Japanese objects came through Mexico on their way to Spain, and had a lasting impact on the arts of the Americas.

Screen with the Siege of Belgrade and Hunting Scene (or Brooklyn Biombo), Circle of the González family, c. 1697–1701, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum and Museo Nacional del Virreinato – INAH, Tepotzotlán). Speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Lauren G. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:05] We’re standing here in front of a folding screen from Mexico, made about 1700.

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:11] This is wild. This is one of the most complicated objects I have ever looked at.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:17] It’s a really unique object. This folding screen is inspired by Japanese folding screens. We call it a biombo. A biombo comes from the Japanese word for folding screen.

Dr. Zucker: [0:27] This is a word that would have been used in the Spanish colony that is now Mexico.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:32] Right. At this point in time, Mexico is part of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, comprised of parts of the southwestern United States, Mexico, and down through Central America. The viceroy is the administrator for the king.

Dr. Zucker: [0:44] You have the king in Spain, his colony in the New World, and they’re looking to Japan for inspiration.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:51] Exactly. Early in the 17th century, there’s this interest in Japanese objects that are coming to Mexico from the Philippines, which is also controlled by Spain at this time.

Dr. Zucker: [1:01] Why was there trade with the Philippines? What was being traded?

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:04] The types of objects being traded included folding screens, lacquerware boxes, ivory goods, and other luxury items.

Dr. Zucker: [1:11] I’m seeing, at the base and at the top, black that looks very much like Japanese lacquer.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:16] As these lacquer boxes are coming into Mexico, there’s this craze for Japanese goods or Japanese-inspired goods. What we see here is a Mexican artist who has created something in the guise of a Japanese lacquerware box. The bottom elements have these beautiful Japanese landscape elements. Then you get the decorative floral elements bordering the entirety of the screen.

Dr. Zucker: [1:38] This must have been fabulously expensive and the height of what was in vogue at this moment.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:43] Absolutely. In fact, we know who owned this object. It was the viceroy himself, José Sarmiento de Valladares.

Dr. Zucker: [1:49] We know that, at that moment, there’s tremendous money being generated by these colonies.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [1:54] At this time, you have a huge silver mining industry, raw goods like cochineal, tobacco, various other types of things that are all being sent back to Europe. People like the viceroy are able to acquire these types of goods and put them on display in their homes.

Dr. Zucker: [2:08] Let’s take a look at the screen itself. Most striking, at least from this side, is this battle scene.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:13] Half the battle scene. This biombo is only half of the original. The other half is in a museum in Mexico City. We’re presented with this really chaotic scene between members of the Hapsburg Empire, the Spanish empire at the time, and the Turks.

Dr. Zucker: [2:28] The Hapsburgs — the family that ruled Spain and was in control of so much of the New World but was also in control of Central Europe.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:36] The scene that it’s showing is taking place not long before this object is produced. This battle is very contemporary.

Dr. Zucker: [2:45] We’re seeing the Battle of Belgrade between the Ottoman Turks encroaching into Central Europe, but here we are in Mexico, and this is a Japanese screen. It’s mind-blowing.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [2:55] Mexico being in the middle of all these networks of exchange, the transpacific exchange, objects being traded from Asia going through Mexico back to Europe, objects being traded from Europe that are then going through Mexico to Asia.

Dr. Zucker: [3:06] It blows apart the way in which we’re usually taught history.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:10] Stylistic categories can often break down when you see things that speak to so many different cultures.

Dr. Zucker: [3:16] Let’s look really closely at the styles in this screen. What I’m seeing is not only this delicate, very thin painting, which is almost like drawing, but I’m also seeing these areas that are brilliantly illuminated and it’s shell.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:30] This object is truly unique because this is not only a biombo, but this is part of the only known surviving biombo enconchado. Enconchado means shell inlay. This is a shell-encrusted biombo. It’s a combination of oil painting and mother-of-pearl that’s been placed into the screen itself.

Dr. Zucker: [3:49] I can see it in the helmet, which is making the helmet seem to shine. It’s probably most prominent in floral motifs that are at the very top that frame the battle scene.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [3:58] You have to imagine, when this is placed in a room, how different parts of it would grab your attention because of the flickering candlelight. We don’t know exactly who the artist of this biombo was.

