Agostino Brunias, Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape, c. 1770–96, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 66.4 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

A group of thirteen people, of varying ages and social standing, walk through an idealized landscape accompanied by three comically miniature dogs. This scene, Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape, by the Italian painter Agostino Brunias in the late 18th century is set in the Lesser Antilles. The artist lived and worked in Dominica and St. Vincent after first arriving in the Caribbean sometime in the second half of the 1760s and this scene is likely set on one of these two islands.

The representation of new colonial subjects

Three Black women toward the left side of the composition (detail), Agostino Brunias, Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape, c. 1770–96, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 66.4 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Three women of color stand in the center of the group. Each is finely dressed in tall headwraps topped with wide-brimmed hats. They may represent members of a family, two young women and their mother in the yellow petticoat. They are clearly the protagonists of this painting, especially the woman dressed all in white who points to a light-skinned boy in white and gold, likely her son. Their elegant dresses with laced bodices, the fichus over their shoulders, and hats set them apart visually from the rest of the group.

We also see three Black women toward the left side of the composition. Two of them wear striped short gowns and white headscarves without hats. They wear some jewelry; the Black woman in the green skirt is adorned with a necklace and bracelet in coral. It is possible that these women are domestic servants who work for the more elaborately dressed women in the foreground. The status of the third Black woman in the background as a domestic servant, perhaps an enslaved one, is clearer in the simplicity of her clothes. She is dressed in a modest white skirt and short gown, with a simple scarf tied under her chin to cover her head. She looks after a light-skinned child, carried on her shoulder and likely the progeny of one of the women at the front of the group.

Agostino Brunias, Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape (detail), c. 1770–96, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 66.4 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Three adult Black men accompany the women. They stand behind them and appear to be dressed in uniform (with white vests, breeches paired with stockings, hats, and blue and gold jackets). This is the same attire worn by the two Black boys on the right of the composition. The boys do not wear stockings or shoes. These men and boys appear to also be servants, and may be enslaved. A stark contrast is made between the barefooted boys and the finely dressed light-skinned boy who accompanies them and wears shoes as stockings.

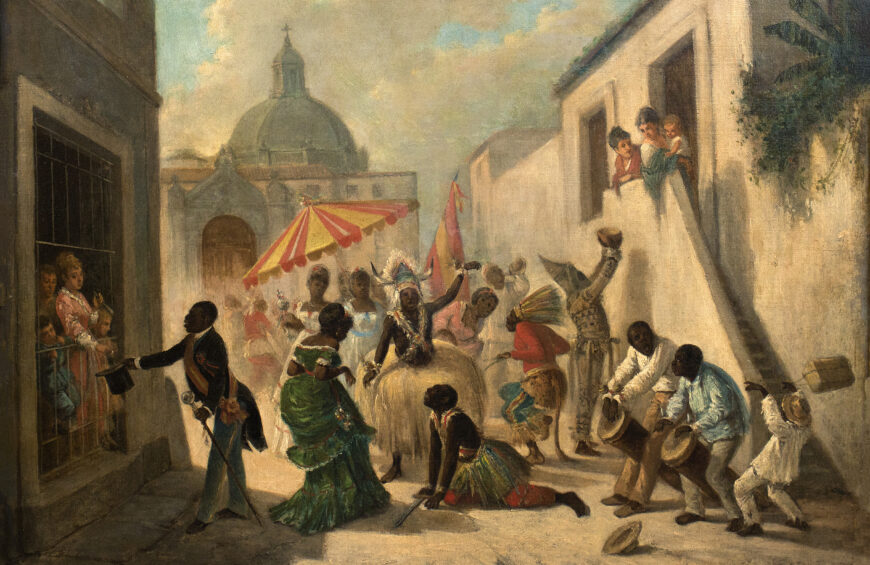

This painting encapsulates some of the racial dynamics in the 18th-century Caribbean, particularly found in French and Spanish colonies where notions of racial mixing and mobility were considerably more fluid than in British colonial society. In French and Spanish Caribbean colonies free Black people were, in some circumstances, able to improve their socioeconomic standing. This included owning businesses or plantations, having servants and enslaved individuals, marrying Europeans or white Creoles.

Great Britain had come into possession of some French territories (including Tobago and the Grenadines), after the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, which finalized the Seven Years War between Britain and France and stipulated that the French cede several of their American territories. In 1764, a commission was created to oversee the sale of these lands in public auction. Sir William Young was appointed as its president and relocated to the Caribbean to travel and supervise the proceedings. Brunias, the artist of this painting, was part of his entourage, and accompanied Young as he traveled through the island, sketching much of what they saw there.

