Judy Chicago’s landmark installation gives notable women from history a seat at the table.

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974–79, ceramic, porcelain, textile, triangular table 14.63 x 14.63 m (Brooklyn Museum) © Judy Chicago. Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

0:00:05.2 Dr. Steven Zucker: We’re at the Brooklyn Museum looking at one of their most famous and most controversial works of art. This is The Dinner Party.

0:00:12.6 Dr. Beth Harris: The artist Judy Chicago worked with a collective of women in her studio to produce this installation. And entering this space requires walking through a darkened hallway where we see banners overhead that speak to ideas of equality for women. And then we enter this large, dark, very formal space where this triangle of tables is spotlit. Specifically, what we’re looking at are place settings for 39 women. This includes goddesses and also historical figures, 13 on each of the three tables. So we immediately have this idea of the Last Supper, of something that’s sacred.

0:00:56.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: The artist spoke to being inspired by images of the Last Supper, but she realized quickly that she wanted to celebrate more than 13 women, and even 26 wasn’t enough. 39 was what she could accommodate at the table, but that wasn’t enough. And so if we look at the floor, these tiles are inscribed with the names of important women through history in gold, and there are 999 of them, and so an opportunity to at least include that larger group.

0:01:24.4 Dr. Beth Harris: And so we immediately have the idea of giving these women, literally, a place at the table, a place in history, a recognition of their achievements and of the challenges that they faced.

0:01:37.0 Dr. Steven Zucker: What we’re looking at is the result of many hours of labor uncovering the history of women through time, histories that had been largely neglected.

0:01:47.3 Dr. Beth Harris: And also researching historical artistic techniques.

0:01:51.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: This isn’t painting on canvas. This isn’t marble sculpture. None of this is fine art in the traditional sense. The artist is clearly referencing art that had been associated with women. That is the painting of ceramics, embroidery, and needlework more generally. But she’s creating an extraordinary and grand statement. This is clearly fine art.

0:02:13.8 Dr. Beth Harris: Each woman gets a place at the table, very specifically created for them. The gold, the embroidery, the white cloth, the runners, all speak to the idea of giving these women their due.

0:02:27.4 Dr. Steven Zucker: Judy Chicago tells a story. She was an undergraduate in college. She was taking a history class. The syllabus was filled with the great men of history. But the professor had promised that the last session would be devoted to women and their impact. And she waited all semester for this. When that day came, the professor simply said that women had had no impact. She made at that point a kind of commitment to uncover the history of women, and she looks at The Dinner Party as very much the culmination of that research.

0:02:56.1 Dr. Beth Harris: This is a large part of what second wave feminism or feminism in the 1970s was about. It was recovering the history of women that hadn’t been told.

0:03:06.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: The aspect of this installation that is by far, in a way, its most controversial is the imagery that we see in the plates themselves.

0:03:14.3 Dr. Beth Harris: Most of the plates contain vaginal imagery. This is a historical moment when women are embracing a kind of freedom that had been unimaginable in the 1950s and began to emerge slowly in the 1960s.

0:03:28.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: At a time when minimalism and conceptual art had been dominant, to bring art back to the body was a radical step. And this was very upsetting to the political right as well as to the fine art establishment.

0:03:43.1 Dr. Beth Harris: But when this work was exhibited, when it was completed in 1979, hundreds of thousands of people turned out to see it. It obviously touched a nerve for many, many women. However, the institutions of the art world felt very differently.

0:03:58.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: So let’s focus on one place setting.

0:04:00.2 Dr. Beth Harris: We’re standing in front of the place setting for Mary Wollstonecraft, the author of a very early feminist book called A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, a polemical tract that argues for the fundamental equality of women.

0:04:16.3 Dr. Steven Zucker: And if we look directly below the place setting, we can see one of those inscribed names in gold, and it reads Mary Shelley. This was her daughter and, of course, the author of Frankenstein. The place setting itself feels very appropriate to the late 18th century.

0:04:31.3 Dr. Beth Harris: Well, it looks to me like the kind of embroidery that women in the late 18th century were actually doing. And it shows a variety of wonderful techniques. And the embroidery is in some places very flat, in some places very three-dimensional.

0:04:46.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: But the delicacy and the propriety of the 18th century is shattered when we look to the top of the place setting, sculpted into the surface of the plate is this vulvic form with greens and reds and yellows.

0:04:59.6 Dr. Beth Harris: In addition to its vaginal form, it gives us the idea of something unfolding. And in that way, it feels to me to be very appropriate to this emerging of a feminist consciousness in the late 18th century.

0:05:12.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: What’s interesting is that as we reach this last turn of the table, that is the part of the installation that is devoted to the modern world, the plates take on a three-dimensional quality. They begin very subtly with just a little bit of a raised edge. And then it seems with the plate devoted to Herschel just to the left, we see a part of the plate just lifting up. And we have that even more emphatically in this plate.

0:05:38.5 Dr. Beth Harris: Above the plate, we see scenes that tell us about Mary Wollstonecraft’s life, first as a teacher, as a writer.

