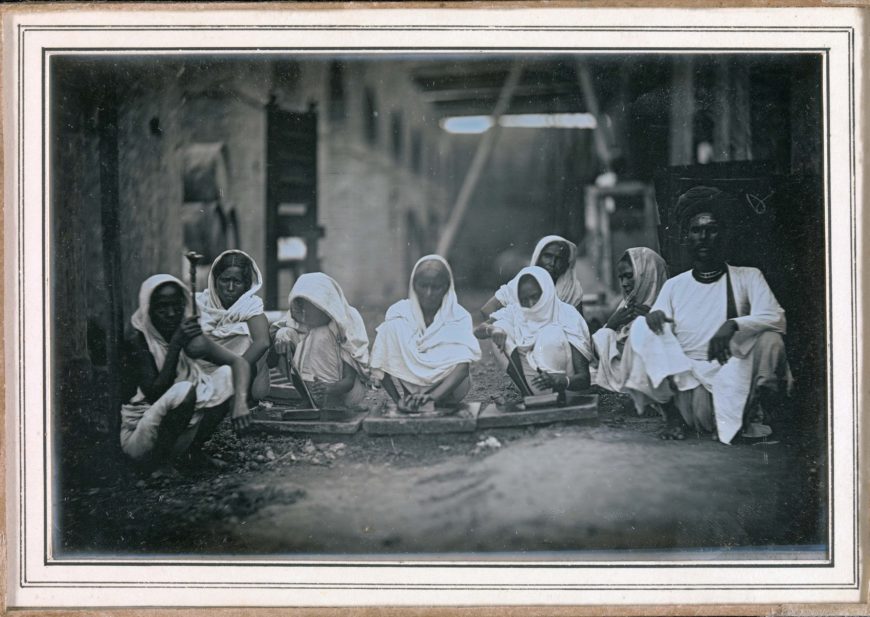

Photograph inscribed “Women Grinding Paint,” Calcutta, India, c. 1845, daguerreotype, 9.4 x 14.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Photography’s early history in India

On August 19, 1839, the invention of a new photographic method, the Daguerreotype process, was announced to the public at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in Paris. In December of the very same year, the Bombay Times in India published three articles on the arrival of the new Daguerreotype camera. As early as 1840, hardly a year after photography had first developed in Europe, the Calcutta firm of Thacker & Company were importing and advertising the sale of the Daguerreotype camera in the daily paper Friend of India. Far from a belated version of European photography, photography in India developed rapidly and in parallel with European photographic practices. In fact, the new technology of photography was very well received in nineteenth-century India and would be taken up by aspiring amateur photographers, commercial photographers, photojournalists, and colonial state officials with much enthusiasm. Coinciding with the expansion of British imperial rule, photography lent itself to the geographical and cultural exploration of the British Empire’s colonies. Nineteenth-century photographs thus elucidate the instrumental role of the camera in the study, documentation, and representation of India’s cultures, people, and landscapes during a period of colonial governance.