Left: Agostino Brunias, Linen Market, Dominica, c. 1780, oil on canvas, 49.8 × 68.6 cm (Yale Center for British Art); right: Agostino Brunias, A West Indian Flower Girl and Two other Free Women of Color, c. 1769, oil on canvas, 31.8 x 24.8 cm (Yale Center for British Art)

The people of the Lesser Antilles became Brunias’s preferred subject, and Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape is representative of his work in the Caribbean. Perhaps as commissions or as a byproduct of his initial observations, the artist also produced genre scenes (images of everyday life) and paintings where he focused on particular groups. We see this in two of his other paintings, Linen Market, Dominica and A West Indian Flower Girl and Two other Free Women of Color. Here, he uses scenes set in markets and town streets to represent the interactions of social classes as opposed to the ordered hierarchy we see in Free Women of Color with Their Children.

Agostino Brunias, Free West Indian Dominicans, c. 1770, oil on canvas, 31.8 x 24.8 cm (Yale Center for British Art)

In all three of these compositions, Black and dark-skinned figures tend to be represented as servants, enslaved individuals, or vendors. Those read as of mixed ancestry are often represented likewise. In contrast white or light-skinned figures are usually represented as more affluent. This is not always the case, as we can see in Free West Indian Dominicans, where two finely dressed Black women and a Black man are represented in casual conversation. Brunias’s images serve to visualize the population in newly acquired territories, whose dynamics might blur and disrupt the social boundaries of British colonial society where racial mixing was not as prevalent as in the Spanish or French territories.

Young appears to have been Brunias’s main patron. He likely also found work among the growing British population, who had economic interests on the islands. They had a taste for the representation of these lands and the people they perceived as exotic. Brunias explores elements of the islands’ social dynamics even while offering idealized images of life in the Caribbean for his British clientele.

Much of his work centers around the representation of local women, particularly women of color. These women become avatars for the manifestation of social and racial boundaries present in colonial society. All of this can be appreciated in the painting in question, with the mixed women in the foreground accompanied by their white children in the care and company of their Black servants toward the background. Brunias deftly represents a scene that may interest and put at ease the British client, with a stratified image of Caribbean people, while alluding to the miscegenation that defined many aspects of society. This racial mixing was seen as representative of the region.

Agostino Brunias, Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape (detail), c. 1770–96, oil on canvas, 50.8 x 66.4 cm (Brooklyn Museum)

Clothes also serve as important indicators of place. The fashion here is distinct from European styles popular at the time, demonstrating the adaptation of clothes to the climate. White and striped linen are abundant in the dresses, as are light materials favored in hot and humid climates. Five of the women wear headwraps to protect their hair. These could be intricate in their design and were worn by women across the socioeconomic and racial spectrum in places like Dominica. The occasional combination of the headwrap with a hat or bonnet point to the mix of European and African styles.

A Caribbean conversation piece

Brunias was an academically trained artist living in Rome when he caught the eye of English architect Robert Adams. Adams recruited him as a draftsman and brought him to London in 1758. There, he worked in Adams’s studio as a decorative painter, until a dispute over pay caused a break in their working relationship. Soon after, Brunias was presented with the opportunity to work with Young in the Caribbean.

His first trip lasted until the late 1770s, when he returned to England for a few years. By 1784 he was back working on drawings for the St. Vincent Botanical Garden. [1] He settled permanently in the Caribbean, dying in Dominica in 1796. Very little is known of the personal details of Brunias’s life, though it is speculated that after his return, he settled and established a family with a woman of color in Dominica. [2]

Brunias appealed to British taste. In Free Women of Color with Their Children and Servants in a Landscape, he borrowed from the British tradition of conversation pieces—often small, informal group portraits or interesting genre scenes that gained popularity in 18th-century England. In these group portraits or multi-figure fictional scenes, the subjects tend to be organized amid a recreational activity, like the family promenade we find here. The little dogs add levity and a certain domestic quality to the composition. An argument could be made that this painting is a family or household portrait in this tradition, though little is known of its origin.

Many of Brunias’s paintings are modest in scale and were destined to decorate domestic spaces. Few of his paintings are portraits and he often returns to the same settings, such as market scenes, dances, domestic interiors, or small landscapes like this one. It must be noted that many of Brunias’s paintings may have lost their original titles, and little is known of why, or for who, they were created. It is clear that Brunias identified a formula that worked in his market—lighthearted genre scenes where the region’s racial mixing was made palatable to a mostly British audience through its stratified representations. Even through this idealized lens, Brunias’s work stands as an important reference for the visualization of race in a British colonial context.