The Viceroyalty of New Spain: an overview

Read Now >Chapter 50

The art of the viceroyalty of New Spain

Saint John the Evangelist, 17th century, feather mosaic and paper on copper (Collection of Daniel Liebsohn, loaned to Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City)

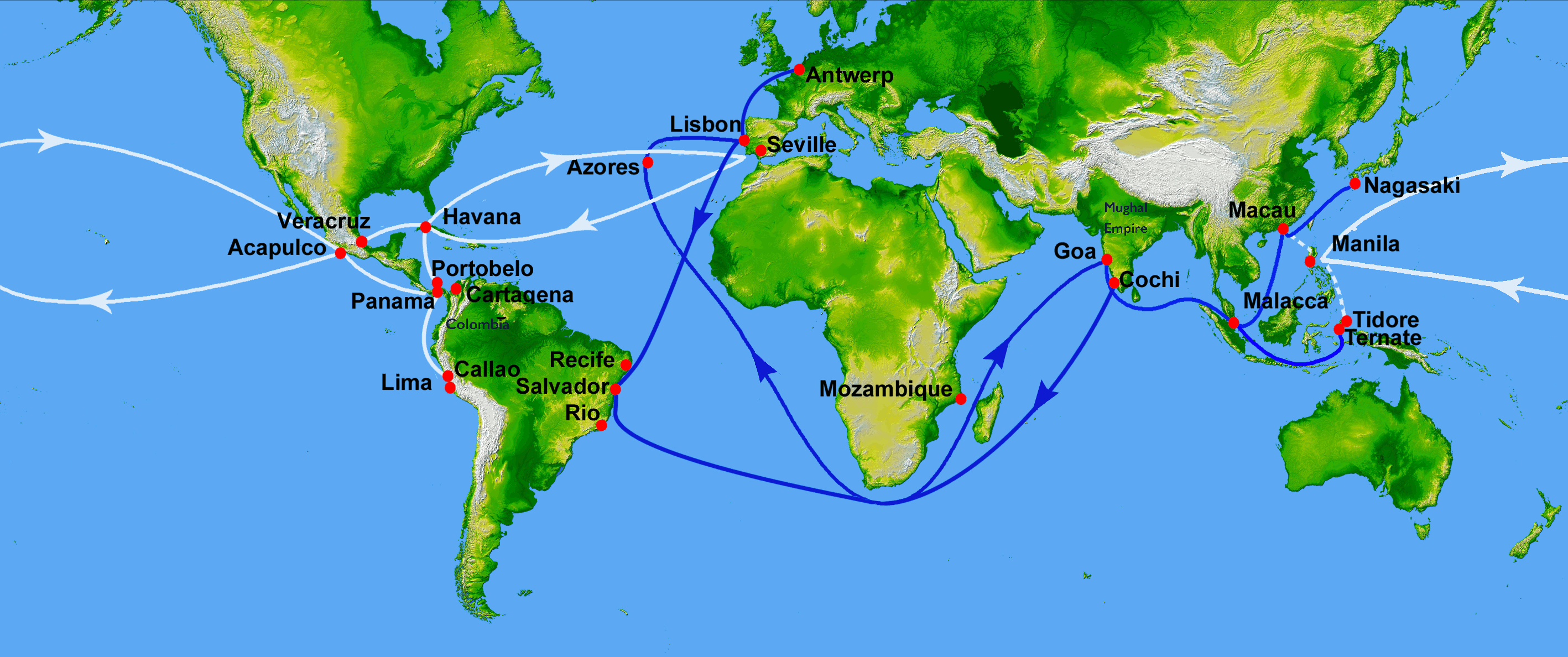

Today when we think of globalization we may picture the ability to click “buy” and have goods produced half a world away at our doorstep within days or the cornucopia of world cuisines encountered when walking in a city. We tend to think of globalization—the ways that technology and trade have made our world more interconnected—as something new. But let’s take a step back and think about an earlier globalized world.

Map with global trade routes, c. 1600

In the late 15th and 16th centuries, the world experienced a boom of globalization unrivaled by any earlier human exchanges. Between the 15th and 17th centuries, European explorers traveled the world seeking trade, wealth, and knowledge. As a result a new global age was born with four of the world continents—Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas—in contact with each other for the first time. This history was fraught. Europeans not only explored, they also colonized and plundered. The early modern age was born of violence and greed as societies as far flung as Mexico, the Philippines, and Congo were violently and inextricably altered. It is important for us to probe this fraught history, and it is also useful to think of the resistance, hybridization, and cultural exchanges that occurred as a result. That is, the colonized did not passively accept the realities of colonization—nor did the colonizers themselves remain unchanged. The so-called age of exploration, also known as the early modern period, is so known today because it birthed our modern, interconnected, and globalized world.

Map of the Viceroyalty of New Spain c. 1800.

This chapter explores that phenomenon as it played out specifically in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which encompassed parts of the Southwestern United States, Mexico, and much of Central America. The Philippines, likewise colonized by Spain, were also part of the enormous reach of the Viceroyalty that became a central player in the globalized Spanish world alongside the Viceroyalty of Peru.

The objects explored in this chapter originate in, were exported to, and/or depict peoples originating in New Spain, showcasing the remarkable fluorescence of the visual arts that occurred at the crux of a multi-ethnic trans-oceanic encounter. In the mid-eighteenth century a Jesuit chronicler described the global reach of New Spain by referring to Mexico as an “archive of the world,” describing objects that crossed “two oceans” to link Europe, Asia, and Africa with the Americas. [1] This extraordinary global reach was the byproduct of exploration and colonization, which while violent, produced a rich and diverse material world. Sifting through the visual archive leads us to a greater understanding of the global early modern world of which Mexico played a key role.

