Seated Buddha: The earliest image of the Buddha in China that we know of.

Read Now >Chapter

The Silk Roads

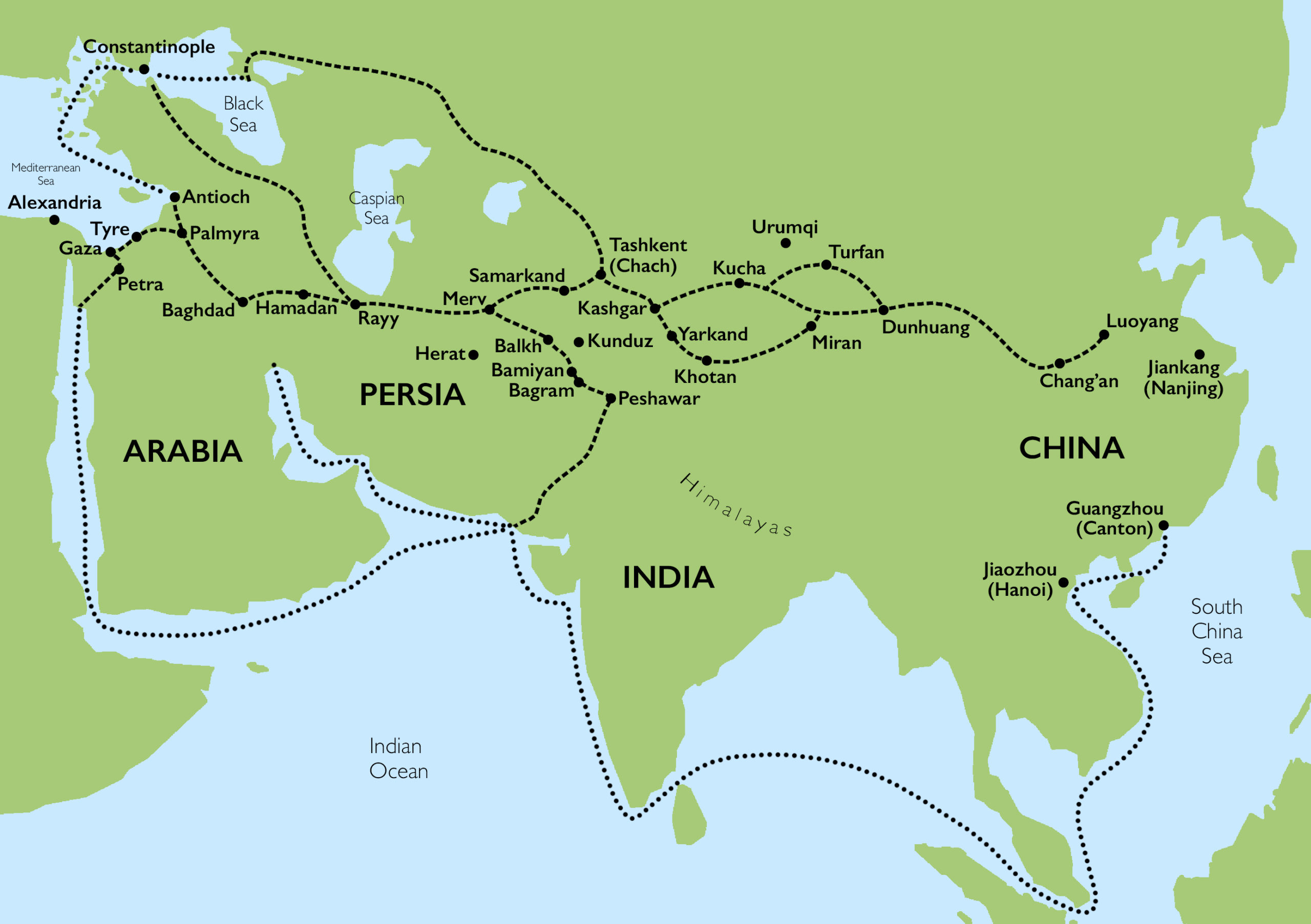

Map showing the trade routes that made up the Silk Roads (map by Evan Freeman, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, adapted from Françoise Demange, Glass, Gilding, and Grand Design: Art of Sasanian Iran (224–642) (New York: Asia Society, 2007)

