Repatriation is the return of stolen or looted cultural materials to their countries of origin. Although a belief that looting cultural heritage is wrong and stolen objects should be returned to their rightful owner dates to the Roman Republic (see Cicero’s Verrines) it was not until the 1950s, when the stark truths of colonization and war crimes against humanity began to be exposed, that a broad desire for restitution emerged and laws and treaties to facilitate this increased in number. Repatriation claims are based on law but, more importantly, represent a fervent desire to right a wrong—a kind of restorative justice—which also requires an admission of guilt and capitulation. This is what makes repatriations difficult: nations and institutions seldom concede that they were wrong.

The debate and law

Bronze plaques from the Kingdom of Benin in the British Museum, many removed from Benin City during the Punitive Expedition of 1897 (photo: adunt, CC BY-NC 2.0)

The repatriation of art and cultural objects is a popular topic in the news and there is a familiar list of arguments on either side of the debate. The primary arguments for repatriation, most frequently deployed by countries and peoples who want their objects back, are:

- It is morally correct, and reflects basic property laws, that stolen or looted property should be returned to its rightful owner.

- Cultural objects belong together with the cultures that created them; these objects are a crucial part of contemporary cultural and political identity.

- To not return objects stolen under colonialist regimes is to perpetuate colonialist ideologies that perceived colonized peoples as inherently inferior (and often “primitive” in some way).

- Museums with international collections, often called universal or encyclopedic museums, are located in the Global North: France, England, Germany, the US, places which are expensive to visit and therefore not somewhere most of the world can go to see art. It is precisely a colonial legacy that allowed so many “universal” museums to acquire the range of objects in their collection.

- Even if objects were originally acquired legally, our attitudes about the ownership of cultural property have changed and collections should reflect these contemporary attitudes.

The arguments against repatriation, most frequently deployed by museums and collections which hold objects they don’t want to lose, are:

- If all museums returned objects to their countries of origin, a lot of museums would be nearly empty.

- Source countries do not have adequate facilities or personnel (because of poverty and/or armed conflict) to receive repatriated materials so objects are safer where they are now.

- Universal museums enable a lot of art from a lot of different places to be seen by a lot of people easily. This reflects our modern globalist or cosmopolitan outlook.

- The ancient or historical kingdoms from which many objects originally came no longer exist or are spread across many contemporary national borders, such as those of the ancient Roman empire. Therefore, it’s not clear to where exactly objects should be repatriated.

- Returning cultural objects which were obtained under colonial regimes to their countries of origin does not make up for the destruction of colonialism.

- Most objects in museums and collections, at the time of their acquisition, were legally obtained and therefore have no reason to be repatriated.

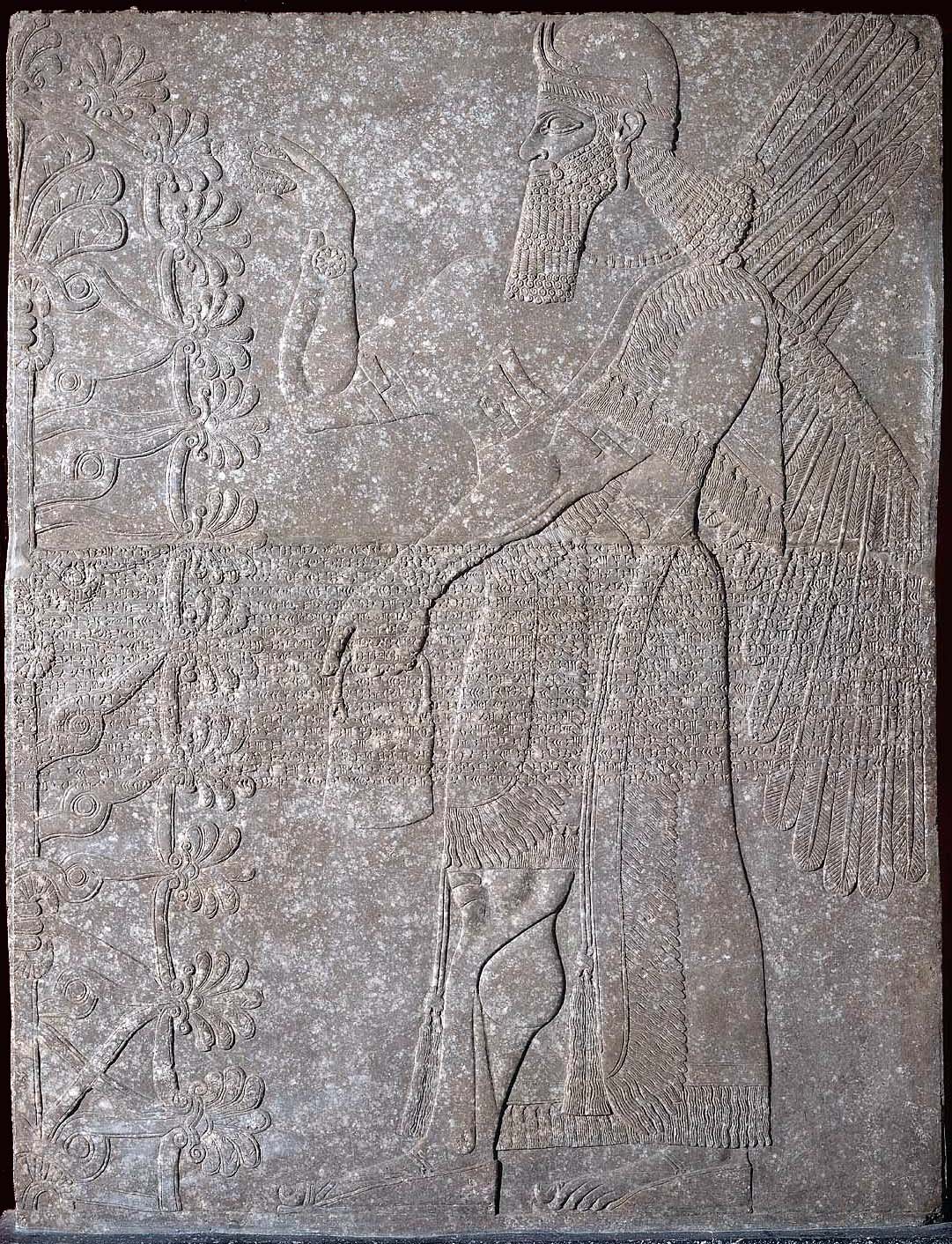

Relief of a protective deity from the Northwest Palace, Nimrud, Iraq, Assyrian, reign of Ashurnasirpal II, 883–859 B.C.E., gypsum, 221.7 x 176.3 cm (87 5/16 x 69 7/16 inches) excavated by Sir Henry Layard by the 1850s (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

The debate over repatriation engages powerful and personal sentiments of morality, nationhood, and identity, and few people can talk about it without raising their voice. Regardless of this passion, however, the issue, ultimately, is a legal one and the international legal frameworks developed in the 20th century are what bring about repatriations. The first, which recognized the damage of warfare to property, was the 1907 Hague Convention, which forbade plundering of any kind during armed conflict, although it did not deal specifically with cultural property. The 1954 Hague Convention, however, in the wake of the widespread destruction of art during the Second World War, sought to expressly protect cultural property during armed conflict. The 1970 UNESCO Convention allowed for stolen objects to be seized if there was proof of ownership, followed by the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects, which calls for the return of illegally excavated and exported cultural property. Without these conventions and treaties, there would be no legal obligation for the return of anything.

Claims of repatriations

The Koh-i-Noor in the front cross of Queen Mary’s Crown (Royal Collection Trust)

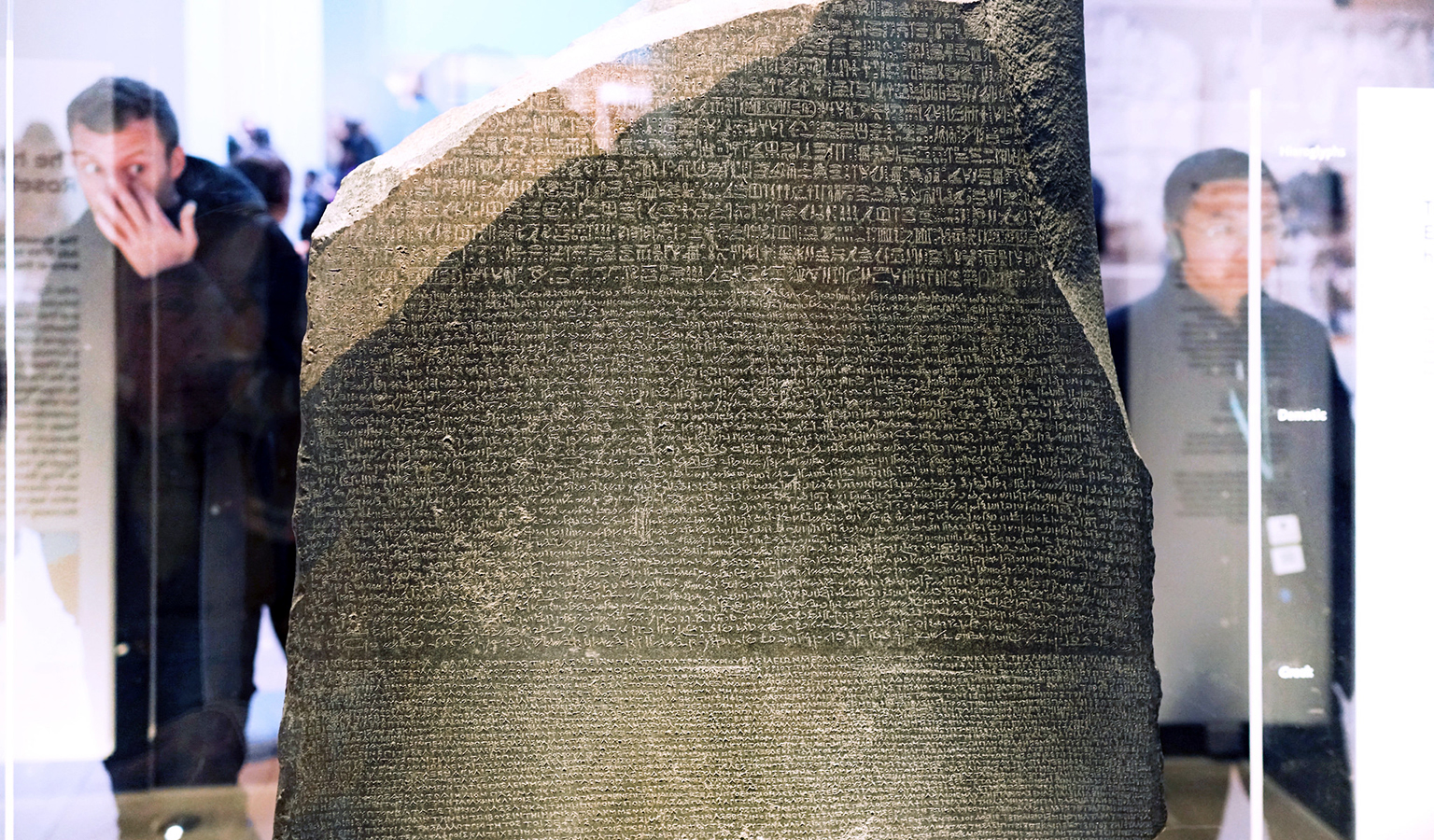

The vast majority of repatriation cases derive from colonial or imperial subjugation. Throughout history, across the globe, powerful nations and empires have taken valuable objects, including cultural property, from those they have conquered and colonized. These objects of beauty and esteem number in the many millions and most will likely be lost to their former owners forever. However, the theft of a few especially valuable and/or important objects have proven unforgettable and the subject of frequent repatriation requests. Examples are, for instance: the Koh-i-noor diamond, seized by the British East India company in 1849 and currently part of the British crown jewels; the Benin Bronzes, looted from the capital of Benin (in modern Nigeria) by British soldiers in 1897 and now spread across several museums in Europe and America; the Rosetta Stone, seized by British troops from the French army in Egypt in 1801 and today one of the most popular exhibits in the British Museum in London. The Parthenon Sculptures are another example.

Visitors view the Rosetta Stone in the British Museum (photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Repatriation cases such as these have been approached, by and large, on a case-by-case basis, between the nations seeking return and the nations (and sometimes specific institutions), which hold these objects. More recently, however, as pressure for repatriations has increased, some former colonial powers are taking stock of their collections and moving towards large-scale repatriations. For instance, in 2017 France commissioned a report which recommended the repatriation of objects in French museums acquired during France’s colonial occupation of parts of western Africa.

National Museum of World Cultures (Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam)

In 2019, the German government passed a resolution to lay the groundwork to establish conditions for the repatriation of human remains and objects from German public collections derived from colonial rule. In 2019, The Netherlands’ National Museum of World Cultures pledged to proactively return all artifacts within its collection identified as stolen during the colonial era. These efforts, importantly, include sharing catalogues of holdings, a gesture of transparency which will greatly facilitate claims. However, as many point out, the stated intentions for large-scale repatriations are proving very, very slow to come to fruition and, moreover, several important museums (many in the United Kingdom) are conspicuous in their absence from the conversation.