Watch a video about New Spain

/1 Completed

The Visual Culture of Conquest

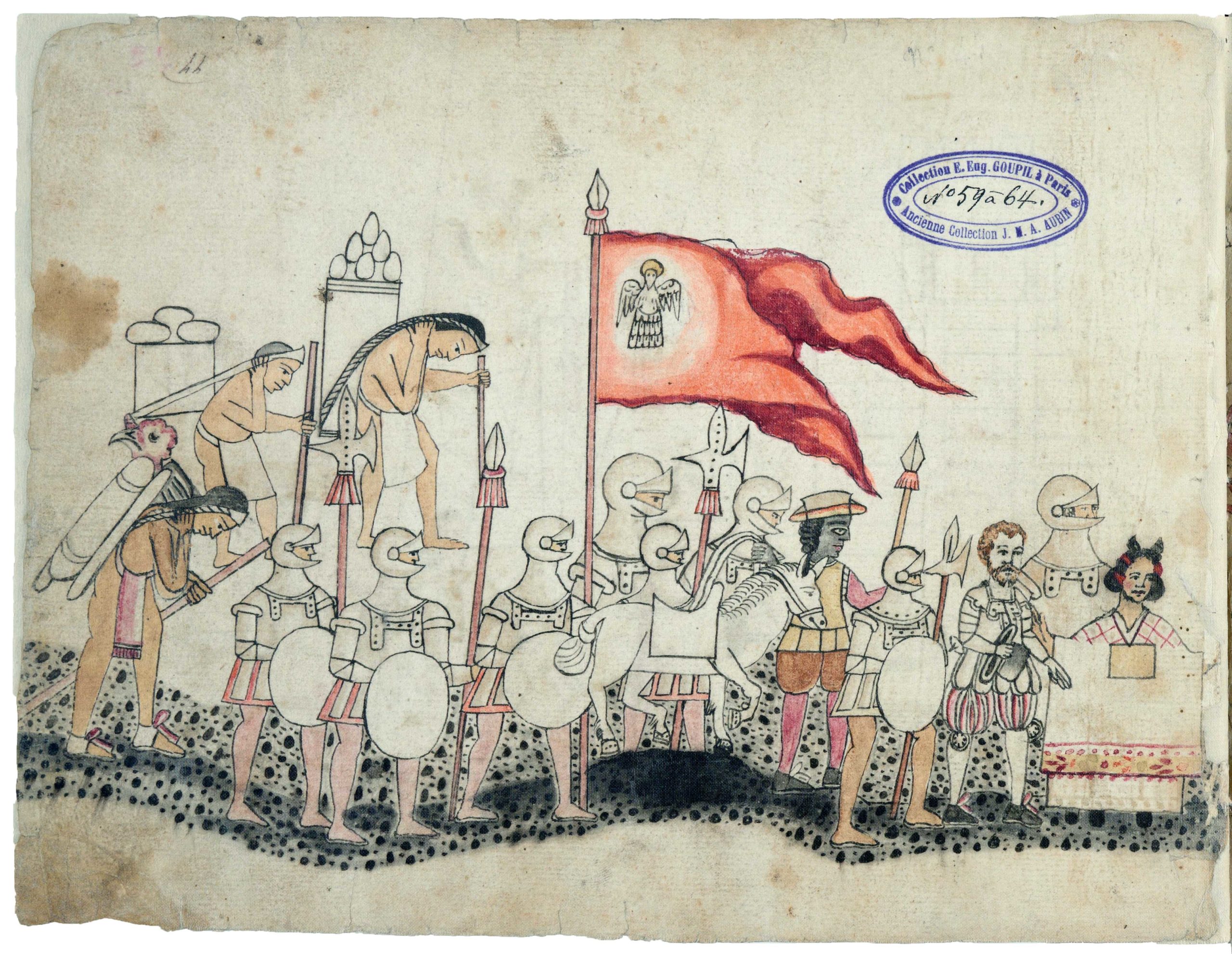

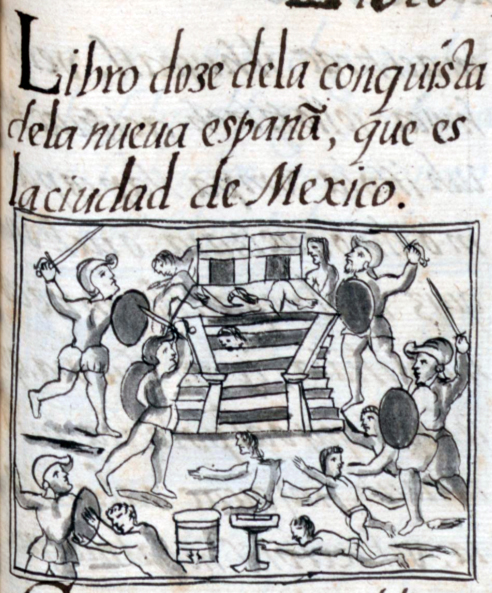

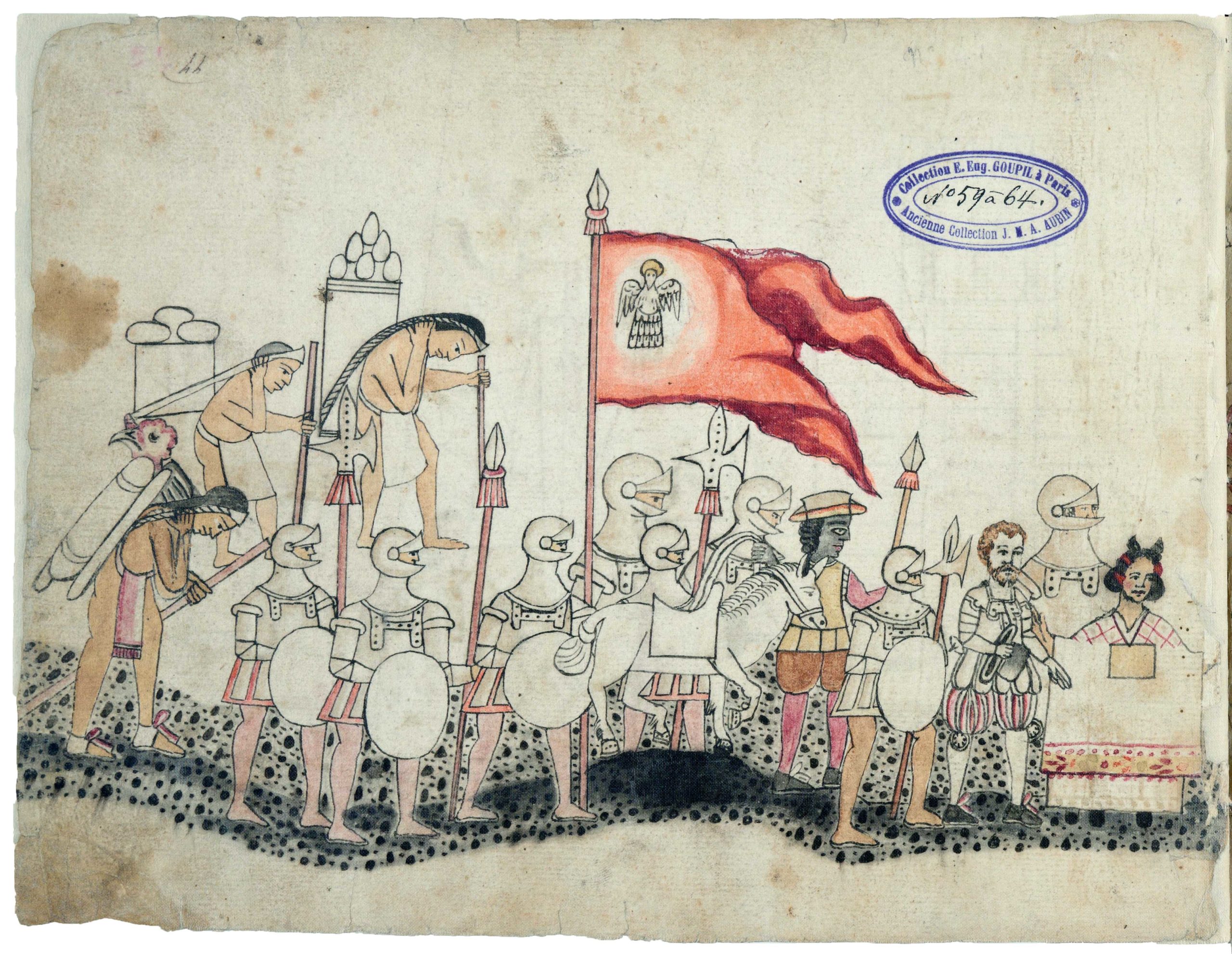

Codex Azcatitlan, c. 1530, 21 x 28 cm (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

