John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere, 1768, oil on canvas, 89.22 x 72.39 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The fame of Paul Revere

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April in Seventy-Five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

He said to his friend, –“If the British march

By land or sea from the town to-night,

Hang a lantern aloft in the belfry-arch

Of the North-Church-tower, as a signal-light—

One if by land and two if by sea;

And I on the opposite shore will be,

Ready to ride and spread the alarm

Through every Middlesex village and farm,

For the country-folk to be up and to arm.

—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Thus begins Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem “Paul Revere’s Ride,” a work that was first published in the January 1861 issue of The Atlantic Monthly. Although Paul Revere is now famous as one of the Massachusetts Minutemen—a local militia who would defend the colony against the British army at a moment’s notice—he was hardly a public figure during his own lifetime. History tells us that he did ride from Boston’s Old North Church to warn of the approach of the British, but he was never elected to public office and he was only tangentially involved with Revolutionary politics. Indeed, Revere’s limited fame in his own day stems from his considerable talents as a silversmith. His fame during the second half of the nineteenth century comes from his appearance in Longfellow’s poem. Revere’s fame today, however, can be attributed—in part at least—to the remarkable portrait John Singleton Copley painted of the artisan in 1768.

Copley’s beginnings

Copley had extensive access to early eighteenth century prints, and he often incorporated poses and clothing from older images into his portraits of Bostonians (his mother married Peter Pelham, an engraver who specialized in mezzotints after his father died). At the age of 15, for example, Copley painted the portrait of Mrs. Joseph Mann (Bethia Torrey). Her pose—holding a sting of pearls—and attire of a scoop-neckline dress with white trim—were directly taken from a mezzotint of Princess Anne. In today’s world, we might look at such “borrowing” as a kind of visual plagiarism. But this was the vein in which eighteenth-century artists worked and learned. It was expected that one could become great through the attentive copying of the Old Masters.

Left: Queen Anne when Princess of Denmark by Isaac Beckett, after William Wissing, mezzotint, 1683-1688, 32.6 x 25 cm (National Portrait Gallery, London); right: John Singleton Copley, Mrs. Joseph Mann (Bethia Torrey), 1753, oil on canvas, 91.44 x 71.75 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

John Singleton Copley, A Boy with a Flying Squirrel (Henry Pelham), 1765, oil on canvas, 77.15 x 63.82 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

As Copley matured as an artist, however, he became more compositionally inventive. A great example of this is an early masterpiece, Boy with a Squirrel, a portrait of the artist’s half-brother, Henry Pelham. Copley sent this portrait to London for the 1766 exhibition of the Society of Artists. Copley received feedback from his contemporary expatriate Benjamin West and Sir Joshua Reynolds—perhaps the most authoritative voice on British art at the time. Captain R.G. Bruce, Copley’s friend, took Boy with a Squirrel to London and returned with Reynolds’s assessment: “in any Collection of Painting it will pass for an excellent Picture, but considering the Disadvantages…you had labored under, that it was a very wonderfull Performance.” The “disadvantages” to which Reynolds refers to are likely those that involve Copley’s location (Boston, the very fringe of the British empire) and his opportunity for formal artistic instruction there (none).

John Singleton Copley, John Hancock, 1765, oil on canvas, 124.8 x 100 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

And yet despite these disadvantages (although some scholars of American art believe that it was because of them), Copley quickly became the most sought after portrait painter in the colonies. By the middle of the 1760s, he was painting the economic and political elite of his city, and had become a rather wealthy man himself. Before the 1760s were done, Copley had married into a wealthy family and had purchased a 20-acre farm with three houses on it. This estate placed Copley next door to John Hancock, one of the wealthiest merchants in Boston (and future president of the Continental Congress and governor of Massachusetts) when Copley painted him in 1765 (left).

But it was not only the wealthy and political elite who Copley painted. Indeed, during a politically tumultuous time, Copley painted both sides of this vitriolic divide, both Whigs (those in favor of a break with Great Britain) and Tories (those who wished to remain a part of the Empire).

It seems that Copley’s only requisite was that the sitter had the finances to pay for the likeness. It is also possible that Copley would paint a sitter for exchange for past or future goods or services. Paul Revere, a silversmith with modest if not affluent means, might just be one such case.