Colonialist desires to collect beautiful objects from far flung, exotic sources are still with us and because of this, wealthy individuals and institutions continue to collect cultural objects, ancient and contemporary. To meet this demand, modern looters (people who illegally dig up and steal cultural property) feed an underground market of antiquities and ethnographic objects. Often this looting is in conjunction with war or armed political conflict.

Iraqi Col. Ali Sabah, commander of the Basra Emergency Battalion, displays ancient artifacts Iraqi Security Forces discovered Dec. 16, 2008, during two raids in northern Basra (photo: U.S. Army by Multi-National Division South East PAO, public domain)

Repatriation claims for objects involved in this illegal trade of cultural property are especially difficult as proof must be established of the illicit extraction of the objects and thieves seldom document their work, especially in war zones. Moreover, these types of repatriation requests symbolize fresh colonial wounds, illustrating that the collection practices of the wealthy and powerful continue and less powerful nations and people are still vulnerable.

The good news is that successful repatriations of recent looting have occurred and those who purchase from the illicit trade are increasingly discouraged from doing so. For instance, in 2011, the Museum of Fine Arts Boston returned a Roman sculpture of Herakles to Turkey from which it had been stolen. In 2018 The National Gallery of Australia returned to India a bronze statue of the god Shiva which had been looted from a Hindu temple in Tamil Nadu. In 2020 The Museum of the Bible in Washington, D.C. returned nearly 11,500 looted objects to Iraq and Egypt, including approximately 5,000 papyri fragments and 6,500 clay tablets.

Another type of repatriation request is for the return of cultural objects and burial remains stolen from Indigenous populations by European invaders, largely in North and South America, Australia, Oceania, and New Zealand. What distinguishes these claims is the enduring living memory, among contemporary tribal communities, of specific objects and sites which were looted and desecrated and the acute spiritual need for their return and restoration. Indeed, these fragments of living culture can only be fully understood, properly used, and rightly treasured by their native owners.

In an attempt to address these sorts of repatriation requests, two legislated responses, the Native American Graves and Protection Repatriation Act (in the US,) and the Indigenous Repatriation Program (in Australia) were enacted. Through these two programs, legal frameworks for repatriation were established and hundreds of thousands of objects and human remains have been returned to Indigenous communities where they again work as powerful actors in the creation of spiritual, community and personal meaning. A famous example is the return of The Ancient One (also called Kennewick Man) after five Pacific Northwest tribes argued that the human remains were an ancestor. Still, the successful repatriation occurred only after genetic testing done by Danish scientists proved the Indigenous peoples’ claim, highlighting the ongoing colonialist legacies affecting cultural repatriation.

Moai Hoa Hakananai’a, taken from Orongo, Easter Island (Rapa Nui) in November 1868 by the crew of the British ship HMS Topaze and now in the British Museum (photo: Markus Lütkemeyer, CC BY 2.0)

The era of repatriations has finally come. The work is slow and uneven and there are countless objects yet to return home, but repatriations are now occurring at a rate never before seen. What examples such as the Euphronios krater show us about repatriation is that objects come back changed. Not only physically but, because of the way they have been used (often ideologically) in their meanings as well — and, they cannot be changed back. Even if they are exhibited in quiet and historically proscribed ways (as in the case of the Euphronios krater), their life experience has made them bigger, louder, emotional, and more political.

Duveen Room, British Museum, Phidias(?), Parthenon Frieze, c. 438-32 B.C.E., pentelic marble (420 linear feet of the 525 that complete the frieze are in the British Museum, photo: Dr. Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

When, for instance, the Parthenon marbles return to Athens they will never again only be the sculptural decorations of Athena’s 5th century B.C.E. temple. They have become so much more to Greeks, the English, generations of artists, historians, protectors of heritage, politicians, art law lawyers, and millions of visitors to the Acropolis and the British Museum. Through their dramatic biographies, we very much want to connect with, visit and understand repatriated objects and because of this they will not slip into obscurity in local museums, as is sometimes feared. The great power, the searing meaning that repatriated objects communicate, is that lost things can come home, that a wrong can be righted, and that we can all take part in that celebration and moral victory.