Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre)

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re standing in one of the largest galleries in the Louvre in Paris. It’s filled with enormous paintings. We’re looking at Jacques-Louis David’s “Oath of the Horatii.” This is a painting that was made in 1784 and exhibited in 1785, and this painting stole the show. It was absolutely new. Nobody had ever seen anything like it.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:25] The prevailing style in France was the Rococo. We could think about artists like Boucher or Fragonard, a style that appealed to the aristocracy.

Dr. Zucker: [0:35] Even in the kind of history painting that was made for the king, the style had become formulaic, it had become tired, but David’s “Oath of the Horatii” establishes a new style that we call Neoclassicism.

Dr. Harris: [0:47] Critics like Diderot are calling for an art that depicts virtuous behavior, very different from the prevailing Rococo style, and this painting answers that call.

Dr. Zucker: [0:59] This is the tail end of the period in France that we call the Enlightenment, with philosophers like Rousseau, Diderot, and Voltaire, who posit the idea that the rational should supersede tradition and the spiritual.

Dr. Harris: [1:09] The church was incredibly powerful, the monarchy in France was incredibly powerful, and the philosophers of the Enlightenment are asking questions about the validity of these very established institutions.

Dr. Zucker: [1:23] Remember, it will only be a few years before the French Revolution begins.

Dr. Harris: [1:27] Right, this is exhibited in 1785, the revolution is 1789.

Dr. Zucker: [1:31] The American Revolution has already taken place, based in large part on the ideas of French Enlightenment philosophers.

Dr. Harris: [1:37] We have a story from early ancient Roman history.

Dr. Zucker: [1:41] The early Roman state is at war with the neighboring city of Alba.

Dr. Harris: [1:45] But instead of the armies of each side going to war, they decide to send three brothers from each side to battle it out. Whoever survives is the side that’s victorious.

Dr. Zucker: [1:55] The Romans choose the Horatii, and the city of Alba chooses the Curatii.

Dr. Harris: [2:00] But things get very complicated because there are intermarriages between these two families. So no matter who wins…

Dr. Zucker: [2:09] Both sides will lose.

Dr. Harris: [2:10] Exactly.

Dr. Zucker: [2:11] What we see is the father of the Horatii holding swords aloft as the sons take an oath to battle to the death.

Dr. Harris: [2:18] For Rome.

Dr. Zucker: [2:19] On the right, we see three women and two children. There’s some disagreement as to who the woman in blue is in the back.

Dr. Harris: [2:26] We see two young women in the foreground. One of them is a Curatii sister, and she’s married to one of the Horatii brothers.

Dr. Zucker: [2:34] The other is a Horatii by birth, but will marry one of the Curatii.

Dr. Harris: [2:39] Families will be torn apart by this battle.

Dr. Zucker: [2:42] No matter what happens.

Dr. Harris: [2:43] By making the women appear so curvilinear, so passive, they don’t even have their eyes open, David is suggesting an idea that was very prevalent in the philosophy of Rousseau, for example, that women could not be true citizens of the state. They were unable to think about civic responsibility. Women could only think about the personal and the familial.

Dr. Zucker: [3:07] Look at how David has depicted that contrast. If the women are curvilinear, if their bodies are limp, the male figures are rigid. They are upright. They are tall. They are strong.

Dr. Harris: [3:19] They are angular in the forms of their bodies. They raise their arms together. There’s a sense of purpose that is completely absent from the women, who appear to be just victims of circumstance here.

Dr. Zucker: [3:33] The young men are working in unison. Their arms salute in unison. There is clearly a reverence for the idea of strength in a brotherhood, in a collective.

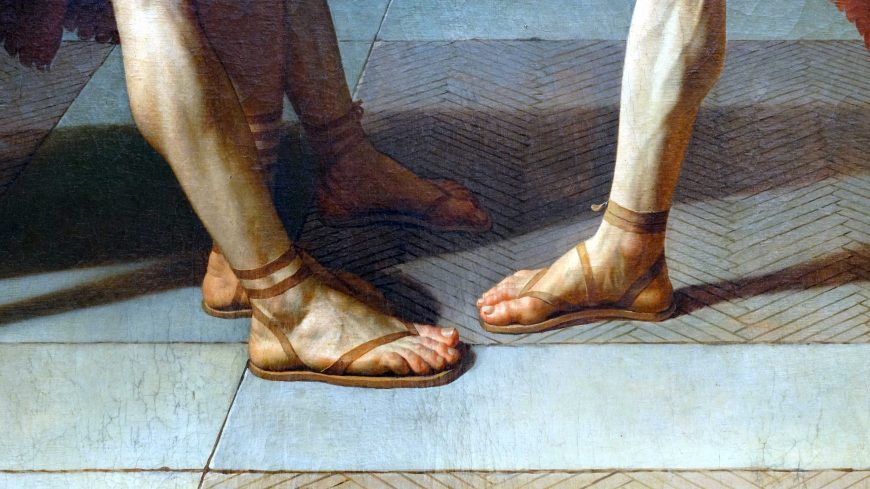

Dr. Harris: [3:43] David represents all of this in a classical, classicizing style, looking back to ancient Greece and Rome. There is an interest in the anatomy of the body, of carefully depicting the musculature, the movement of the body, that is directly from ancient Greek and Roman art.

