Jean-Baptiste Martin, A Meeting of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture at the Louvre, c. 1712–21, oil on canvas, 30 x 43 cm (Louvre)

In a room filled to the brim with painting and sculpture, well-dressed men in powdered wigs assemble around a desk while stragglers chat with their neighbors. Jean-Baptiste Martin’s small painting depicts a meeting of the distinguished French art academy without an artist’s tool in sight—only the ornate room situates the scene in the Louvre palace. The choice to not show the artists at work, but rather as fashionable gentlemen engaged in sociable intellectual exchange speaks directly to the early history of the French Royal Academy.

The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) was established in 1648. It oversaw—and held a monopoly over—the arts in France until 1793. The institution provided indispensable training for artists through both hands-on instruction and lectures, access to prestigious commissions, and the opportunity to exhibit their work. Significantly, it also controlled the arts by privileging certain subjects and by establishing a hierarchy among its members. This hierarchical structure ultimately led to the Académie’s dissolution during the French Revolution. However, the Académie in Paris became the model for many art academies across Europe and in the colonial Americas.

Foundation

This preeminent training organization for painters and sculptors was founded in response to two related concerns: a nationalistic desire to establish a decidedly French artistic tradition, and the need for a large number of well-trained artists to fulfill important commissions for the royal circle. Previous monarchs had imported artists (primarily from Flanders and Italy), to execute major projects. In contrast, King Louis XIV sought to cultivate and support French artists as part of his grander project of self-fashioning, with art playing a vital role in the construction of the royal image.

The Académie quickly rose to prominence, in conjunction with the Ministry of Arts (responsible for construction, decoration, and upkeep of the king’s buildings) and the First Painter to the King—the most prestigious title an artist could achieve. Two men were integral to the institution’s early history: Jean-Baptiste Colbert, an increasingly influential statesman who acted as the institution’s protector, and the artist Charles Le Brun, who would go on to be both First Painter and the Académie’s Director. Both men sought to elevate the status of artists by emphasizing their intellectual and creative capacities, and both sought to differentiate members of the Académie—academicians— from guild members (guilds were a medieval system that strictly regulated artisans). The Académie, whose members were financially supported by the King, moved into its permanent location at the Louvre Palace in 1692, further reinforcing the institution’s status. Given such institutional preoccupations, Martin’s decision to show artists as gentlemen socializing rather than as artisans laboring takes on new significance.

Hierarchies

From its inception, the Académie was structured around hierarchy. There were distinct levels of membership that an artist could advance through over time. In art, too, there was a hierarchy: painting was prioritized over sculpture, and certain subjects were considered more noble than others. To become a member, artists submitted work for evaluation by academicians, who accepted them at a certain level, based on the kind of subjects they aspired to paint. If they passed this first phase, applicants would execute a “reception piece” depicting a subject chosen by the academicians.

The Académie divided paintings into five categories, or genres, ranked in terms of difficulty and prestige:

- History Painting—encompassing highbrow subjects taken from the classical tradition, the bible, or allegories, this type of painting was considered the highest genre because it required proficiency in depicting the human body, as well as imagination and intellect to depict what could not be seen. These were often large-scale multi-figure paintings.

- Portraiture—focusing on capturing likeness, this genre was prestigious, and certainly lucrative, but less so than history painting. Portraitists were derided for “merely” copying nature rather than inventing (an oversimplification as few portraits were executed entirely from life).

- Genre Painting—depicting scenes of everyday life, this genre included the human figure but ostensibly did not represent grand ideas, although many genre paintings had moralizing undertones. Genre paintings were smaller in size than history paintings, further detracting from their prestige.

- Landscapes—consisting of all representations of rural or urban topography, real or imagined, this genre became especially popular during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

- Still Life Painting—often indulging in the juxtaposition of colors and textures, these paintings represented inanimate (often luxury) objects and drew heavily on the seventeenth-century Dutch tradition of such subjects. While at times other moralizing symbols such as memento mori (reminders of human mortality) were included, these were not an intrinsic part of the genre, which was considered to require no invention on the part of the artist (since, they were painting what they could see).

