Mogao Caves (photo: 慕尼黑啤酒 , CC BY-SA 3.0)

A trove of Buddhist art

The ‘Caves of the Thousand Buddhas’ (Qianfodong), also known as Mogao, are a magnificent treasure trove of Buddhist art. They are located in the desert, about 15 miles south-east of the town of Dunhuang in north western China. By the late fourth century, the area had become a busy desert crossroads on the caravan routes of the Silk Road linking China and the West. Traders, pilgrims, and other travelers stopped at the oasis town to secure provisions, pray for the journey ahead or give thanks for their survival. Records state that in 366 monks carved the first caves into the cliff stretching about 1 mile along the Daquan River.

An archive rediscovered

At some point in the early eleventh century, an incredible archive—with up to 50,000 documents, hundreds of paintings, together with textiles and other artefacts—had been sealed up in a chamber adjacent to one of the caves (Cave 17). Its entrance was concealed behind a wall painting and the trove remained hidden from sight for centuries. In 1900, it was discovered by Wang Yuanlu, a Daoist monk who had appointed himself abbot and guardian of the cave-temples. The first Western expedition to reach Dunhuang arrived in 1879. More than twenty years later Hungarian-born Marc Aurel Stein, a British archaeologist and explorer, learned of the importance of the caves.

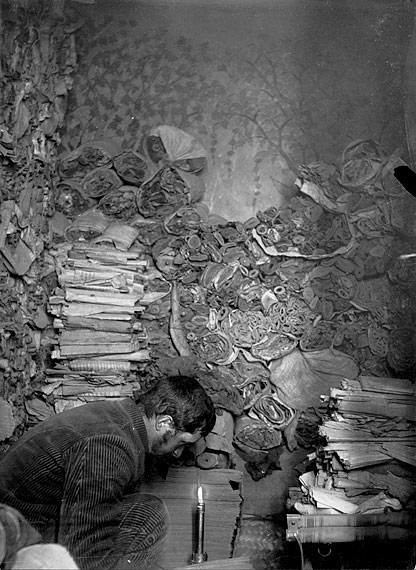

Paul Pelliot working in the library cave in 1908 (photo: Bahatur)

Stein reached Dunhuang in 1907. He had heard rumors of the walled-in cave and its contents. The abbot sold Stein seven thousand complete manuscripts and six thousand fragments, as well as several cases loaded with paintings, embroideries and other artifacts. French explorer Paul Pelliot followed close on Stein’s heels. Pelliot remarked in a letter, “During the first ten days I attacked nearly a thousand scrolls a day….”

Other expeditions followed and returned with many manuscripts and paintings. The result is that the Dunhuang manuscripts and scroll paintings are now scattered over the globe. The bulk of the material can be found in Beijing, London, Delhi, Paris, and Saint Petersburg. Studies based on the textual material found at Dunhuang have provided a better understanding of the extraordinary cross-fertilization of cultures and religions that occurred from the fourth through the fourteenth centuries.

A thousand years of art

There are about 492 extant cave-temples ranging in date from the fifth to the thirteenth centuries. During the thousand years of artistic activity at Dunhuang, the style of the wall paintings and sculptures changed. The early caves show greater Indian and Western influence, while during the Tang dynasty (618–906 C.E.) the influence of the Chinese painting styles of the imperial court is apparent. During the tenth century, Dunhuang became more isolated and the organization of a local painting academy led to mass production of paintings with a unique style.

Mural, Cave-temple 257, Dunhuang, Gansu Province (photo: Ismoon, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The cave-temples are all human-made, and the decoration of each appears to have been conceived and executed as a conceptual whole. The wall-paintings were done in dry fresco. The walls were prepared with a mixture of mud, straw, and reeds that were covered with a lime paste. The sculptures are constructed with a wooden armature, straw, reeds, and plaster. The colors in the paintings and on the sculptures were done with mineral pigments as well as gold and silver leaf. All the Dunhuang caves face east.

Changes in belief

The art also reflects the changes in religious belief and ritual at the pilgrim site. In the early caves, jataka tales (previous lives of the Historical Buddha) were commonly depicted. During the Tang dynasty, Pure Land Buddhism became very popular. This promoted the Buddha Amitabha, who helped the believer achieve rebirth in his Western Paradise, where even sinners are permitted, sitting within closed lotus buds listening to the heavenly sounds and the sermon of the Buddha, thus purifying them. Various Paradise paintings decorate the walls of the cave-temples of this period, each representing the realm of a different Buddha. Their Paradises are depicted as sumptuous Chinese palace settings.

Western Paradise, Cave-temple 172, Tang dynasty, Dunhuang, Gansu province

Images of the caves

During WWII the famous, contemporary Chinese painter Zhang Daqian spent time at Dunhuang with his students. They copied the cave paintings. Photojournalist James Lo—a friend of Zhang Daqian—joined him at Dunhuang and systematically photographed the caves. Traveling partly on horseback, they arrived at Dunhuang in 1943 and began a photographic campaign that continued for eighteen months. The Lo Archive (a set is now housed at Princeton University) consists of about 2,500 black-and-white historic photographs. Since no electricity was available, James Lo devised a system of mirrors and cloth screens that bounced light along the corridors of the caves to illuminate the paintings and sculptures.

Today the Mogao cave-temples of Dunhuang are a World Heritage Site. Under a collaborative agreement with China’s State Administration of Cultural Heritage (SACH), the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) has been working with the Dunhuang Academy since 1989 on conservation. Tourists can visit selected cave-temples with a guide.

Backstory

The Mogao caves at Dunhuang were reclaimed from the encroaching Gobi desert beginning in the early twentieth century, but their conservation is an ongoing challenge. In addition to natural threats like sandstorms and rainwater, the caves’ delicate murals face damage caused mainly by tourists (hundreds of thousands per year, up to 6,000 per day), whose presence adds dangerous levels of carbon dioxide and humidity to the air. Fortunately, much is being done to preserve the artworks at Dunhuang—and new technologies are also making it possible for the caves to be meticulously documented and shared around the world.

The Mogao caves were designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1987, and are overseen by international watchdog groups as well as a state-run institution called the Dunhuang Research Academy. Since 1989, they have been working with China’s State Administration of Cultural Heritage and the Getty Conservation Institute on structural reinforcement, careful restoration and stabilization of the murals, and digital documentation. The Mogao caves were also a test site for the development of the China Principles, a set of international standards for preserving cultural heritage—not only in terms of physical assets, but also with respect to local traditions, environment, and history.

Images of the caves were first produced during World War II, when the famous contemporary Chinese painter Zhang Daqian spent time copying the cave paintings with his students. Photojournalist James Lo joined the effort by systematically photographing the caves using an ingenious system of mirrors to bounce natural light into the dark spaces. The Lo Archive (a set is now housed at Princeton University) consists of about 2,500 black-and-white photographs.

In recent years, teams have been working to create physical replicas of the caves that can be displayed at museums and other sites around the world. Virtual reality technology has also been used to create immersive media environments that replicate the experience of being in the caves, and preserve important data about the spaces’ measurements and other physical properties. These types of reproductions can also help reduce the effects of human presence in the caves by making digital reconstructions available at Dunhuang itself: visitors can spend time looking closely at these “digital caves,” allowing for stricter time limits and lower visitor numbers in the caves themselves. In addition, these digital versions can be shared easily around the world, along with a growing archive of high-quality photographs. The manuscripts and other objects from Cave 17, discussed above, have also been digitized and are available online.

New technologies are also making it possible to preserve and share data about other important Buddhist sites in China. At the Yungang Grottoes in northeastern China, where the sculpture is threatened not only by tourism but also by China’s high levels of industrial air pollution and acid rain, 3-D scanning is being used to model the monumental sculptures and create highly accurate reproductions that can be shared and shown around the globe.

The Mogao caves and Yungang Grottoes are outstanding human achievements that are now threatened by other types of human endeavors: climate change, tourism, and pollution. The continued development of new technologies and approaches for preserving and documenting these invaluable sites is essential to their survival.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee