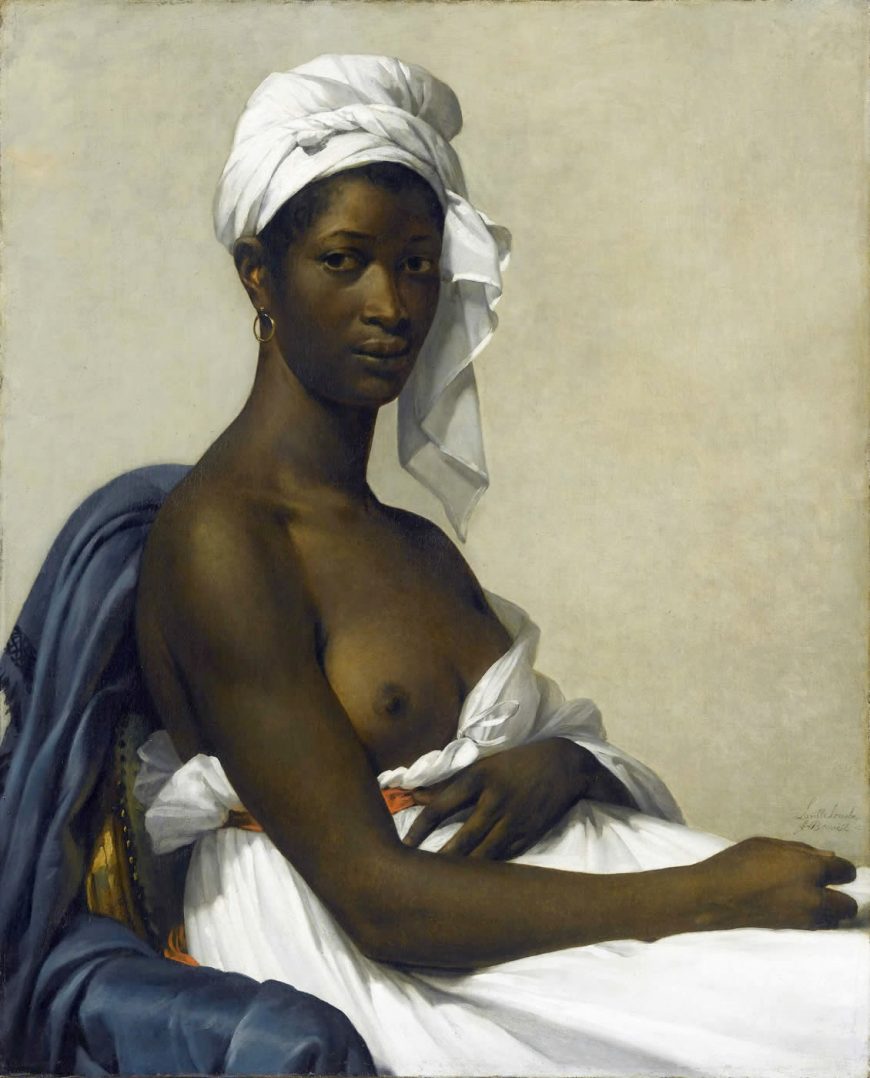

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Madeleine (formerly known as Portrait of a Negress), 1800, oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm (Musée du Louvre)

Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait of Madeleine (formerly known as Portrait of a Negress) hangs today in the Louvre in a gallery devoted to paintings by Jacques-Louis David and his students. It is placed at the center of a wall displaying seven portraits, a location that asserts its importance. In 1800 the work was exhibited in the Louvre for the first time, at the Salon—the state-sponsored presentation of works by contemporary artists. It hung in the Salon Carré, one smallish work on a wall of paintings hung frame to frame, floor to ceiling, as was customary at the time. Contemporary art critics picked it out, but not all were impressed. The critic for a conservative paper derided it as a “noirceur” or “black stain.” Why did this work provoke such a negative response when first exhibited?

Antoine Maxime Monsaldy, “View of the paintings exhibited at the Museum Centrale des Arts in the Year VIII,” 1800, print (Bibliothèque nationale de France). Benoist’s painting can be seen at the center left.

A portrait or an allegory?

Detail, Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Madeleine (formerly known as Portrait of a Negress), 1800, oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm (Musée du Louvre)

The painting shows a young black woman seated in an armchair. Her body is oriented to her left, but she turns to face the viewer with a sober and self-possessed expression. The treatment of her face suggests this is a likeness of a particular individual. Most of her hair is covered in an elaborate white headwrap, and she wears a brilliant white garment that slips from her shoulders to reveal the warm dark skin of her right breast. The background is a plain beige field, but the trim on her chair suggests that she is sitting in a well-furnished interior. The only bright colors in this largely monochromatic work are the red of a ribbon holding the white cloth beneath her breasts and the blue of a shawl draped over the back of her chair.