[4:07] What we do know is that it’s being made locally. It’s made by an artist in New Spain at the time for the viceroy, most likely to be placed inside of his new palace in Mexico City.

Dr. Zucker: [4:17] Who would have seen this? Who was the intended audience?

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:20] Each side of the biombo was intended for different audiences. The side with the battle would’ve been intended for the viceroy, people coming to visit the viceroy, important individuals, people who he’s bringing into his reception room, essentially.

Dr. Zucker: [4:33] This would have a political use as an expression of his power.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:36] This particular viceroy has come from Spain to rule over this colony. This would assert the dominance of the Hapsburgs in Mexico.

Dr. Zucker: [4:44] [And] globally, since this is also the Hapsburgs’ victory over the Ottomans. I want to go see the other side. This is completely different. This feels so much more relaxed. It feels much more decorative. The way that the decorative border hangs, it looks like it’s textile.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [4:59] It’s a hunting scene. It really is showcasing the artist’s ability to display for us this beautiful landscape scene. I agree with you that the side looks like this beautiful Asian-inspired tapestry that might be hanging in someone’s room, someone of this wealthy status.

Dr. Zucker: [5:14] We know that the design, at least for the hunting scene, came from a Medici tapestry that was made in France.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [5:19] The tapestry was then copied into a print. That’s how it appears here in Mexico. The same thing with the other side with the battle scene, it was also based off of a print coming from Europe.

Dr. Zucker: [5:29] I love this side of the screen. You have, again, a footing, which is reminiscent of lacquerware from Japan, but then above that is this very dense botanical motif with all these blossoms, creating this frame that allows us to look into this deep space, into this spectacular landscape.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [5:46] The hunting scene that we have, a feast for the eye in terms of landscape elements and beautiful brushwork on display here.

Dr. Zucker: [5:53] It’s almost hard to remember that we’re in the New World when we’re looking at this side of the screen. The motifs seem so European.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [6:01] On both sides of the screen, there’s a lot of classicizing elements. The swags at the top, held in the mouth by lions, this is a very classical element that you see in the Renaissance that’s coming from ancient Rome. This side of the screen was intended for a very different audience than the battle scene.

[6:17] The battle scene was intended for the individuals the viceroy would be receiving. This actual side of the folding screen would have been largely viewed by women. Imagine this is essentially the room where the viceroy’s wife and perhaps friends, etc. would gather to have hot chocolate, to smoke, which is very common at this time, and to engage in conversation.

[6:39] An interesting biographical fact about the viceroy that speaks to this interesting historical moment, is that his first wife was a descendant from the line of Moctezuma II, who was the Aztec ruler who died during the Battle of Tenochtitlan during the Spanish conquest.

Dr. Zucker: [6:55] What’s fascinating then is that that older royal lineage, even though they were conquered, remains important.

Dr. Kilroy-Ewbank: [7:01] You see that throughout the Spanish Americas, where Indigenous peoples who can trace their lineage back to rulers are given certain benefits that other Indigenous peoples are not. It’s complicated and it’s hard to know where to situate the objects, but that’s also what makes it so exciting and engaging.

[7:18] [music]

Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), here, showing the front, c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A chaotic battle scene unfolds across six panels of a folding screen. The seemingly endless amount of human bodies, animals, weapons, and buildings are difficult to differentiate without careful, slow looking. On land and sea, the battle scene pits countless warriors against one another in violent conflict. Fallen soldiers spill over the side of a boat into the water, with body parts floating around the vessel.

“Barcas cogidas en el Danubio” (“boats caught on the Danube River”) appears underneath the ship while canons fire in the foreground. Upper right corner, Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), detail of the front, c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Canons shoot, lances impale, swords are raised, heads appear on pikes—all these details emphasize the horrors of war. Short, descriptive Spanish inscriptions on the screen, such as “Barcas cogidas en el Danubio” (boats caught on the Danube River), guide viewers.

Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), here the reverse, c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

This battle scene forms one side of a double-sided folding screen made around 1700 in the viceroyalty of New Spain; the other side shows no sense of violent conflict between warring forces, but rather is a hunt set in a bucolic forest.

A feline attacks a fallen hunter, and is itself about to be speared by three men on horseback. Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), detail of the reverse, c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The hunting scene is not free of violence though; a spotted feline attacks a fallen hunter, and is itself about to be speared by three men on horseback. Another big cat pounces on a surprised hunter on horseback. Dogs aid hunters in tracking animals. Still, the scene is largely focused on large trees, rolling hills, and delicately painted plants and flowers.

Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), detail of the reverse, c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Vines, garlands, and more flowers adorn the screen’s edges on both sides. Further animating both scenes is the varied color palette, fanciful brushwork, and use of inlaid shell (here, mother-of-pearl). Our eyes can’t help but be attracted to the shell’s luster, almost playfully leading our eye across the screen. And this isn’t even the entire folding screen!

Folding Screen with a Scene from the Siege of Vienna (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse, not pictured), here showing the front, c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Museo Nacional del Virreinato, Tepotzotlán)

These six double-side panels are but half of an original screen that was composed of 12 panels—the half this essay focuses on is in the Brooklyn Museum today; the other half is in the Museum of Viceregal Art in Tepotzotlán near Mexico City. [1] This folding screen perfectly encapsulates the cosmoplitanism of colonial Mexico and its art, and the may ways that local artists borrowed from and adapted materials, forms, and subjects from near and far to create something new. It also provides a window onto several important themes: transpacific and transatlantic trade, elite and nonreligious objects, and visual transculturalism.

Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), detail of the reverse, c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Made for a palace

Created for viceroy José Sarmiento de Valladares, the count of Moctezuma, the folding screen was likely made for his palace—which still rests on the main plaza or zócalo of Mexico City. [2] Less than a decade before his 5-year reign, the viceregal palace had been burned and partly destroyed after uprisings over food shortages in 1692. After Sarmiento de Valladares became the viceroy, he began to rebuild the palace, and needed new furnishings for the space. This lavish folding screen, with the added opulence of mother-of-pearl inlay, was likely made to help in this process of refurbishment, along with many other luxurious items. What a statement it would have made to guests who viewed it!

Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Folding screens (called biombos) acted as room dividers, and they were often found in state rooms and reception rooms. In the viceregal palace, a screen such as the Brooklyn Biombo most likely separated the piano nobile (formal reception hall) from the estrado (women’s sitting room). Local and international visitors who came to converse with the viceroy would have been struck by the shimmering surface of the biombo’s battle scene, while guests in the women’s sitting room would have had a fitting conversation starter with the hunting scene while they talked, drank chocolate, sewed, and smoked.

Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), detail of the front, c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Transpacific and transatlantic trade and exchanges

Contemporary battles

Miguel González, The Conquest of Mexico, Tabla XX (detail), late 17th century, organic pigments, ink, stucco, nacre, and organic varnish on scrim panel, 52 x 100 cm (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires)

As the viceroy rebuilt the palace, he filled the space with paintings of the Spanish conquest and other types of battle scenes or themes related to power—such as a series of paintings with shell inlay made by Miguel González (today in the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires).

The battle scene on this biombo was not focused on the conquest of Mexico, which by this point had occurred more than 150 years earlier. Rather, it depicts a battle of in what is now called the Great Turkish War (1683–99). The war pitted Habsburg forces against Ottoman ones.

Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), detail of the front, c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Brooklyn Biombo shows the Siege of Belgrade, one battle of the War that occurred on 6 September 1688. The Tepotzotlán screen shows another battle, the Siege of Vienna, which occurred on 12 September 1683, and which resulted in the Holy League defeating Ottoman troops. When the War finally ended in 1699, Habsburg power was solidified in central and southeastern Europe.

Romeyn de Hooghe, Belgrade Taken by Storm by Maximilian Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria, September 6, 1688, 1688, engraving, 47 x 58 cm (Rijksmuseum)

Prints made originally in Holland served as models for the battle scenes. They were made less than thirteen years before Sarmiento de Valladares’s arrival in New Spain by the Dutch printmaker Romeyn de Hooghe. His etchings were popular in Holland among people following the war with interest, and his images were popular in New Spain as well. De Hooghe was well-known for his prints of military exploits, and they offered a way for peoples in New Spain—separated from the war by an ocean—to visualize what happened in it.