The name “Silk Road” is familiar to many, conjuring up caravan trains of camels crossing deserts weighed down by exotic goods such as tea, spices, medicines, and crucially, silk, but the reality of the Silk Roads was both more complex and more ordinary. The Silk Roads were a network of trade routes that connected towns and peoples across Asia that flourished from about 200–900 C.E. but existed from about 100 B.C.E. through the mid-1400s C.E. The foundation of the “Silk Roads” is attributed to Han dynasty envoy, Zhang Qian, whose mission to Central Asia in 114 B.C.E. brought the Chinese court into direct contact with kingdoms in Central Asia.

Roman glassware and other objects have been found in China, Korea, and Japan. Pitcher, Roman (made in Syria), late 4th century, glass, 25 cm high, excavated from the 5th-century (Silla) south mound of Hwangnamdaechong Tomb in Gyeongju, South Korea (Gyeongju National Museum, Korea, National Treasure 193)

The phrase “Silk Road,” invokes a pre-modern cross-continental highway, but the idea of a road meandering across Asia is relatively recent. The name “Silk Road” was given to the network of ancient trade routes crossing Asia by the German traveler and geographer Baron Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877. Goods (including art objects, textiles, medicine, and foods) and ideas (including religious thought and philosophical concepts) certainly traveled very impressive distances along these trade routes, but most of the travel was relatively local in scope.

Many of the same routes continued to be used by later traders and travelers, but the combination of short and long-distance trade that characterized these overland routes shifted beginning in the 10th century. This occurred for several reasons, including the fall of the Tang dynasty in China; the rise of maritime trade routes through Southeast Asia that allowed for goods and people to travel long distances much more quickly; and the absorption of communities of Sogdians, merchants who were responsible for much of the long-distance Silk Road trade, by Islamic empires. Pan-Asian exchange flourished again in the Mongol period in the 13th and 14th centuries which saw Mongol rule over most of Asia, sometimes following the old Silk Roads overland, sometimes following the maritime trade routes that had been established between the decline of the overland Silk Roads and rise of the Mongols.

Detail of the wall mosaic depicting the attendants of empress Theodora’s wearing luxury silk garments of diverse designs, 540s, San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Asia is the primary focus of Silk Road trade, but it can be argued that the Silk Roads extended as far west as Rome, as attested by the presence of Roman glass bowls and other objects found in tombs in China and the Korean peninsula. Chinese silk was also highly sought after by Roman elites beginning as early as the second century B.C.E. Beginning in the fourth century C.E., the interconnectivity between Central Asia and the Eastern Roman Empire, which brought Asian goods into the Mediterranean, can also be understood as part of the Silk Roads.

This chapter will focus on the core of the Silk Roads, between Central and East Asia, but it is important to keep in mind that the “Silk Roads” extended further west and south than we have the space to cover here.

Ideas and Religion along the Silk Roads

This is the earliest known dated Buddha sculpture produced in China. Buddha (detail), 338, Later Zhao Kingdom, bronze with gilding, China, Hebei province, 16 inches tall (Asian Art Museum)

Many ideas and philosophical concepts were carried along the Silk Roads. Buddhism was arguably the most far-reaching of these. Buddhism originated in India in the 5th or 4th century B.C.E., and soon spread out of India to the east and west via the Silk Roads, arriving in China sometime in the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E.– 220 C.E.). Some of the earliest Buddhist art objects to arrive in China were portable Buddhas brought from Central Asia to China by Buddhist monks, which may have served as objects of personal devotion.

