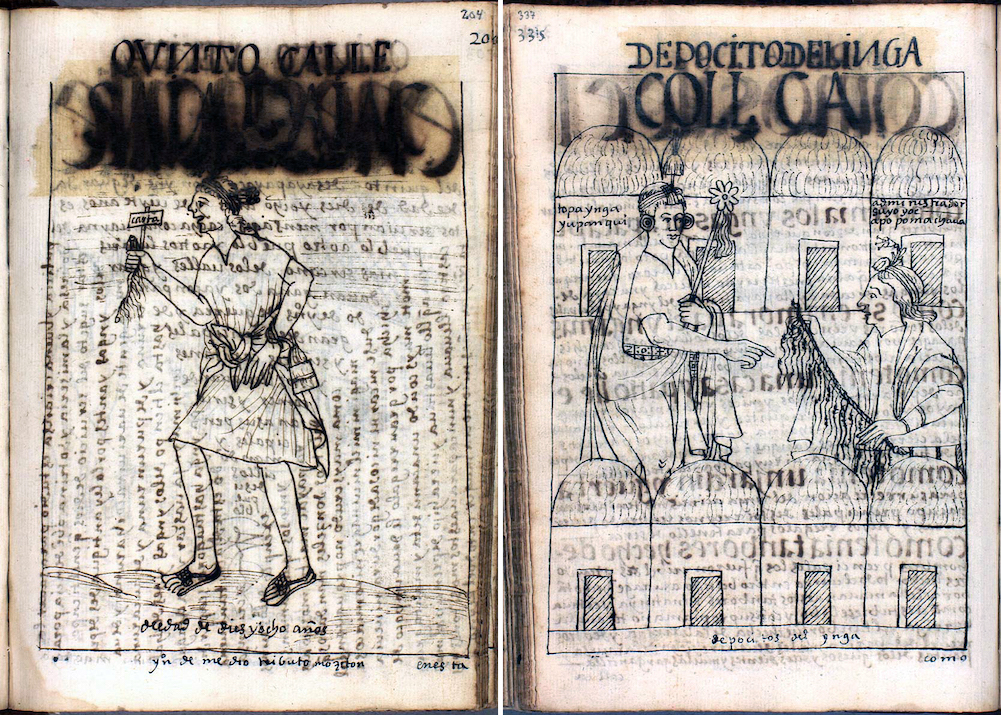

The Inka asks what the Spaniard eats. The Spaniard replies: “Gold.” From Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, The First New Chronicle and Good Government (El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno), c. 1615 (The Royal Danish Library, Copenhagen)

Cuzquenian painters were not the only ones using their craft as a way to secure their place in colonial society. Most prominently Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, an Indigenous artist and intellectual from the area of Ayacucho, in present day Peru, famously worked with Spanish priest Martin de Murua, and later created a twelve-hundred-page letter addressed to the king of Spain retelling the history of the Inkas and the atrocities committed by the Spaniards. Guaman Poma used both writing and drawings (there are more than 390 illustrations) to tell this story. He used both European conventions and Indigenous traditions to convey his message and identified himself as an author and artist on several pages of the manuscript. Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala exemplifies the role of Indigenous artists in the colonial Andean society.

Indigenous people participated in the production of visual objects in the colonial Andes. Workshops of Indigenous painters, sculptors, architects, and silversmiths proliferated in cities like Cuzco, Lima, Potosí, and Santiago. They owned and led workshops, and at the same time indios de la calle or common Indigenous people would participate informally in workshops led by Indigenous masters and Europeans alike. Each group brought specific meaning to the images being produced, as well as particular approaches to the multiplicity of audiences encountering their works. Particularly interesting are the mural paintings done in rural churches throughout the Andes that focused on evangelization while also providing space for Indigenous communities to continue their traditions, although in a covert manner.

Learn more about Indigenous artists: materiality and agency

Textiles in the Colonial Andes: Textiles and their creation had been highly important in the Andes long before the Inka came to power in the mid-15th century.

