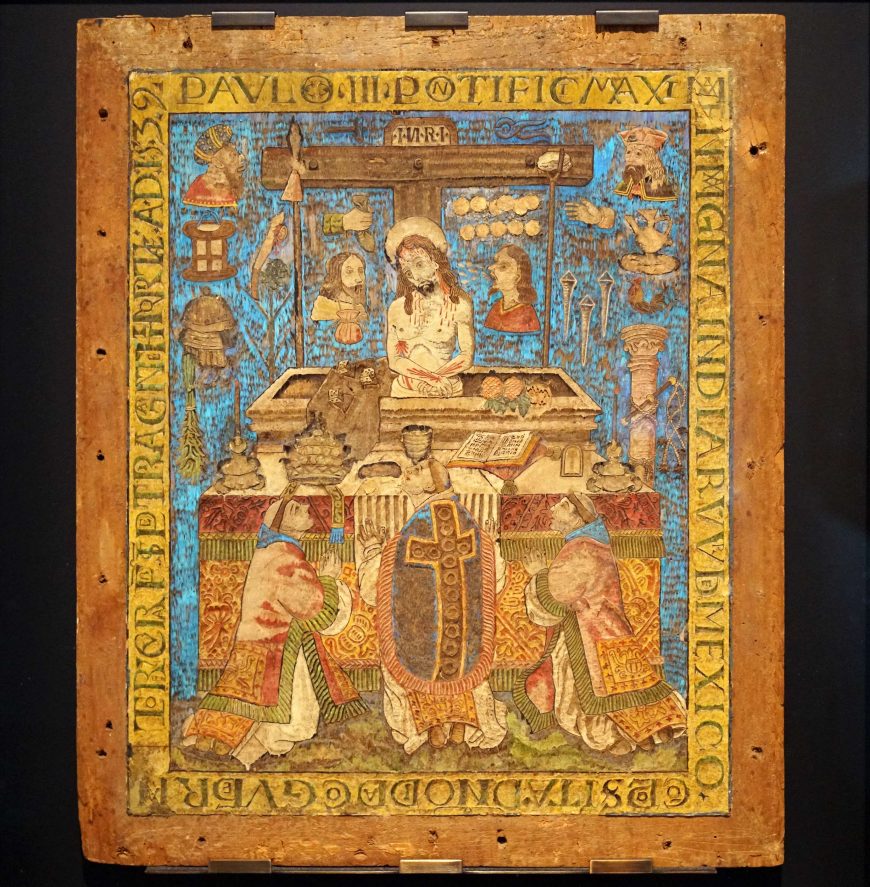

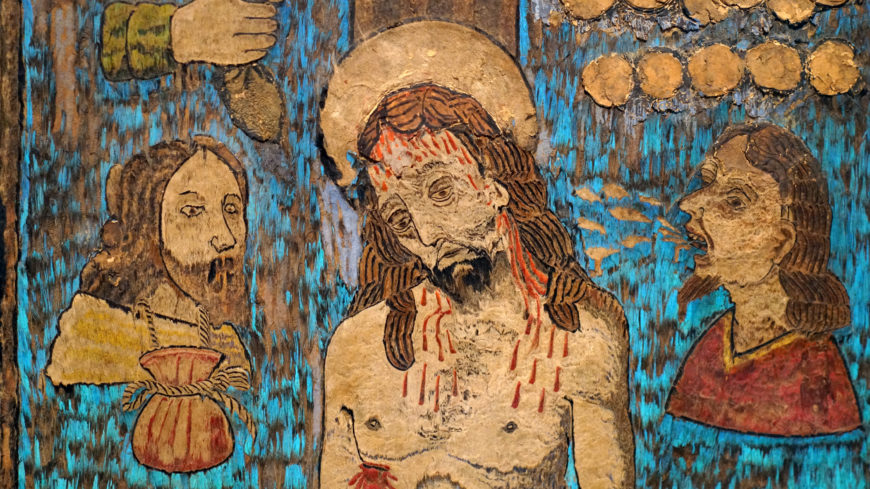

The Mass of St. Gregory, 1539, feathers on wood with touches of paint, 26-1/4 x 22 inches / 68 x 56 cm (Musée des Amériques, Auch; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Imagine a two-dimensional artwork made of feathers instead of paint, pen, or pencil. The feathers rustle with the breeze or as you exhale, their iridescent qualities creating a luminous effect as you turn the artwork in your hands or lift it upwards. Feathered artworks were created in Mesoamerica before and after the Spanish Conquest in 1521, with Spaniards and other Europeans marveling at their shimmering beauty and originality.