0:05:45.1 Dr. Steven Zucker: But this is only part of the story that the runner tells. The far side shows the tragic end of the author’s life.

0:05:51.6 Dr. Beth Harris: Mary Wollstonecraft died from complications after childbirth. And here we see a scene in a bedroom where Mary Wollstonecraft is on a canopied bed with her husband, William Godwin, on one side and her first daughter on the other.

0:06:06.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: It’s such an upsetting image. We see these pristine white linens. They’re stained with blood and Wollstonecraft shown in real distress.

0:06:15.3 Dr. Beth Harris: Over the course of many years while Judy Chicago was working on this piece, several hundred women also worked alongside her. And the woman who was working on this part of the runner talked about an interesting conversation that she had with Judy Chicago. Judy Chicago came up to look at the work and pointed out that Mary Wollstonecraft looked too relaxed. And at Judy Chicago’s insistence, the artist who was working on this restitched the face to give Mary Wollstonecraft a haggard expression using Judy Chicago’s technical drawing as a guide.

0:06:48.7 Dr. Steven Zucker: And this is a wonderful reminder that what Judy Chicago had done was created almost a kind of medieval workshop. That is to say, while hundreds of women worked on various aspects of this installation, Judy Chicago retained creative control.

0:07:02.7 Dr. Beth Harris: It’s so interesting to see visitors to this installation. Everyone walks slowly around the tables, reads the names, looks at the imagery. Some names are familiar, some aren’t, but there is a kind of quiet procession around the table that seems really fitting to its subject matter.

Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974–79, ceramic, porcelain, and textile, 1463 x 1463 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

A Place at the Table

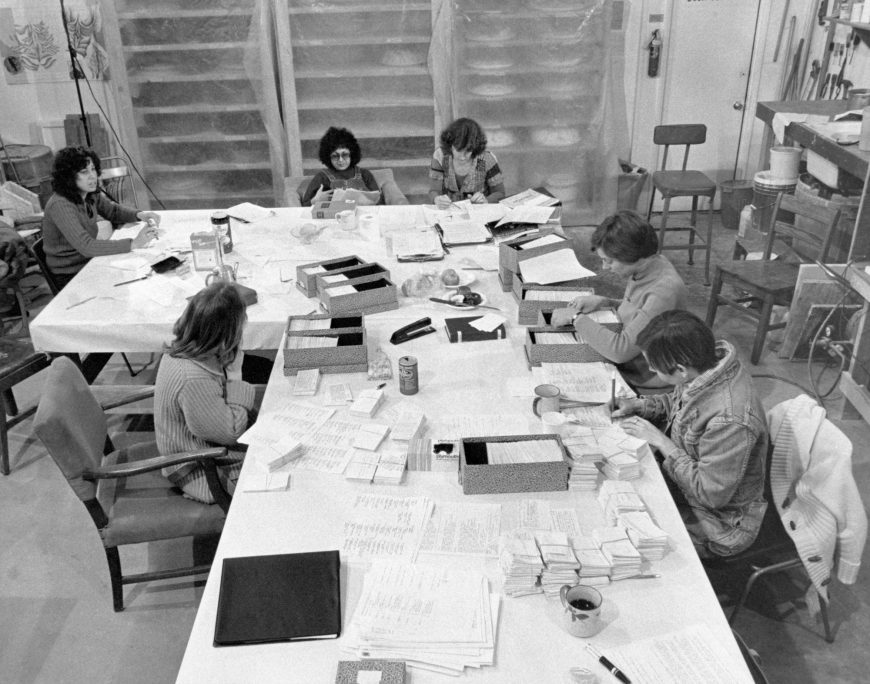

The Dinner Party Research Team, Santa Monica, California (Through the Flower Archive) © Judy Chicago

The Dinner Party is a monument to women’s history and accomplishments. It is a massive triangular table—measuring 48 feet on each side—with 39 place settings dedicated to prominent women throughout history and an additional 999 names are inscribed on the table’s glazed porcelain brick base. This tribute to women, which includes individual place settings for such luminary figures as the Primordial Goddess, Ishtar, Hatshepsut, Theodora, Artemesia Gentileschi, Sacajawea, Sojourner Truth, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Emily Dickinson, Margaret Sanger, and Georgia O’Keeffe, is beautifully crafted. Each place setting has an exquisitely embroidered table runner that includes the name of the woman, utensils, a goblet, and a plate.

The Dinner Party was intended to be exhibited in a large, darkened, sanctuary-like room, with each place setting individually lit, making it look as though it is composed of thirty-nine altars. The 999 names, written in gold, gleam softly, suggesting a hallowed or liminal space. 5 years in the making (1974–79) and the product of the volunteer labor of more than 400 people, The Dinner Party is a testament to the power of feminist vision and artistic collaboration. It was also a testament to Chicago’s ability to create a work of art that spoke to people who had not previously been a part of the art world. When the exhibition opened at the Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco in March of 1979, it was mobbed. Judy Chicago’s accompanying lecture was completely sold out.