Much of the Viceroyalty of New Spain lies within Mesoamerica which was home to the earliest large scale civilizations in the Americas. The Mexica (now commonly known as Aztecs), founded in the early fourteenth century what would become a massive empire over the next 200 years. As the Aztec empire expanded, across the Atlantic and a world away, European explorers began searching for sea routes to Asia to bypass the overland and sea routes that were costly to traverse due to the power of the Ottoman Empire. Most famously, Christopher Columbus, a navigator from Genoa, was commissioned by the Spanish crown to sail west in search of Asia. Instead he accidentally landed in the Americas, coming across the fringes of the vast Mexica empire. It was not until 1519 that another explorer named Hernán Cortés first made contact with the Mexica after sailing from Cuba without any official authorization.

Illustration of the the meeting of Hernán Cortés and Moctezuma II, from Diego Durán, The History of the Indies of New Spain, 1579 (Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid)

This meeting between Spaniards and the Mexica is illustrated in fascinating manuscripts painted by Indigenous artist-scribes (called tlacuiloque), such as those seen in the Codex Azcatitlan and Codex Durán. The images of the initial encounter showcase the multi-racial and multi-ethnic reality of the Spanish conquest. Conquistadors from Spain came from various parts of the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal), and even included people of African descent.

The Indigenous peoples of the Americas who encountered Spaniards during the first conquests were from many different linguistic and ethnic groups, including not only the Mexica, but other ethnic groups such as the Tlaxcalteca who were enemies of the Mexica and had allied themselves with the Spaniards.

The majestic Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan was an important target of Spaniards in the early conquest, as Cortés was intent on subduing the powerful empire. When Spaniards arrived in Tenochtitlan, they were utterly amazed by its size and splendor. Bernal Díaz del Castillo, who was a soldier in Cortés’s militia, wrote decades later about his initial impressions of the city:

When we saw so many cities and villages built both on the water and on dry land, and this straight, level causeway, we couldn’t resist our admiration. It was like the enchantments in the book of Amadís, because of the high towers, pyramids, and other buildings, all of masonry, which rose from the water. Some of our soldiers asked if what we saw was not a dream.Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The True History of the Conquest of New Spain, not published until1568

The Spaniards were amazed by the Mexica’s monumental architecture, infrastructure, and advanced city planning seen in the island-city capital, which they nevertheless went on to raze and reconstruct in a European style as a statement of their power and dominance.