Read Now >

Keru Vessel: Over the years, the Spaniards realized that the kerus were not simple cups, but meaningful objects that continued to be used in Andean rituals.

Read Now >

Cuzco School Artist, Saint Joseph and the Christ Child: While Inkan and Euro-Christian styles may seem like two very distinct “visual languages,” Saint Joseph and the Christ Child reminds us that many colonial viewers could have been fluent in both.

Read Now >

Guaman Poma and The First New Chronicle and Good Government: Guaman Poma’s discussion of Inka culture provides us with information that would otherwise be lost to us.

Read Now >

The Paths to Heaven and Hell, Church of San Pedro de Andahuaylillas: Filled with canvas paintings, statues, and an extensive mural program, the level of artistry afforded to this church rivals its counterparts in Renaissance Italy.

Read Now >

Our Lady of Cocharcas and the Cuzco School of Painting: The Cuzco School developed a unique style characterized by a bright color palette, flattened forms, Indigenous symbolism, and a profusion of gold ornament.

Read Now >/6 Completed

Navigating the colonial context: identity and status

Images in the colonial Andes were used to reinforce, construct, and record social, political, and religious roles and norms. The representation of one’s place in the world, or the place of others, became important topics within Andean painting, and they allow us to see, centuries later, how the people of the Andes represented themselves and their context during the colonial period.

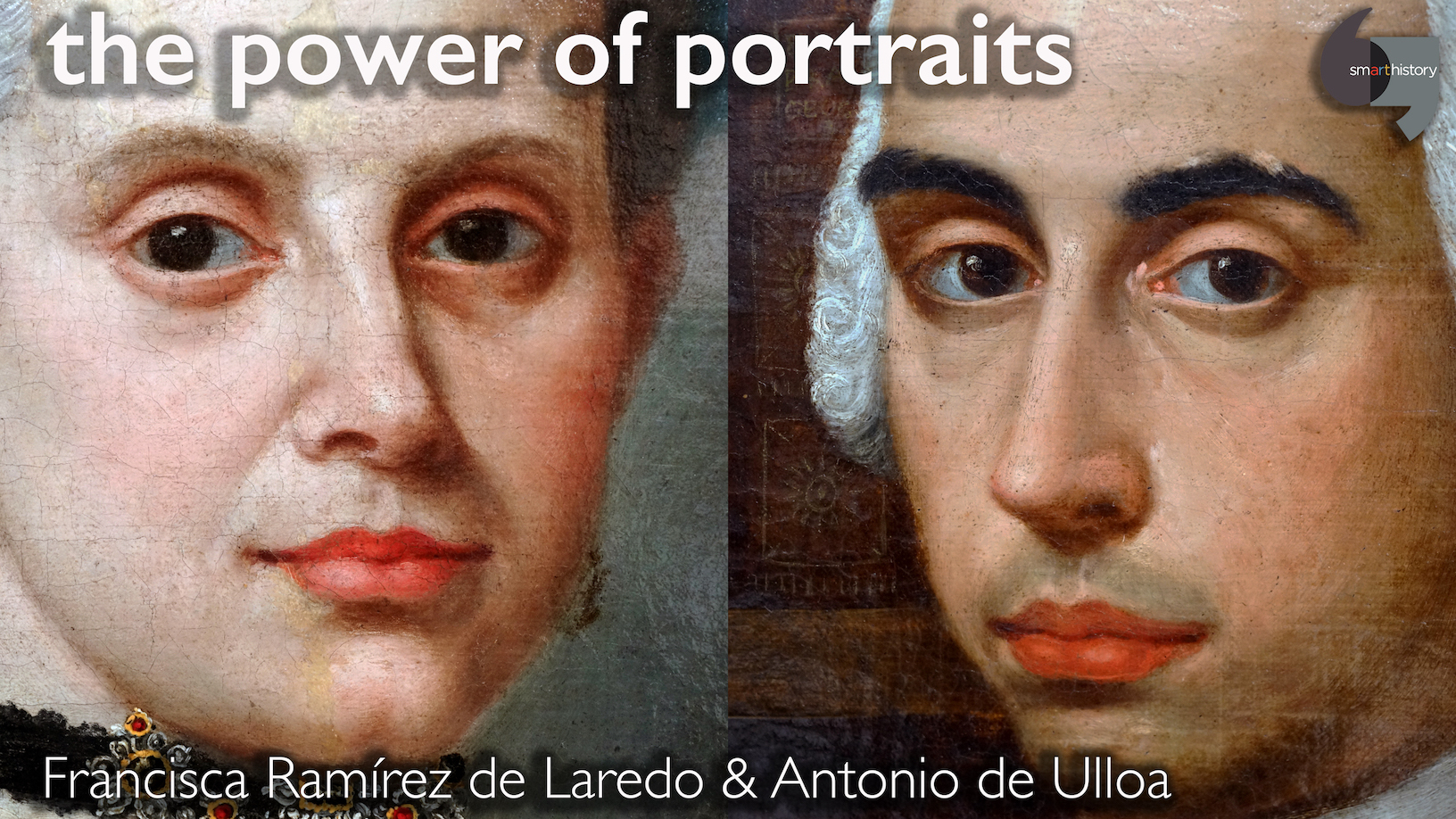

Portraiture was a tool for reinforcing and constructing power. Viceroys, bishops, and other members of the elite hung their likeness in important buildings. These portraits mirror European ideas of status and representation but in an Andean context.

Paintings depicting parades and other public celebrations of colonial Peru are similarly revealing. The series of Corpus Christi, for example, shows an idealized image of colonial society: how the social order and relationships between different members of society were supposed to interact and organize around the Christian ritual calendar or other ceremonies connected to the colonial apparatus.

These are pictorial spaces for the construction of identity (public spaces, portraits, and donors in religious paintings) mostly by and for the elites. Through careful examination, we can see how people in different groups of the Andean colonial world navigated this shifting society.

These depictions of power and identity re-gained popularity in the 18th and 19th century when criollos asserted their status, an expression of political power that eventually led to the independence for the countries of the region. Portraiture in particular continued to be a favored genre in the newly independent nation-states and continued to construct identity and to reinforce power into the modern era.

Read essays and watch videos about identity and status in the colonial context

Portrait Painting in the Viceroyalty of Peru: Portraiture was an important artistic genre for wealthy elites to assert power and legitimacy in the Viceroyalty of Peru.

Read Now >

Parish of San Sebastián, Procession of Corpus Christi series: Inka, Spanish, and Christian traditions come together in this 17th-century painting of a religious procession in Cuzco (in present day Peru).

Read Now >

Official Portrait of Bishop Luis Francisco Romero: Did the official portraits produced in the Viceroyalty of Peru really convey the wealth of the sitter?

Read Now >

Portraits of Francisca Ramírez de Laredo and Antonio de Ulloa: Official religious portraiture in the Viceroyalty of Peru drew on a visual vocabulary inherited from Spanish portraiture traditions and formalized in workshops at Lima.

Read Now >

Portrait of Don Marcos Chiguan Topa: Don Marcos claimed to be descended from the first Inkas to convert to Christianity due to the missionizing efforts of the Spanish. This was a strategic move.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Key questions to guide your reading

How does art reflect some of the changes in the structure and form of the viceroyalty of Peru?

In what ways did the art and visual culture reflect the goals and aims of European colonialism in the viceroyalty of Peru?

What are some of the different places where we can see the agency and presence of Indigenous people within the colonial centuries?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow does art reflect some of the changes in the structure and form of the viceroyalty of Peru?

In what ways did the art and visual culture reflect the goals and aims of European colonialism in the viceroyalty of Peru?

What are some of the different places where we can see the agency and presence of Indigenous people within the colonial centuries?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Andes

Colonialism

Viceroyalty

Inka

Tawantinsuyo

Evangelization

Treaty of Tordesillas