Empress Theodora’s place setting (detail), Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974–79, ceramic, porcelain, and textile, 1463 x 1463 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Although critics praised the table runners, they ignored or disparaged the plates. These ceramic objects, which become increasingly three-dimensional during the procession from prehistory to the present in order to represent women rising, look somewhat like flowers and butterflies. They also resemble female genitalia, which many people found disturbing. Writing for the feminist journal Frontiers in 1981, Lolette Kuby was so taken aback by the plates’ forms that she suggested that Playboy and Penthouse had done more to promote the beauty of female anatomy than The Dinner Party ever could.

Mary Wollstonecraft’s place setting (detail), Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974–79, ceramic, porcelain, and textile, 1463 x 1463 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Kuby’s distaste for pudenda was echoed more forcefully a decade later, when Chicago attempted to donate the artwork to the University of the District of Columbia. Chicago was forced to withdraw her donation after the U.S. Senate threatened to withhold funding from UDC if they accepted what Rep. Robert Dornan characterized as “3-D ceramic pornography” and Rep. Dana Rohrabacher dismissed as a “spectacle of weird art, weird feminist art at that.” It was not until 2007 that The Dinner Party, an icon of feminist art, would find a permanent home in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art in the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

Feminist Education

What drove Chicago to embark on such a large and controversial feminist project? She was inspired, in part, by her pioneering work in feminist education. She started the Feminist Art Program at California State University, Fresno in 1970. The following year she founded the Feminist Art Program (FAP) at the newly established California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) with the abstract painter Miriam Schapiro. The galleries were still under construction when Chicago arrived at CalArts, so the FAP had their exhibition in an abandoned mansion that was slated to be demolished shortly after. The resulting installation, Womanhouse, was a testament to Chicago’s method of teaching, which begin with consciousness raising and then progressed to realizing a message through whatever medium was most suitable, whether it was performance, sculpture, or painting.

Primordial Goddess’s place setting (detail), Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974–79, ceramic, porcelain, and textile, 1463 x 1463 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

While at CalArts, Chicago and Schapiro developed the idea of “central core imagery,” arguing in a 1973 article published in Womanspace Journal that many women artists making abstract art unconsciously gravitated towards imagery that was anti-phallic. By the time she began working on The Dinner Party, Chicago had come to believe that central core imagery, which celebrated feminine eroticism and fertility, could be used to challenge patriarchal constructions of women. For Chicago, there existed an irreducible difference between men and women, and that difference began with the genitals. Chicago would eventually put vaginal imagery front and center in The Dinner Party.

Right Out of History

After several years of work establishing various feminist art programs in Southern California, Chicago was eager to get back to making her own artwork and resigned from teaching in 1974. Her experience with Womanhouse inspired her to embrace materials that had traditionally been associated with women’s crafts, such as embroidery, weaving, and china painting. She was determined to make a monument to women’s history using china-painted plates alluding to thirteen specific figures, which she originally planned to hang on the gallery wall. However, she soon realized that there were many more women that she wished to include, and the initial conception of the piece expanded to a large-scale installation with 39 place settings.

Sojourner Truth place setting (detail), Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974–79, ceramic, porcelain, and textile, 1463 x 1463 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

An important component of the piece was the educational material that represented the years of research that had been conducted by Chicago’s volunteer staff, led by art historian Diane Gelon. The Dinner Party was accompanied by a book of the same title (published by Anchor Books in 1979 and designed by Sheila Levrant de Bretteville) that included the stories behind all 1,038 names. Filmmaker Johanna Demetrakas documented the monumental effort that it took to make this installation in her film Right Out of History: The Making of the Dinner Party.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s place setting (detail), Judy Chicago, The Dinner Party, 1974–79, ceramic, porcelain, and textile, 1463 x 1463 cm (Brooklyn Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Not Exactly Playboy or Penthouse

In order to understand The Dinner Party, we must keep in mind that the sculptural painted plates were intended to be metaphors rather than realistic representations. Take, for instance, the final place setting on the table—the one for Georgia O’Keeffe. This plate is the most sculptural piece in the installation. Pink and greenish gray swirls and folds radiate out from a central core framed by fleshy looking folds that seem to have been deliberately spread apart in order to reveal what should be a hidden entrance. The plate can be read as suggestive of female genitalia, but its forms also recall the shape of a butterfly and the reproductive organs of flowers. O’Keeffe was famous for her abstracted paintings of flowers, and and the plate is an homage to some her best-known works, such as Grey Lines With Black, Blue, and Yellow (1923) and Black Iris III (1926), both of which have a central opening framed by folds, or Two Calla Lilies On Pink (1928), which has a similar color palette to the O’Keeffe plate.

Chicago’s decision to use vaginal imagery has proven to be powerful. The Dinner Party, having survived rejection, critical dismissal, and political grandstanding, is now considered a key work of contemporary art, and is permanently installed in a dedicated space at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum.