Jacques-Louis David, Portrait d’Antoine Laurent et Marie Anne Lavoisier, 1788, oil on canvas, 259.7 x 194.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

The room is quiet, except for the sound of Antoine Lavoisier’s feather quill scratching on parchment. The chemist sits at a velvet-draped bureau plât laden with the tools of his work: a volumetric flask, beam balance, barometer, and thermometer, as well as a large green and gilt box. He leans forward slightly, resting his elbow on the thick manuscript of his soon-to-be published book, the Traité Élémentaire De Chimie (Elements of Chemistry). Although surrounded by the materials of his beloved work, Mr. Lavoisier is focused on someone else: his wife, Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze Lavoisier. She stands behind him with her left arm resting casually on his right shoulder. Her right hand pauses on the desk next to his pen. Although Antoine Lavoisier looks directly at her, Marie-Anne looks out of the canvas and directly at the viewer with a slight smile on her face.

The Lavoisiers (detail), Jacques-Louis David, Portrait d’Antoine Laurent et Marie Anne Lavoisier, 1788, oil on canvas, 259.7 x 194.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

Jacques-Louis David’s Portrait of the Lavoisiers depicts a husband and wife in their Parisian home. In 18th-century France, domestic portraits of married couples were fashionable among the middle- and upper-classes. They were often composed to reflect a broader societal interest in marital and familial love, which was championed by Enlightenment philosophers. David’s painting embraces these ideas while also showing a new kind of marriage for the time: one built on the spouses’ mutual interests and collaborative pursuits. Carefully observing the details David included in this painting (and the recent discovery of ones that were purposely omitted) reveals unexpected insights about who the Lavoisiers were: an intellectual power couple who would experience profound tragedy shortly after this commission.

Scientific glassware (detail), Jacques-Louis David, Portrait d’Antoine Laurent et Marie Anne Lavoisier, 1788, oil on canvas, 259.7 x 194.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

A scientific power couple

The Lavoisiers first met Jacques-Louis David through their mutual connections to the science and art worlds of 1780s Paris. Jacques-Louis David and Antoine Lavoisier had both attended school at the Collège Mazarin, and the artist socialized with several prominent members of the Royal Academy of Sciences. In both science and art, precision is a core standard of practice, and David’s painting expresses this both visually and stylistically. The gleaming glass instruments on Lavoisier’s desk are rendered with exacting clarity. Their reflections and curved surfaces encourage the viewer to lean in and observe closely. Marie-Anne’s white gown and wisps of powdered hair indicate David’s disciplined attention to how light and texture respond to different materials. The focused realism of the painting is an artistic counterpart to the Lavoisiers’ scientific rigor.

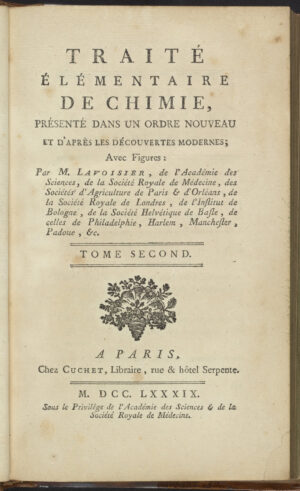

At the time David painted the portrait, Antoine was preparing to publish Elements of Chemistry, a book that redefined chemistry as a rigorous and empirical science. The crisp, white pages of the manuscript hang over the edge of the desk, and both Antoine’s and Marie-Anne’s hands are positioned next to them, indicating their shared contributions to the book. David’s portrait emphasizes the seriousness of Antoine Lavoisier’s career and discoveries while also including details that highlight Marie-Anne’s indispensable contributions to her husband’s work.

Antoine Lavoisier, Traité Élémentaire De Chimie (Elements of Chemistry), with engravings by Marie-Anne Lavoisier (Paris: Cuchet, 1789) (Science History Institute, Philadelphia)

When they sat for this portrait, Antoine and Marie-Anne had been married for seventeen years. Marie-Anne had attended a convent school which focused instruction on literacy, manners, and moral or religious education, but her knowledge of English, chemistry, and art suggests that she was also taught more rigorous subjects. She met Antoine Lavoisier through her father, and the two married when she was thirteen and he was twenty-eight. While historical accounts describe their marriage as a mutually-welcome partnership, no first-hand written accounts from Marie-Anne’s perspective have been found. She translated English publications for his team and also illustrated his chemical manuscripts.

Marie-Anne Lavoisier, A man seated in a barrel with his head under a glass canopy; he breathes and his pulse is taken; Lavoisier dictates to his wife who is writing a report, c. 1790, pen with brown ink wash, 24.2 x 32.4 cm (Wellcome Collection, London)

Her drawings embody the Enlightenment ideal of disciplined observation and precision, and they reflect the scientific demand for accuracy in the visual documentation of experiments. Several are set in Lavoisier’s somber and serious laboratory. As he and his team are depicted testing the limits of human respiration, Madame Lavoisier is also present with her quill and parchment, observing the experiment and recording observations as they occur. She is sometimes depicted in conversation with them, and in others, she’s absorbed in her work, leaning over the desk to sketch the procedures. Marie-Anne’s illustrations not only lend validity to her husband’s experiments, but they also affirm her own role as a trained observer and visual documentarian. In David’s painting of the couple, a large artist’s portfolio is propped on a chair in the back left corner of the room, with Marie-Anne’s black shawl draped over the chair’s arm next to it. This subtle detail suggests that Madame Lavoisier had just put down her own belongings to join her husband at his desk. It implies that Marie-Anne’s art-making was not just for support or assistance, but a serious endeavor of her own.