Benoist’s painting is consistent with the conventions of portraiture and the Neoclassical aesthetic prevailing in France in 1800. The woman’s costume recalls the fashionable dress of the period, and her pose is similar to those seen in Jacques-Louis David’s portraits, such as Madame Raymond de Verninac. The bared breast underlines the contrast of skin and fabric: in portraits, a convincing rendering of flesh tones was crucial, and in the European tradition, as far back as the sixteenth century, the skin of “Ethiopians”—as Africans were commonly called—was considered especially challenging to paint. Benoist’s work is a striking demonstration of her capabilities as a portraitist.

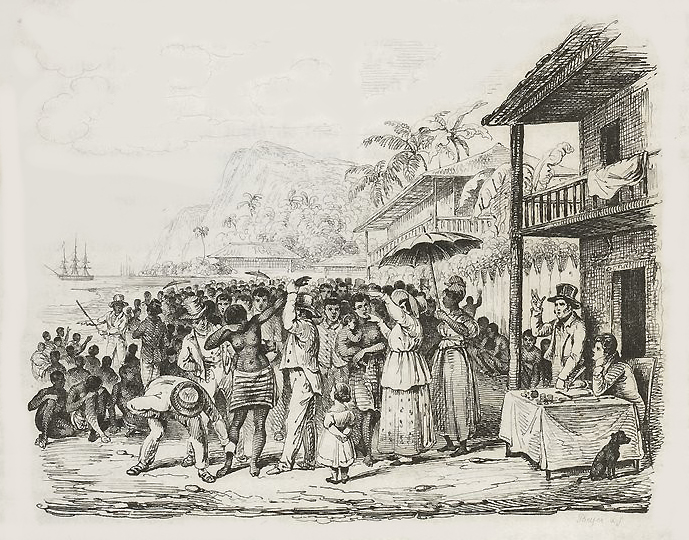

Alcide Dessalines d’ Orbigny, “A Slave Auction, Martinique, c. 1826,” from Voyage pittoresque dans les deux Amériques (Paris, 1836), facing p. 14 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

A respectable woman, however, would have been unlikely to agree to be represented with her breast exposed. The revealing costume of Laville-Leroulx’s black sitter might have recalled, for some viewers, the slave markets in French colonies, where the bodies of black women were inspected by potential buyers. A bared breast was also, however, a motif frequently used in allegories. Elisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun, for example, had incorporated a bare breast in her painting Peace Bringing Back Abundance to evoke the generous riches that are the product of political concord. Other viewers, therefore, might have seen Benoist’s figure as an allegory, especially as her costume included the blue, white, and red colors of the tricoleur flag that had been adopted by the French Revolutionary Government in 1789.

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun, Peace Bringing Back Abundance, 1780, oil on canvas, 103 x 133 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Who was the sitter?

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Madeleine (formerly known as Portrait of a Negress), 1800, oil on canvas, 81 x 65 cm (Musée du Louvre)

Benoist did not provide her sitter’s name, but it was customary to protect sitters’ privacy by using titles such as “Portrait of a Lady” when exhibiting works at the Salon. In this case we know something of the woman’s status and background, if not her identity. Prior to the Revolution, slavery was not authorized on the French mainland. As early as the fourteenth century, King Louis X had decreed that “France signifies freedom” and that slaves setting foot on French soil should be freed. For this reason, when Thomas Jefferson was appointed ambassador to France from the new United States of America, the two slaves he brought with him—Sarah or “Sally” and James Hemings—were legally free while on French soil. Jefferson paid them a wage during their years in Paris, and when he prepared to return home, they renegotiated their status. Happily, recent scholarship has provided the sitter’s first name, Madeleine.

Official decree of 1794, which abolished slavery in the French colonies, from La Révolution française et l’abolition de l’esclavage, vol. 12, p. 55 (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

In 1794, the radical revolutionary government led by the Jacobins and Maxmilien Robespierre extended the domain of liberty by abolishing slavery in French colonies as well as the mainland. French merchants would continue to profit from the slave trade, however, and monarchists in some French territories ignored the regulation, seeking to turn their allegiance to Britain.