Dr. Zucker: [4:03] In fact, the lighting, which rakes across the surface, reminds me of an ancient Greek or Roman relief carving. All of this is set within a simplified stone interior with rounded Roman arches, simplified Tuscan columns, and a pavement that creates a geometric stage for these figures.

Dr. Harris: [4:23] If we follow the orthogonal lines created by that pavement, we end at a vanishing point.

Dr. Zucker: [4:29] Right where the father’s hand clasps the swords.

Dr. Harris: [4:32] If we think about the lushness, the luxuriousness of Rococo painting, to me, this painting is the exact opposite. It’s one that speaks of the virtue of simplicity over the indulgence of the Rococo style, exactly what the Enlightenment philosophers were calling for artists to do.

Dr. Zucker: [4:52] Audiences recognized that stark contrast. In fact, the salon had to stay open longer than it had originally been scheduled just to accommodate the numbers of people that wanted to see it.

Dr. Harris: [5:02] One of the most fascinating things about this painting is that during the revolution, the brothers and their willingness to die for their country resonates with the revolutionaries, who must make sacrifices of themselves and their families for the ideals of the revolution.

Dr. Zucker: [5:20] David does become a revolutionary himself. It’s very tempting to read back into this painting, but we have to remember that the painting was completed several years before the revolution, although it was certainly informed by the same philosophical values that the revolution was founded on.

Dr. Harris: [5:36] David not only becomes a revolutionary, he votes for the beheading of the king. We’re talking about an artist who is very politically engaged.

Dr. Zucker: [5:46] This painting becomes an icon for the revolution.

Dr. Harris: [5:49] When I look at this painting, I sense that patriotic fervor that must have been so palpable in the early years of the revolution, when people were able to rise up against the abuses of a monarchy and to begin to imagine a republic for France.

[6:08] [music]

No one had seen a painting like it

In 1785 visitors to the Paris Salon (the official art exhibition organized by the Academy of Fine Arts) were transfixed by one painting, Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii. It depicts three men, brothers, saluting toward three swords held up by their father as the women behind him grieve—no one had ever seen a painting like it. Similar subjects had always been seen in the Salons before but the physicality and intense emotion of the painting was new and undeniable. The revolutionary painting changed French art but was David also calling for another kind of revolution—a real one?

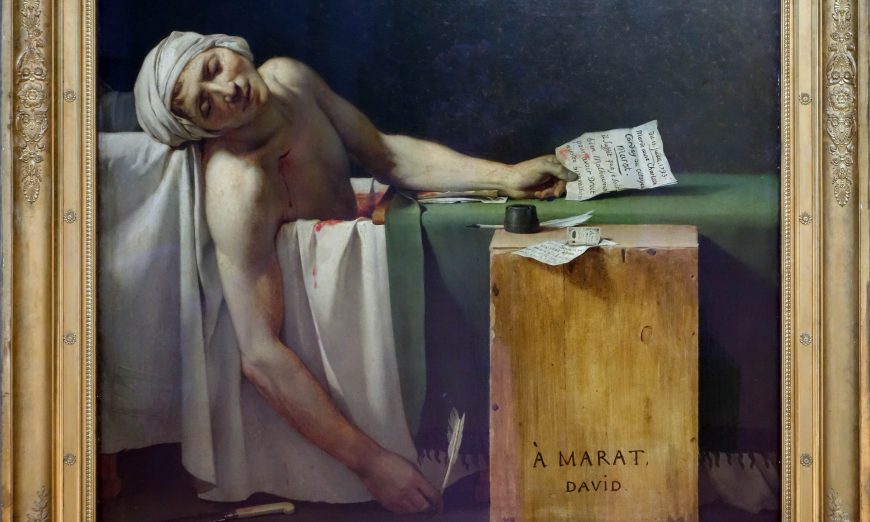

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Conquer or die

The story of Oath of the Horatii came from a Roman legend first recounted by the Roman historian Livy involving a conflict between the Romans and a rival group from nearby Alba. Rather than continue a full-scale war, they elect representative combatants to settle their dispute. The Romans select the Horatii and the Albans choose another trio of brothers, the Curatii. In the painting we witness the Horatii taking an oath to defend Rome.

