Miguel González, The Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe), c. 1698, oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl (enconchado), canvas: 99.06 × 69.85 cm / frame: 124.46 × 95.25 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

The Virgin of Guadalupe reveals herself to Juan Diego

On December 9th, 1531, a decade after the downfall of Tenochtitlan and the beginnings of Spanish colonization, a man named Juan Diego (born Cuauhtlatoatzin) was walking across the Hill of Tepeyac near a razed shrine to the Mexica (Aztec) earth goddess Tonantzin when a woman appeared and spoke to him in Nahuatl, his native tongue. She revealed herself as the Virgin Mary, and asked Juan Diego to go to the local bishop, Juan de Zumárraga, and ask for a church to be built on the hill in her honor. Bishop Zumárraga did not believe Juan Diego’s story. The Virgin Mary revealed herself to Juan Diego two more times with the same request, but still no shrine was constructed. During her fourth request on December 12th, she told Juan Diego to gather roses from the hill into his cloak (or tilma). When he stepped before the bishop and opened his cloak, the roses—Castillian roses (which are not native to Mexico) spilled forth. Imprinted on the tilma was an image of the Virgin Mary herself, known today as the Virgin of Guadalupe. Zumárraga recognized the miracle, and a shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe was built on the Hill of Tepeyac, with a basilica to her constructed below. Today, the original miraculous tilma image hangs in the new basilica at Tepeyac in Mexico City.

Another painting of the Virgin of Guadalupe, late 17th century, 190 cm high, oil paint, gilding, and mother of pearl on panel (Franz Mayer Museum, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Devotion to the Virgin of Guadalupe increased dramatically in Mexico during the seventeenth century with the publication of books printed in her honor and greater support from the creole population. One of the earliest books recording the apparitions was the Nican mopohua, written in Nahuatl in the sixteenth century and widely distributed in the following century. Creoles began to identify with an “American” or Mexican identity, and supported the Virgin of Guadalupe as a uniquely americano miracle. After all, she had revealed herself on Mexican soil to a Nahua (indigenous) man. With her increased popularity came a demand for more images, especially those that faithfully copied the original miraculous tilma (as in the painting above in the Franz Mayer Museum). Many paintings even include the phrase fiel copia, or “true copy,” to suggest their painting is a direct copy of the tilma image.

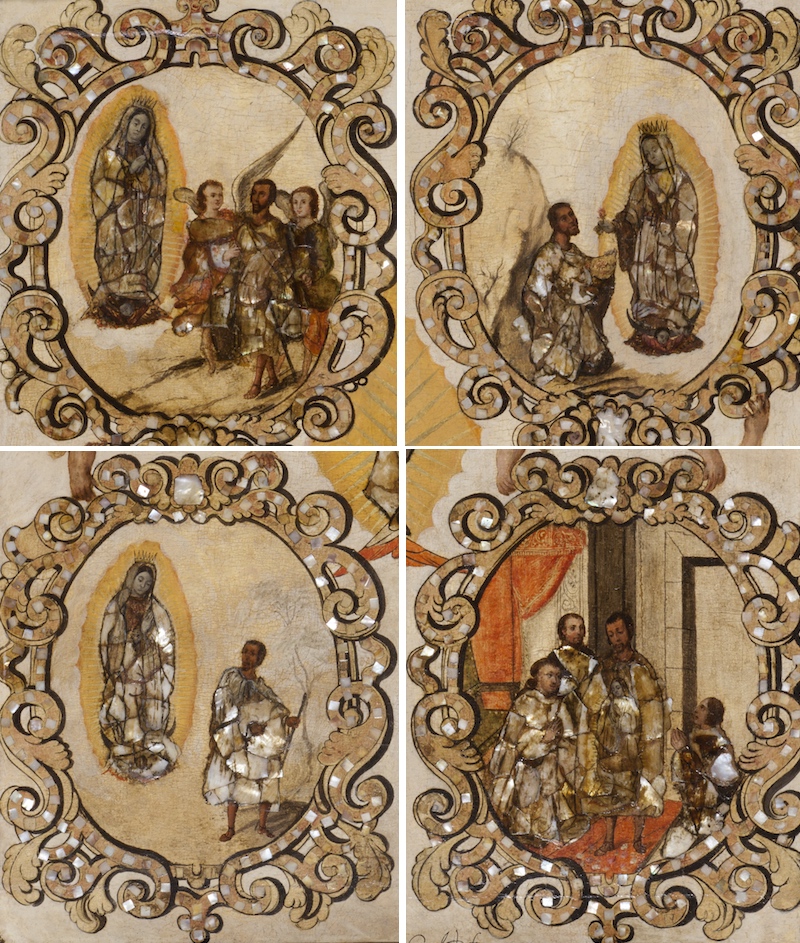

Detail, Miguel González, The Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe), c. 1698, oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl (enconchado), canvas: 99.06 × 69.85 cm / frame: 124.46 × 95.25 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Miguel Gonzalez’s enconchado painting

Some of the most remarkable images of the Virgin of Guadalupe are created not entirely in paint, but also include mother-of-pearl, or enconchado. Miguel González’s version portrays the Virgin as she appears on the tilma: in three-quarter view, crowned, hands clasped, eyes cast downwards, encased in light, and standing on a crescent moon that an angel supports. The manner in which the Virgin of Guadalupe appears relates to Immaculate Conception* imagery which was based on Revelation 12: “clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet and a crown of twelve stars on her head.”