A femme-artiste in David’s studio

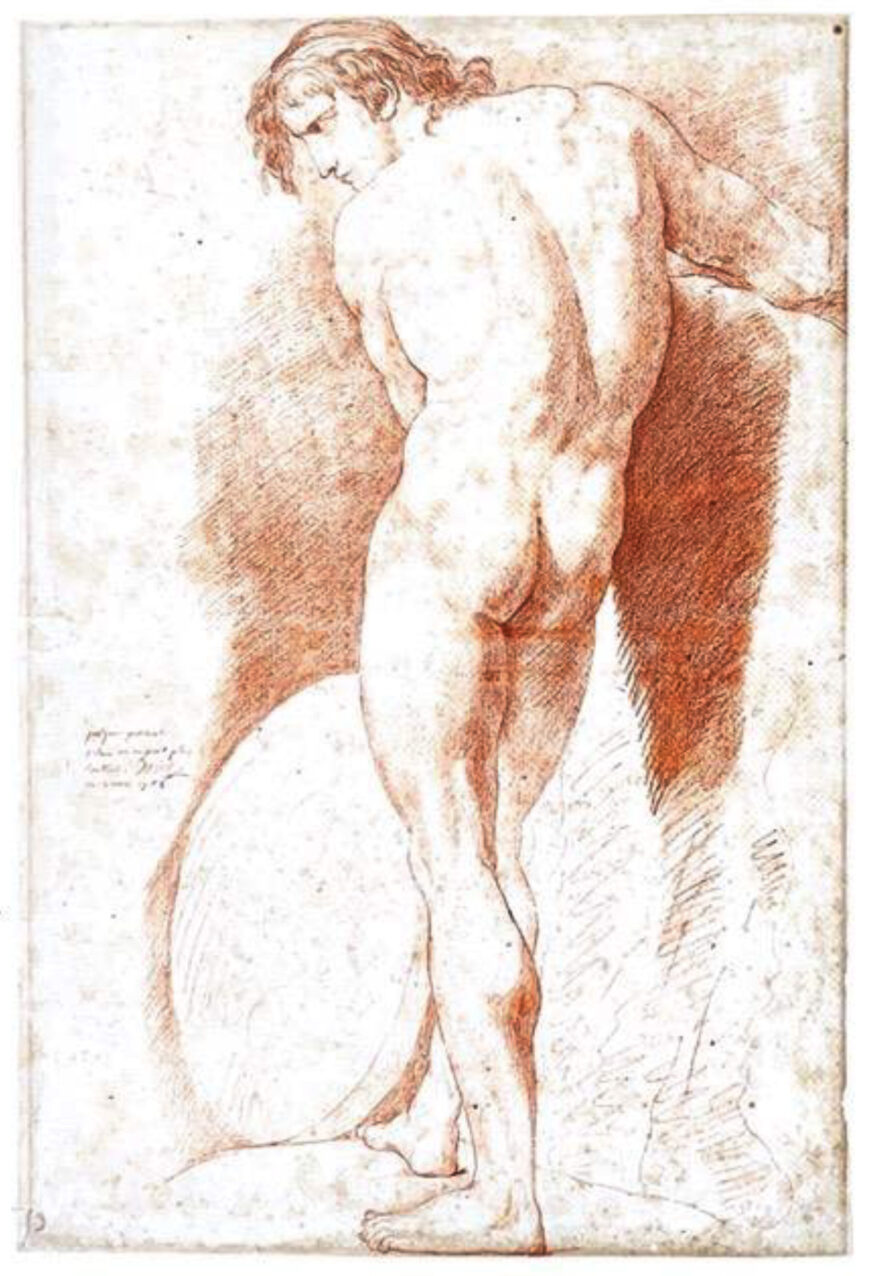

In 18th-century France, women artists seeking to be taken seriously faced extraordinary challenges. Admission to “official” institutions, like the The Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, was limited to only four women at one time—and even then, female Academicians were barred from drawing the nude model based on social and moral propriety. Despite these barriers, Marie-Anne began formal study with Jacques-Louis David in 1785, just a few years before he painted her portrait. In David’s painting of the Lavoisiers, Marie-Anne’s white muslin dress, lace collar, and blue sash indicate that she participated in the latest fashions of her time. Objects like her nécessaire, a compact case for pens, ink, and drawing tools, show her sustained dedication to art-making in any environment. Although not visible in the painting, Marie-Anne concealed the case in a leather binding labeled History of Theater, which stands as a reminder of the discreet nature of her creative practice.

Marie-Anne Lavoisier, Drawing of a Nude, 1786, red chalk on paper, 60.8 x 41.3 cm (Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris)

The large artist’s portfolio in the background of the portrait is a telling acknowledgment that Marie-Anne’s artistic work was integral to her life. For example, a red charcoal study of the male nude demonstrates that Madame Lavoisier took advantage of opportunities afforded to her under David’s tutelage and that she advanced in her studies of art despite the limits imposed on her. While Antoine gazes lovingly up at her, Marie-Anne’s eyes are directed toward her teacher. This detail subtly elevates her position from supportive spouse to active participant in the intellectual and artistic pursuits of her time. The portrait firmly situated the Lavoisiers within the Enlightenment’s views on the transformative power of knowledge, skill, and partnership.

Portrait of an enlightened family

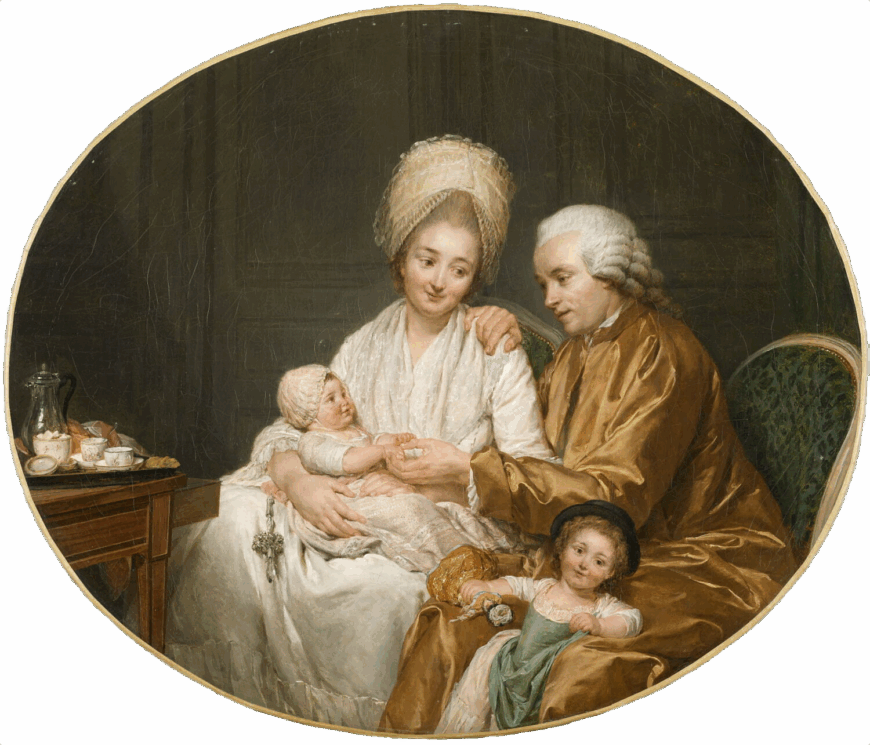

In the 18th century, Enlightenment philosophers highlighted the family as the cornerstone of a healthy society and emphasized that mutual admiration between spouses were increasingly important ideals to be emulated. Portraits visually expressed these values. Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié’s portrait of Étienne Marc Quatremère and his family, painted in 1780, depicts the scholar, his wife, and two children as the ideal Enlightenment family. The oval canvas pictures the Quatremères enjoying a cozy, intimate breakfast. Étienne Marc wears a silk dressing gown, and his wife wears a white muslin and lace dress, shawl, and cap. At a nearby table is a gleaming silver coffee pot with a white and rose sugar bowl sitting open to reveal thick, white cubes used to sweeten their drinks. These details are evidence of France’s deep involvement in colonial trade networks during the 18th century, as well as the Quatremères’ ability to afford the luxuries those networks supplied.

Nicolas-Bernard Lépicié, Portrait of Quatremère and His Family, 1780, oil on canvas, 53 x 62 cm (Musée du Louvre, Paris)

The pair appear as a unified whole, with Madame Quatremère at the center of domestic life in Lépicié’s painting. Instead of a confidante, though, she’s a doting complement to her husband. Madame Quatremère looks down and toward her eldest child, who is leaning against Étienne Marc’s legs. He leans in to clasp the hand of their infant, and his right arm rests gently on his wife’s shoulders. The scene shows an easy, loving image of a nuclear family where everyone plays their “natural” roles.

The Lavoisiers (detail), Jacques-Louis David, Portrait d’Antoine Laurent et Marie Anne Lavoisier, 1788, oil on canvas, 259.7 x 194.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

In the Portrait of the Lavoisiers, Marie-Anne leans affectionately on Antoine’s shoulder, and his reciprocal gaze affirms a convention of Enlightenment family portraits where close physical arrangement and interlaced forms conveyed familial unity. Yet David’s composition shows a different kind of collaboration, reinforced by the couple’s intellectual tools: Antoine’s desk, overflowing with the apparatus of chemistry, and Marie-Anne’s nearby artist’s portfolio. This intertwining of science and art embodies Enlightenment ideals of progress through reason and shared purpose. Rather than a portrait of a patriarch and his spouse, the painting is a visual argument for the productive power of a partnership.

Charles de Wailly, Projet rétrospectif pour la présentation des ouvrages de l’Académie au Salon carré du Louvre en 1789, 1789, pencil and sanguine on paper, 33.4 x 37.4 cm (Musée Carnavalet, Paris)

A revolutionary salon

The Salon (the official art exhibition of the Academy of Fine Arts) of 1789 opened on August 25 to a Paris that had already been transformed. Six weeks earlier, the storming of the Bastille had ushered in the French Revolution, and the Louvre’s galleries became charged spaces where public opinion collided with art and politics. David had intended to exhibit the Lavoisier portrait, but Antoine and Marie-Anne never made it to the Salon walls. By August, rumors had circulated that Antoine Lavoisier had conspired to thwart Revolutionary efforts. While this accusation was born of political mistrust rather than fact, the Academy encouraged the portrait’s withdrawal to avoid associations with the volatile politics of the moment.

Original and X-ray image showing David’s overpainted changes, Jacques-Louis David, Portrait d’Antoine Laurent et Marie Anne Lavoisier, 1788, oil on canvas, 259.7 x 194.6 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

In 2021, conservators at the Metropolitan Museum of Art published the findings of their x-ray analysis of the Lavoisier portrait, which ultimately revealed that David had been concerned with the public perception of the painting. Underlayers of the painting show that the artist made several alterations to minimize the Lavoisiers’ aristocratic ties and extravagant lifestyle. In the original version, more items filled the scene: a large bookcase filled with enormous tomes stood against the back wall, a globe sat on Antoine’s desk, and Madame Lavoisier was dressed in a tall chapeau à la Tarare. By reworking the composition to recast the couple as progressive thinkers rather than privileged elites, David might have been trying to appeal to the public by visualizing them as an embodiment of the “natural” social order, where mutual love forms the basis of a just society and intellectual inquiry leads to human betterment.

Afterlives

The 1789 Revolution that reshaped French society would ultimately set David and the Lavoisiers along different paths. Antoine’s scientific achievements could not shield him from political retribution. Both Antoine and Marie-Anne were arrested during the Reign of Terror, and in May 1794, Antoine was tried and convicted of financial crimes. He was guillotined on the same day as Marie-Anne’s father, Jacques Alexis Paulze.