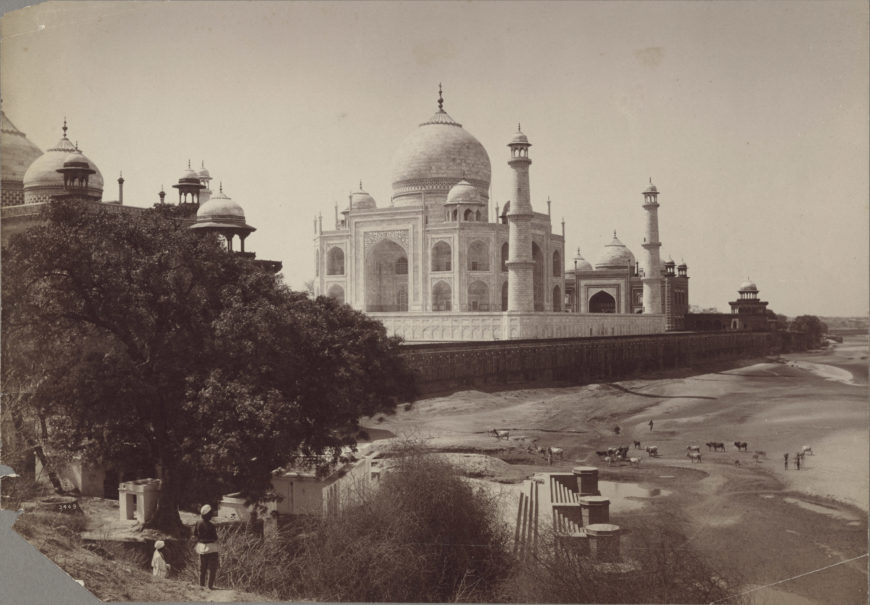

![John Murray, Distant view of the Taj from the East, [Agra], 1855, photographic print (The British Library)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/019PHO000000101U00009000SVC2-1.jpg)

John Murray, Distant view of the Taj from the East, [Agra], 1855, photographic print (The British Library)

European photographers in India

At first, photography served as the leisurely pursuit of wealthy Indians, European officers and travelers, and other aspiring amateur photographers. Dr. John Murray of the Bengal Medical Service was one such amateur photographer. Murray began his experimentations with photography when he moved to the city of Agra (located today in the northern Indian state of Uttar Pradesh) in 1848. During his stay, he produced a series of views of the Mughal monuments of Agra (such as the Taj Mahal), Delhi, Fatehpur Sikri, and other nearby sites, which not only satisfied his own fascination with the technology but contributed to an emergent visual archive of the landscapes and landmarks of India.

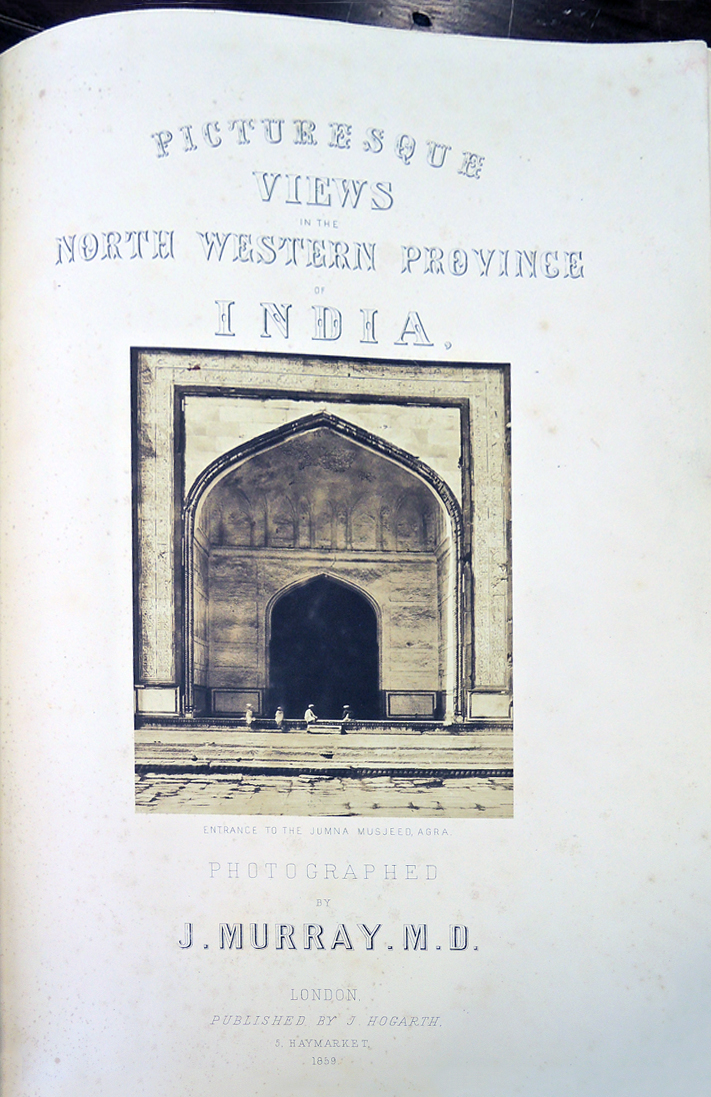

Murray achieved recognition for his work when his photographs were published under the titles Photographic Views of Agra and Its Vicinity and Picturesque Views of the North Western Province of India in 1857 and 1859 respectively. These early photographs of India allowed those who had not traveled to the subcontinent to see and know India from the comfort of their own home.

