Church of Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, 1751–58, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: Luidger, CC BY-SA 3.0)

In the early morning with the rising sun, the apricot-peach colored stone of the church of Santa Prisca and San Sebastián in Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico, seems to radiate with light. On a hill towering above the city around it, the church’s tall bell towers beckon people to enter its doors. The elaborate carvings on the façade and towers also seem to writhe with life. As shadows pass over the surface throughout the day, you could swear the building was moving. Imagine how striking it is to then enter the church and be completely overwhelmed with walls that vibrate with gold. This church perfectly embodies the architectural style that has been labeled “ultrabaroque,” which lasted from approximately 1720 to 1780 in the viceroyalty of New Spain. More specifically, it is an example of the complex, intricate churrigueresque style, which originated in Spain and was transformed in the Spanish Americas.

Ultrabaroque architecture in a silver mining town

The parish church of Santa Prisca and San Sebastián is a useful example to discuss ultrabaroque, churrigueresque architecture. While most churches from New Spain (as elsewhere) were built in stages over long periods of time (such as the Cathedral of Mexico City), this church was built in a short period of time and so fully embodies this style. The project was overseen by the architect Diego Durán Berruecos (though some sources claim the architect was Cayetano de Sigüenza) between 1751 and 1758.

Taxco was an important 18th-century silver-mining location and prior to colonization was a Nahua town. When miners found silver in 1716, the city of Taxco experienced a boom. One miner, José de la Borda, amassed an incredible fortune, and he commissioned new artistic projects, among them the Santa Prisca church. Like many Catholic Christians, Borda felt that paying for good works would shorten his time in Purgatory. Many churches have multiple patrons, so Santa Prisca and San Sebastián is also important because it was funded by a single major donor during his lifetime.

The façade

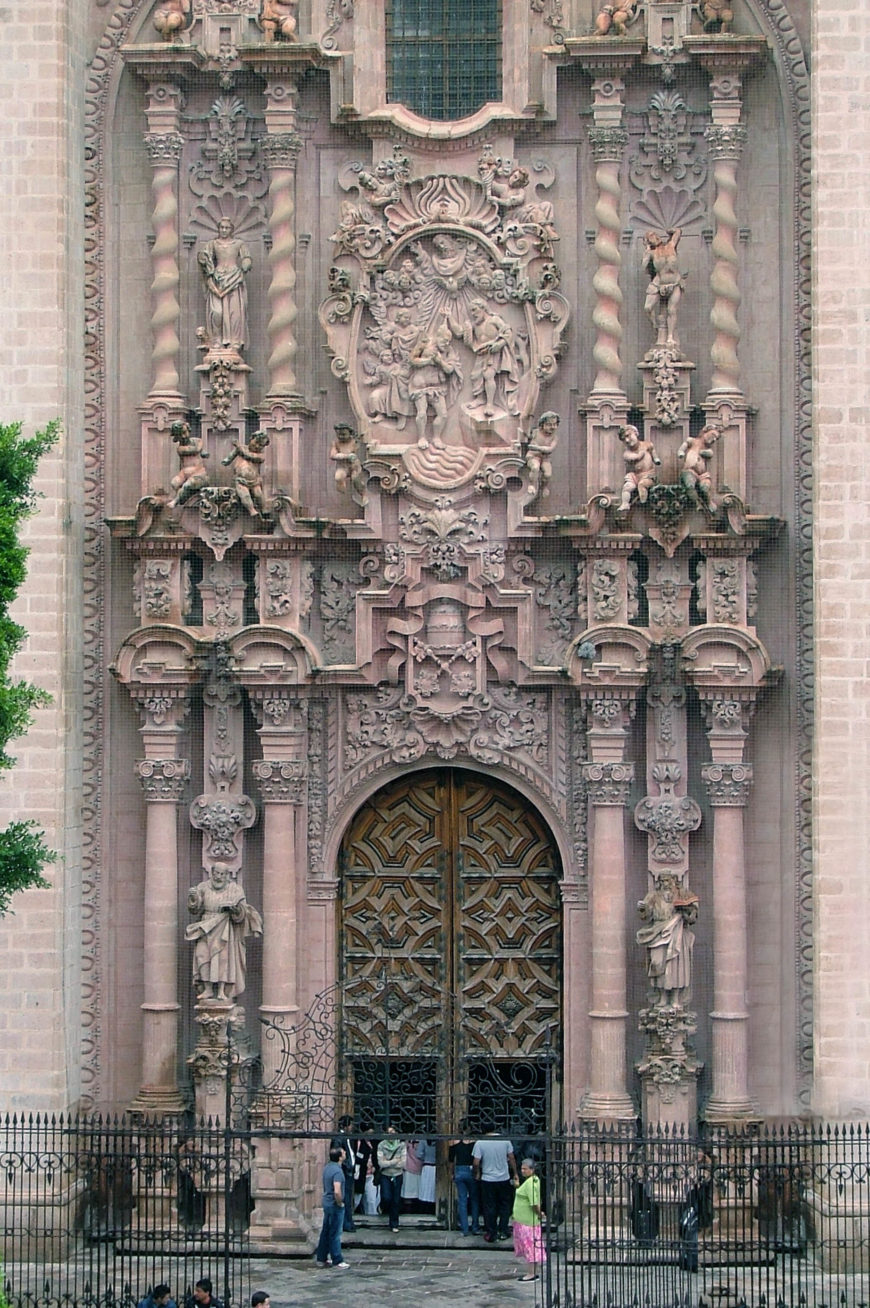

When standing in front of the church’s façade, it seems to stretch endlessly into the sky. If you take a step back, it is possible to make out the logic of the design. It is divided into three parts (what has been called an ABA construction). Two towers (A) flank a central portion (B); the towers are identical and mirror one another. The architect emphasized the verticality of the façade by placed it back from the towers, giving an impression that the towers squeeze the central section. This sense of compression leads our eyes upward.

Façade of the church of Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, 1751–58, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: Frankmx, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Retablo-façade of Santo Domingo Yanhuitlan, 16th century, Oaxaca (photo: Eduardo Robles Pacheco, CC BY 2.0)

The ornamentation of the façade also directs our eyes upward. The central section displays a riot of decoration, although all of it is in fact carefully composed. It looks similar to a retablo (altarpiece) that you might see within a church’s interior, and for this reason it is called a retablo-façade. A retablo was often divided into multiple levels with columns that framed sculptures and paintings. Retablo-facades originated in New Spain in the 16th century, with the construction of mission churches like Santo Domingo Yanhuitlan. Over time, the style of retablo-facades changed as the appearance of retablos themselves were transformed, from the more sober classicism we find at Yanhuitlan to the ultrabaroque-churrigueresque at Santa Prisca.

Niche-pilaster with Saint Paul, the church of Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, 1751–58, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: Frankmx, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Santa Prisca’s façade is organized into compartments on different levels. On the first level is a rounded arched doorway flanked by pairs of columns, which then flank a niche-pilaster. A niche-pilaster is a defining feature of ultrabaroque architecture in Mexico. It is a flattened squared column (a pilaster) on which is sculpture that appears to use the column as a niche. Here, the recessed pilaster is set deeper than the pair of solomonic columns that frame it. Sculptures of saints Peter and Paul (apostles of Jesus and founders of the See of Rome) appear on the niche-pilasters.

Detail of the façade of the church of Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, 1751–58, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: Elias Zamora, CC BY-SA 4.0)

On the second level an enormous rounded relief sculpture depicting the Baptism of Christ is flanked by pairs of Solomonic columns (columns that spiral and twist) that flank more niche-pilasters that contain the church’s patron saints, Prisca and Sebastian. Coats of arms, scalloped shells, scrolling vines, and putti fill in other spaces on the façade’s central section.

Belltower, Church of Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, 1751–58, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: AlejandroLinaresGarcia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Dome of the church of Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: júbilo haku, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The tops of the towers continue the riotous ornament found in the center, with estípite columns (another element associated with the ultrabaroque), engaged columns, grotesques, and other intricate ornament. Interestingly, the architect left the lower portion of the towers unadorned, only puncturing them with four windows framed in a scalloped, foliate design. This clever design forces your eye to ascend above the façade.

If you walk to the side of the church, this complex ornamentation disappears, but the large dome over the church’s crossing is now visible. Covered with shimmering polychrome tiles that have stars on them, the dome gives the impression of the heavens above the church. The tiles come from Puebla, a city further south that was famous for its glazed ceramic tile production.

Altars inside Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, 1751–58, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: Javier Castañón, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Inside the church

Santa Prisca has one of the few interiors that is original to the 18th century. Many churches were gutted and redone in a neoclassical style in the 19th century, so it is rare to experience one that is preserved. While the plan of the church is simple—a single nave with a transept (crossing)—the interior would never be described as simple.

Walking inside, visitors are immediately overwhelmed by the profusion of ornamentation. Stacked corinthian pilasters (in light pink) articulate the walls, and they have been rusticated to give a rougher design. We get the impression that they are multiplying before our eyes. While the walls are white/light pink, the retablos in the space are all in gold. Everything seems to vibrate before our eyes, making the space dynamic; it was designed to overwhelm congregants entering the church.

