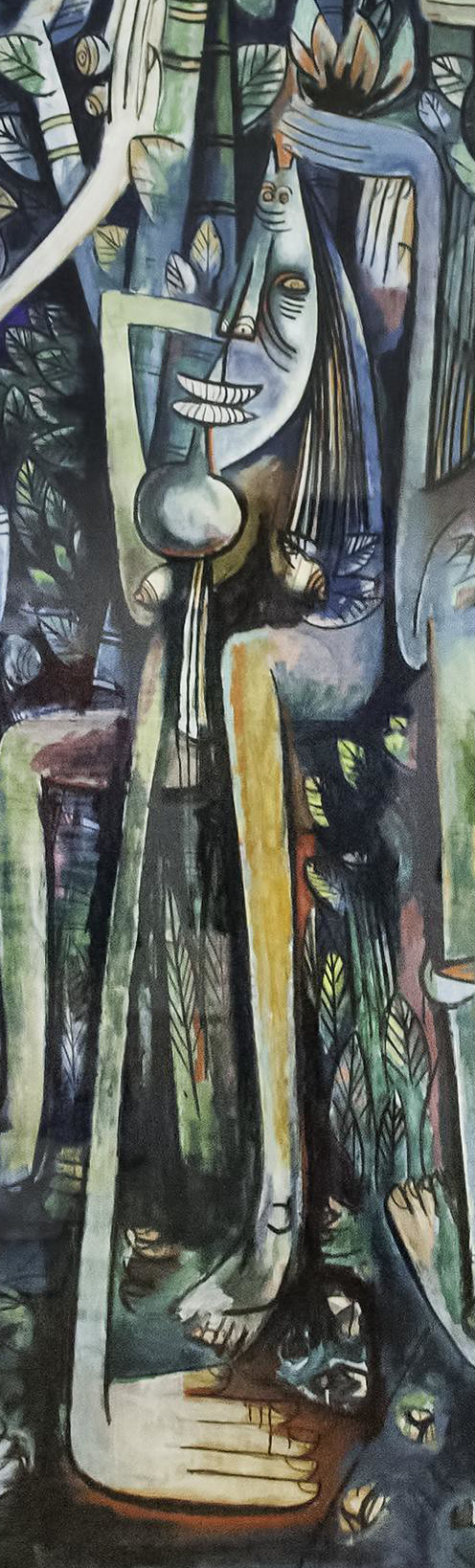

Wifredo Lam, The Jungle, 1942–43, gouache on paper mounted on canvas, 94–1/4 x 90–1/2″ / 239.4 x 229.9 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York, photo: Kent Baldner, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In The Godfather Part II Michael Corleone has the impeccable timing of visiting Cuba on the eve of the 1959 Revolution that would overthrow the corrupt government of Cuba’s leader at the time, Fulgencio Batista. Corleone’s stay in Havana—marked by business meetings with American corporations and trips to casino-resorts and cabaret shows—highlights the excesses that led to the dramatic fall of that regime during the film’s New Year’s Eve party. More than fifteen years earlier, when Wifredo Lam painted The Jungle (1943), Cuba had already spent over four decades at the mercy of United States-interests.

Wifredo Lam remains the most renowned painter from Cuba and The Jungle remains his best known work and an important painting in the history of Latin American art and the history twentieth-century modernism more broadly. In the 1920s and 30s, Lam was in Madrid and Paris, but in 1941 as Europe was engulfed by war, he returned to his native country. Though he would leave Cuba again for Europe after the war, key elements within his artistic practice intersected during this period: Lam’s consciousness of Cuba’s socio-economic realities; his artistic formation in Europe under the influence of Surrealism; and his re-acquaintance with Afro-Caribbean culture. This remarkable collision resulted in the artist’s most notable work, The Jungle.

A game of perception

Wifredo Lam, The Jungle (detail) (Museum of Modern Art, photo: Kent Baldner, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Jungle, currently on display at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, has an undeniable presence within the gallery: the cluster of enigmatic faces, limbs, and sugarcane crowd a canvas that is nearly an 8 foot square. Lam’s bold painting is a game of perception. The artist haphazardly constructs the figures from a collection of distinct forms—crescent-shaped faces; prominent, rounded backsides; willowy arms and legs; and flat, cloddish hands and feet. When assembled these figures resemble a funhouse mirror reflection. The disproportion among the shapes generates an uneasy balance between the composition’s denser top and more open bottom—there are not enough feet and legs to support the upper half of the painting, which seems on the verge of toppling over. Another significant element within Lam’s game of perception is how he places the figures within an unorthodox landscape. Lam’s panorama excludes the typical elements of a horizon line, sky or wide view; instead this is a tight, directionless snapshot, with only the faintest sense of the ground.

One part of the flora in this scene—sugarcane—is alien to the jungle setting suggested by the painting’s title. Sugarcane does not grow in jungles but rather is cultivated in fields. In 1940s Cuba, sugarcane was big business, requiring the toil of thousands of laborers similar to the cotton industry in the American South before the Civil War. The reality of laboring Cubans was in sharp contrast to how foreigners perceived the island nation, namely as a playground. Lam’s painting remains an unusual Cuban landscape compared to the tourism posters that depicted the country as a destination for Americans seeking beachside resorts. While northern visitors enjoyed a permissive resort experience, U.S. corporations ran their businesses, including sugar production. Though Cuba gained independence from Spain at the end of nineteenth century, the United States maintained the right to intervene in Cuba’s affairs, which destabilized politics on the island for decades.

European Modernism and Santería

During the interwar period in Paris, Lam befriended the Surrealists, whose influence is evident in The Jungle. Surrealists aimed to release the unconscious mind—suppressed, they believed, by the rational—in order to achieve another reality. In art, the juxtaposition of irrational images reveal a “super-reality,” or “sur-reality.” In Lam’s work, an other-worldly atmosphere emerges from the constant shifting taking place among the figures; they are at once human, animal, organic, and mystical.

This metamorphosis among the figures is also related to Lam’s interest in Afro-Caribbean culture. When the artist resettled in Cuba in 1941, he began to integrate symbols from Santería, an Afro-Cuban religion that mixes African beliefs and customs with Catholicism, into his art. During Santería ceremonies the supernatural merges with the natural world through masks, animals, or initiates who become possessed by a god. These ceremonies are moments of metamorphosis where a being is at once itself and otherworldly.

No cha-cha-cha

Lam created a new narrative within the Cuban imagination: rooted in the island’s complex history, his work was an antidote to the picturesque frivolity that mired the nation in stereotype,

[…]I refused to paint cha-cha-cha. I wanted with all my heart to paint the drama of my country, but by thoroughly expressing the negro [sic] spirit […] In this way I could act as a Trojan horse that would spew forth hallucinating figures with the power to surprise, to disturb the dreams of the exploiters. I knew I was running the risk of not being understood either by the man in the street or by the others. But a true picture has the power to set the imagination to work, even if it takes time. [1]

The Jungle is both enigmatic and enchanting, and has inspired generations of viewers to liberate their imaginations.

Notes

[1] Fouchet, Max-Pol. Wifredo Lam. New York: Rizzoli International Publications, 1976, 188–189. Republished in Richards, Paulette. “Wifredo Lam: A Sketch.” Callaloo 34 (Winter 1988): 91–92.