Shōsōin Repository

Shōsōin Repository (photo: z tanuki, CC BY 3.0)

In the Japanese city, Nara, on the northwest rear corner of Tōdai-ji Temple’s Daibutsuden Hall stands a building largely unaltered since the 8th century. Of age-darkened cypress and deceptively plain, its distinctively ribbed walls, punctuated by large flat rectangular doors, find an echo in the linear grooves of its deeply eaved, flaring roof of ceramic tiles. Poised on forty columns and lacking stairs, its simple box shape seems to float. This vision of austere, geometric elegance is the Shōsōin Repository.

For almost 1200 years, until the twentieth century, it preserved in excellent condition approximately nine thousand artifacts from China, Southeast Asia, Iran, and the Middle East—a miscellany connecting ancient Japan to the cultural trade and artistic exchange of the Eurasian continent. While other collections worldwide hold treasures from the ancient Silk Roads, the Shōsōin is unique as a time capsule of the entire known world of its time—when Nara-period Japan glowed as a star in the brilliant cultural cosmos of Tang-dynasty China (618-907).

The Daibutsu, Vairocana, at Tōdai-ji, Nara (photo: JahnmitJa, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The structure and its context

Despite its grand spiritual setting, the Shōsōin itself is practical, and not intrinsically religious. It typifies a renowned form of storehouse called an azekura zukuri, developed by ancient Japanese village carpenters to hold grain and other foodstuffs that formed the lifeblood of their agrarian society. Often referred to as of “log cabin style,” this two thousand-year-old design is not the primitive, drafty pile the expression typically calls to mind. Nor is it simply a matter of taste. Its appearance owes to sophisticated structural engineering that makes brilliant use of wood’s basic property to expand and contract according to weather conditions. The precisely planed, triangular logs interlock to form a flat wall on the interior and the uniquely ribbed exterior.

The ceramic tiles and hip-and-gable design of the roof both shed water and repel fire. The columns that raise it from the ground stand on natural stone. In all, this creates a natural climate regulation system that lessens the dampness of Japan’s humid climate, and discourages infestation by vermin. The absence of permanent stairs deters thieves. The wooden chests in which most of the objects were kept provided additional protection, preventing light and pollution from damaging the organic materials. The secure, ventilated conditions proved ideal for protecting the prized possessions of Japan’s Buddhist monastic communities. The Shōsōin is the oldest extant example of such treasure houses.

Azekura zukuri interlocking technique (photo: ignis, CC BY-SA 2.5)

The Shōsōin interior contains three rooms on two floors, each with an entrance door. Despite the lack of written sources confirming its dating, a recent analysis of the timbers has confirmed a middle-8th century construction date (note that the middle room walls with additional flat beams that are different from those of the other two, is likely not original). Restorations done during the much later Edo period (1603 – 1868), including iron strips added to the columns and copper plates added to protect the floor edging, do not significantly impact the repository.

Objects as Buddhist offerings

Founded by early emperors, Tōdai-ji was one Japan’s highest-ranking Buddhist monastic communities and remains an important religious center. Patronage from members of imperial and noble families, as acts of piety, made it among the wealthiest. The Shōsōin mainly served to house personal possessions donated by Empress Kōmyō to the Daibutsu Vairocana, a Buddha that is the world’s largest cast-bronze statue. These gifts were made after the death of her husband, Emperor Shōmu in 756, in order to ensure the protection of his soul. These offerings were stored in the Northern room.

Senior monks used the Middle and Southern rooms for ceremonial objects, and in the 10th century, articles and documents were added from another smaller repository nearby. While the Southern room remained accessible until the Meiji period (1868-1912), sometime in the 12th century, Japan’s Imperial household sealed the Middle and Northern rooms. High-ranking ministers took responsibility for their security. From this point on the Shōsōin was rarely opened and over the centuries it survived both war and fire, leaving virtually all the ancient cultural treasures intact.

