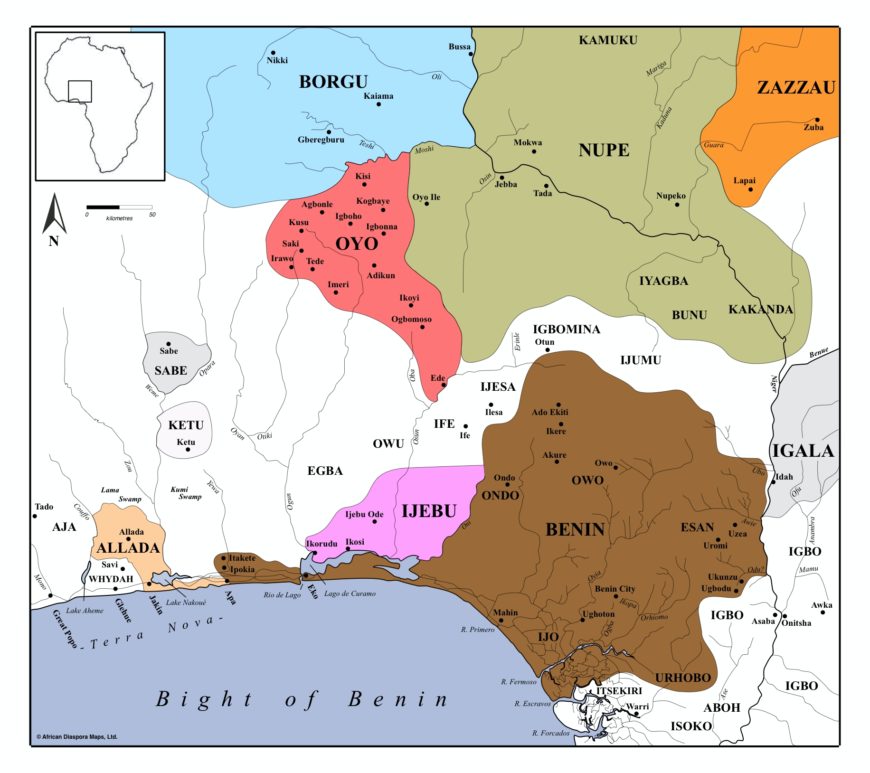

States of the Bight of Benin Interior c. 1580, courtesy of Henry B. Lovejoy, African Diaspora Maps Ltd., (CC BY 4.0)

In the age of social media, nearly everyone can present an idealized version of their real lives to the world. In the past, however, only the wealthiest and most powerful could afford to shape their image for the public. During the sixteenth century, the kings of Benin (in present-day Nigeria), reigned over nearly two million subjects and commanded a feared military force, but they also faced internal political problems that threatened the throne.

Politics, power, and art

The Kingdom of Benin was founded around the year 900, but it reached the height of its power in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries as a result of the conquests of new territories by two kings —Oba Ewuare and his son Oba Ozolua (Oba means “king”).

The Obas of Benin amassed great wealth by controlling trade routes reaching from the river Niger in the East to the western border with the kingdom of Dahomey. Taxes on pepper, ivory, and enslaved persons, and annual tribute payments from conquered lands in their expanding empire, also increased the wealth of the Kingdom.

Royal art from this period (and from a slightly later time of renewed wealth and power in the eighteenth century), was designed to broadcast and strengthen dynastic power. Benin court art celebrates the prestige of the monarchy to outsiders (like traders and ambassadors), as well as to courtiers who might try to wrest power from the king.

In the early sixteenth century, Oba Esigie successfully consolidated Benin’s power over conquered territories. He took the throne after a civil war with his older brother and soon after defended Benin City from an attack from a neighboring kingdom (Idah). His commissions were designed to address the turmoil of his early reign. Esigie was a brilliant politician, and he commissioned great works of art and new festivals to assert the legitimacy of his reign.

The festival of Ugie Oro

Esigie instituted the festival of Ugie Oro, where high-ranking courtiers process around Benin City striking bronze staffs with a bird on top. The festival refers to the Idah war, when leading courtiers refused to support Esigie in his defense of the city. A bird in a tree en route to the battle prophesied that Esigie and his troops would be defeated. Esigie shot the bird and carried it as his battle standard. When he won the war against the Idah, he instituted the festival to point out that the advice of the courtiers—and the bird—had been nothing more than the empty noise produced by clanging the bronze staffs, pointing out that courtiers’ should defer to the wisdom of the king.

Artist Unidentified, Staff showing a bird of prophesy, 19th century, Copper alloy (Robert Owen Lehman Collection, Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

In the plaques he commissioned to ornament his audience hall, Esigie surrounded himself with images of courtiers in processions, including the festival of Ugie Oro, or engaging in other acts of service and praise—reminding them to honor and obey his authority. Today, artworks from the period of Esigie’s reign are among the most celebrated in African art history, combining fascinating narratives on the majesty of the kingdom, luxurious materials, and fine workmanship.

Royal patronage in the 18th and 19th centuries

Throne stool of Oba Eresoyen, 1735-50, Kingdom of Benin, Nigeria, brass, 40 x 40.5 cm (Ethnological Museum of the National Museums in Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz)

Changes in Benin art are tightly intertwined with the changing fortunes of the kingdom, because the Oba was historically the primary patron for all artwork in bronze and ivory. In the beginning of the eighteenth century, Benin recovered from a series of succession struggles and wars that weakened the court and devastated its finances. Oba Akenzua I and his successor, Oba Eresoyen, strengthened the king’s role and instituted new traditions and art forms to signal their regained power.

Akenzua and Eresoyen ushered in a period of renewed wealth and political power for the kingdom that continued into the 19th century. Akenzua and Eresoyen compared themselves to Ozolua and Esigie, starting the tradition of viewing Ozolua and Esigie as two of the most important kings in Benin history.

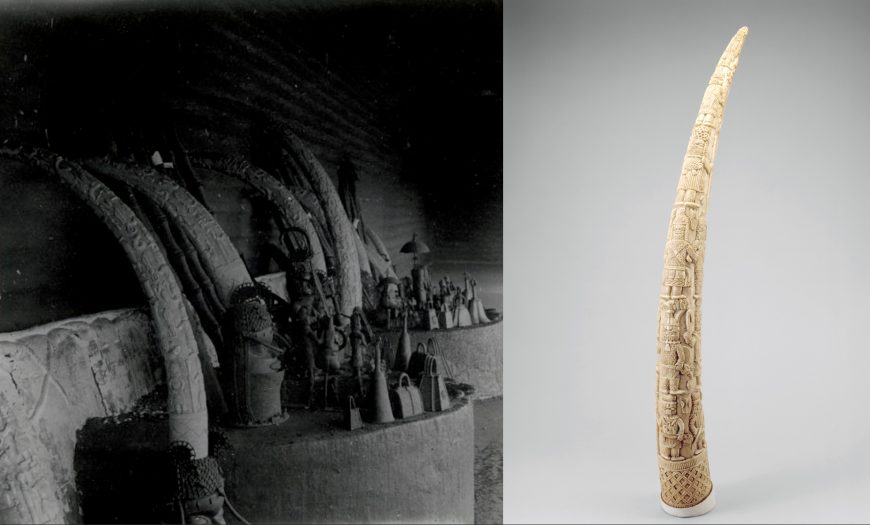

Oba Eresoyen was a major patron of the bronze-casting guild, and commissioned an elaborate copy of a bronze state stool owned by Oba Esigie—metaphorically connecting the two reigns. Eresoyen is also known as a patron of the ivory guild, and may have introduced the intricately carved tusk for memorial altars that first appear in the eighteenth century.

On memorial altars, ten to sixty tusks were displayed on top of brass commemorative heads. The tusk held in the Berlin Ethnographic Museum, is one of the oldest known. We see an Oba, his arms supported by attendants, placed in the center of the tusk, the most visible position. Surrounding this central triad are figures relating to the dynasty of great Obas—including two Portuguese men on horseback that refer to the reigns of Ozolua and Esigie—and motifs representing leading courtiers and priests serving the king.

Benin ancestral altars (left), photographed in 1936 (Etnografiska museet, Stockholm) and an altar tusk (right) 1888 – 97, Kingdom of Benin, Nigeria, ivory, 111.8 x 31.5 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

The artists

The Igun Eronmwon (brass-caster’s guild), and the Igbesanmwan (ivory and wood carvers’ guild), are responsible for all the art made for the Oba. Until the 20th century, royal artists were not allowed to make pieces for other clients without special permission. Membership in the royal artists’ guilds is hereditary—even today. The head of each guild inherits his position from his father. He is responsible for receiving commissions from the king, overseeing the design of the work, and assigning parts of the project to different artists. For this reason, nearly all historical Benin art is made in a workshop style, with individual artists contributing pieces of the whole.

While the Igun Eronmwon and Igbesanmwan guilds are separate, they often make artworks that are displayed together. Commemorative heads made for the memorial altar of a king (see ancestral altars above), for example, combine a cast-bronze head with a carved ivory tusk rising from the top, just as an ivory leopard may be finished with inlaid bronze spots.

Controversy

Pair of leopards, 19th century, Court of Benin, Nigeria, ivory with metal inlay, 48.0 x 80.0 x 13.0 cm (Royal Collection Trust, © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2017)

Like other artworks taken from their place of origin by colonial occupiers, artworks from Benin are part of a public conversation on cultural patrimony and the ethics of collecting. The provenance (ownership history), of Benin artworks in Europe and America usually includes a moment in 1897 when Benin City was invaded by British soldiers and a part of the royal treasury was claimed by the British state as spoils of war. In the following years, other artworks were taken from Benin by individual soldiers, or pillaged from the palace and sold.

Today, the palace in Benin City and the Nigerian government both claim ownership of Benin art held in foreign collections. Museums and private owners have provided a spectrum of responses. In 2014, British citizen Mark Walker returned two Benin artworks he inherited from his grandfather, a soldier in the 1897 invasion, to reigning Oba Erediauwa, because he felt that the Oba was the only rightful owner. The Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) Museum is working to determine how to return a commemorative head to Nigeria, given the competing claims of the palace and the government.

A coalition of European museums that hold the largest collections of Benin art have been meeting with representatives of the palace and the Nigerian government since 2007, and at present plan to collaborate by sharing their collections through loans to a new Nigerian museum built on palace grounds. The public conversation on Benin art weighs the competing ownership claims of the palace and the government, the ethical obligation to respect communities’ rights regarding their cultural patrimony, and the belief that museum collections should present world art to foster cross-cultural understanding.