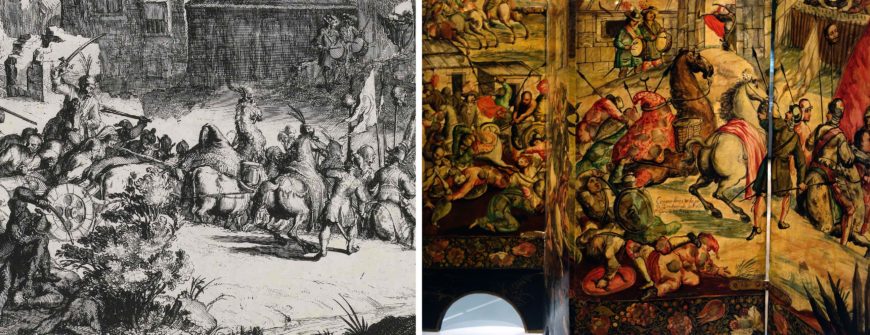

Left: Detail of Romeyn de Hooghe, Belgrade Taken by Storm by Maximilian Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria, September 6, 1688, 1688, engraving, 47 x 58 cm (Rijksmuseum); right: detail of battle scene in Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The battle scenes that play out on both the Brooklyn and Tepotzotlán panels showcase not only the violence of the war, but also cast it as one of formidable opposites. The Ottoman forces are not shown as weak nor incapable, but strong and capable warriors; showing them in this way only elevated the strength of Habsburg forces who eventually would win. The choice of these two battle scenes advertised Habsburg power—a power that extended to Sarmiento de Valladares as the Spanish Habsburg king’s representative (as viceroy) in New Spain. The battle scenes also demonstrate Sarmiento de Valladares’s allegiance to the Habsburg Crown. His coat of arms is located in the upper-left corner (on the Tepotzotlán half), no doubt to associate himself with the Habsburg rulers and their victories. His support of the Habsburgs was clearly on display for any visitor to his reception room.

Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City, view of scenes of the Conquest, New Spain, late 17th century (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While the battle scene does not show events of the Spanish Conquest of Tenochtitlan (that occurred 1519–21), it does visually parallel the many other artworks of the time that did. In another biombo (not made for Sarmiento de Valladares) that shows the Conquest, the artist paints so many battling figures that the scene is similarly chaotic. Like the Siege of Belgrade on the Brooklyn Biombo, the fighting also occurs on the water, and there is a mountainous landscape behind the scene in the top portion of the biombo. Despite the different historical moments that each artist tried to capture, they clearly drew on similar visual conventions to convey conflict between Spanish forces and their enemies. Visitors likely would have made associations with the different conflicts set on land and water.

Hunting scenes

As the use of de Hooghe’s prints indicates, local New Spanish artists adapted and transformed European prints—as was also common among artists in Europe and elsewhere that prints were sent. The hunting scene on the biombo further demonstrates the far-flung networks that connected people in the seventeenth century—across land and sea. It was not just the battle scenes painted in New Spain that were adapted from European prints. The hunting scene likewise borrowed from prints that replicated tapestries and drawings by Johannes Stradanus (Jan van der Straet) and Gobelins tapestries for the French King Louis XIV.

Harmen Jansz Muller, Hunt for Ibex, 1570, engraving after Stradanus (Jan van der Straet), 32.5 x 44.5 cm (Yale University Art Gallery)

For instance, Harman Jansz. Muller made prints that belonged to a larger series of hunting scenes set into ornamental frames that look like the biombo: the frames have flowers, swags, and animals. They likewise show hunters in landscapes pursuing animals. Interestingly, these printed images were themselves based initially on tapestry designs made by Stradanus for Duke Cosimo de’ Medici’s villa outside of Florence. These became so popular that Stradanus (in collaboration with Philips Galle), made even more hunting scenes as engravings—all of which proved immensely popular throughout Europe.