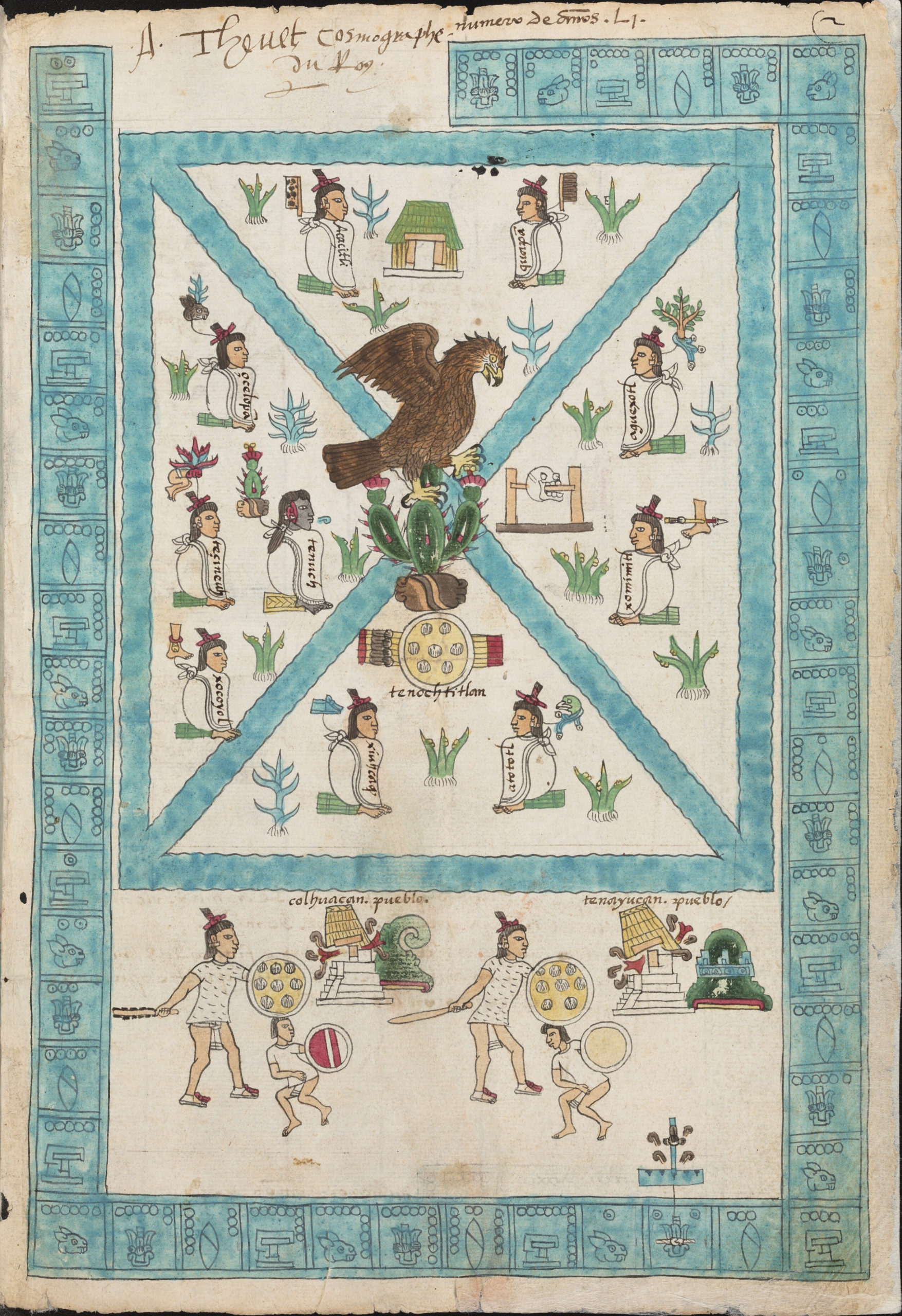

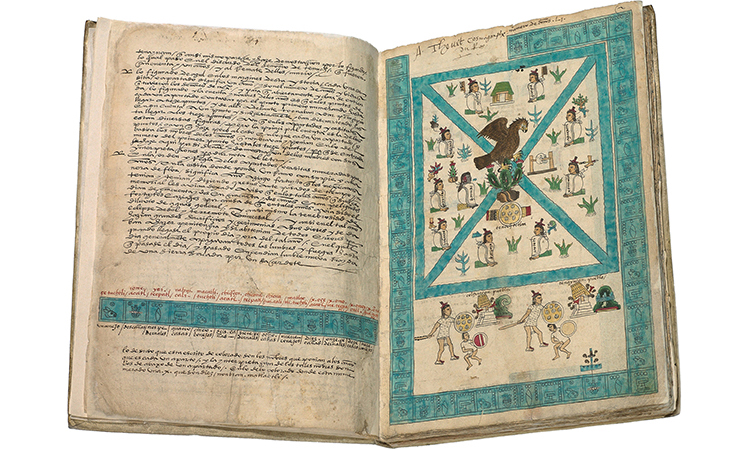

Frontispiece, Codex Mendoza, Viceroyalty of New Spain, c. 1541–42, pigment on paper © Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford

We can regain some aspects of a Mexica perspective on the history and organization of Tenochtitlan from the frontispiece of the Codex Mendoza, a manuscript commissioned in 1541 by the first New Spanish Viceroy, Antonio de Mendoza. The Mexica artist divides the city into four quarters, reflecting Indigenous ideas about the ordering of the universe. Because much of Tenochtitlan is now buried beneath modern day Mexico City, the frontispiece aids in understanding conceptualizations of the space of the city. Much of the information in the map relates not only to space, but also to history—the succession of Mexica rulers appears in each quadrant. While commissioned by and for Spaniards, the Codex Mendoza (like other early colonial manuscripts) was created by Indigenous artists whose voices and perspectives are centered.

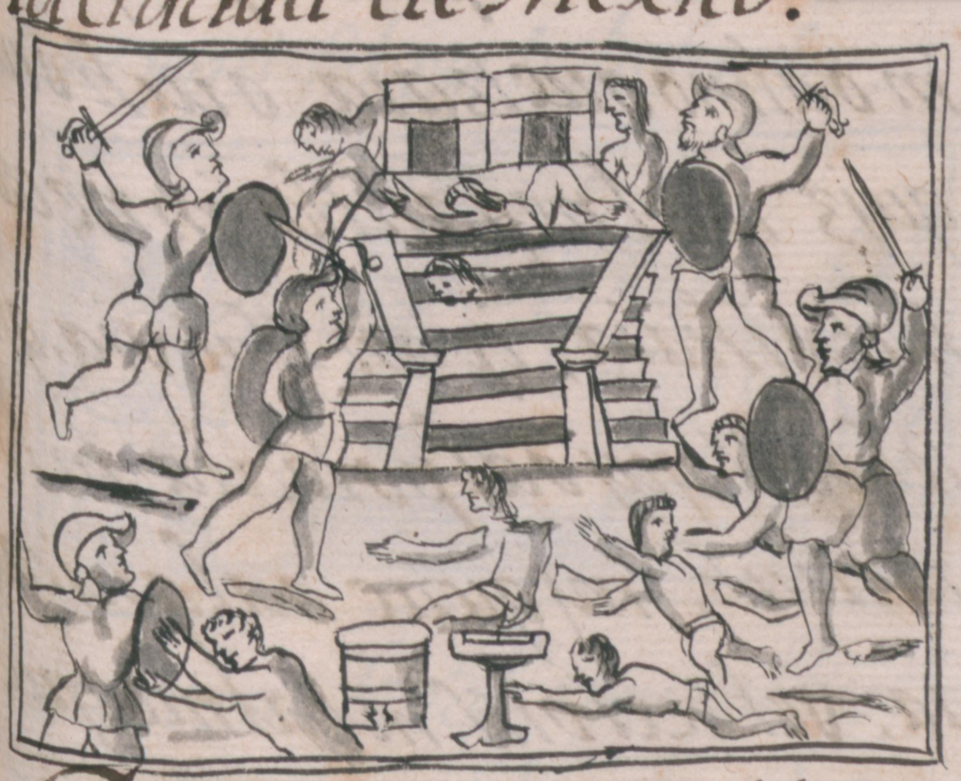

“Toxcatl Massacre,” Bernardino de Sahagún and collaborators, General History of the Things of New Spain, also called the Florentine Codex, vol. 3, book. 12, 1575–1577, watercolor, paper, contemporary vellum Spanish binding, open 32 x 43 cm, closed 32 x 22 x 5 cm (Medicea Laurenziana Library, Florence, Italy)