Training

Benoît-Louis Prévost, after Charles-Nicolas Cochin, “The School of Art” (“Ecole de dessein”), planche I. Recueil de planches sur les sciences, les arts libéraux, et les arts mécaniques, avec leur explications, volume 3 (Paris, 1763)

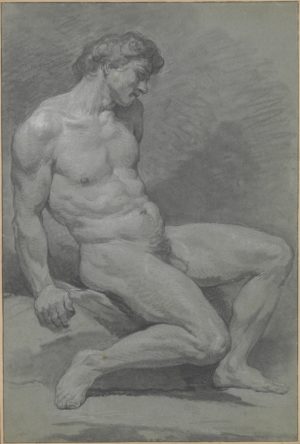

Nicolas Bernard Lépicié, Seated Male Nude Facing Right, mid-18th century, charcoal, stumped, black chalk heightened with white on gray-green paper, 50.7 x 34 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

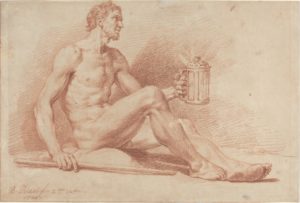

Academic instruction was centered on drawing (following the precedent of Italian drawing schools established in the sixteenth century). The Académie maintained a rigid curriculum to instruct artists, as recorded in contemporary accounts and depictions. An etching illustrating a 1763 description of the “school of art” shows how students first learned to draw by copying drawings and engravings (seen on the left) before moving on to drawing plaster casts to learn how to translate the three-dimensional form into two dimensions (seen at center). Students would then copy large-scale sculpture (as seen at the right-most edge) before being allowed to draw the live nude model (as seen in the middle-right portion, slightly set back from the foreground). Drawing the male nude form was the bedrock of the Académie’s curriculum, an essential building block for painters, particularly those destined to produce history paintings. Students produced many single-figure nude studies, known as académies, such as this example from Nicolas Bernard Lépicié. Props could be added subsequently to transform the posed bodies into identifiable figures, as Bernard Picart has done with the drawing Male Nude with a Lamp, where the figure, with the addition of a lamp, becomes the philosopher Diogenes.

Bernard Picart, Male Nude with a Lamp (Diogenes), 1724, red chalk on laid paper,30.9 x 45.7 cm (National Gallery of Art)

In a lively drawing, Charles Natoire depicts himself in a red cape in the left foreground, providing feedback on students’ drawings. The majority of students work independently, focused on the two nude models in an intertwined pose selected by the supervising professor. The opportunity to study two interacting male bodies was a rarer and more challenging exercise.

Charles Joseph Natoire, Life Class at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, 1746, pen, black & brown ink, grey wash & watercolour & traces of pencil over black chalk on laid paper, 45.3 x 32.2 cm (The Courtauld Gallery)

Outside of the Académie’s official spaces, academicians would provide advanced students opportunities to draw nude female models. In addition to supervising drawing education, each professor selected students to be part of his studio. This is where artists actually learned to paint or sculpt by emulating their teacher, often contributing to his large-scale commissions. Studio practices varied, and not all studio members were necessarily enrolled Académie students.

Both academicians and students attended lectures addressing theoretical and practical aspects of artistic practice, such as the importance of expressions or how to apply paint to ensure longevity. These were offered by professors and so-called amateurs. These honorary Académie members were not professional artists but art lovers and “friends of artists”—often from the nobility—who advised artists on questions of composition, aesthetics, and iconography and often championed certain artists, sometimes as patrons or collectors.