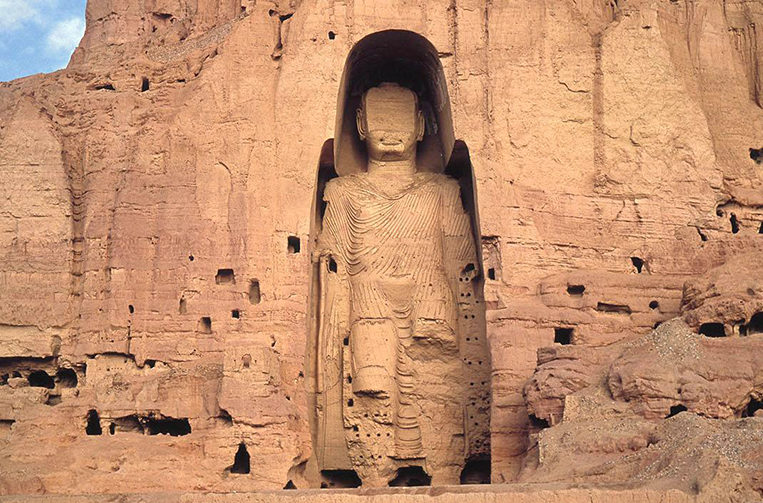

West niche, c. 6th–7th c C.E., stone, stucco, paint, Bamiyan, Afghanistan, Buddha destroyed 2001 (photo: Françoise Foliot, CC BY-SA 4.0)

More conspicuous were cave-temple complexes made by Buddhist monks and often located on sites near to major stops along the Silk Roads such as Bamiyan (in present-day Afghanistan) and the Mogao caves near Dunhuang (present-day Gansu province in China). Sometimes made up of hundreds of temples carved into cliff faces, these sites included intricately carved and painted scenes of the Historical Buddha’s life and previous lives (called jataka tales), devotional images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, as well as images of the monks and donors who may have funded the art.

