Equestrian Oba and Attendants, 1550–1680, Nigeria, Court of Benin, Edo peoples, brass, 49.5 x 41.9 x 11.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Royal history rendered in brass

This remarkable brass plaque, dated between 1550–1680, depicts an Oba (or king) and his attendants from the Benin Empire—a powerful kingdom located in present-day Nigeria. We know that the central figure is an Oba because of his distinctive coral beaded regalia. Also, attendants hold shields above his head, either to protect him from attack or possibly from the hot, tropical sun. This was a privilege only afforded to an Oba.

The figures around him range in size, not because of their actual height or distance from the Oba, but rather due to their level of importance within the court. This convention of sizing human figures based on status is known as “hierarchic scale” and is found in artwork from cultures around the world and across time. The Oba would have traveled with a large cohort of attendants, warriors, servants, diplomats, chieftains, and priests.

The plaque originally hung alongside many others on posts throughout the palace of the Oba. The order of their placement on these posts would have told the history of the royal lineage of Benin’s Obas, who traced their dynasty all the way back to Oranmiyan, whose son was the first Oba of Benin. However, the sequence of plaques is lost to us since they were long held in storage when found by westerners in the 19th century. You may notice that the Oba rides sidesaddle on horseback, which would seem to indicate a connection to Oba Esigie (who ruled c. 1504–1550), the first Oba to travel by horse. However, without knowing the original order of the plaques, we will never know for certain whether this was Esigie or a later Oba who emulated his brash new mode of travel.

Equestrian Oba and Attendants (detail), 1550–1680, Nigeria, Court of Benin, Edo peoples, brass, 49.5 x 41.9 x 11.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Artists working in brass were organized under Esigie. Today, artists working in brass in Benin are part of a brass workers guild, and it was likely that previous generations would have also worked collectively. These artists created plaques and other sculptures using what is known as the “lost wax casting technique,” in which, first, a more malleable wax version of the final brass work is made. It is then covered in clay and fired to harden the clay, removing the wax, which melts away in the process (hence the term, “lost wax”). Hot, molten liquid brass is then poured into the clay mold. As the brass cools, it hardens, and the clay is removed, revealing the finished plaque.

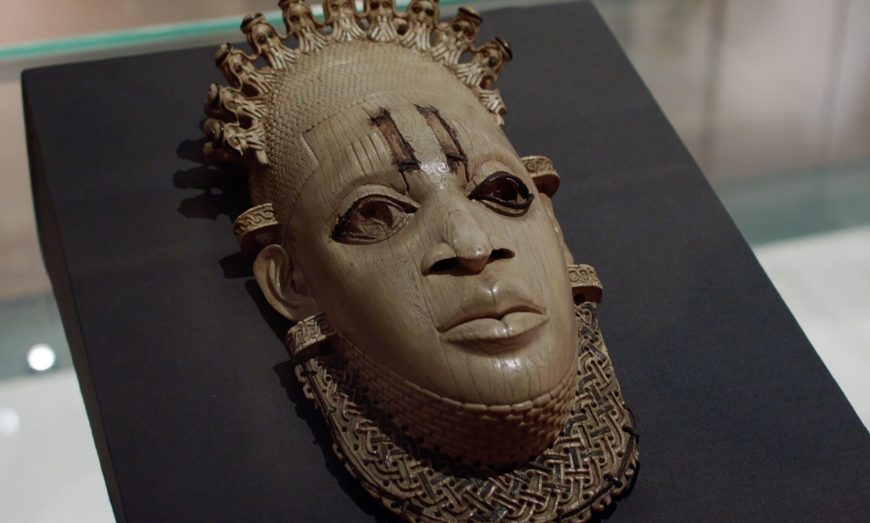

Manilla, Benin Kingdom, Nigeria, 17th century (?), brass, 24 x 26 x 8 cm (Museum für Völkerkunde Wien)

Crossing cultures: a record of trade

Almost every detail in this work speaks to the Benin Kingdom’s mutually beneficial trade with Portugal, which first made contact with Benin in the late 15th century. The Portuguese received items like peppers, cloth, and stone beads from Benin, while Benin received—among other items—the coral that makes up the beads worn by the Oba, and even the brass that makes up this plaque in the form of manillas, or armbands, worn by the Portuguese, which would have been melted down as the raw material for this plaque.

Rosette shape and figure (detail). Equestrian Oba and Attendants, Edo peoples (Benin Kingdom), 1550–1680, Nigeria, Court of Benin, Edo peoples, brass, 49.5 x 41.9 x 11.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The rosette shapes that adorn the background of the plaque were possibly derived from Christian crosses brought by these European traders. Even the horse that the Oba rides was originally introduced to West Africa from across the sea. There is nothing quite like these plaques in all of Africa or Europe from this period, and some scholars speculate that they were created as a way of reconciling traditional African brass sculptural forms with the illustrated books and prints that may have been in the possession of European travelers.

Troubled legacy

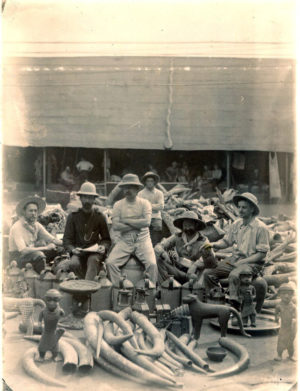

British soldiers sit surrounded by Benin works of art during the British Punitive Expedition of 1897. Robert Allman, 1897, photographic print (The British Museum)

Trade began to decline with Portugal as the Portuguese empire waned in the 18th century. By the 19th century, Britain was seeking to make inroads with Benin as a new trading partner. However, this partnership was much less mutually beneficial and was marked with frequent tension. After increased aggression from both nations, the British launched the Punitive Expedition of 1897, seizing the Oba’s palace, burning down the city around it, killing many, and looting the royal court’s vast stores of art and treasure.

We know that this plaque was one of the artworks looted in the siege because Norman Burrows, a known trafficker in stolen Benin objects, owned it briefly during this time. This act of looting perpetrated by the British was later condemned as a criminal and violent act of British imperialism and colonialism. As such, there are many who believe that objects such as this plaque should be returned to the people of Benin, who remain deeply connected to their history and cultural traditions. However, there are others who feel that these remarkable objects are part of the world’s heritage, and thus should remain in museum collections around the world as testament to this artistically rich culture.

Backstory

A consortium of European museums called the “Benin Dialogue Group,” formed in 2007, has been meeting with representatives from Nigeria to discuss issues around repatriation. Their hope is to establish a system of rotating loans of artworks to Benin City, though the security and guaranteed return of the objects is a point of ongoing discussion, set to continue at a conference in 2018. The consortium includes representatives from the British Museum and Berlin’s Humboldtforum, two of the institutions that hold the largest collections of objects from Benin. Other members of the group include museums in Cambridge, Vienna, Stockholm, Leiden, Leipzig and Dresden, Oxford, Hamburg, and London. Museums in the United States and France, which also hold significant numbers of Benin artworks, have yet to become formally involved, though some, such as the Musée du Quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris, have been approached directly with restitution claims from Nigeria.

The ongoing dialogue between museums and nations from which important objects, like those from Benin, were forcibly removed, highlights the complexities of the current, post-colonial world. Should formerly colonized areas be repaid for the damage inflicted on them by colonial powers? Who is responsible for doing so, and how? Who has the ethical right to the ownership, display, and preservation of these important pieces of cultural heritage? The formation of consortia like the Benin Dialogue Group is a significant first step towards resolving some of these thorny and pressing questions.

Backstory by Dr. Naraelle Hohensee