The treasure at the Shōsōin Repository

The thousands of items preserved in the Shōsōin repository include manuscripts, musical instruments, textiles, shoes, banners, ceramics and glass, metalwork, and lacquerware. These objects showcase the high level of craftsmanship and the complex techniques available to the imperial household during this early period, some of which are now lost.

We also benefit from the meticulous records of these objects kept by ancient caretakers. Thanks to an inscription on each, today we know its date, usage, and sometimes its provenance—all of which help to put the objects in context. The material preserved in the repository is particularly important because it created the foundation for the Japanese art and style that followed, which originated in this era against the backdrop of China’s Tang Dynasty (which has long been seen as a golden age of art, music, and literature, and economic and political influence across East Asia). Nara was modeled after Chang’an (now Xi’an in China) the Tang capital, and a self-proclaimed center of Buddhism. It was especially between the 7th and 8th centuries that Japan, welcoming foreign people and sending envoys abroad, studied, preserved, and developed its own artistic culture.

Silk Roads

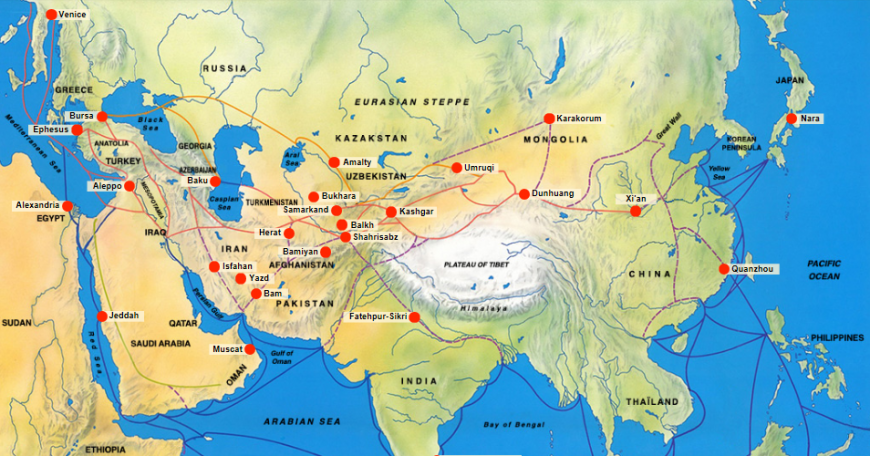

The unquestionable beauty and finesse of the mulberry wood lute inlaid with mother of pearl makes evident Tang China’s wide, complex cultural impact. Known in Japan as a Kuwanoki no genia and in China as a pipa, this pear-shaped 5-string instrument was likely introduced originally to China from Central Asia in the 1st or 2nd century C.E., and would attain a lasting popularity. This particular 8th century example from the Shōsōin very much recalls the type of pipa depicted on murals of the 3rd-4th century Buddhist cave complexes of Dunhuang and Yulin in what is now Gansu Province, China—vestiges of a chain of major monastic centers that once spread Buddhism and served as junctions for the interchange of ideas, goods and peoples along the northern Silk Roads.

Kuwanoki no genia (a composite image showing front and back), Tang Dynasty, 8th century, (Shōsōin Repository, Nara) (front and back)

Far east across the Yellow Sea, the Sea of Japan, and the ancient kingdoms of the Korean peninsula, the route concluded with the imperial monasteries of Nara-era Japan, including Tōdai-ji.

The large floral motif embellishing the Kuwanoki no genia and other objects in the repository, such as mirrors, boxes, and ritual rugs offer further links. Typical of the late Tang period, this motif is generally recognized as an emblem of the Tang dynasty; and in Japan it is known as kara-hana, meaning “Tang flower.”

Musicians (pipa at the bottom right and held by the central dancing character behind the shoulders) from the Western Paradise of Amitaba, Dunhuang Cave 112, Middle Tang Period, 8th century

Sasanian influence

Correspondence with visual material from these Chinese caves confirms that many objects in the Shōsōin enjoyed actual use. The repository artifacts likewise make very tangible the Silk Route’s far-flung connections and the complexities. For example, a handsome glass bowl with cut hollow facets finds an echo in a 9th century banner discovered in the Mogao caves at Dunhuang.