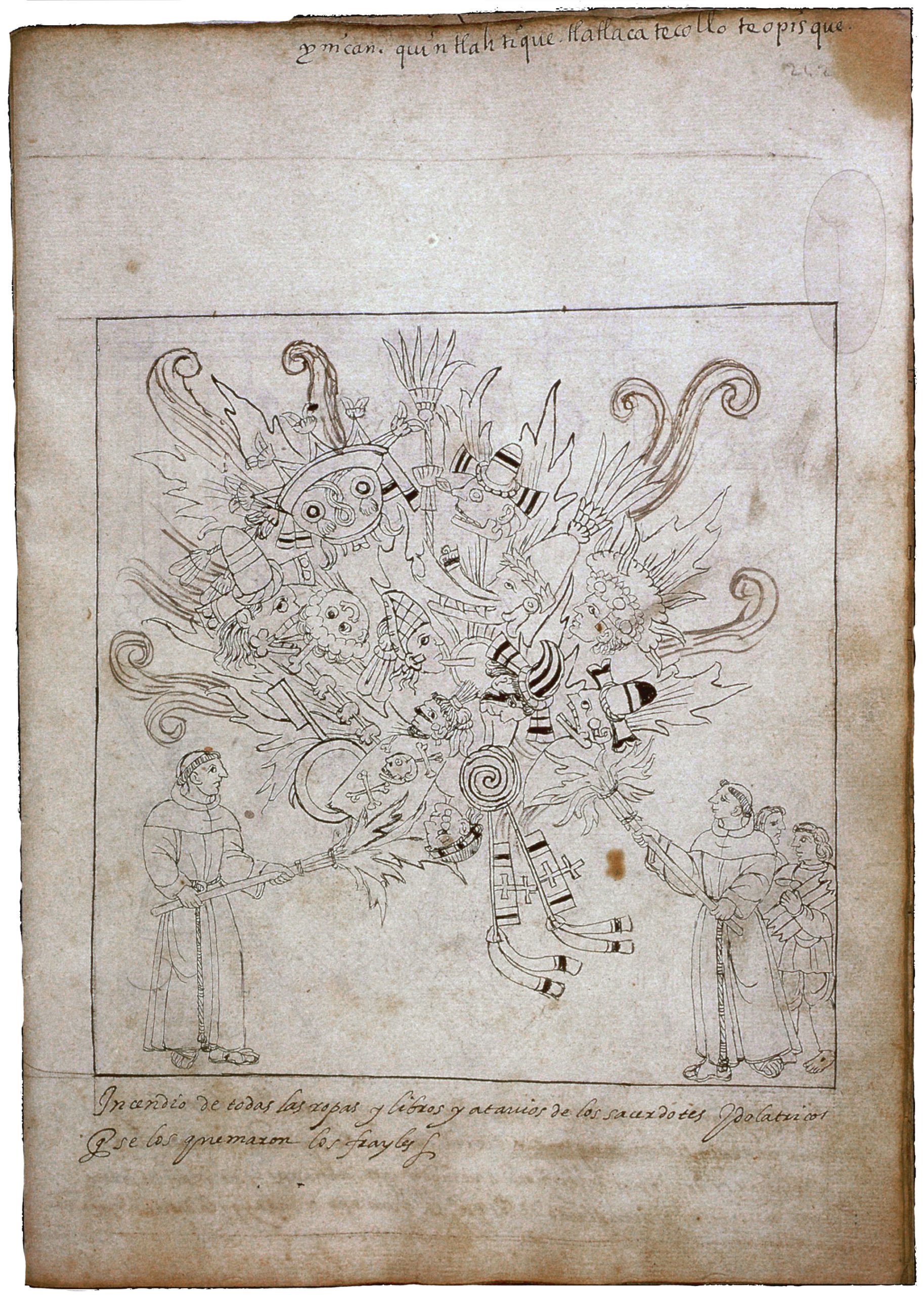

Tlacuiloque (scribes) also recorded events of the military conquest. While Moctezuma and Cortés had first encountered each other at the entrance to the city in November of 1519, violence did not break out until May of 1520. The conquistadors launched their attack during the Mexica celebration of Toxcatl, an important festival dedicated to the god Tezcatlipoca, “lord of the smoking mirror.” The violent attack is recorded in the Florentine Codex. One column contains text written by the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagún and those of his Indigenous collaborators in another, the latter of whom spare no details in describing and illustrating the cruelty of the Spaniards attacking the unarmed Mexica men.

The violence of the conquest is illustrated again over a hundred years later, this time from an entirely Spanish perspective, in a biombo that represents both the conquest and a view of Mexico City. Used as a folding screen to divide a domestic space in an upper-class criollo home, the biombo is modeled after its Japanese predecessor the byōbu. New Spain and Asia were connected through the Manila Galleon trade, a further expression of the globalized world that will be further explored in the later section on visual splendor.

The biombo depicts the conquest on one side and an idealized birds’ eye view of the city of Tenochtitlan on another. The conquest side teems with the chaos of the military conquest. The opposite side, by contrast, is devoid of human life, projecting an idealized vision of Mexico-Tenochtitlan.

Read essays about the visual culture of conquest

Images of Africans in the Codex Telleriano Remensis and Codex Azcatitlan: Indigenous artists in Mexico produced the first images of Black Africans in the Americas.

Read Now >

Frontispiece of the Codex Mendoza: This Codex contains a wealth of information about the Mexica and their empire.

Read Now >

Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City: This screen offers an idealized bird’s eye view of Mexico City on one side, and depicts the Conquest on the other.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Art, Architecture, and Evangelization

Convento San Agustín de Acolman, c. 1539–80, Mexico (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The military conquest in Mexico was complete by 1521. Thereafter the conquest shifted from one focused on military subjugation to one focused on religious conversion. In the mid-sixteenth century members of the mendicant orders arrived en masse, including Franciscans, Augustinians, Dominicans, and Jesuits to convert Indigenous people to Christianity. It was a period of religious fervor in Europe, with Spain jockeying to assert itself as exemplative of Catholic orthodoxy in Western Europe.

Map of the Iberian Peninsula in 1492

Spain, in fact, had a long history dating back to the Middle Ages of religious heterogeneity. A series of Muslim caliphates controlled the Iberian peninsula (Spain and Portugal) beginning with the Umayyad dynasty in the eighth century. Gradually over the centuries, various Muslim groups came to control much of the peninsula that they called al-Andalus. Over a period of some 700 years, Catholic Spaniards waged military campaigns to (re)capture Iberia from Muslims. By the late fifteenth century, the last Muslim settlement in Spain was in the southern city of Granada. This context is relevant to the Americas because in 1492 Columbus famously “sailed the sea so blue” on behalf of the Spanish crown and in the same year Spain officially expelled its Jewish inhabitants. Shortly before this, in 1478, the King and Queen of Castile and Aragon, Ferdinand and Isabel, established the Holy Order of the Inquisition, a tribunal established to cement Spain as united under their Catholic crown.

Ex-Convento de San Miguel, Huejotzingo, constructed 1526–70 (photo: Airvillanueva, CC BY-SA 3.0)

These utopian goals of creating a global Christendom played out in the missionary process in the Americas. Many Indigenous peoples encountered Spanish culture first through the church. Mission complexes, called conventos, were built by Indigenous laborers throughout the territories. Conversion processes occurred within and around these spaces, causing modern scholars to describe them as “theaters of conversion.” Often enclosed by heavy fortress-like walls, conventos contained cells for the resident monks, a refectory, kitchen, offices, meeting rooms, chapels, an infirmary, and storage rooms.

![Diego Valadés, “The Ideal Atrium,” 1579, copperplate engraving, within Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi et orandi usum accommodate […] ex Indorum maximè deprompta sunt historiis. Perugia: Petrus Jacobus Petrutius, 1579.](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/RC-atrium.jpg)

This image of an ideal atrium shows Franciscan friars engaging in a different activities related to the evangelization of the Indigenous populations in New Spain. Diego Valadés, “The Ideal Atrium,” complete with four posa chapels in the corners, 1579, copperplate engraving, within Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi et orandi usum accommodate […] ex Indorum maximè deprompta sunt historiis. Perugia: Petrus Jacobus Petrutius, 1579 (Getty Research Institute)

The walled complex of the conventos also included outdoor spaces such as a capilla india used for preaching to the Indigenous population, and smaller posa chapels arranged around a rectangular atrium, used for processions and ritual activities. The convento’s functions are described In a text written and illustrated by the mestizo Franciscan friar Diego Valadés in Rhetorica Christiana. Valadés describes the convento’s functions, and in one engraving shows how the various spaces were used by Spanish friars as well as Indigenous converts.

Atrial Cross, San Agustín de Acolman (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Because Indigenous artists and architects built these mission complexes, much of their construction and related objects incorporate elements of both Indigenous and European visual culture. A common example of this hybridity is seen in large sculpted crosses housed in the outdoor atrium of many conventos that mendicant friars used as teaching tools to evangelize the local Indigenous population.

Atrial Cross, San Agustín de Acolman (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Indigenous artists, under the patronage of the local mendicant order, translated scenes from Christ’s Passion story into glyph-like forms on the crosses, utilizing ways of seeing that were familiar to the Indigenous population. Furthermore, their outdoor location allowed for larger gatherings, and may have encouraged the Indigenous population to convert due to their familiarity with outdoor worship and rituals conducted in the outdoor setting of Mesoamerican sacred precincts.

