Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), c. 1697-1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Portraits, furniture, silver, textiles, folding screens, metal basins, devotional objects, and ceramics. These are among the many types of objects commissioned or purchased by elites in the Spanish viceroyalty of New Spain. While the Church was the most important patron of the arts in New Spain, it was not the only patron of luxurious artworks. Colonial aristocrats, such as peninsulares (Spaniards born in Spain) or criollos (Spaniards born in the viceroyalties), worked as viceregal officials, merchants, or plantation owners. The artworks decorating their homes showcased their wealth and status in viceregal society. While these were initially imported from abroad, local artists eventually created them at home—as in the case of the biombo, a folding screen traditionally used in Asia.

Juan Correa, Folding screen showing the meeting of Hernán Cortés and Moctezuma II, c. 1675, oil and gilding, 199 x 556 cm (Museo Soumaya, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Biombos

The biombo became a common feature of aristocratic households in colonial Mexico. An example of a seventeenth-century double-sided biombo by the renowned Afro-Mexican painter Juan Correa depicts a historical narrative on one side, and an allegorical one on the other. The Encounter of Cortés and Moctezuma II, painted across ten panels, depicts the fateful encounter between the Mexica (more commonly known as the Aztecs) and Spaniards. At right, Cortés enters on horseback, while Moctezuma sits under a canopy as his attendants carry him.

Juan Correa, Folding screen showing Moctezuma II on a litter (detail), c. 1675, oil and gilding, 199 x 556 cm (Museo Soumaya, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Illustration of the the Toxcatl Massacre, from Diego Durán, The History of the Indies of New Spain, 1579 (Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid)

The rank of both men is communicated through their position in the composition, as well as through dress. Cortés wears rich fabrics and a feathered helmet, while Moctezuma II wears an elaborate crown and holds a scepter. Correa depicts both men as equals, despite the inherent inequality and brutality of the Spanish conquest. Different from scenes depicted in some sixteenth-century codices, like the Toxcatl Massacre from Diego Durán’s Historia de las Indias de Nueva España e islas de la tierra firme (1579), Correa depicts a somewhat positive view of this encounter.

Juan Correa, Folding screen showing an allegory of the Four Continents, c. 1675, oil and gilding, 199 x 556 cm (Museo Soumaya, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

On the other side of the biombo is a depiction of the allegorical representations of Africa, Asia, America, and Europe. Correa draws particular attention to the continents of Asia and Europe, placed prominently at center and flanked by Africa at right and America at left. In using the identifiable portraits of the Spanish King Charles II and his first wife, Marie Louise of Orleans, dressed with the French royal fleur-de-lis (to represent Europe), Correa singles out this continent from the other parts of the world.

Juan Correa, Folding screen with allegory of America (left) and Europe (right and center), c. 1675, oil and gilding, 199 x 556 cm (Museo Soumaya, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Charles II turns his back on America and points his toes towards the text at bottom, which reads “Europa.” This gesture alludes to how Charles II “has triumphed over America,” and as a result, he can now gaze confidently and “with desire toward Asia and Africa.” [1] If this is the case, then the biombo depicts somewhat contradictory stories. The Encounter of Cortés and Moctezuma II focuses on equality and autonomy, but The Four Parts of the World showcases Europe’s global aspirations, an image that is more in line with the imperialist behavior of the period—and indeed with the colonization of Mexico.

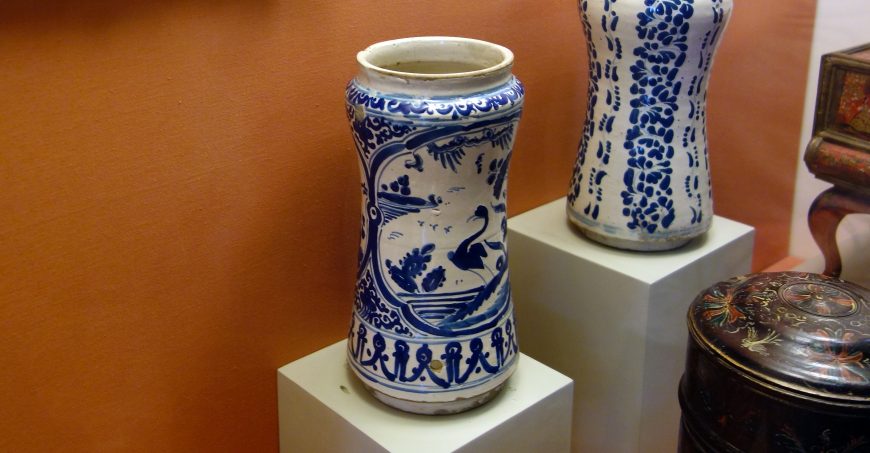

Talavera poblana vessel, 17th century, earthenware (Franz Mayer Museum, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Ceramics

Mexican nobility also decorated their homes with ceramics. These could be made locally or imported from Asia, Europe, or the viceroyalty of Peru. The importation of Chinese porcelain and Dutch delftware created a demand for blue-and-white ceramics, and a local tradition emerged in New Spain. The city of Puebla de los Ángeles, the second largest city of the viceroyalty, specialized in this type of ware, known as talavera poblana (Spanish for “poblano earthenware”). Talavera poblana creates this color combination through a technique known as tin glazing. The tin-covered surfaces of vessels take on a white glossy appearance when fired. The blue decorative patterns that make up the landscape and other imagery are also painted with metal oxides that turn blue when fired.

Covered jar (búcaro), ca. 1675–1700, earthenware, burnished, with white paint and silver leaf, 70.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

In Spain, and throughout Europe, aristocrats coveted another type of earthenware, known for its distinctive aroma and supposed medicinal qualities. These ceramic vessels, known as búcaros de Indias, originated in Mexico, and indeed one can be seen in Velázquez’s famous Las Meninas (on a tray being offered to the young infanta), a reflection of the transatlantic nature of the global art trade during Spanish colonialism.

Francisco Clapera, set of sixteen casta paintings, c. 1775, 51.1 x 39.6 cm (Denver Art Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Casta paintings

Spaniard and Indian Produce a Mestizo, attributed to Juan Rodríguez Juárez, c. 1715, oil on canvas (Breamore House, Hampshire, UK)

Local artistic production in the form of biombos, talavera poblana, enconchados, and casta paintings were also popular Spanish exports. Casta paintings consisted of multiple canvases that documented the phenomenon of racial mixing in New Spain, while at the same time ranking each casta (Spanish for “caste”) into a particular hierarchy.The purpose of these casta paintings is not entirely known. It is also unclear the extent to which they accurately depict colonial reality, but they nevertheless reveal an important insight into the crafting of identity through race in the Viceroyalty of New Spain.

Casta paintings tried to document and categorize what the eighteenth-century Archbishop of Mexico, Francisco Antonio Lorenzana, identified as a complex phenomenon. He explained in 1770: “Two worlds God has placed in the hands of our Catholic Monarch, and the New does not resemble the Old, not in its climate, its customs, or its inhabitants. . . . In the Old Spain only a single caste of men is recognized, in the New many and different.” [2] Spanish colonizers felt the need to document this racial diversity in New Spain, and initiated the tradition of casta painting as a way to understand this phenomenon. This was in line with the Enlightenment’s penchant for cataloguing information and fondness for encyclopedic knowledge.

Miguel de Herrera, Portrait of a Lady, 1782, oil on canvas (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Portraits

Painted portraits became increasingly popular in New Spain, especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Portraits such as Portrait of a Lady by Miguel de Herrera captured colonial aristocrats in the most favorable of conditions. Whether these paintings hung in private residences or public buildings their intent was to showcase to others the social standing, public service, family ancestry, or even the purity of the sitter (as in Portrait of a Lady). In emphasizing the delicate lace of her sleeves, the elaborate plumes and diamond ornaments on her hair, and the heavy jewelry that rests on her ears and around her neck, Herrera captures the elite status of the sitter. This is similar to how artists of casta paintings, such as Juan Rodríguez Juárez, communicate social rank through race, gender, dress, and accessories. The closed fan, which she holds prominently with her right hand, is not only a fashionable accessory, but also as an indicator of her virginity. It also points in the direction of her watch, a common symbol of mortality.

Miguel de Herrera, Portrait of a Lady (detail), 1782, oil on canvas (Museo Franz Mayer, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While portraits shed light on the racial and social relations in colonial Mexico, Portrait of a Lady changes the context of portraiture entirely, not only because the painting functions independently (not as part of a series), but also because the woman is depicted as an individual rather than a type (as in casta paintings). Additionally, the portrait depicts the woman with a distinct sense of agency and autonomy, which is in direct opposition with the depiction of types in casta paintings. The painting was most likely commissioned by her and therefore exhibited in the privacy of her home. Casta paintings, on the other hand, served an entirely different purpose in Spain, where they were considered quasi-documentary proof of the exotic people, costumes, and fruits of the colonies.

Crowned Nun Portrait of Sor María de Guadalupe, c. 1800, oil on canvas (Banamex collection, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Nun portraits

A distinct and original genre of portraiture in New Spain are crowned nuns (monjas coronadas), which became recognizable manifestations of the viceroyalty’s tendency for exuberance in religious matters. These portraits were painted to commemorate nuns’ admissions into the convents (and in some cases, their deaths). The extravagant crowns that characterized these portraits represented the wearer’s historical importance within the context of their indissoluble marriage to God and the Church.

Escudo de Monja (detail) in the Crowned Nun Portrait of Sor María de Guadalupe, c. 1800, oil on canvas (Banamex collection, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

These portraits displayed another typically New Spanish nun accessory, the nun’s shield (escudo de monja), a kind of badge that was worn as part of their habit. These shields were round medallions portraying devotional images chosen for their affinity to the wearer. Following particular formulaic conventions, the most important painters of New Spain contributed in making these profession portraits a very original form of artistic production. These portraits were often commissioned by the nuns’ families, who would display them proudly in their elite homes.

Together, these portraits—whether of castas, aristocrats, or nuns—demonstrate the currency of social portraiture in New Spain, and the importance of capturing religious and material wealth, and establishing racial and gender hierarchies.

Notes:

[1] Michael Schreffler, The Art of Allegiance: Visual Culture and Imperial Power in Baroque New Spain (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2007), 123

[2] Cited in Ilona Katzew, Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico (Hew Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 39

Additional resources

Read more about the Brooklyn Biombo

Read about the Biombo with the Conquest of Mexico and View of Mexico City

Read more about Crowned Nun Portrait of Sor María de Guadalupe

Read about the large market (called the Parián) in the Plaza Mayor (or Zócalo) of Mexico City