Angel (detail),Miguel González, The Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe), c. 1698, oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl (enconchado) (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

In the four corners of the painting (below) we see four framed scenes carried by angels. These represent different moments in the story of the miracle.

Four corner scenes (detail), Miguel González, The Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe), c. 1698, oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl (enconchado), canvas: 99.06 × 69.85 cm / frame: 124.46 × 95.25 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

In the upper left, Juan Diego is led to the Virgin Mary by angels. In the upper right, Juan Diego has a vision of the Virgin Mary at the Hill of Tepeyac; in the lower left, Juan Diego takes leave of the Virgin Mary with a full cloak, and in the lower right Juan Diego reveals the miraculous image on his cloak to the bishop and others.

González uses pieces of mother-of-pearl shell to form most of the Virgin Mary’s clothing (it even decorates the bodies of the angels and the frames they support). The iridescent shell would reflect shimmering candlelight to emphasize the sacredness and importance of the Virgin Mary.

Holy Spirit symbolized by a dove (detail),Miguel González, The Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe), c. 1698, oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl (enconchado), canvas: 99.06 × 69.85 cm / frame: 124.46 × 95.25 cm (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Above the Virgin of Guadalupe is the dove representing the Holy Spirit in a golden cloud, and below an eagle perches on a cactus. You might be familiar with this symbol from the Mexican flag, which refers to the Mexica (or Aztec) and the mythic founding of their capital city, Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City). On their journey from their homeland (Aztlan), the Mexica patron deity Huitzilopochtli (pronounced “wheat-zil-oh-poach-lee”) informed the Aztecs that they would know when to end their journey and establish a new home when they saw an eagle perched on a cactus (the snake got added to the story later), which happened to be on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco (today, under Mexico City).

By the seventeenth century, when creoles were looking for ways to emphasize New Spain’s greatness and uniqueness, the symbol of the eagle on the cactus once again became popular as a symbol for Mexico City. Its inclusion here—as well as in many other artworks—signals the Virgin of Guadalupe’s direct connection to the people of New Spain, and so connects her to the creoles as well.

Ladder (detail), González, The Virgin of Guadalupe (Virgen de Guadalupe), c. 1698, oil on canvas on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl (enconchado) (Los Angeles County Museum of Art)

Beyond the elaborate use of mother-of-pearl, González also created a frame that includes more pieces of shell inlaid into wood. Floral decorations in red and gold alternate with common symbols of the Virgin Mary that derive in part from the Song of Songs and other Old Testament sources. We see a ladder, palm tree, ship, lily, and fountain. The ladder connoted Jacob’s Ladder or the ladder to Paradise (think of Mary as the ladder by which her son descended to earth and by which mortals will ascend into heaven), while the palm tree signified an Exalted Palm (as recounted in Ecclesiasticus 24:14) and also the righteous and chosen ones (mentioned in Psalm 92:12). Mary is seen as the ship of salvation, but the ship could also refer to Noah’s Ark. The lily refers to Mary’s purity (she is the lily among the thorns), and the fountain refers to Mary as “the fountain of living water” (Jeremiah 17:13).

Enconchado

Enconchado artworks were popular in seventeenth-century Mexico. The shell is placed into the painting like mosaic, then covered with glazes. Shell-working had been an important art form among some Mesoamerican peoples. In the Florentine Codex, we see illustrations of Mexica shell workers, and discussions of the types of shell used in different types of objects.

Some scholars have noted the connection between enchonchado and Japanese namban lacquer work that uses a similar technique with shell inlaid into wood. Many namban lacquer works also show a preference for red and gold colors, like we see on our Mexican enconchado painting.

Storage Box in Nanban style, 16th century (Japan), gold maki-e on black lacquer, inlaid with mother-of-pearl; silver mounts, 14 x 32.1 x 28.9 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Japanese goods were imported to Mexico via the Manila Galleons, where they were sold or sent on to Spain. Eventually, non-Japanese artists began to copy the Japanese technique.

Folding Screen with the Siege of Belgrade (front) and Hunting Scene (reverse), c. 1697-1701, Mexico, oil on wood, inlaid with mother-of-pearl, 229.9 x 275.8 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Other types of Japanese objects, like folding screens (called biombos, example above), also became popular. It has been suggested that after Japan cut ties with foreigners in the seventeenth century, the demand for Japanese goods (or Japanese-inspired goods) increased. We even have an example of a Mexican enconchado folding screen that is based on Japanese folding screens and namban lacquer works, but uses imagery borrowed from European prints and tapestries. The desire for Japanese objects is likely one reason for the popularity of enconchado paintings like González’s Virgin of Guadalupe, and they showcase the cosmopolitan nature of colonial Mexican society.

*See the essay on Miguel Cabrera, Virgin of the Apocalypse for more on immaculate conception iconography.