The conversion of the Indigenous populations of the Americas was fraught with power imbalances and cultural imperialism. As Spanish missionaries imparted the Christian faith to local populations, they aimed to supersede local religious practices. While the evangelization in the region was largely successful, the art and architecture (particularly of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries), shows the ways that Indigenous artists put their own mark on their Christian commissions, thereby creating an Indigenized form of Christian visual and material culture.

Watch videos and read essays about art, architecture, and evangelization

Mission churches as theaters of conversion in New Spain: Built by Catholic monks to convert the Indigenous population, these spaces combined Mesoamerican and European forms.

Read Now >

![Diego Valadés, “The Ideal Atrium,” 1579, copperplate engraving, within Rhetorica Christiana ad concionandi et orandi usum accommodate […] ex Indorum maximè deprompta sunt historiis. Perugia: Petrus Jacobus Petrutius, 1579.](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/RC-atrium-copy-2.jpg)

Engravings in Diego de Valadés’s Rhetorica Christiana: The first book ever printed by an American author.

Read Now >

Atrial Cross at Acolman: The convento atrium was a place for preaching. This cross taught new converts about Christianity.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Art and Identity

As the Spanish colonial world matured, those in power developed anxieties about maintaining control. As early as 1537 New Spanish Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza wrote to the Spanish king Charles I about the fear of an African and Indigenous collusion. Efforts were continually made to segregate Indigenous and African populations from each other as a means of control. While the three main races of the Spanish colonial world were in reality closely connected via marriage and the resultant mixed race offspring, Spanish and criollo elites wished to maintain a lineage they called limpieza de sangre, literally cleanliness of blood. By declaring oneself fully Spanish and an “Old Christian,” criollos aimed to elevate their status in comparison to the peninsulares. As these constructions of identity developed, so too did modes of categorizing and representing those who fell outside of constructed categories of whiteness.

Casta Painting, 18th century, oil on canvas, 148 x 104 cm (Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Mexico)

Perhaps some of the most visual fascinating examples of constructions of identity are casta paintings produced in eighteenth-century Mexico. Made typically in sets of sixteen (or one panel with sixteen vignettes), the series usually begins with a Spanish husband and Indigenous (“India”) wife along with their mestizo children. The second panel then typically includes a Spanish husband with an African (“negro”) wife and their mulato children. As the sixteen paintings develop, the racial mixtures become more complex with combinations of Spanish, African, and Indigenous spouses and children.

Spaniard and Indian Produce a Mestizo, attributed to Juan Rodríguez Juárez, c. 1715, oil on canvas (Breamore House, Hampshire, UK)

Earlier examples of casta paintings, such as a set by Juan Rodríguez Juarez, are relatively idealized, showing the bounty of the land and the richness of its inhabitants. Later in the eighteenth century distinctions emerge featuring negative behavior and lower socioeconomic status, particularly within paintings that include individuals with African ancestry.

Detail of panel 2–5, Francisco Clapera, set of sixteen casta paintings, c. 1775, 51.1 x 39.6 cm (Denver Art Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In some examples, an African wife is seen beating her Spanish husband, indicating especially negative stereotypes around intermarriage between Blacks and Spaniards. When Spaniards intermarried with Indigenous people, they were seen to “achieve” whiteness after several generations. In contrast, even after several generations, a mixed-race Black mother and Spanish father could produce a “torna atras,” literally “returns backwards,” indicating the stigma attached to Blackness and Black people. Casta paintings attempted to classify the natural world, but they are far from scientific. They aim to construct categories of racial mixture as if they were stable, when in reality these identities were never immutable. People could in fact use phenotype, class, education, and proximity to power and influence to re-invent themselves in different contexts, thereby proving that these categories were far from fixed.

Juan Rodríguez Juárez, Portrait of the Viceroy, the Duke of Linares, c. 1717, oil on canvas, 81.88 x 50.39 inches (MUNAL)

Casta paintings are only one category of secular art that dealt with issues of race and representation. Another important genre tied to issues of identity is colonial portraiture. Unlike casta paintings which depict generic racialized types, portraits typically feature a specific individual’s likeness, and were usually inscribed with identifying information in a panel within the image called a cartouche. In addition to recording the person’s appearance, the portraits tended to focus on symbols of their wealth and status as expressed in their clothing, jewelry, and personal adornment.

Painted after her death by famed Mexican artist Miguel Cabrera, this portrait focuses less on the likeness of the famous literary nun Sor Juana and more on showcasing the wealth and learning of the elite New Spanish convent. Miguel Cabrera, Portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, c. 1750, oil on canvas (Museo Nacional de Historia, Castillo de Chapultepec, Mexico; photo: Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

One example of this portrait tradition visualizes the criolla nun Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. Typically the focus in female portraits was on the dress, whether the fine jewelry and silks of secular women, or the habits and escudos of nuns. Here, Sor Juana, sometimes known as the Americas’ first feminist, is shown in the tradition of male scholar portraits, in her library surrounded by books and instruments of learning. With her right hand she thumbs the pages of a large book on the desk in front of her and with the left hand she grasps a rosary, thereby showing the importance of the church in a life of learning.

Watch videos and read essays about art and identity

Francisco Clapera, set of sixteen casta paintings: Casta paintings used labels and visual details such as different skin tones, dress, occupations, and settings to distinguish ethnicity and to signal economic and class divisions

Read Now >

Spaniard and Indian Produce a Mestizo, attributed to Juan Rodríguez Juárez: Casta paintings come from a place of social and racial anxiety.

Read Now >

Elite secular art in New Spain: Elites decorated their private residencies with portraits, furniture, silver, textiles, and ceramics to showcase their wealth and status in colonial society.

Read Now >

Miguel Cabrera, Portrait of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Miguel Cabrera’s posthumous portrait is a famous depiction of the esteemed Mexican nun and writer.

Read Now >/4 Completed

Visual Splendor

José Manuel de la Cerda, Writing cabinet on table, c. 1750, Wood, Mexican lacquer, gilding, and silver drawer pulls, 102 x 155 cm (The Hispanic Society)

Colonial elites also showcased their status through the objects they collected and displayed in their luxurious homes, churches, and civic spaces. Beyond painting, the splendorous objects of the colonial world incorporated precious metals, brilliantly colored feathers, lacquered shell-inlaid woods, embroidered textiles, and delicately carved ivories (among many other materials and techniques). These traditions drew not only from European prototypes, but also showcase a melding of visual and material culture from the Americas, Africa, Europe, and Asia.

Hearst Chalice, currently unidentified artists, made in Mexico City, 1575–78, silver gilt, rock crystal, wood, and feathers, 33 cm high, 22.9 cm in diameter (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

While undoubtedly products of a great cultural burgeoning, these sumptuous objects are also the result of violent and oppressive extraction of wealth and labor. The Spanish Crown taxed precious metals based on the “royal fifth,” thereby playing a major role in fostering the silver mining system, based in Mexico at Zacatecas. While lucrative for a select few, mining was extremely dangerous for the Black and Indigenous laborers, the majority of whom were enslaved. Examining an object like the Hearst Chalice showcases the great wealth of the crown and the skill of the silversmiths, but it is also an important reminder of Black and Indigenous labor and creativity in metalworking and featherworking.