Left: Hakururi no wan from the Shōsōin Repository; right: Banner (detail) of a Bodhisattva holding a glass (British Museum)

The banner portrays an important deity, a Bodhisattva, holding a similar bowl his hand (in Japanese the bowl is called a Hakururi no wan). This type of glass is commonly known as “Sasanian glass,” referring to the last pre-Islamic Iranian dynasty that, from the 3rd to the 7th century, dominated a vast Eurasia territory (from Central Asia to Iraq). But this type of glass was already being produced before the Sasanian period, and also elsewhere in the Middle East. A similar, much earlier type also was discovered in Palmyra (in modern Syria).

Ancient fabrics were among the most highly prized of luxury items in ancient times and represent the majority of the artifacts from the Shōsōin. Similar patterned textiles remain among the important possessions of other Buddhist communities established during the era of imperial Nara (such as Hōryū-ji). Almost entirely made of silk and ramie, they belong to the second period of textile development in Japan, which like other items in the Shōsōin, reflect Tang China’s influence in their motifs, such as the floral medallion made in weft-faced compounds (generally known in the West as samite). An earlier, first phase can be dated to between the 4th or 5th centuries, possibly when early emperors invited textile weavers to Japan from Korean kingdoms and China, societies that were then far more sophisticated.

Reproduction of a silk twill textile, woven in Japan, imitating a Sasanian Persian original, from the Shōsōin repository in Nara (originally held in Horyuji Temple), 6th–7th century (private collection)

In particular, a clan of artisans called the Nishiki is mentioned in early Japanese historical accounts, most famously “A Record of Ancient Things” (Kojiki) and “Chronicles of Japan” (Nihon Shoki). Not by coincidence, the term nishiki has long referred to Japanese polychrome patterned weavings.

Amongst the Iranian or Iranian-inspired artifacts in Nara, there is a particular nishiki fragment, now considered a national treasure, which shows the artistic collaboration among a diverse group of artisans of different ethnic groups who combined their artistic and technical expertise. Its design consists of a repetition of beaded roundels enclosing pairs of mirrored hunters on a winged horse, drawing a bow at a rearing lion. All the pictorial elements in the composition (crown, roundel, flower, etc.) link to Sasanian motifs, though the Chinese characters in the bodies of the horses suggest possible Chinese-Central Asian production. Such collaborations were quite frequent along the Silk Road, especially in the area between Sogdiana (a colony of the Eastern Sasanian Empire) and Turfan in the Xinjiang Province. The composition often appears on Sasanian metalwork in collections worldwide.

Today

In 1997, the Shōsōin building was designated as a National Treasure and registered as part of the World Heritage. Its contents are no longer kept there but in two secure buildings built nearby in 1953 and 1962, called the Eastern and the Western Repository. Every autumn, for about two weeks, fifty to sixty items are exhibited in the Nara National Museum (with a related catalog), giving the public the opportunity to admire and learn about many of the Buddhist-inspired artifacts preserved by the Shōsōin that characterize the “Nara period.” The Shōsōin’s treasure as a whole represents the cultural transfers that occurred along the Silk Road, which stretched in the East through China and Korea, and placed Japan in an ancient global context.

Additional resources:

History of Shōsōin from the Imperial Household Agency

Collections of Persian Art in Japan

Complete list of SHOSOIN Collection solid objects ‘Shosoin Tanabetu MOKUROKU’, Nara, Japan

Japan’s Oldest Archive: A Workshop on the Shosoin

Traveling the Silk Road from the American Museum of Natural History

Ry-Oichi Hayashi. The Silk Road and the Shoso-In (The Heibonsha Survey of Japanese Art ; V. 6. Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing, 1980).

Kaneo Matsumoto, Jōdai –Gire: 7th and 8th Century Textiles in Japan from the Shōsō-in and Hōryū-ji (Kyoto: Shikosha Publishing Co. Ltd., 1984).