A secret faith

In 1596, Luis de Carvajal, along with his mother and sisters, were condemned to the flames of an auto da fé in Mexico City for their secret adherence to Judaism. The Carvajals were conversos, descendants of Jews who converted to Catholicism often under great duress in Spain and Portugal during the late middle ages. A minority of these converts maintained their ancestral faith in secret, braving the wrath of the Inquisition.

The Carvajals moved to Mexico for the same reason other Spaniards left the Old World for the New—economic opportunities and the chance to remake themselves in a new land. While the Inquisition only functioned in the Americas beginning in 1571, many conversos migrated to the ports and major urban centers of the Americas from the earliest days of Spanish conquest and colonization in the early 16th century. Carvajal’s uncle, also named Luis de Carvajal, was a decorated conquistador who was named the governor of the frontier territory of the Nuevo Reino de León in the Northeastern part of modern-day Mexico, and he invited relatives to join him in New Spain. Though he was a devout Catholic, much of his family, including his nephew Luis, who worked as his main assistant, were crypto-Jews. Eventually the secret unraveled, and the family was arrested by the Inquisition in 1589. The younger Luis, his mother, and his sisters all asked for mercy and were placed in a monastery to serve out their penance. The uncle was stripped of his position and exiled; he died in prison.

A life story lost and found

Soon after the younger Carvajal was released from the monastery, he began to compose an electrifying spiritual autobiography. He was a trained calligrapher and he wrote his life story in tiny, lucid script in a small leather-bound book that he kept hidden on his person throughout his travels. In these writings, he charts the guiding hand of Providence in his spiritual adventures, and his last entry tells of his planned escape to Italy. Sadly, Carvajal and his family were arrested before they made it to safety, and the autobiography which was meant to declare God’s mercies was found and used by the Inquisitors as evidence against them.

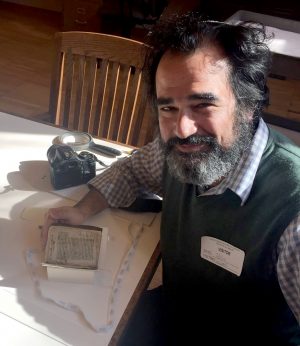

The author with the Luis de Carvajal manuscripts at the New York Historical Society (courtesy of author)

The autobiography, along with some of Carvajal’s other writings, were preserved with the extensive trial records and stored in the Mexican National Archives until they were mysteriously stolen in 1932. These documents were thought to have been lost for over eighty years, until they resurfaced and were identified as the long-lost texts by Leonard Milberg, a renowned collector. Milberg alerted the authorities and arranged for the return of these documents to Mexico.

Before their official return, however, the manuscripts were put on display at the New York Historical society, where I had a chance to look at them up close. I have been working on Carvajal’s life story for the past 15 years and I was overjoyed to finally see his handwriting and read the lines he penned with such passion. I—and all of the scholars who have investigated this sensational case of crypto-Jewish activity in the heart of colonial Mexico—had previously relied on a transcription of Carvajal’s autobiography made by Alfonso Toro a few years prior to the theft of the manuscripts. After many years living with this text, analyzing, contextualizing, and turning it around in my head, it was a real thrill to sit with the original, up close.

New discoveries, new questions

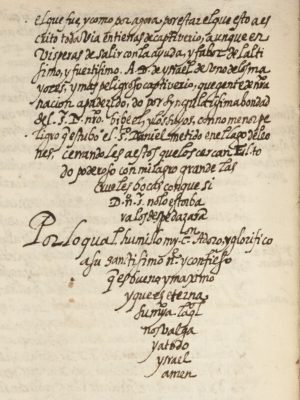

Final page of Luis de Carvajal’s spiritual autobiography, c. 1596 (Princeton University Digital Library)

The small bundle of manuscripts seemed to be inviting me in with their neat lines of tiny script. The first section was like meeting an old friend, or seeing the face of a longtime pen pal. I knew the lines of Carvajal’s autobiography inside and out, but I had never seen them in his own hand, nor did I know about the small side notes and elegant arrangement of the heading—the dedication to the Lord of Hosts that announces the beginning of his tale—nor the way he arranged the last lines in a final triangular flourish. Those details point to the fact that it was a text he went back to, added to, and revised. It also tells me that he really thought that he was about to escape the shadow of persecution and that his story of trials and tribulations was coming to a favorable end.

But then I encountered works I had never known about like El modo que es de Rezar, a guide to prayer for himself and for his fellow secret Jews in Mexico, and a list of the acts of mercy that the “most high God performed for Joseph”—a review of the major events of his short and tumultuous life.