A clash of traditions

In 1539, the Nahua noble and gobernador (governor) of Mexico City, Diego de Alvarado Huanitzin (nephew and son-in-law to Moctezuma II, the last Aztec ruler before Spanish colonial rule began in 1521), commissioned a featherwork for Pope Paul III showing the Mass of St. Gregory. This artwork, made of different types of bird feathers attached to a wood panel, is remarkable for several reasons. Not only is it the oldest surviving featherwork from colonial Mexico, but it was made by an Indigenous man in order to be sent to the Pope during the early period of Spanish colonization. Two years before the featherwork’s creation, Pope Paul III had issued the bull Sublimus Dei that decreed Amerindian peoples to be rational human beings complete with souls, and called for an end to their enslavement.

The Mass of St. Gregory, 1539, feathers on wood with touches of paint, 26 1/4 x 22 inches / 68 x 56 cm (Musée des Amériques, Auch; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The subject of the Mass of St. Gregory was popular at this time because of its focus on transubstantiation—the belief that the bread and wine transform into the body and blood of Christ during Mass. Saint Gregory was an important 6th-century pope, and one day during Mass he raised the consecrated host (the bread) and experienced a miraculous vision of Christ on the altar. His vision offered proof that the bread literally became Christ’s body when consecrated. Christ appeared to Saint Gregory as the Man of Sorrows—a type of image of Christ, where he is shown above the waist, with his wounds displayed on his hands and side.

The featherwork production of The Mass of Saint Gregory was likely supervised by the famous Franciscan missionary, Pedro de Gante, who came to the Viceroyalty of New Spain (the Spanish colonies in North America) from Flanders to aid in converting the native peoples to Christianity. He established a well-known school that trained Indigenous men in European artistic conventions and techniques. Prints were often supplied as models for these Christian neophytes. The featherwork represents the clash of different worlds—its technique is Mesoamerican, but the subject is European and Christian.

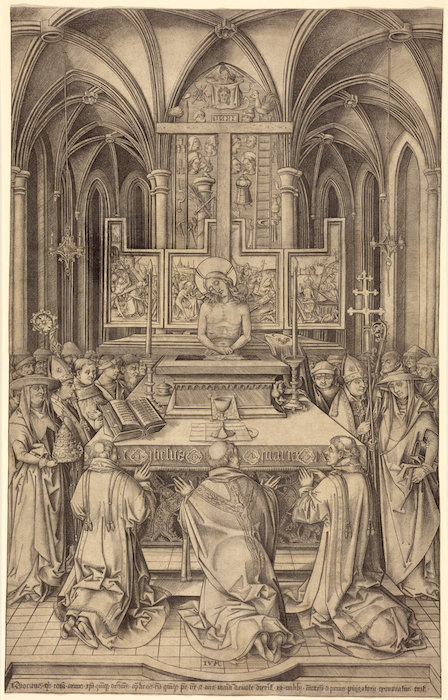

Indigenous artists of early colonial Mexico learned about European artistic techniques and Christian subject matter in schools attached to conventos (missionary centers). Mexico City had some of the most famous, including the School of San Jose where Pedro de Gante worked. Some of the most common models supplied to the students were prints brought from Europe. The Mass of St. Gregory featherwork compares to Israhel van Meckenem’s The Mass of St. Gregory, c. 1490—suggesting the print came to New Spain and provided a model for the 1539 featherwork.

