Buddhism in China

Buddhism probably arrived in China during the Han dynasty (206 B.C.E. – 220 C.E.), and became a central feature of Chinese culture during the period of division that followed. Buddhist teaching ascribed great merit to the reproduction of images of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, in which the artisans had to follow strict rules of iconography.

A twelfth-century catalogue of the Chinese imperial painting collection lists Daoist and Buddhist works from the time of Gu Kaizhi (c. 344-406 C.E.) onwards. However, no paintings by major artists of this period have survived, because foreign religions were proscribed between 842 and 845, and many Buddhist monuments and works of art were destroyed.

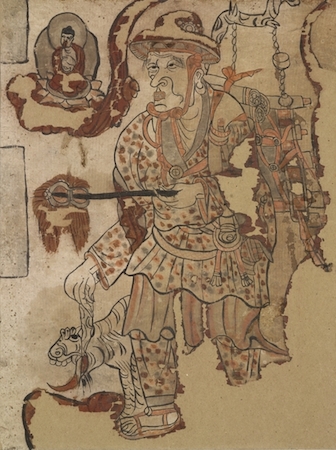

Traveling monk, 10th century, Five Dynasties or Northern Song Dynasty, wearing a hat, holding a fan and accompanied by a tiger, ink and colors on paper, from Cave 17, Mogao, near Dunhuang, Gansu province, China © Trustees of the British Museum. The little Buddha supported by a cloud may be there to protect him, and has been identified as Prabhutaratna (a Buddha of the past).

The Valley of the Thousand Buddhas

What has survived from the Tang period (618-906) is an important collection of Buddhist paintings on silk and paper, found in Cave 17, in the Valley of the Thousand Buddhas at the Chinese end of the Silk Road. Since Dunhuang was under Tibetan occupation at this time, its cave shrines and paintings escaped destruction.

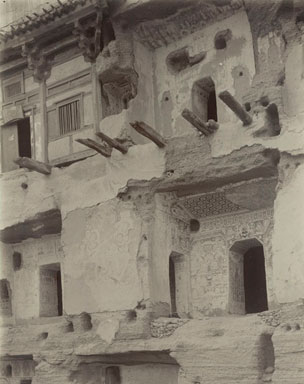

The “Caves of the Thousand Buddhas,” or Qianfodong, are situated at Mogao, about 25 kilometres south-east of the oasis town of Dunhuang in Gansu province, western China, in the middle of the desert. By the late fourth century, the area had become a busy desert crossroads on the caravan routes of the Silk Road linking China and the West. Traders, pilgrims and other travelers stopped at the oasis town to stock up with provisions, pray for the journey ahead or give thanks for their survival. At about this time wandering monks carved the first caves into the long cliff stretching almost 2 kilometers in length along the Daquan River.

Over the next millennium more than 1000 caves of varying sizes were dug. Around five hundred of these were decorated as cave temples, carved from the gravel conglomerate of the escarpment. This material was not suitable for sculpture, as at other famous Buddhist cave temples at Yungang and Longmen. The Caves of the Thousand Buddhas gained their name from the legend of a monk who dreamt he saw a cloud with a thousand Buddhas floating over the valley.

Sealed for a thousand years, then rediscovered

Photograph of Dunhuang

When the Silk Road was abandoned under the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), oasis towns lost their importance and many were deserted. Although the Mogao caves were not completely abandoned, by the nineteenth century they were largely forgotten, with only a few monks staying at the site. Unknown to them, at some point in the early eleventh century, an incredible archive—with up to 50,000 documents, hundreds of paintings, together with textiles and other artifacts—was sealed up in one of the caves (Cave 17). Its entrance concealed behind a wall painting, the cave remained hidden from sight for centuries, until 1900, when it was discovered by Wang Yuanlu, a Daoist monk who had appointed himself abbot and guardian of the caves.

The first Western expedition to reach Dunhuang, led by a Hungarian count, arrived in 1879. More than twenty years later one of its members, Lajos Lóczy, drew the attention of the Hungarian-born Marc Aurel Stein, by then a well-known British archaeologist and explorer, to the importance of the caves. Stein reached Dunhuang and Mogao in 1907 during his second expedition to Central Asia. By this time, he had heard rumors of the walled-in cave and its contents.

After delicate negotiations with Wang Yuanlu, Stein negotiated access to the cave. “Heaped up in layers,” Stein wrote, “but without any order, there appeared in the dim light of the priest’s little lamp a solid mass of manuscript bundles rising to a height of nearly ten feet…. Not in the driest soil could relics of a ruined site have so completely escaped injury as they had here in a carefully selected rock chamber, where, hidden behind a brick wall, …. these masses of manuscripts had lain undisturbed for centuries.” (M. Aurel Stein,Ruins of Desert Cathay (1912; reprint, New York, Dover, 1987).

The abbot eventually sold Stein seven thousand complete manuscripts and six thousand fragments, as well as several cases loaded with paintings, embroideries and other artifacts; the money was used to fund restoration work at the caves.The manuscripts are now in the British Library and the paintings have been divided between the National Museum in New Delhi and the British Museum, where over three hundred paintings on silk, hemp and paper are kept.

Bodhisattva as Guide of Souls, early 10th century, Five Dynasties, ink and colors on a silk banner, from Cave 17, Mogao, near Dunhuang, Gansu province, China © Trustees of the British Museum

This painting is inscribed with the characters yinlu pu or “Bodhisattva leading the Way.” It is one of several examples from Mogao of a bodhisattva leading the beautifully clad donor figure to the Pure Land, or Paradise, indicated by a Chinese building floating on clouds in the top left corner. The two figures are also supported by a cloud indicating that they are flying.

The bodhisattva, shown much larger than the donor, is holding a censer and a banner in his hand. The banner is one of many of the same type found at Mogao, with a triangular headpiece and streamers. The woman appears to be very wealthy, with gold hairpins in her hair. Actual examples of these were found in Chinese tombs. Her fashionably plump figure suggests that the painting was executed in the ninth or tenth century.

Suggested readings:

H. Wang (ed.), Sir Aurel Stein. Proceedings of the British Museum Study Day 2002 (London, British Museum Occasional Paper 142, 2004).

H. Wang, Money on the Silk Road. The Evidence from Eastern Central Asiato c. AD 800 (London, British Museum Press, 2004).

S. Whitfield, Aurel Stein on the Silk Road (London, British Museum Press, 2004).

J. Falconer, A. Kelecsenyi, A. Karteszi and L. Russell-Smith (E. Apor and H. Wang eds.), Catalogue of the Collections of Sir Aurel Stein in the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (published jointly by the British Museum and the Library of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest [LHAS Oriental Series 11], 2002).

H. Wang (ed.), Handbook to the Stein Collections in the UK (London, British Museum Occasional Paper 129, 1999).

© Trustees of the British Museum