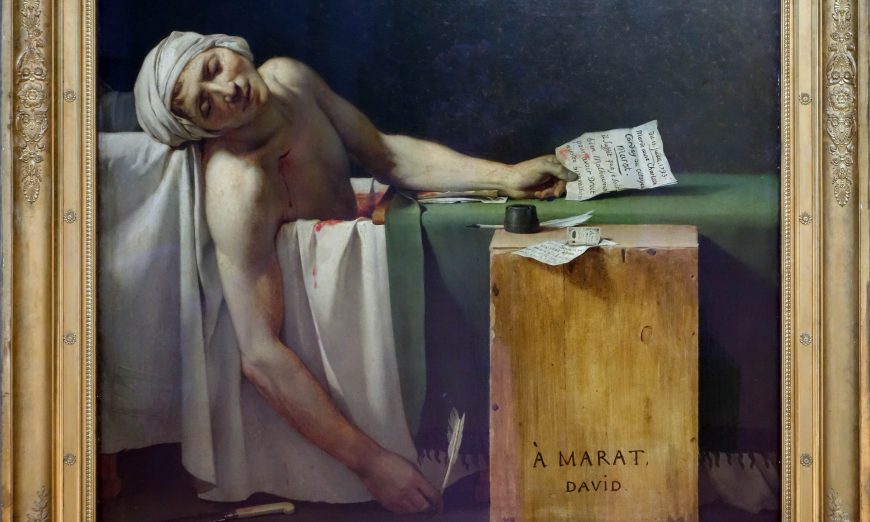

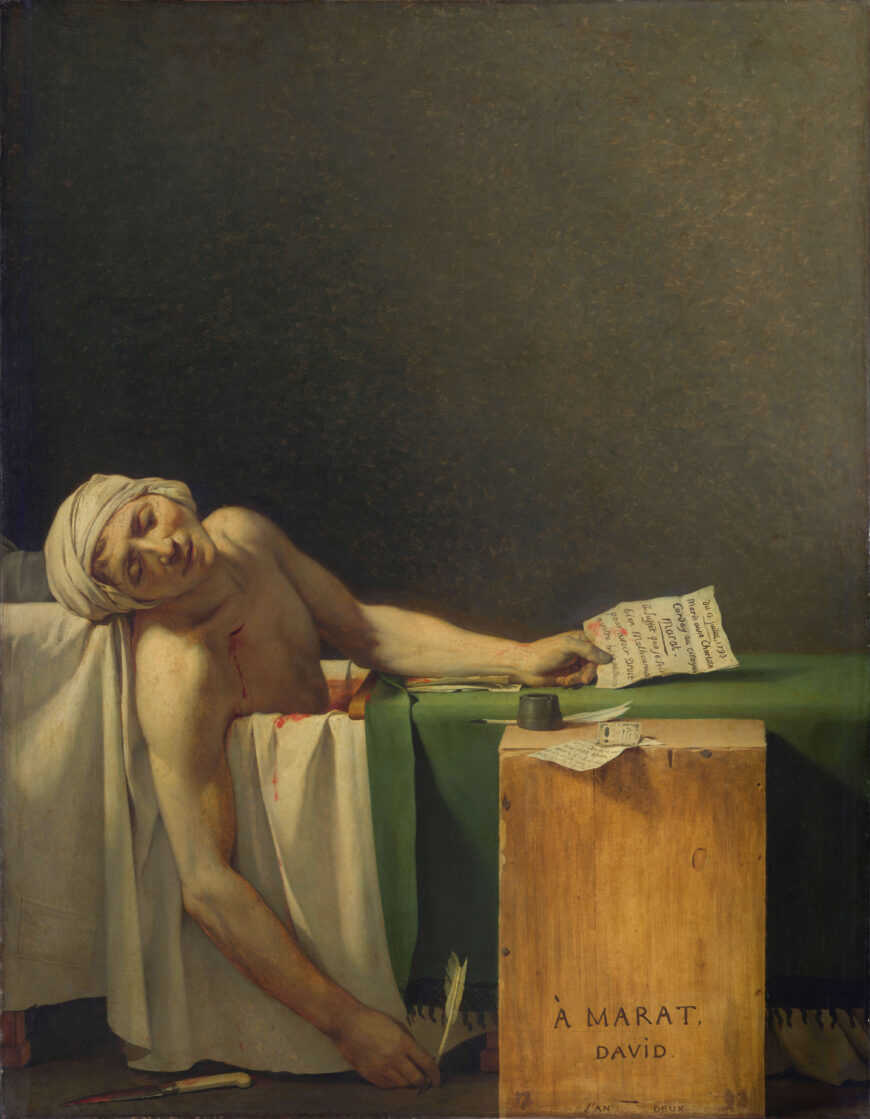

Jacques-Louis David, Death of Marat, 1793, oil on canvas, 165 x 128 cm (Royal Museum of Fine Arts, Brussels)

David, meanwhile, adapted his art to the Revolution’s shifting tides. Throughout the 1790s, he produced portraits and history paintings that celebrated revolutionary martyrs and civic unity before becoming Napoleon’s court artist during the First Empire. The Bourbon Restoration abruptly put an end to David’s working life in Paris. In 1816, he was exiled from France and moved to Brussels. He died in 1825.

Marie-Anne spent sixty-five days in prison before she was released after Antoine’s death by guillotine. In the years after, she worked to preserve Antoine’s legacy by retrieving his confiscated books and ensuring that his ideas remained in print. She lived to the age of seventy-eight, and to the end she was a steadfast custodian of the Lavoisier name and its reputation in the scientific world.

Although David and the Lavoisiers never reunited, the 1788 painting preserves a time when three individuals connected over a mutual interest in science and art. It also shows how a moment could be edited, painted over, and then ultimately transformed by the French Revolution and its aftermath. The Portrait of the Lavoisiers remains a record of a partnership that was carefully refashioned to meet the broader context of its moment.