Reactivation of The Clothesline by Mónica Mayer in the Contemporary Art University Museum, Mexico City, May 2016, in the context of the exhibition “When in Doubt… Ask: A Retrocollective Exhibit of Mónica Mayer” (photo: Corderokaren, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Hundreds of pink paper postcards

In 1978, artist Mónica Mayer distributed hundreds of pink paper postcards to a diverse group of women in Mexico City; each card included a statement that was meant to be completed by the participants: “As a woman, what I most hate about the city is.” Most of the completed responses highlighted experiences of sexual harassment within the urban environment of Mexico City. Mayer brought attention to the untold stories and silenced voices of urban women as her contribution to “New Tendencies,” an exhibition curated by Mathias Goeritz for the Museum of Modern Art in Mexico City.

At the museum, the artist, who is from Mexico, presented the postcards held in place by clothespins hung from rows of pink string that were placed within a brightly-colored pink frame. By employing a color traditionally associated with femininity in multiple elements of the installation, Mayer underscored how her art project focused on women’s experiences, a topic often ignored by art institutions. The title of the installation, The Clothesline, deliberately referenced the domestic labor traditionally described as “women’s work” in Mexican society.

Several women visiting the exhibition wrote additional responses in the cards, spontaneously participating in the artistic process. Mayer’s installation — constructed out of simple materials — string, paper, and clothespins — shattered the silence that surrounded experiences of sexual violence in the city, allowing women to voice their experiences within the gallery spaces of the Museum of Modern Art. The hundreds of responses revealed how sexual violence was a large-scale social problem faced by women every day.

Intersections with Mexican feminism(s)

Mayer produced The Clothesline after participating in the burgeoning forms of feminist activism that flourished in Mexico City throughout the 1970s. This diverse social movement sought women’s emancipation in Mexican society, though individual activists and feminist organizations disagreed on how to achieve this goal. For instance, feminist groups debated whether they should cooperate with the Mexican government to change the country’s laws, or whether they should establish themselves as an independent movement that resisted any form of institutionalization.

Despite the different perspectives espoused by individual feminist organizations, several activists argued that the most pressing issues faced by contemporary women were sexual violence and reproductive rights. Members from different groups came together to establish the Coalition of Feminist Women in 1976 as a way to tackle these issues. Describing her participation in this coalition, Mayer noted the passionate debates that developed between activists: “violent discussions, radical attitudes, [and] painful recriminations were the norm.” Still, the artist also emphasized how these activists banded together to provoke social changes: “A wonderful memory I have from those days is the demonstration we held in front of the Senators Building in December of 1977, demanding the liberalization of abortion” [1]— underscoring the passion and diversity of feminist activism in Mexico.

Through The Clothesline, Mayer developed a participatory artistic installation that resonated with the issues raised by her fellow feminist activists. The project served as a prominent example of feminist art, since it encouraged audience members to question the ways in which gender inequality and sexual violence affected the individual lives of countless women. The collaborative methods Mayer employed in the production of the work also resonated with the egalitarian ideals of her fellow feminist activists. In a later description of the project, the artist argued that “the artwork is not the clothesline itself, but the interaction that occurs when you request responses and what happens when the public gets to read them.”[2] Mayer emphasized her position as both a creator and collaborator of the installation.

Transnational connections

After her participation in the exhibition, “New Tendencies,” Mayer continued exploring intersections between artistic practice and feminist activism. In 1978, she traveled to Los Angeles to study at the Feminist Studio Workshop (FSW), the first independent center for feminist artistic instruction in the United States. Artist Judy Chicago, art historian Arlene Raven, and graphic designer Sheila de Bretteville established the FSW in 1973. The school was part of the larger Los Angeles based institution known as the Woman’s Building.

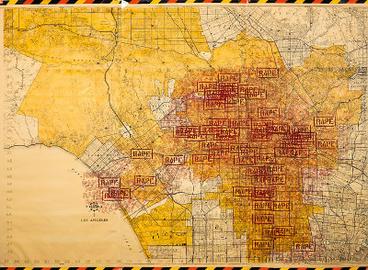

A map of Los Angeles marked with large red “RAPE” stamps to indicate places where rapes had occurred. Created by Suzanne Lacy for Three Weeks in May, an activist performance art work that took place from May 8 to May 24, 1977, © Suzanne Lacy (photo)

As a student at the FSW, Mayer found Suzanne Lacy’s artistic projects that explored the connections between public art, activism, and feminism particularly intriguing. In 1977, for instance, Lacy developed Three Weeks in May. As part of this project, the artist “went to the Los Angeles Police Department’s central office to obtain confidential rape reports from the previous day.”[3] Lacy then identified the locations of these crimes by stamping the word “RAPE” in a large-scale map of Los Angeles. The artist displayed this map at a public shopping center; she also presented a second map that showed the location of resource centers for women who had experienced sexual violence.

In Los Angeles, Mayer further considered the artistic potential of her clothesline installation. The Clothesline: Los Angeles emerged in 1979, when Communitas—a group from Ocean Park, Santa Monica—asked Lacy to explore the forms of violence experienced by women in that neighborhood. Lacy developed Making It Safe, a project in which “[s]he and her collaborators distributed leaflets, created a series of events, speak-outs on incest, small dialogues, and curated an art show in thirty windows of the local commercial district.”[4] As part of Making It Safe, Mayer redeployed her earlier clothesline project. As described by Mayer, the questions in this clothesline “revolved around the perceptions of safety and danger by women in the community of Ocean Park, including their proposals to feel safer.”[5]

By focusing the questions on the experiences of a particular community, the artist suggested how different geographic and cultural contexts shape the experiences of women. Instead of considering women as a monolithic group, the artist prompted participants to describe how living within Ocean Park shaped their understanding of violence and safety. Since both of the clotheslines alluded to the problem of sexual violence, the art project suggested how different communities of women, whether in Mexico City or Los Angeles, could establish alliances between them.

Legacy

Mayer’s clotheslines of the late 1970s are only a small glimpse of her extensive career as a feminist artist that has lasted for more than forty years. After her studies in the FSW, Mayer was a founding member of feminist art collectives such as Women Scribes and Portraitists and Black Hen Powder in Mexico City. The foundational project of The Clothesline continues to engage audiences throughout her home country and abroad. In the late 2010s, Mayer developed new versions of the project in Mexico City (2016), Washington, D.C. (2017), Hermosillo, Mexico (2018), Buenos Aires, Argentina (2018), and Portland, OR (2018). Each of these clotheslines reveal how Mayer challenges gender inequality across the globe, continuing the goals of social transformation espoused by Mexican feminist activists of the 1970s.