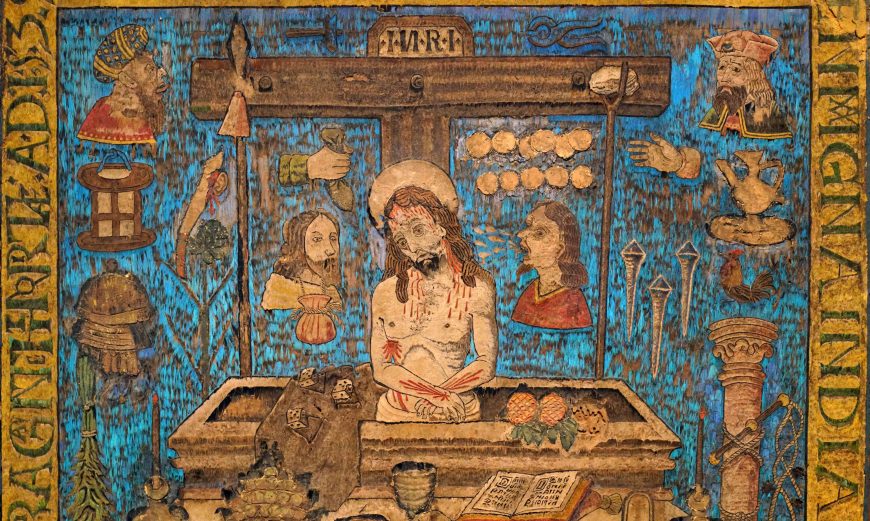

The instruments of the Passion of Christ (also known as the Arma Christi— specifically the instruments of Christ’s suffering, including the column, nails, sponge, cock, and flagellant whip) appear on or surrounding the altar in both van Meckenem’s print and the featherwork. Other colonial Mexican artworks—especially those used to aid in conversion of Indigenous populations—displayed passional instruments. On atrial crosses (crosses found in the courtyards, or atria, of missionary churches), for example, friars could point to the different Arma Christi as they taught native peoples about Christian dogma and biblical history.

Featherworks

Featherworks were among the most highly prized objects in the early post-Conquest period. Hernan Cortes sent feathered objects to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V to dazzle him with their richness and unique qualities. Others, like Diego de Soto, carried packages of featherworks from New Spain to Spain to give to Charles V soon after the Spanish Conquest. Many featherworks found their way into cabinets of curiosities throughout Europe, no doubt collected because they symbolized the exotic “New World” across the Atlantic. Still today, feathered goods like the so-called Headdress of Moctezuma are some of the most prized possessions of European museums.

Detail, Codex Mendoza, folio 46r (Bodleian Library, Oxford). The text records feathers paid as tribute (from top to bottom and left to right: “four pieces of rich feathers, made like handfuls into this form,” “eight thousand little handfuls of rich turquoise feathers,” “eight thousand little handfuls of rich red feathers” and “eight thousand little handfuls of rich green feathers.”

We find many Indigenous groups used feathers to adorn luxury goods, festoon clothing, and function within ceremonies. The Mexica (more commonly known as the Aztecs), were among those groups who prized feathers. Through long-distance trade, the Aztecs acquired feathers from afar. The most highly prized feathers—those of the resplendent quetzal—came from Guatemala. Hummingbirds, macaws, and many other birds supplied feathers. The Mexica also collected feathers as tribute from areas they conquered. Tribute lists illustrated in the Codex Mendoza, produced after the Spanish Conquest, demonstrate the large number of birds and feathers sent to the Aztec capital city, Tenochtitlan. In Tenochtitlan, featherworkers comprised their own special social class. They lived in a neighborhood called Amantla, which is why they were called amanteca.

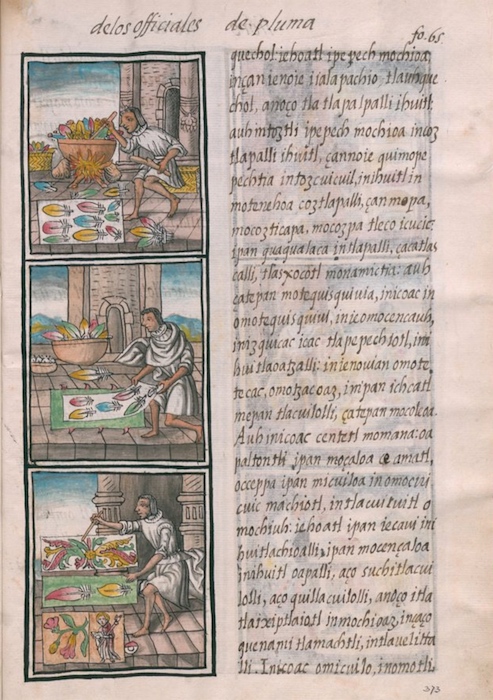

The amanteca and their featherworks were both valuable, as indicated by the attention paid to them in the encyclopedic Florentine Codex, produced by the Franciscan friar Bernardino de Sahagun and his Indigenous collaborators between 1577–79. The Codex devotes many pages to the amanteca and provides numerous illustrations detailing how they worked, including how they glued feathers to flat surfaces.