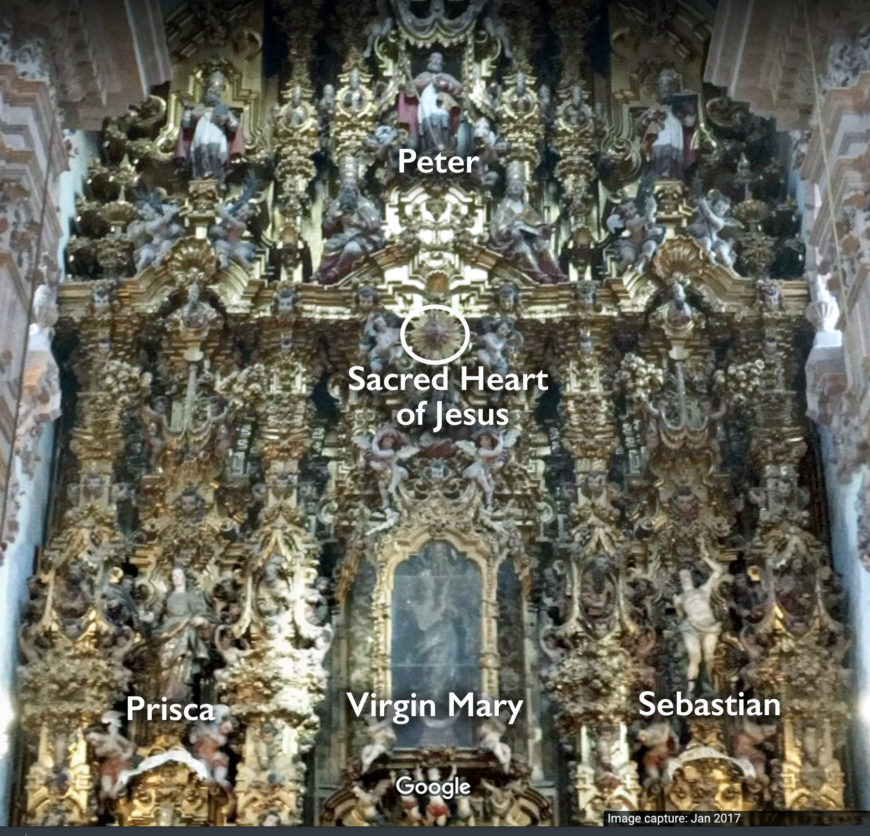

Isidore Vicente Balbás, Main altar inside Santa Prisca y San Sebastián, 1751–58, Taxco, Guerrero, Mexico (photo: Javier Castañón, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Jerónimo de Balbás, Altar of the Kings (Altar de los Reyes), 1718-37, Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary (Mexico City)

Twelve gilt retablos fill the space. The main retablo was produced by Isidore Vicente Balbás, son of Jerónimo who had created the main altar in the Cathedral of Mexico City, known as the Altar of the Kings. Isidore borrowed from his father’s design, creating an elaborate altarpiece that overwhelms the senses. Estípite columns form the retablos along with niche-pilasters.

Forms seem to dissolve, as if they are no longer solid, yet some figures are identifiable. At the center we see the Virgin Mary (behind glass), the Sacred Heart of Jesus above her, Saint Peter further above, and God the Father at the very peak. Other saints, including Prisca and Sebastian, are also noticeable. Paintings of varying sizes are found on most of the retablos, and they were made by some of the most important painters of the day—such as Cristóbal de Villalpando and Miguel Cabrera.

An exceptional church

The Church of Santa Prisca and San Sebastián may not have been located in a metropolitan city such as Mexico City or Puebla, but it expresses the fantastic wealth that some individuals amassed in New Spain. Also, because of its short construction time and excellent state of preservation, it is considered by many to be the best expression overall of the churrigueresque, “ultrabaroque” style that was popular in New Spain at this time. It seems to perfectly encapsulate Borda’s claim that “God has given to Borda and Borda gives to God.” [1]

Notes:

[1] Robert Mullen, Architecture and Its Sculpture in Viceregal Mexico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1997), p. 176

Additional resources

Learn more about the church from the World Monuments fund

James Early, The Colonial Architecture of Mexico (Southern Methodist University Press, 2001)

James Oles, Art and Architecture in Mexico (London: Thames & Hudson, 2013)

Ichiro Ono, Divine excess: Mexican ultra-baroque (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 1996)

Elisa Vargas Lugo de Bosch, La iglesia de Santa Prisca de Taxco (Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, Coordinación de Humanidades, Coordinación de Difusión Cultura, 1999)