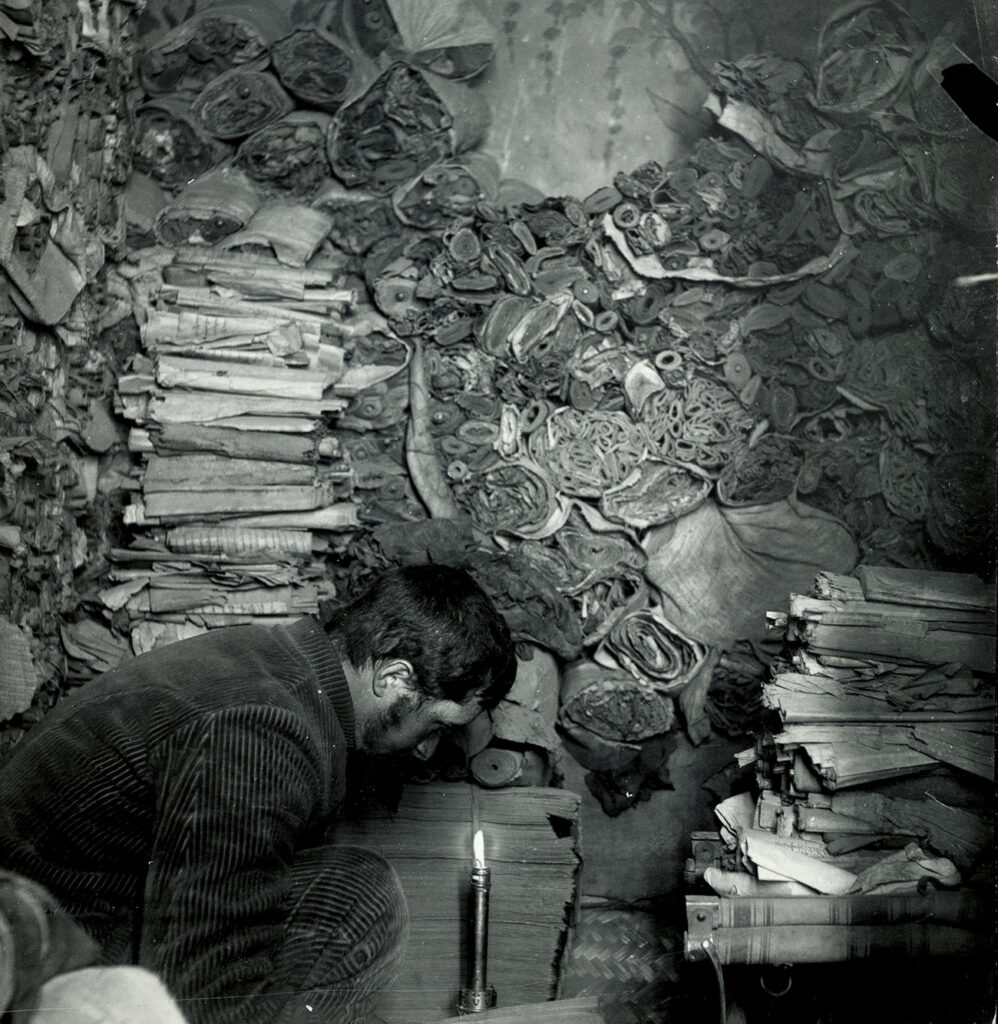

Mogao Caves 16–17 (Library Cave), Dunhuang, Gansu Province, China, 862; sealed around 1000 (photo courtesy of Dunhuang Academy)

These donors were often prominent members of local society, or in some cases, royalty. In the library cave at Mogao multilingual texts, Buddhist sutras, printed images and books, and paintings on silk and paper were also preserved, hinting at the quantity of portable objects that traveled to and from these different sites.

Buddha, Cave 20 at Yungang, Datong, China (photo: Marcin Białek, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The paintings and sculpture at these sites tell the story of different artistic traditions that came together along the Silk Roads, including inspiration from Greek art via Gandhara (in present-day north India and Pakistan). Most impressive are the monumental Buddhas found in several of the most prominent of these cave temple complexes, notably Bamiyan (tragically, the two monumental Buddhas were destroyed in 2001), Longmen, and Yungang in China.

The introduction of Buddhism into China, and then to Korea and Japan was not a smooth and linear process but took place over hundreds of years, with Buddhism falling in and out of favor over the centuries. However, during the height of the Silk Road, Buddhism enjoyed support among Chinese elites. In particular, the cave temples at Luoyang and Yungang were important sites of Chinese imperial patronage of Buddhism during the Northern dynasties period into the Tang dynasty (618–906).

Watch videos and read essays about ideas and religion along the Silk Roads

Bamiyan Buddhas: These colossal figures presided over the Bamiyan Valley for over 1000 years; the Taliban demolished them in 2001.

Read Now >

Mogao caves at Dunhuang: The ‘Caves of the Thousand Buddhas’ (Qianfodong), also known as Mogao, are a magnificent treasure trove of Buddhist art.

Read Now >

Cave 17 at Mogao: Hidden in a cave and undisturbed for centuries, this important collection of paintings was rediscovered in 1900.

Read Now >

Yungang grottoes in China: Imagine peering into a cave and seeing a monumental carved Buddha peer right back at you.

Read Now >

Longmen caves, Luoyang: This cave complex reveals how Northern Wei and early Tang rulers used Buddhist imagery to assert authority.

Read Now >/6 Completed

People along the Silk Roads

Buddhist monks were some of the most famous travelers along the Silk Road, bringing Buddhist art, scriptures, and thought with them during their journeys between India, Central Asia, China, Korea, and Japan. However, perhaps more important were the Sogdians, an Iranian people originating from present-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

Musicians from Central Asia, who were often Sogdians, were popular in ancient China. Here, they are shown seated on a camel, Tang dynasty (618–907 C.E.), glazed earthenware, China, 58.4 cm high, excavated in 1957 from the tomb of Xianyu Tinghui, general of Yunhui, buried in western suburbs of Chang’an (Xi’an), dated to 723 C.E. (National Museum of China, Beijing)