The portrait of Paul Revere

Copley’s portrait of Paul Revere is striking in many ways. To begin, Revere sits behind a high polished wooden table. Rather than wear his “Sunday’s Best” clothing, as sitters for portraits (and elementary school pictures) so commonly did (and still do), Revere instead wears simple working attire, a decision that underscores his artisan, middle-class status. His open collared shirt is made from plain white linen, and the lack of cravat—a kind of formal neckwear—lends to the informal nature of the portrait. What looks to be an undershirt peeks from underneath his linen shirt, and a wool (or perhaps a dull silk) waistcoat is likewise unbuttoned (although decorated with two gold buttons, features that were not likely present in Revere’s work vest). He does not wear a jacket or coat, and even his wig—something almost every male would have worn if they could to afford to do so—is missing. We can compare what Revere wears to men’s attire from the twenty-first century. Imagine a man wearing a three-piece suit (blazer, vest, buttoned white dress shirt, and a tie). If you were to remove the jacket and tie and unbutton the shirt and vest, you would have an idea of the informality present in Copley’s eighteenth-century portrait of Revere.

John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere, 1768, oil on canvas, 89.22 x 72.39 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

Indeed, comparing Copley’s portrait of the silversmith with that of Copley’s neighbor, John Hancock, makes the differences all the more obvious. Both seem to be at work in some ways—Revere on his teapot and Hancock at his ledger—but there the similarities end. Even though Hancock is not dressed as ostentatiously as he could have been, he still wears a dark blue coat that is embellished and trimmed with golden braid and buttons. White cuffs extend beyond his sleeves, and a silken cravat is tied around his neck. His breeches have golden buckles and silk stockings cover his lower legs. A modest powered wig sits upon his head. This modest attire—modest for Hancock, at least—demonstrates the uniqueness of Copley painting Revere while wearing what amounts to working clothes. Indeed, this is the only completed portrait Copley painted of an artisan wearing less than formal attire.

Face (detail), John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere, 1768, oil on canvas, 89.22 x 72.39 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

But it is not only what Revere is wearing, it is also what he is doing. The sitter looks at the viewer, as if we have momentarily distracted him from his work. The edge of the table in the foreground suggests that the table he sits behind is parallel to the picture plane. Few would claim that this table is his workbench, for the surface is far too polished and pristine to have been used in the daily activity of his trade. The surface of the table reflects Revere’s white shirt, and the tools in front of him, his engraver’s burins. With his right hand, Revere seems to support his head—and as a corollary, his brain—the source of his artistic ingenuity. His left hand holds the product of that mind, a nearly completed silver teapot, a vessel that has been polished to such a high sheen that Revere’s hand beautifully reflects on its surface.

Tabletop and teapot (detail), John Singleton Copley, Paul Revere, 1768, oil on canvas, 89.22 x 72.39 cm (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

As a silversmith, Revere made many kinds of objects; spoons, bowls, shoe buckles, dentistry tools, beer tankards, creamers, coffee pots, and sugar tongs. That he should be shown with a teapot was an overtly political decision. By the end of the 1760s, Great Britain was nearing financial ruin after the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War (the North American component of this conflict is called the French and Indian War; the most famous depiction of this war is Benjamin West’s 1770 painting The Death of General Wolfe). In order to increase the revenue in the crown’s coffers in 1767 the British Parliament passed the Townshend Acts, which placed a tax on the colonials’ use of tea (among other imported goods). Paul Revere was clearly engaged in this political issue, for his signature appears on an October 1767 Non-importation agreement. Clearly tea was becoming a politicizing good and it is interesting that Revere chose to be shown holding an object so tied to a commodity that became a divisive symbol. Indeed, this political thread reached a climax with the so-called Boston Tea Party on 16 December 1773 when a collection of colonials—some disguised as Native Americas—raided a merchant vessel in Boston Harbor and threw the tea overboard. Interestingly, the owner of that boat was Richard Clarke, John Singleton Copley’s father-in-law.

Copley, Revere and the Boston Massacre

One other facet of the portrait of Paul Revere is worth exploring, that of its date of completion, for the artist seldom dated or signed his portraits. Copley and Revere had been acquainted since at least 1763 when Revere’s account book notes that Copley had ordered a gold bracelet. Revere also subsequently made sliver frames for Copley’s miniature portraits, and it has been suggested that this portrait might have served as a kind of payment from Copley to Revere for past services rendered and goods received. Clearly, Revere and Copley had a professional relationship. However, this relationship did not likely extend beyond the first half of 1770.

One of the most pivotal movements leading up to the American Revolutionary War was the so-called Boston Massacre. On 5 March 1770, a group of British soldiers fired at an unarmed group of protesters who were throwing snowballs (loaded with rocks) and other objects at the infantrymen. The crowd also repeatedly yelled “Fire!” at Captain Preston, the commanding officer on duty, daring him to order his soldiers to fire their muskets into the crowd. Eventually, the British army obliged their tormentors; five men were mortally wounded and another six were wounded. The soldiers were arrested and stood trial, accused of murder. Their lawyer was future President John Adams, achieved six acquittals and two reduced charges of manslaughter.

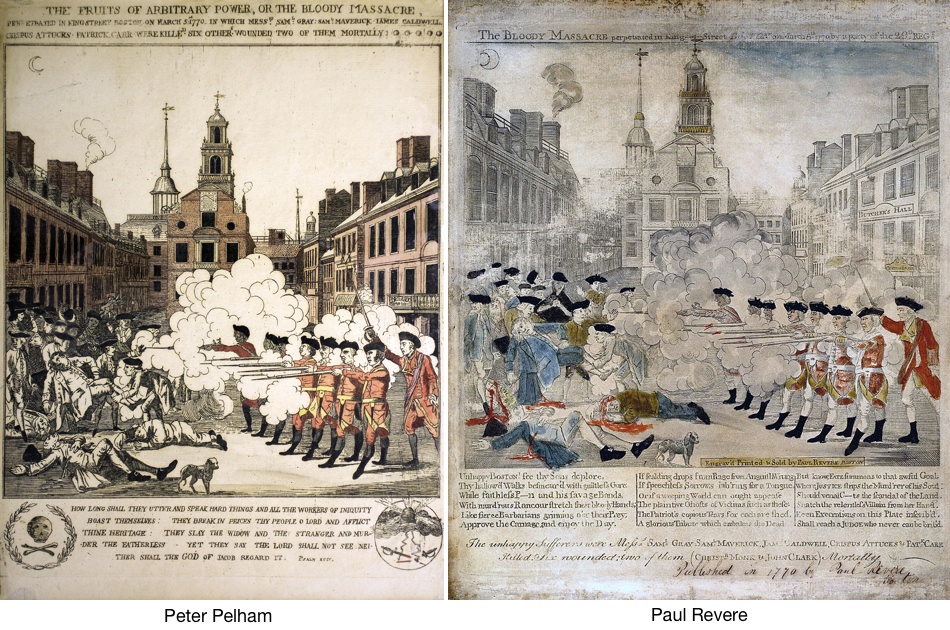

This event was instantly politically divisive, and both Whigs and Tories began to use visual propaganda as a way to bring those who were neutral in regards to declaring independence from Great Britain onto their side. In short time, Henry Pelham, Copley’s half-brother completed one such attempt at depicting the events of the Boston Massacre. Pelham finished his engraving immediately following the events of 5 March and then lent a copy to Paul Revere. The silversmith, who had been engraving political cartoons since at least 1765, and ever the entrepreneur, then faithfully copied Pelham’s print and placed an advertisement for its sale no later than 26 March, just three weeks after the event and a week prior to Pelham’s own print being available for purchase.

Left: Henry Pelham, Boston Massacre; right: Paul Revere, Boston Massacre

When seen side by side, it is clear that Revere plagiarized Pelham’s then unpublished work; the same arrangement of dead and injured bodies on the left, the same organization of the British soldiers on right, the same dog, the same framing architecture. Although the crescent moon is placed in the same part of the print—the upper left-hand corner—the biggest difference between these two images could be that Pelham’s moon is open on its right side whereas Revere’s is open to the left. This egregious affront against a family member likely brought an end to John Singleton Copley’s relationship with Paul Revere.

It is ironic that Revere is most known today because of Longfellow’s poem, a work that does not mention his more famous artisanal career. Copley’s portrait of the silversmith, likewise as famous, was hidden in a descendant’s attic for most of the nineteenth century and was not publicly displayed until 1928. Since that time, however, the image has contributed to the sitter’s prestige, and the sitter’s fame has likewise contributed to the painting’s fame.