India and the picturesque

The 1860s saw the growing dominance of commercial photography in India, as European photographers, following in the footsteps of earlier traveling artists, increasingly visited India to produce photographs for sale and publications. European artists first began to travel to India after the 1750s and disseminate visual information about the country’s landscapes, architecture, and peoples—alongside the expansion of European colonial powers in India. During the nineteenth century, European artists, both professional and amateur, journeyed to India in even greater numbers in search of picturesque scenery to be captured by the painter’s brush and, thereafter, the photographer’s camera.

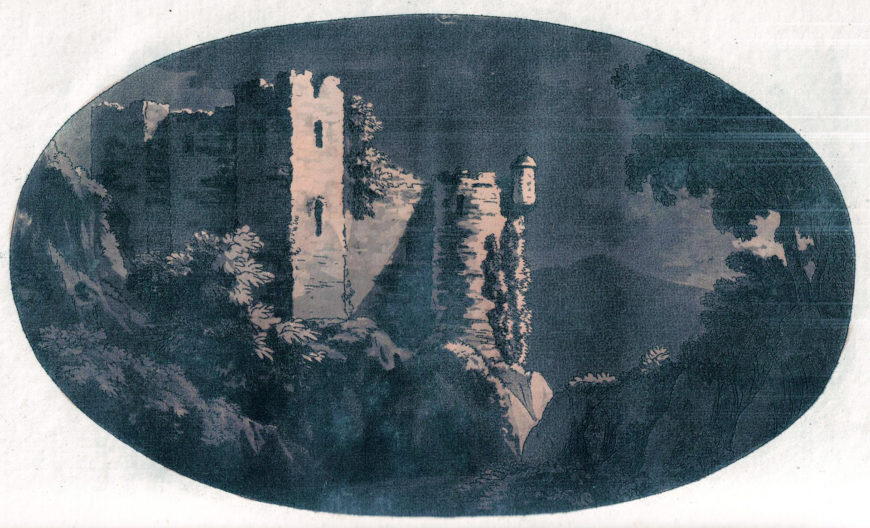

“Penrith Castle, Cumbria, England,” in William Gilpin, Observations…. (Cumberland & Westmoreland, 1786)

Like earlier landscape painters, travel photographers from Britain held certain expectations of what they hoped to find in the regions to which they traveled and framed their views of the country through specific aesthetic principles known as the picturesque. Components of picturesque landscapes included a body of water, strategically placed foliage, a rustic bridge, evidence of human presence, and more broadly, a sense of sublime, awe-inspiring beauty. The picturesque was devised in the eighteenth century by English critics such as William Gilpin, whose guidebooks defined the manner in which nature should be visually represented.

Attributed to Samuel Bourne, Gangootri, Uttarakhand, India, October 21, 1865, albumen silver print, 23.6 x 29.5 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

These key features are present in the work of Samuel Bourne—one of the most important British commercial photographers working in nineteenth-century India who created hugely successful photographic studios in Shimla (1863), Calcutta (1867), and Bombay (1870) with his partner Charles Shepherd. An 1865 photograph showing Gangootri from one of Bourne’s three arduous treks to the Himalayas, for example, depicts a gently flowing river, a makeshift wooden bridge, and a stone temple or dwelling set against the backdrop of imposing mountainous terrain, underlying the photographer’s reliance on the aesthetic parameters of the picturesque.

Bourne’s widely disseminated picturesque photographs of India’s temples, mountain ranges, cityscapes, and landscapes played a vital role in shaping foreign perceptions of the subcontinent. Picturesque landscape views produced a simplified vision of India, seemingly untouched and in want of modern civilization. Within this aesthetic framework, Indians were reduced to mere aesthetic elements, devoid of agency and individuality. In the context of European colonialism, the picturesque aesthetic can, in this way, be read as an ideological tool mobilized to support colonial intervention.

Lala Deen Dayal, Faluknuma Palace, Hyderabad, India, 1888, albumen silver print; 19 x 26.7 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

An Indian photographer

European photographers or studios were not the only successful photographic enterprises in India; Indian photographers and local studios achieved considerable success as well, producing views of India that both intersected with and deviated from the aesthetic norms of European photography.

Lala Deen Dayal, General View of Sanchi Tope, Bhopal District, 1885–87, albumen silver print, Sanchi, India, 18.1 × 26.2 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

Of all Indian photographers, Lala Deen Dayal distinguished himself with an impressive photographic oeuvre, even more diverse than any European photographer or firm. Deen Dayal began his career in the mid 1870s, and, by 1884, had been appointed as the court photographer for the royal house of Hyderabad. By the end of the century, Deen Dayal had opened his own studios in cities such as Indore (mid 1870s), Secunderbad (1886), and Bombay (1896), and even a zenana (or women’s only) studio in Hyderabad, for women who observed purdah (the cultural practice of veiling and secluding women (1892). Over the course of his career, Deen Dayal moved freely between Anglo-Indian and princely Indian worlds, working for diverse patrons that ranged from colonial and state officials to royal houses and elite Indian families. For his royal patrons, Deen Dayal produced views that emphasized the regal splendor of princely India—such as his photo of Faluknuma Palace.

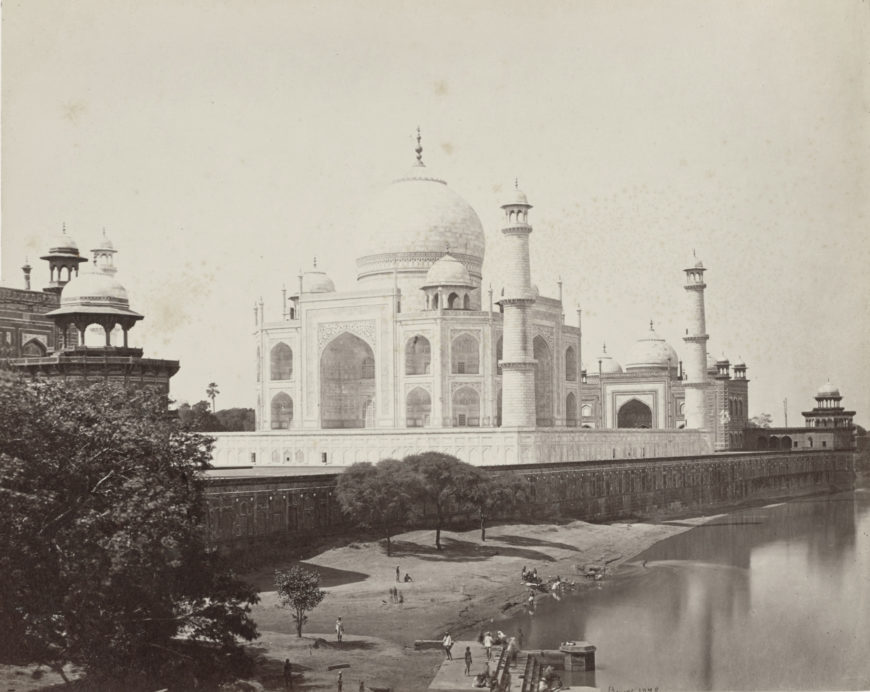

Lala Deen Dayal, The Taj (Rear View), Agra, India, 1885–87, albumen silver print, 18.5 × 26.5 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

At the same time, to compete with European photographers and appeal to the tastes of Western audiences, Deen Dayal produced architectural and landscape views that conformed to the aesthetic standards of photography set by European photographers, as seen in Deen Dayal’s and Bourne’s photographs of the Taj Mahal.

Samuel Bourne, Agra; The Taj, from the River, 1865–1866, albumen silver print; 23 × 28.7 cm (The J. Paul Getty Museum)

Local photographic studios

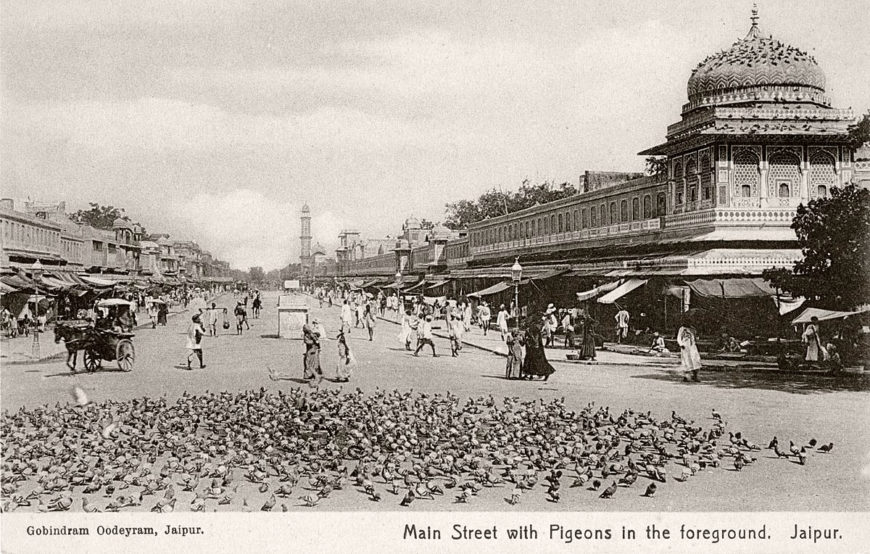

By the turn of the twentieth century, professional, Indian-run local photography studios had been established in virtually every moderately-sized town in India. Gobindram & Oodeyram, a studio established in the late 1880s in the city of Jaipur, the former royal capital of the Kacchwaha kingdom (now the capital of the western Indian state of Rajasthan) is one such example. Given its location in Jaipur, the studio specialized in photographs of the city and its environs.

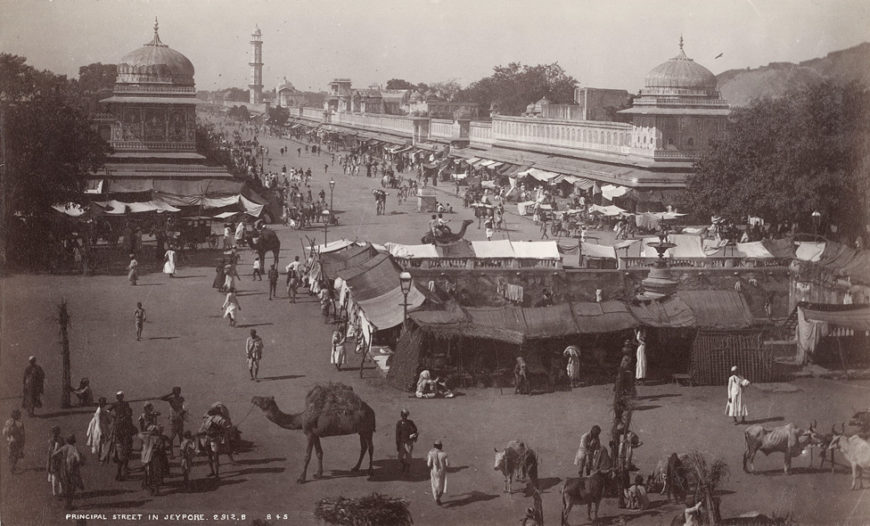

Bourne and Shepherd, Principal street in Jeypore, 1885, photograph, 28 x 17 cm (The British Library)

Several of these views and landmarks had already been captured by Bourne & Shepherd and Deen Dayal. For instance, the principal street of Jaipur (spelled Jeypore earlier) was photographed by Bourne & Shepherd in 1885, Deen Dayal in 1895, and Gobindram & Oodeyram in 1905, suggesting that a shared visual language had developed between British and Indian, local and pan-Indian photographers in nineteenth-century India.

Deen Dayal and Lala, Street view, Jeypur, 1895, photograph, 28 x 19.2 cm (The British Library)

![Gobindram and Oodeyram, [Street scene in] Jaipur City, 1905, 19.6 x 25.9 cm (The British Library)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/019PHO0000017S4U00057000SVC2-870x663.jpg)

Gobindram and Oodeyram, [Street scene in] Jaipur City, 1905, 19.6 x 25.9 cm (The British Library)