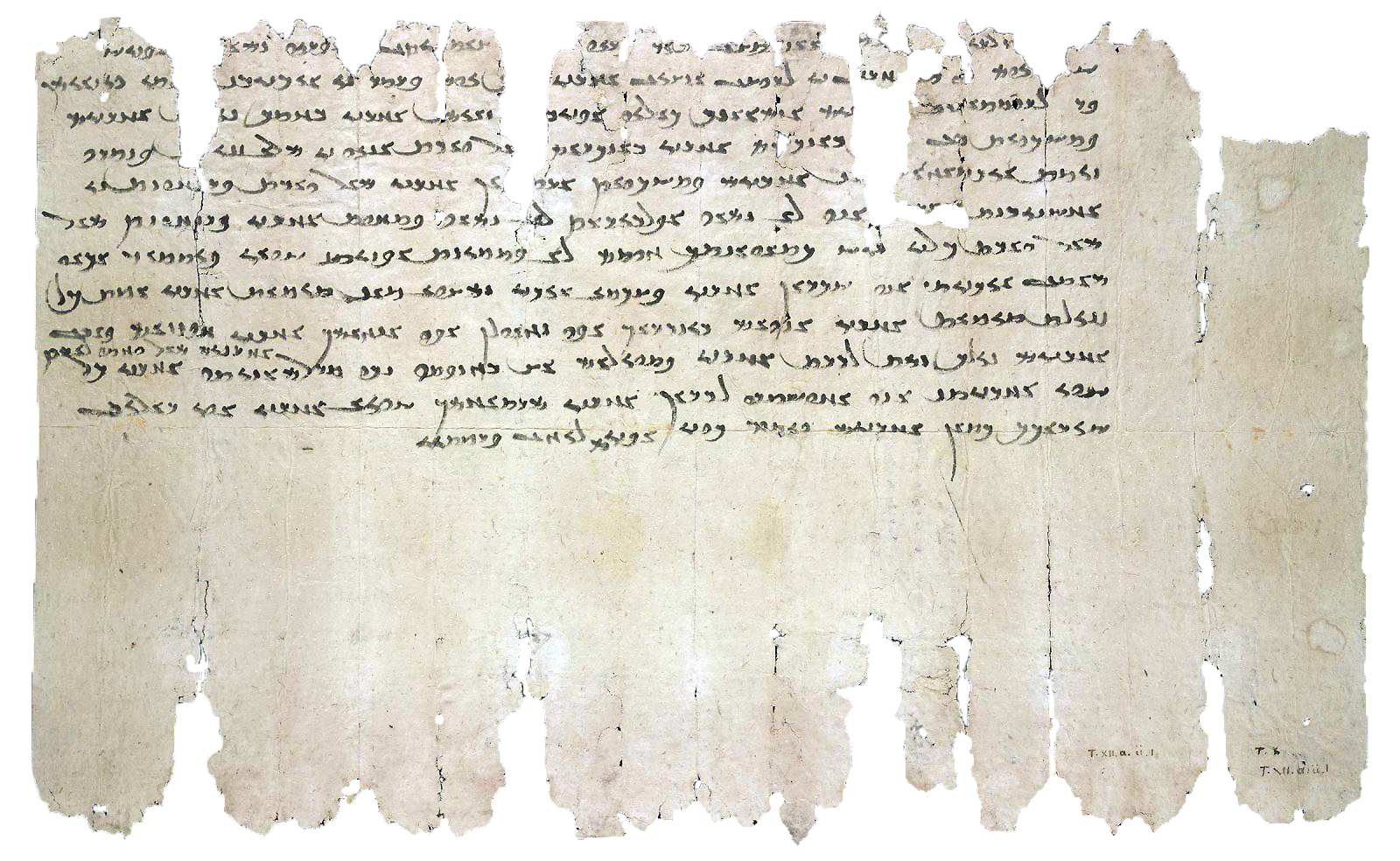

Sogdian merchants established communities across the Silk Road and served as cultural intermediaries in many of the places they lived thanks to their ability to speak many languages and connections to Sogdian communities across Asia. Much of what we know about 4th century Sogdian communities in both their homeland and in northwest China is thanks to the Sogdian ancient letters, discovered by Sir Aurel Stein in 1907 near Dunhuang. Most of the letters are written by merchants and discuss trade, but two were written by a woman, Miwnay, who was apparently abandoned by her husband in Dunhuang. Miwnay’s letters are a unique window into one woman’s experiences of the 4th-century Silk Road.

Sogdian Ancient Letter 1, 312 or 313 C.E.