Madeleine is thought to have been brought to France from the island of Guadeloupe by the artist’s brother-in-law, a ship’s purser and civil servant. She was likely born a slave in the colony and freed by the decree of 1794, but her actual status may have been ambiguous. Whether she was brought to France as a slave or a servant, she—unlike fashionable women who commissioned their portraits—would have had little influence on how Benoist represented her.

Who was the artist?

We know a good deal more about the artist than the sitter. Marie-Guillemine Laville-Leroulx (Benoist was her married name) was born into a middle-class family. Her father was a civil servant who had failed in business. He believed firmly that his two daughters should be educated to earn their own way—an unusual attitude in the eighteenth century. Marie-Guillemine and her sister first studied painting with Vigée Le Brun and later were among three women whom David took into his studio in the Louvre, challenging concerns about propriety raised by the government minister in charge of the palace.

Laville-Leroulx made her debut at the Salon of 1791, when the revolutionary government opened the exhibition to all artists for the first time. She was ambitious, exhibiting history paintings, which were widely considered beyond women’s capacities. She listed herself as a student of David, even though the artist was a firm supporter of the Revolution, while her family remained loyal to the king. Two years later, she married Pierre Vincent Benoist, who was, like her family, a monarchist. During the Reign of Terror the couple’s life was difficult. By 1800, however, Napoleon I had staged a coup d’etat and installed himself as First Consul of the Directory. With the change in government, Mme Benoist, as she was now known, was ready to take up her public career as an artist.

A politically-charged subject

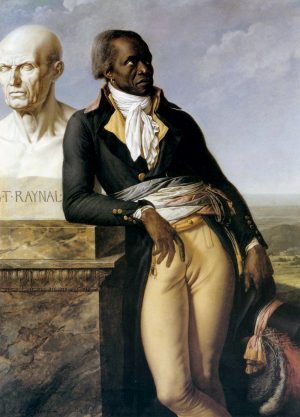

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, Portrait of Citizen Jean-Baptiste Belley, Ex-Representative of the Colonies, 1797, oil on canvas, 159 x 113 cm (Palace of Versailles)

In choosing to paint a woman of color, Benoist selected an unusual subject for a portrait and engaged a politically contentious issue. The only other likeness of an African to be exhibited at the Salon during these years was Anne-Louis Girodet’s Portrait of Citizen Jean-Baptiste Belley, Ex-Representative of the Colonies. Girodet, like Benoist, was a student of David. Belley, who was born in Senegal and enslaved in the French colony of Saint-Domingue, had been freed because of his military service in the French army and was elected one of the colony’s three representatives to the French revolutionary government. Serving from 1793 to 1797, he became well-known as an advocate for racial equality. Girodet’s painting, which juxtaposes Belley’s head with a marble bust of the abolitionist philosopher Guillaume-Thomas Raynal, was understood by visitors to the Salon in 1798 as an argument for emancipation.

Two years later, however, Napoleon I was consolidating his power and began to lay the groundwork for reviving the institution of slavery. He recognized that the Revolutionary government’s decision to free slaves in French territories had not only antagonized citizens of these colonies and other nations, but also had jeopardized the immense profits from the cultivation of sugar that were important to France’s economy. His move was contentious, but it was supported by many who had a vested interest in the economics of slavery, including Benoist’s husband.

Marie-Guillemine Benoist, Portrait of Pauline Bonaparte, Princess Borghese, 1808, oil on canvas, 200 x 142 cm (Musée national du Château de Fontainebleau)

The Salon critic who in 1800 dubbed Benoist’s painting a “black stain” was surely influenced by arguments in favor of reinstating slavery. Twenty-first century viewers are more likely to sympathize with the situation of the woman who sat for Benoist. What was Benoist’s purpose in exhibiting Portrait of Madeleine? In conveying the beauty and humanity of her sitter, was she suggesting that this anonymous woman and others of African descent should be free citizens of the French nation? Or was she simply trying to promote her considerable skills as a portraitist in the tradition of David and Girodet? Since Benoist left no statement to explain her work, we can only infer her intentions on the basis of the painting itself and the historical circumstances surrounding its creation.

In 1802 Napoleon reinstated slavery in France’s overseas colonies. Benoist went on to receive commissions for portraits from Napoleon and several members of his family. After Napoleon was defeated, her husband was awarded an important post in the Restoration government of King Louis XVIII. Marie-Guillemine Laville-Leroulx Benoist—much to her dismay—was forced to relinquish her painting career, which was considered inappropriate for a woman of her position in the increasingly conservative political climate.