Detail, Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The women know that they will also bear the consequence of the battle because the two families are united by marriage. One of the wives in the painting is a daughter of the Curatii and the other, Camilla, is engaged to one of the Curatii brothers. At the end of the legend the sole surviving Horatii brother kills Camilla, who condemned his murder of her beloved, accusing Camilla of putting her sentiment above her duty to Rome. The moment David chose to represent was, in his reported words, “the moment which must have preceded the battle, when the elder Horatius, gathering his sons in their family home, makes them swear to conquer or die.”

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A rigorously organized painting

To tell the story of the oath, David created a rigorously organized painting with a scene set in what might be a Roman atrium dominated by three arches at the back that keep our attention focused on the main action in the foreground. There we see a group of three young men framed by the first arch, the Horatii brothers, bound together with their muscled arms raised in a rigid salute toward their father framed by the central arch. He holds three swords aloft in his left hand and raises his right hand signifying a promise or sacrifice. The male figures create tense, geometric forms that contrast markedly with the softly curved, flowing poses of the women seated behind the father. David lit the figures with a stark, clinical light that contrasts sharply with the heightened drama of the scene as if he were requiring the viewer to respond to the scene with a mixture of passion and rationality.

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An example of Neoclassicism

In beginning art history courses, the painting is typically presented as a prime example of Neoclassical history painting. It tells a story derived from the Classical world that provides an example of virtuous behavior (exemplum vertutis). The dramatic, rhetorical gestures of the male figures easily convey the idea of oath-taking and the clear, even light makes every aspect of the story legible. Instead of creating an illusionistic extension of space into a deep background, David radically cuts off the space with the arches and pushes the action to the foreground in the manner of Roman relief sculpture.

Pierre Peyron, The Death of Alcestis, 1794, oil on canvas, 97.2 x 95.7 cm (North Carolina Museum of Art)

Before Oath of the Horatii, French history paintings in a more Rococo style such as Jean-François-Pierre Peyron’s Death of Alcestis (1785) involved the viewer by appealing to sentiment and presenting softly modeled graceful figures. David acknowledged that old approach in the figures of the women in Oath of the Horatii, but challenged it with the starkly athletic figures and resolute poses of the men.

Going back to Poussin

Before composing Oath of the Horatii, David went to see Poussin’s Rape of the Sabine Women and employed the lictor, the caped man, on the far left as the basis for the Horatii and he directly quoted other figures from Poussin as well. Even though Poussin was his model, David knew that he was creating a new type of painting and wrote, “I do not know whether I shall ever paint another like it,” as he developed the austere composition and powerful physiques.

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Personal sacrifice for an ideal

Today the painting is typically interpreted in the context of the French Revolution and David’s own direct involvement as a revolutionary. The exact source of the scene that inspired David is in doubt but it is important to art historians because it can offer clues as to David’s intentions for the picture.

In the nineteenth century a former student of David identified the source as the 1640 play Les Horaces by Corneille that David had seen in Paris in 1782. The difficulty is that no scene of an oath occurs in Corneille’s script. However, toward the end of the play, a minor character comes on stage bearing the three swords of the defeated Curatii. This stage direction as well as other contemporary productions and images related to the story of Horatii in particular—and oath-taking in general—may provide the background for David’s decision to paint the moment when the brothers take their oath to defend Rome—an act of personal sacrifice for a political ideal.

Jacques-Louis David, Oath of the Horatii, 1784, oil on canvas, 3.3 x 4.25 m, painted in Rome, exhibited at the salon of 1785 (Musée du Louvre, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Revolutionary or not?

With this in mind, we can understand how one might read Oath of the Horatii as a painting designed to rally republicans (those who believed in the ideals of a republic, and not a monarchy, for France) by telling them that their cause will require the dedication and sacrifice of the Horatii. Those who support this view cite some of the rousing lines from Corneille’s tragedy such as, “Before I am yours, I belong to my country,” as well as the response of contemporary left-wing writers who praised David’s republican sentiments. Those who disagree with this interpretation argue that David was enmeshed in the system of royal patronage, that the painting was accepted into the Salon with no negative response from official quarters and later royal commissions followed.

In the succeeding decades French painters responded again and again to David’s transformative painting. Paintings such as Gros’ Napoleon Bonaparte Visiting the Plague-Stricken (1804), Gericault’s Raft of the Medusa (1819), Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830), and even Courbet’s Burial at Ornans (1849) confront the Oath of Horatii as they embrace or reject David’s aesthetic and, perhaps, political revolution.