[Verso] From her daughter, the free-woman Miwnay, to her d[ear] mother [Chatis].

[Recto] [From her dau]ghter, the free-woman Mi[wnay], to her dear [mother] Chatis, blessing and homage. It would be a good day for him who might [see] you healthy and at ease; and [for me] that day would be the best when we ourselves might see you in good health. I am very anxious to see you, but have no luck. I petitioned the councillor Sagharak, but the councillor says: Here there is no other relative closer to Nanai-dhat than Artivan. And I petitioned Artivan, but he says: Farnkhund . . . , and I refuse to hurry, I refuse to . . . And Farnkhund says: If your husband’s relative does not consent that you should go back to your mother, how should I take you? Wait until . . . comes; perhaps Nanai-dhat will come. I live wretchedly, without clothing, without money; I ask for a loan, but no-one consents to give me one, so I depend on charity from the priest. He said to me: If you go, I will give you a camel, and a man should go with you, and on the way I will look after you well. May he do so for me until you send me a letter!

Translation courtesy of Dr. Nicholas Sims-Williams, discovered in 1907 at Watchtower T.XII, west of Dunhuang 敦煌, Gansu Province, China

Wirkak or Shi Jun sarcophagus, 579–80, Northern Zhou dynasty, stone carvings with traces of pigment and gilding, China, Shaanxi Province (Shaanxi History Museum, Xi’an, China; photo: Gary Todd)

By the 6th century Sogdian populations had existed in China for hundreds of years, led by a sabao, an official who served as a liaison between the Sogdians and the Chinese government. The sabao named Wirkak (Shi Jun in Chinese) is one of the best known of these high level officials, thanks to the discovery of his tomb in Xi’an where he was buried with his wife. Combining Buddhist and Zoroastrian motifs with scenes from the couples’ life, the stone sarcophagus that housed the couple after their deaths is a monument to the intercultural lives of elite Sogdians along the Silk Roads.

Read an essay about people along the Silk Roads

The Wirkak (Shi Jun) Sarcophagus: Few migrants’ lives along the ancient Silk Road have been known in such detail as those of Wirkak (Shi Jun) and Wiyushi (Kang Shi).

Read Now >/1 Completed

Materials along the Silk Roads

Sogdian Ancient Letter 1, recto, 312 or 313 C.E., ink on paper, 42 x 24.3 cm, discovered in 1907 at Watchtower T.XII, west of Dunhuang 敦煌 , Gansu Province, China (photo: © The British Library Board)

The Silk Roads saw many different products pass along it including such diverse goods as medicines, spices, metalwork, ceramics, glass, paper, and textiles. The Sogdian ancient letters were written on paper, a material that was not produced outside of China before the 8th century, when it began to be produced in Central Asia. The ancient letters are an example of the material moving from China to Central Asia, although it is unclear how paper-making technology was actually transmitted to Central Asia. One theory is that Chinese prisoners taken West after the Battle of Talas in 751 (which the Islamic Abbasid empire won against the Chinese Tang empire) brought their paper-making technology, but this has been questioned by scholars. It is likely, however, that it was people moving along the Silk Roads who eventually brought paper making technology west with them.

As the name “Silk Road” implies, the textile trade was particularly important to Silk Road commerce, and silk, whose production method was kept secret in China for hundreds of years, was particularly sought after. Even after the introduction of silk making (sericulture) into Central Asia and the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire, Chinese silk was still highly desirable. Textiles served a variety of roles in pre-modern societies. For example, bolts of plain silk were used as currency and used to pay taxes both in parts of present-day China and in West Asia. Textiles can also provide us with clear examples of technological and artistic exchange over long distances. The introduction of silk making into Central Asia and eventually into the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire both have legends associated with them, wherein individuals (a Chinese princess who was married to the King of Khotan in the Central Asian case and Nestorian monks in the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) empire case) smuggled the human knowledge and the materials (silkworms and mulberry seeds) required for sericulture into new places. In other words, the spread of sericulture is another example of technological transfer that happened along the Silk Roads.

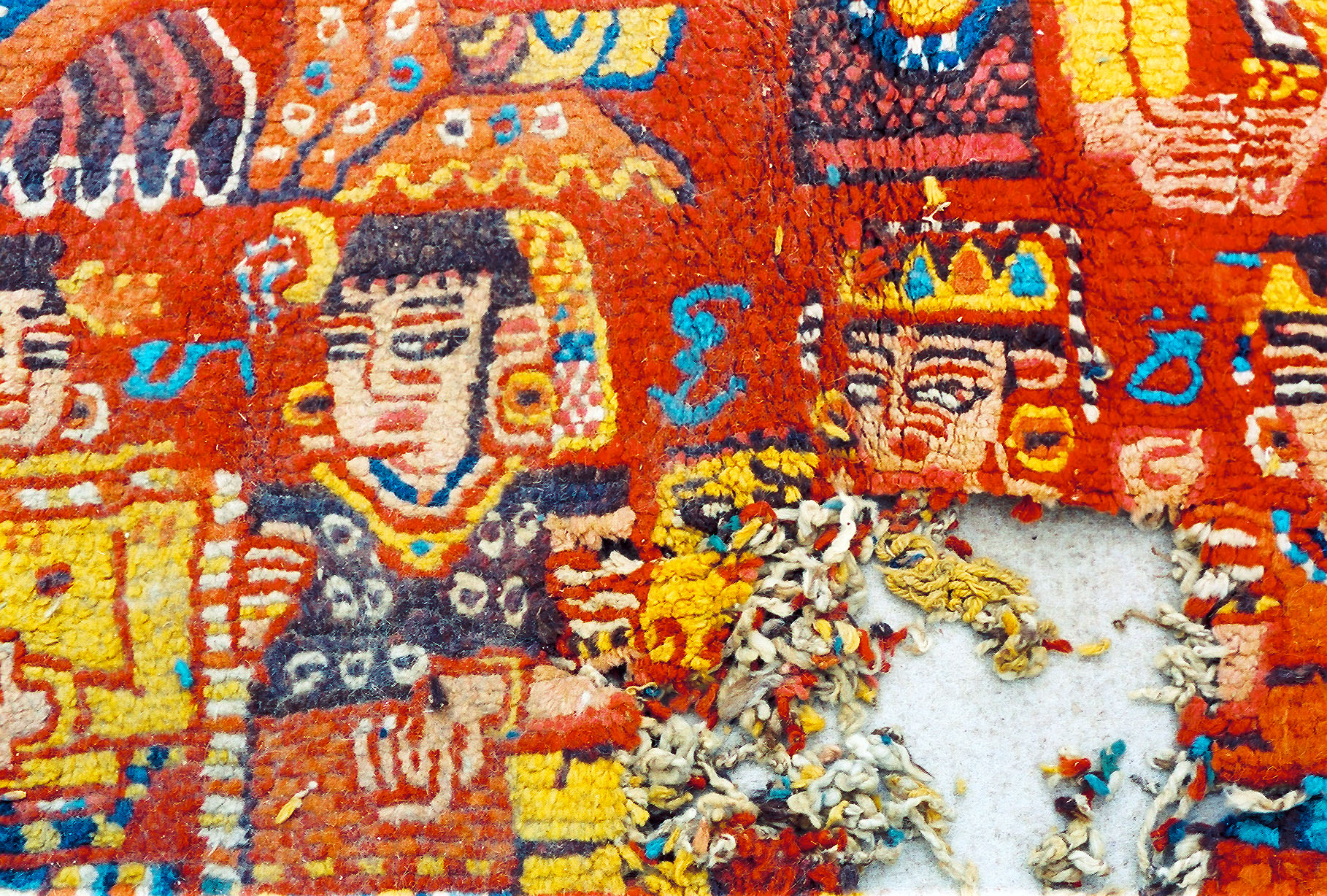

Knotted Carpet with human figures and Brahmi/Khotanese inscriptions, 5th–6th century C.E., Shanpula Township, Khotan District, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, China (photo: Qi Xiaoshan)

Artistic motifs and weave structures (ways of making textiles on the loom) also spread easily along these trade routes. Textiles were lightweight, portable, and durable, which meant they traveled easily. Weavers and other skilled artisans would also move, sometimes by choice, sometimes because of conflict or capture, along the Silk Roads as well, bringing their technology with them. A wool carpet from Khotan, in present-day Xinjiang province in China probably made in the 5th–6th century C.E. brings together religious references from Hinduism and Buddhism alongside motifs that connect to the Greco-Roman world and Bactrian artistic traditions.

Attributed to Zhou Fang (active late 8th–early 9th century), Ladies Wearing Flowers in Their Hair (detail), handscroll, ink and color on silk, 46 x 180 cm (Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang province, China)

In the Tang dynasty at the height of Silk Road exchange in China, Central Asian motifs spread by the Sogdians, such as the pearl roundel and large repeating floral rosettes, were adapted into textile decoration. Tang palace beauties were depicted in court paintings wearing textiles with repeat floral roundels, as in Zhou Fang’s Ladies with Flower in Their Hair.

Examples of rosette patterns on ceramics and metalwork. Left: footed dish with lotus medallion and cloud scrolls, first half of 8th century, Tang dynasty, earthenware with impressed decoration and three-color (sancai) lead glazes, China, 6.3 cm high, 29.5 cm in diameter (Art Institute of Chicago); right: foliated mirror with birds and floral scrolls, late 7th–early 8th century, Tang dynasty, cast bronze and applied gold plaque with repoussé, chased, and ring-punched decoration, China, 22.1 cm in diameter (Freer Gallery of Art)

Roundel or rosette patterns were adapted from textiles to a wide variety of media, including metalwork and ceramics.

Examples of textiles and other art objects with roundel motifs have been preserved in the Shōsōin treasury in Nara, Japan, one of the most important sources for elite Silk Road materials. The more than 10,000 objects from the Shōsōin collection all date to the 8th century and have been preserved since that time.

Read essays about materials along the Silk Roads

Cross-cultural artistic interaction in the Early Byzantine period: Global networks are not just a modern phenomenon.

Read Now >

A Khotanese carpet: Showcasing the cultural interaction and integration happening at the crossroads of East and Central Asia, South Asia, and China in the 5th–6th century on the ancient Silk Road.

Read Now >

A Tang silk brocade: Chinese fabrics—typically silks—were traded widely and became one of the most popular goods on the Silk Road.

Read Now >

Attributed to Zhou Fang, Ladies Wearing Flowers in Their Hair: “Beautiful women paintings” provide insight into ideals of beauty and other social customs at the Tang court.

Read Now >

The Shōsōin Repository: It held nine thousand artifacts from China, Southeast Asia, and West Asia—connecting ancient Japan to the cultural trade of the Eurasian continent.

Read Now >

Gold and jade crown: Silla tombs contained objects acquired from trade along the Silk Roads.

Read Now >/6 Completed

The products and ideas that traveled along the Silk Roads between 200 and 900 provide us with innumerable examples of exchange between different peoples at different levels of society. The best preserved materials are those kept in royal collections, like the Shōsōin in Japan or the Imperial palace collection in China, but when we read the Sogdian ancient letters or some of the documents preserved in the Library cave in Dunhuang, we remember the individuals who were impacted economically, religiously, artistically, and culturally by the Silk Roads.

Key questions to guide your reading

How did the movement of people and ideas impact artistic practices along the Silk Roads?

Alongside Buddhism, what are some of the religions we find referenced in the art of the Silk Roads?

How do textiles help us understand the spread of artistic motifs and technology along the Silk Roads?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow did the movement of people and ideas impact artistic practices along the Silk Roads?

Alongside Buddhism, what are some of the religions we find referenced in the art of the Silk Roads?

How do textiles help us understand the spread of artistic motifs and technology along the Silk Roads?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Silk Road

Sogdians

Buddhism

Buddha

Bodhisattva

Brocade

Rock-cut cave temple

Zoroastrianism

Learn more

Did You Know?: The Silk Roads Glass Trade in China and South East Asia from UNESCO

Learn more about the Sogdians

Read more about Sogdian ancient letters