Left: garland, heads, and swag. Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: ox head and garland. Ara Pacis Augustae (Altar of Augustan Peace), 9 B.C.E. (Ara Pacis Museum, Rome, Italy) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Stradanus’s hunt scenes drew on ancient Greco-Roman textual sources including Pliny, Homer, and Herodotus. They also borrow from classicizing imagery, such as the decorative frames, swag, garlands, and ox heads. Using motifs and scenes from prints that borrowed from classicizing court objects was yet another way of transforming the biombo into an elite court object that advertised its owner as a powerful intellectual.

The influence of Asia

There are yet more layers to this complex biombo—its very form as a folding screen and aspects of its visual appearance reveal Asian (especially Japanese) influences on the visual culture of New Spain. The word biombo comes from the Japanese “byobu,” which translates literally to “protection from wind” or “wind wall.”

Kano Motonobu, Birds and Flowers of the Four Seasons, 16th century, pair of folding screens, ink, color, and gold on paper, 162.4 × 360.2 cm each (Hakutsuru Fine Art Museum, Kobe)

These portable, freestanding objects functioned as room dividers—a function that continued when they arrived in New Spain. The first Japanese byobu arrived in Mexico City around 1614 as a diplomatic gift, immediately becoming popular in elite circles. This was the result of the embassy of the samurai Hasekura Rokuemon that stopped in New Spain on its way to Rome. By the 1630s, local recreations of Japanese folding screens developed.

Folding screen with view of the viceroy’s palace, c. 1675, oil paint and gilding (Museo de América, Madrid)

Goods from Asia were highly sought after luxury goods in New Spain, and as art historian Sofia Sanabrais notes, they spoke to a person’s refinement and education. When the Manila Galleon trade began after 1564 when Spain conquered the Philippines, new materials and goods began to flow across the Pacific Ocean to New Spain. In 1580, with the unification of Spain and Portugal, this also meant new access to Portuguese ports like Macau, Nagasaki, and Goa, increasing the global flow of goods. Oceans were the connective tissue not only between Asia and the Americas, but also the Americas and Europe. Importantly, the fascination with Asian objects from Japan (and other parts of Asia equally), and the local derivations of Asian goods, predates the phenomenon we now call Japonisme and Chinoiserie by centuries—these are often associated with the 18th and especially the 19th century.

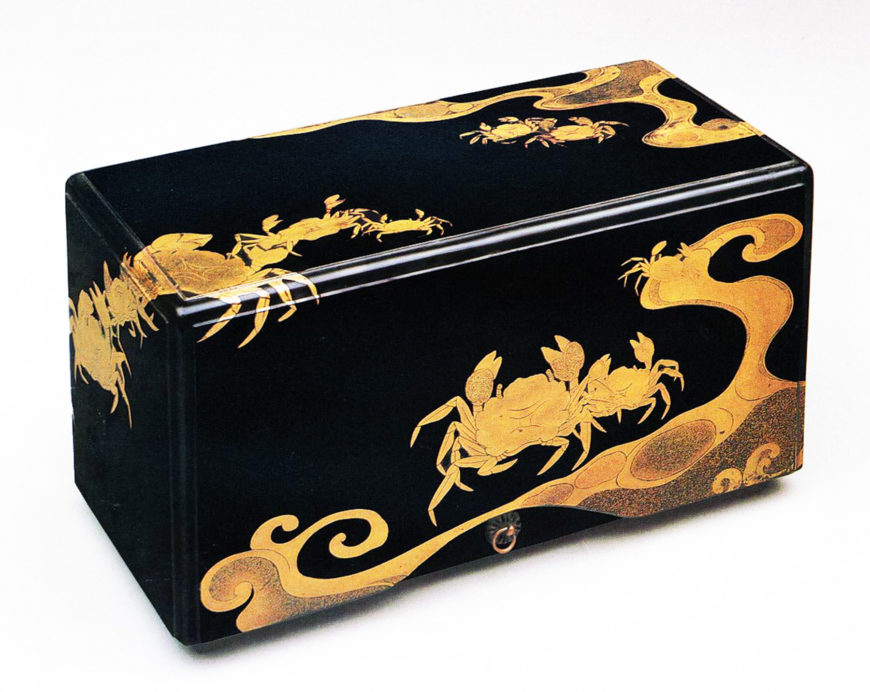

Box of Five Trays with Crabs and Waves, 17th century, Edo Period, gold on black lacquer, Japan, 31.8 x 17.1 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Batea, 1600–1700, Peribán (Mexico), Mexican lacquer on wood, H. 8 cm, diameter, 56.5 cm (Hispanic Society of America)

Portions of the biombo, especially the floral decorations above the arches at the top and the decorative bands at the bottom, look similar to smaller portable Asian lacquer objects, also traded in New Spain. If we compare a Japanese black lacquerware to the biombo, especially the decoration on the bottom, we can see how they are visually similar. The biombo’s delicate golden decorations set against a black background parallel the types of lacquered objects from Asia that came to New Spain.

Local lacquer working traditions already existed in New Spain. These traditions predated the invasion of Europeans, and with the infusion of Asian objects into New Spain, artists still working in these Indigenous traditions began to incorporate Asian motifs and color schemes. Like the folding screen’s adaptation and emulation of Japanese screens and aesthetics, New Spanish lacquerware also looked to Japanese objects for inspiration.

Left: Japanese artist, missal, 1580–1620, wood, lacquer, gold & shell, 35 x 31 cm (Peabody Essex Museum, MA); right: details of Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), c. 1697–1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Sometimes Asian lacquered objects also included gold, silver, and tortoise-shell inlay (sometimes called Namban (or Nanban) art), and they in turn—like the biombo—were adapted in New Spain. With the biombo, we see the clear influence of Namban objects on the decorative frame filled with flowers and shell. Importantly though, while the overall aesthetic hearkens to Asian lacquerware and Namban objects, many of the flowers are ones associated with Europe, such as tulips, lilies, and carnations. This is yet another powerful reminder that artists were not trying to faithfully copy artworks from any one tradition, but to adapt and transform to create something new.

Miguel González, The Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe), c. 1698, oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl (enconchado), canvas: 99.06 × 69.85 cm / frame: 124.46 × 95.25 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Shell-working (enconchado)

As far as we know, this biombo is one of the few that exists to combine a folding screen with enconchado (or shell inlay). Around 1660, enconchado paintings became popular in New Spain, such as we see in a painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe by Miguel González, and many of these paintings survive. Visually, the enconchado in the biombo and in other paintings enlivens the surface, drawing our eye to those areas that reflect light.

As already mentioned, the use of shell-inlay was common in Japanese Namban works. But shell-working and shell-inlaid objects also had a long-standing tradition in what is today Mexico. Numerous objects throughout Mesoamerica’s long history included shell, such as sculpture, disks, beads, pendants, bracelets, and more. The way the shell is incorporated into the biombo, while visually refers to Namban lacquer works, draws on techniques already present in New Spain, and reminds us that it is important to remember the role that Indigenous knowledge bearers (including artists and craftspeople) often played in the formation of New Spanish visual culture.

Courtly artists . . . from Asia?

Miguel González, The Conquest of Mexico, Tabla XX (detail), late 17th century, organic pigments, ink, stucco, nacre, and organic varnish on scrim panel, 52 x 100 cm (Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes de Buenos Aires)

While we are not certain who made this biombo, we do know that some of the most well-known enconchado painters, such as Juan and Miguel González, worked at the viceregal court—and made paintings for Sarmiento de Valladares, including scenes of the Conquest of Mexico sent back to Spain. For this reason, the biombo is attributed to the González Family circle.

It has been suggested that the González brothers may originally be from Asia. We know that many people from Asia came to New Spain beginning in the late 16th century, and this included artists, craftsmen, sailors, and more. [2] It can be challenging however to identify how many as they often changed their names upon arrival and when they converted to Christianity.

Challenging categories

The Brooklyn Biombo speaks to the challenges with existing categories that art historians tend to use, helping us to question and reconsider how we locate, discuss, and frame objects. It also reveals the many types of art forms, ideas, and places that the biombo engages: tapestries, prints, paintings, and shell-work; ancient Greco-Roman sources, conquest narratives, and battle stories; and the locations of Spain, Florence, Antwerp, Versailles, Holland, the Philippines, Japan, and, of course, Mexico City and New Spain more broadly.