The Mass of St. Gregory (detail), 1539, feathers on wood with touches of paint, 26 1/4 x 22 inches / 68 x 56 cm (Musée des Amériques, Auch)

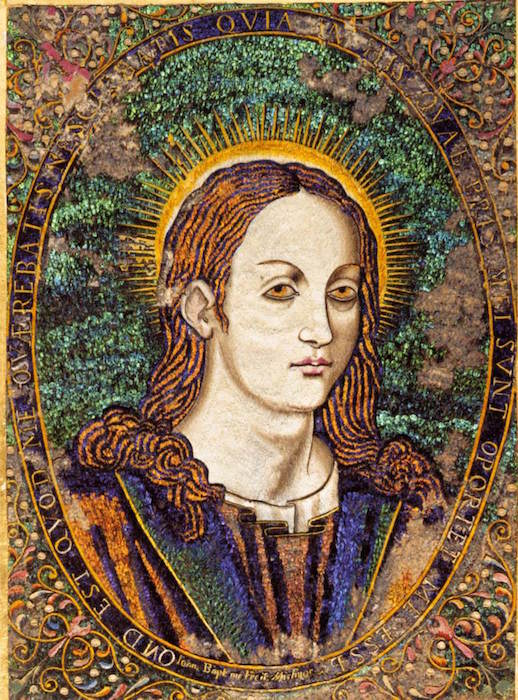

Divine Light

As religious or devotional objects, iridescent featherworks like The Mass of St. Gregory seemed to communicate ideas about divine light. As air passed over their surface, the feathers rustled and moved, animating the object with a life force. Depending on how you held the object, the colors of the feathers seemed to transform as well. Green hummingbird feathers became purple or pink, corresponding to Christian notions of divine light. The iridescent qualities of feathers and their Christian symbolism compare to stained glass windows in Gothic cathedrals, all of which relate to Christ as the lux mundi (the light of the world).

Juan Bautista Cuiris, Portrait of Christ, Hummingbird and Parrot feathers (Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna)

The potential religious connotations of featherworks stimulated the creation of liturgical garments and objects made of feathers. Examples of bishops’ garments (like miters and stoles) and eucharistic altars still exist. Many of the liturgical garments were sent to Europe in the sixteenth century. We know, for instance, that Ferdinando I de’ Medici, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, actively collected featherworks and other items from colonial Mexico.

Sacred Eucharistic Featherwork, 16th century, feathers on wood with silver trimmings, 55.7 x 37.2 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Several sixteenth-century eucharistic triptychs portray the Last Supper flanked by saints Peter and Paul. The central panel also includes a Latin inscription that relates the moment when Christ offers his body and blood—the very same words a priest would say during Mass at the moment of transubstantiation.

Additional resources:

“The Mass of St. Gregory,” in Painting a New World, exh. cat., ed. Donna pierce, Denver Art Museum (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2004), pp. 98–102 (available online).

Claire Bergeaud et Frédérique Vincent, “Feather Stories: The Saint Gregory Mass and the Ecouen Triptych,” Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos, Colloques, mis en ligne le 25 janvier 2006.

Teresa Castelló Yturbide and Manuel Cortina Portilla, The Art of Featherwork in Mexico (Mexico: Fomento Cultural Banamex, A.C., 1993).

Joanne Pillsbury, Timothy F. Potts, and Kim N. Richter, eds., Golden Kingdoms: Luxury Arts in the Ancient Americas (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2017), no. 226, p. 270.

Alessandra Russo, Gerhard Wolf, and Diana Fane, eds., Images take flight: Feather art in Mexico and Europe 1400–1700 (Munich: Hirmer, 2015).

Maya Stanfield-Mazzi, Clothing the New World Church: Liturgical Textiles of Spanish America, 1520–1820 (University of Notre Dame Press, 2021).