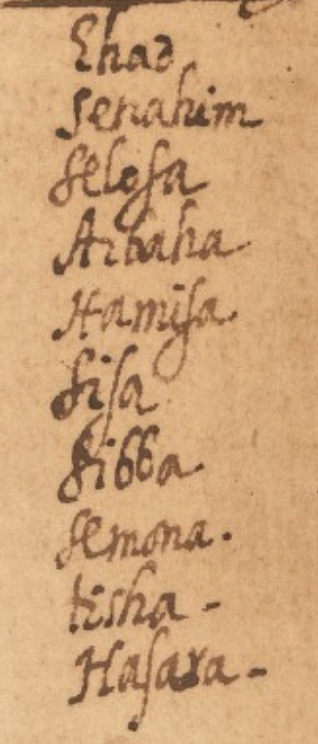

List of transliterated Hebrew numbers (detail), Luis de Carvajal manuscript, c. 1596 (Princeton University Digital Library)

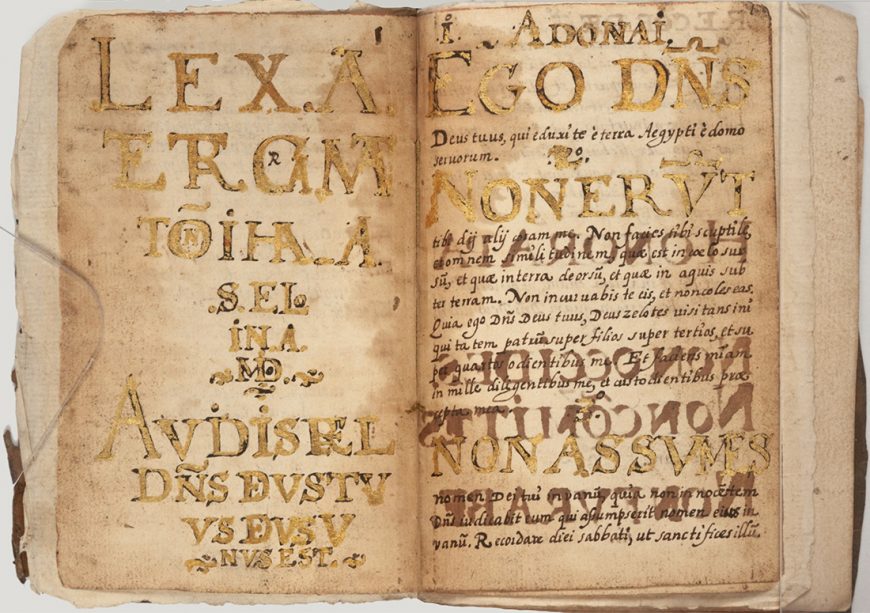

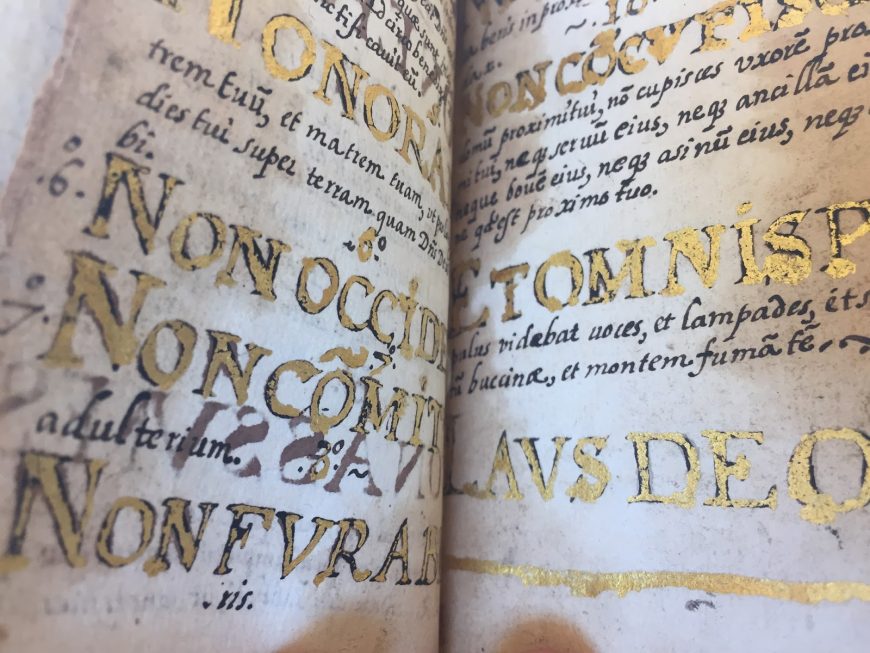

Right before this list, which takes up two pages, I found a section with the ten commandments in Latin, written out in beautiful large letters with gold leaf. New questions emerged: I knew Carvajal was an expert calligrapher, but where would he have had access to the materials and knowledge of the technique to apply the gold leaf?

There is another page towards the end with a list of Jewish holidays and their corresponding Christian dates, along with another column featuring the name of the Hebrew months and a list of transliterated Hebrew numbers from one to ten—a Hebrew primer for a fully Latinized Converso Jew? What follows is even harder to understand—some psalms in Latin and some prayers in Portuguese, along with some deeply cryptic lists that seem to be mystical codes waiting to be deciphered.

More to decipher

The story of the Carvajal family has intrigued historians of colonial Mexico and has caught the imagination of a wide range of Mexican intellectuals and artists. Their experience is often read as an exemplary tale of the abuses of religious authority and the struggle for freedom of belief. I believe that the story of the Carvajals also complicates and enriches our understanding of Latin American religious history and points to the diversity of colonial society and the dynamism of religious creativity and expression that can still speak to spiritual seekers today.

Now that these texts have been digitized and the originals are securely back in Mexico, scholars will be able to explore and ask more questions of these beguiling records of a vibrant and short-lived religious life.