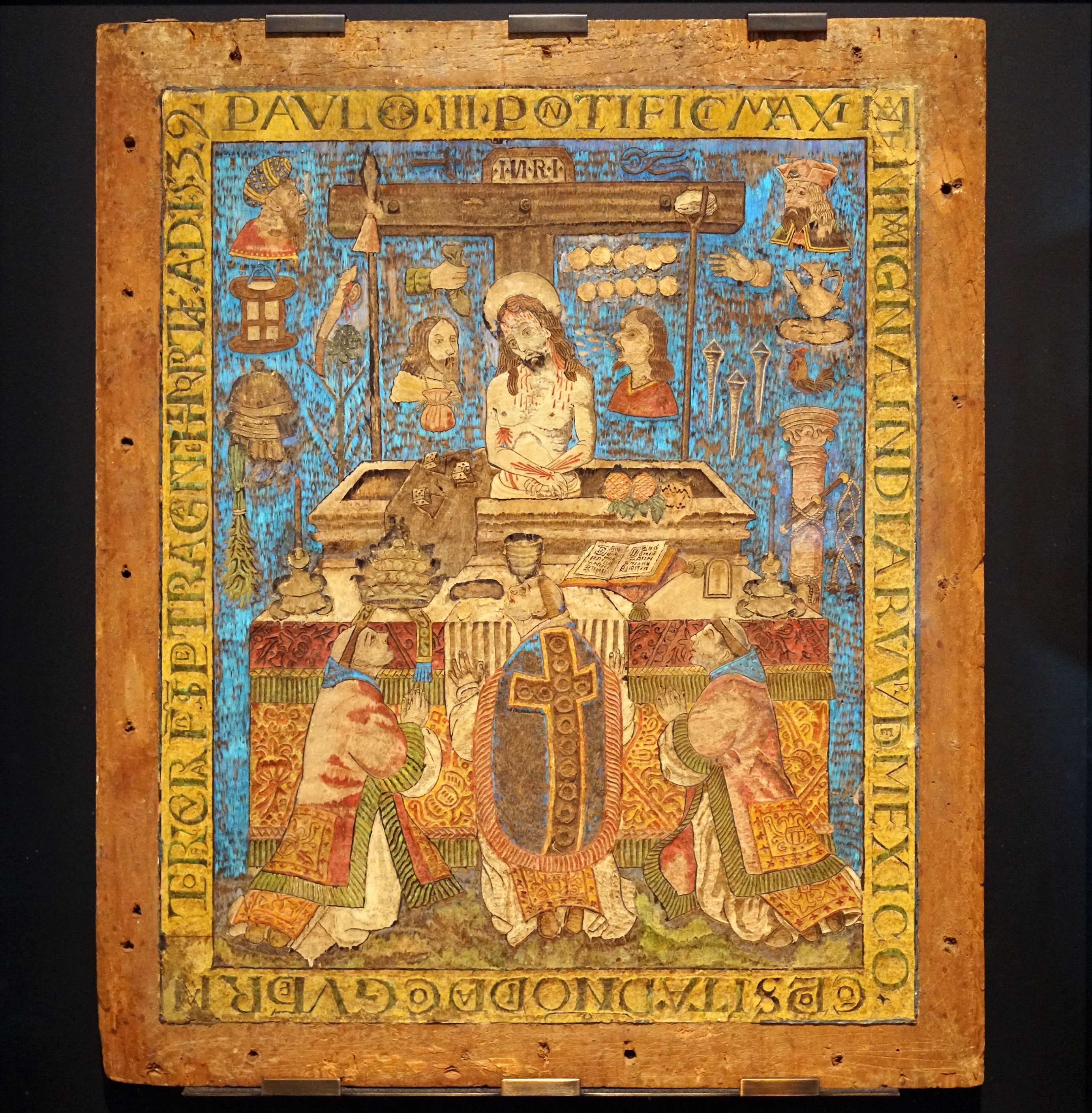

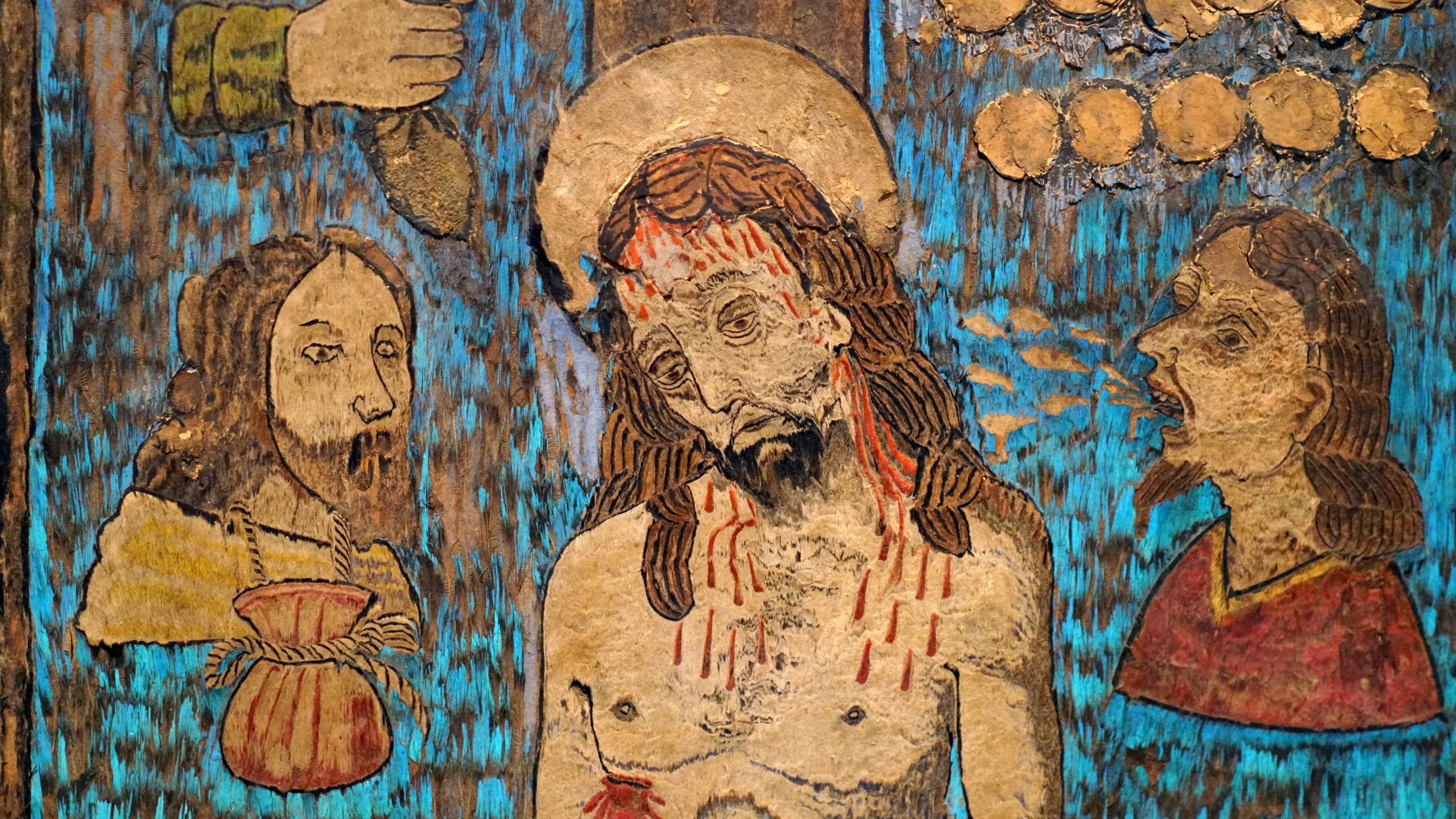

The Mass of St. Gregory, 1539, feathers on wood with touches of paint, 26 1/4 x 22 inches / 68 x 56 cm (Musee des Jacobins; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Featherwork, an artistic medium developed much earlier in Mesoamerica, employs brilliantly colored feathers glued to a matrix to create iridescent objects of various kinds. As noted earlier, beginning in the early colonial period, church patrons sought to combine the elite arts of Indigenous Mesoamerica with imported European visual culture. Originally used by the Mexica for various types of regalia including miters, shields, and headdresses, featherworkers in the colonial period combined it with the two-dimensional tradition of panel painting, adapting imported European prints to create stunning examples of featherwork mosaics depicting Christian subjects.

Map showing the routes of the Manila Galleon trade

It was not only the combining of Indigenous and European styles, subjects, and techniques that distinguished the visual arts in New Spain. Asian imported goods were wildly popular throughout the Spanish world, and soon local artists created their own versions such as those seen in biombos. Chinese, Japanese, and Indian goods were exported via the Manila Galleon that left the Spanish-controlled Philippines once a year, headed for Acapulco.

Christ Crucified, 17th century, ivory (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Seventeenth-century artists, possibly artists from China working in Manila, carved ivories with Christian subjects specifically for export to New Spain. Using traditional techniques and materials, namely ivory, these artists created highly sought after liturgical objects. Of the Chinese sculptors, the first bishop of Manila wrote:

with their ability to replicate those images that come from Spain, I understand that it should not be long when even those made in Flanders will not be missed.Domingo de Salazar, 1st bishop of Manila in 1590

The ivories are remarkable in showing the global reach of the Spanish empire, spanning three continents and showcasing worldly and elite tastes.

Miguel González, The Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe), c. 1698, oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl (enconchado), canvas: 99.06 × 69.85 cm / frame: 124.46 × 95.25 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

The seventeenth-century vogue for Asian and Asian-inspired goods was also seen in enconchados, objects made of wood inlaid with mother-of-pearl. They varied in form from panel painting and decorative boxes to biombo screens. Subjects could be either sacred or secular. Enconchados were inspired not only by Japanese lacquer work, but also may have derived from Mesoamerican shell working traditions. Asian and Asian-inspired objects like enconchados, ivories, and biombos were prized for their craftsmanship as well as their ties to Asia, thereby projecting the wealth and expansive global knowledge of their owners.

Watch videos and read essays about visual splendor

The Mass of St. Gregory: In 1539, the Nahua noble and governor of Mexico City commissioned this featherwork for Pope Paul III.

Read Now >

Screen with the Siege of Belgrade and Hunting Scene (or Brooklyn Biombo): Japanese objects came through Mexico on their way to Spain, and had a lasting impact on the arts of the New World.

Read Now >

Miguel González, The Virgin of Guadalupe: Some of the most remarkable images of the Virgin of Guadalupe are created not entirely in paint, but also include mother-of-pearl, or enconchado.

Read Now >

/4 Completed

The Global Baroque

Jerónimo de Balbás, Altar of the Kings (Altar de los Reyes), 1718-37, Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary (Mexico City) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Eighteenth-century Mexico saw these global trends crescendo into a style known as the ultrabaroque, a local iteration of the ornate and expressive dynamic baroque art of Europe. The great wealth of the colony was showcased in massive churches with ornate gilded altarpieces such as the Altar of the Kings in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico City.

Church of Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: Luidger, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In Taxco, a town whose wealth derived from the local silver mine, the church of Sts. Prisca and Sebastian is massive and ornately decorated following the latest trends in the elaborate baroque style preferred in the Spanish world, especially in New Spain.

Watch a video and read an essay about the global baroque

Jerónimo de Balbás, Altar of the Kings (Altar de los Reyes): A sumptuous feast for the eyes in the Metropolitan Cathedral in Mexico City.

Read Now >

Church of Santa Prisca and San Sebastian, Taxco, Mexico: An ornate church that reflects the incredible wealth of local silver mining operations.

Read Now >/2 Completed

The reality is that great displays of wealth oftentimes resulted from abuses of power and this is also true in New Spain. These ethical issues linger in today’s world. The Spanish colonial world is not that far removed from our own. Objects continue to reflect more than their brilliant surfaces, but also the lands and hands of their genesis.

Notes:

[1] Ilona Katzew and Rachel Kaplan, “Hearst Chalice,” in Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800, ed. Ilona Katzew (New York: DelMonico Books, 2022), pp. 101–06.

Key questions to guide your reading

How were the visual arts in New Spain emblematic of an expanding globalized world?

What is the relationship between materials or techniques and cross-cultural exchange?

Jump down to Terms to KnowHow were the visual arts in New Spain emblematic of an expanding globalized world?

What is the relationship between materials or techniques and cross-cultural exchange?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Atrium

Atrial cross

Capilla india

Casta painting

Codex

Convento

Criollo

Featherwork

Manila Galleon trade

Mendicant orders

Peninsulare

Posa chapel

Tlacuiloque

Ultrabaroque

Viceroy

Viceroyalty

Learn more

Vistas: visual culture in Latin America, 1520–1820

Archive of the World: Art and Imagination in Spanish America, 1500–1800, ed. Ilona Katzew (New York: DelMonico Books, 2022).

Ilona Katzew and Rachel Kaplan, “‘Like the Flame of Fire’: A New Look at the ‘Hearst’ Chalice,” Latin American and Latinx Visual Culture 3, no. 1 (2021): pp. 4–29.

James Oles, Art and Architecture in Mexico (London: Thames & Hudson, 2013).

Painting a New World, exh. cat., ed. Donna Pierce, Denver Art Museum (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004) (available online).

Tesoros, Treasures, Tesouros, the Arts in Latin America, 1492–1820, exhibition catalogue (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2006).

Kelly Donahue-Wallace, Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521–1821 (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008).