The draw of Rome

The classical tradition was central to the Académie’s curriculum. In 1666, the Académie opened a satellite in Rome to facilitate students’ study of antiquity. In 1674, the Académie established the Prix de Rome (Rome Prize), a prestigious award that allowed its most promising artists to study in Rome for three to five years. While the focus of the French Academy in Rome was facilitating the study of classical antiquity, students also drew after important Renaissance and Baroque artworks, as seen in Hubert Robert’s red chalk drawing depicting an artist copying Domenichino’s fresco in a Roman church.

Hubert Robert, Draftsman in the Oratory of S. Andrea, S. Gregorio al Celio, 1763, red chalk, 32.9 x 44.8 cm (Morgan Library & Museum)

While in Rome, these Académie students—called pensionnaires—studied canonical artworks and regularly sent their drawings and copies after important works back to Paris to demonstrate their progress. Although not part of the formal curriculum, most artists explored the Roman environs, taking inspiration from the rich landscape, diverse topography, and colorful scenes of peasant life. Important connections were forged in Rome with other artists, patrons, and supporters.

Salons and the rise of public opinion

Beginning in 1667, the Académie established exhibitions to provide members with the crucial opportunity to display their work to a wider audience, thereby cultivating potential patrons and critical attention. Held annually and, later, biannually, these exhibitions came to be known as Salons, after the Louvre’s salon carré where they took place after 1725. The Salon became a significant space of artistic exchange and an important opportunity to view art prior to the formation of the public art museum.

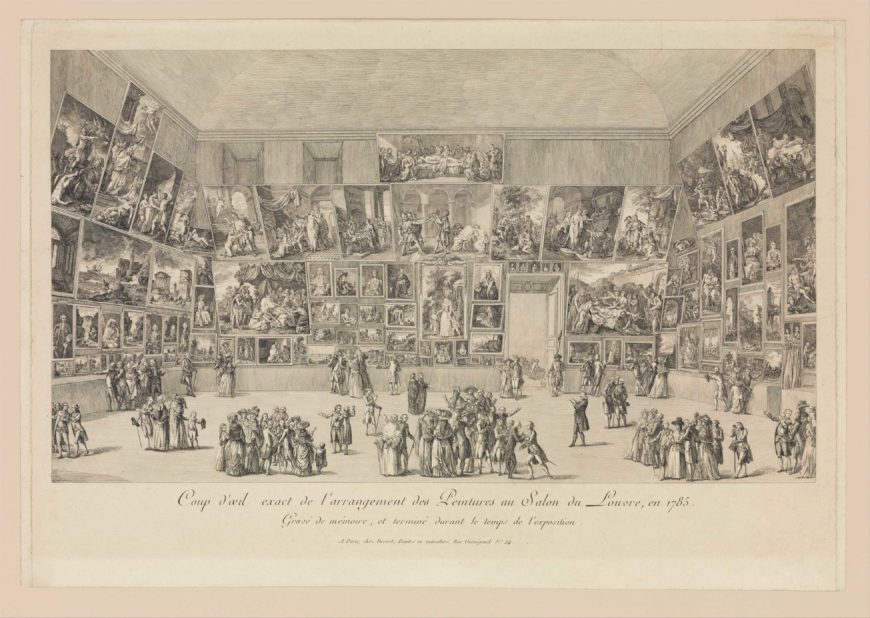

Pietro Antonio Martini, View of the Salon of 1785, 1785, etching, 27.6 x 48.6 cm (image), 36.2 x 52.7 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Artworks in the Salon were selected by a jury of academicians. Paintings were displayed according to size and genre, with larger works (history painting and portraiture) occupying the more prestigious higher levels, as can be seen in an engraving of the Salon of 1785 where Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii features prominently in the center. With the 1737 introduction of a broader public to the Salon came the advent of public opinion and the emergence of art criticism. The Académie published a booklet that listed the displayed works, organized by the artist’s rank, called the livret. Art collectors and learned Salon-goers penned opinions analyzing the artistic and intellectual merit of the exhibited artworks; some of these, like those written by philosopher Denis Diderot, were meant for a small community of like-minded individuals both in France and beyond, but increasingly art criticism was printed in newspapers for access by a broader public.

Genders and genres

The Académie was a male space, for the most part; some painters accepted female students in their studios, particularly in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Women artists were barred by propriety from studying the male nude figure, a core aspect of Academic training. This rendered them unable to become officially recognized history painters, and they were therefore restricted to genres considered to be less intellectually rigorous. During its 150-year long history, the Académie only welcomed four women as full members: Marie-Thérèse Reboul was admitted in 1757; Anne Vallayer-Coster was admitted in 1770; Adélaïde Labille-Guiard and Elisabeth Vigée-LeBrun were both admitted in 1783.

This was the artist’s reception piece for the Académie. Elisabeth Louise Vigée Le-Brun, Peace Bringing Back Abundance, 1780, oil on canvas, 103 x 133 cm (Louvre)

Despite their acceptance to the Académie, these women had limited options. Painting primarily still-lifes (like Reboul), Vallayer-Coster elevated that genre with large-scale ornate compositions. Labille-Guiard led a large studio of female students and was well-known as a prominent portraitist. So too did Vigée-LeBrun, who pushed the boundaries of genre and her gender by occasionally painting allegories, including her reception piece for the Académie. Familial connections (in the case of Reboul, Labille-Guiard, and Vigée-LeBrun) or royal protectors (in the case of Vallayer-Coster, Labille-Guiard, and Vigée-LeBrun) played vital roles in their success. Without such champions, female artists were unable to penetrate the patriarchal institution of the Académie. Still, their work and personal lives were subjected to undue public scrutiny and their achievements were often maligned.

Abolition and afterlives

In the 1780s, the Académie came under attack by members and outsiders for politicizing the distribution of prizes and honors. Its rigid hierarchies, inequitable structures, and rampant nepotism were incompatible with the Revolution’s core values of Liberty and Equality. Major artists who had benefited from the institution lobbied for its dissolution. With the overthrow of the monarchy and Louis XVI’s execution, institutions with indelible royal connections were scrutinized and deemed irrelevant. The Académie was abolished on August 8, 1793 by order of the National Convention.

After several years of hardship for artists brought about by the erosion of royal, noble, and ecclesiastical patronage during the Revolution, the Directory government revived many of the structures of the Académie in establishing a National Institute of Sciences and Arts (Institut nationale des sciences et des arts, subsequently Institut de France) in 1795. The new organization’s membership included many former academicians, who reinstated certain aspects of the now-defunct Académie, such as the Rome Prize in 1797. The hierarchy of genres, inculcated in the Académie’s members and audiences, remained central to understanding the arts throughout the nineteenth century.

Additional resources

Institut de France

Denis Diderot, Salons (tome I – III), Paris: J.L.J Briere Libraire, 1821

The Salon and the Royal Academy in the Nineteenth Century

Laura Auricchio, Melissa Lee Hyde, Mary Sheriff, and Jordana Pomeroy, Royalists to Romantics: Women Artists from the Louvre, Versailles, and Other French National Collections (Scala Arts Publishers, Inc., 2012).

Colin B Bailey, “‘Artists Drawing Everywhere’: The Rococo and Enlightenment in France,” in Jennifer Tonkovich et al., Drawn to Greatness: Master Drawings from the Thaw Collection (New York: Morgan Library & Museum, 2017).

Albert Boime, “Cultural Politics of the Art Academy,” The Eighteenth Century vol. 35, no 3 (1994), pp. 203–22.

Thomas E. Crow, Painters and Public Life in Eighteenth Century Paris (Yale University Press, 1985).

Christian Michel, The Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture: The Birth of the French School, 1648–1793, translation by Chris Miller (The Getty Research Institute, 2018).

Richard Wrigley, The Origins of French Art Criticism: from the Ancien Régime to the Restoration (Oxford University Press, 1993).