The textile is laid out on the street in Bogotá, Colombia, while the artist and assistants work on it. Olga de Amaral, El gran muro (The Great Wall), 1976, brown bast fiber warp, polychrome wool, horse hair, and cotton twill, 768 x 48 inches (courtesy the artist and Portman Archives, Atlanta)

Panel 2A laid out on the floor (detail). The varied textures of the wool and horsehair are evident. Olga de Amaral, El gran muro (courtesy the artist and Portman Archives, Atlanta)

In the photograph, we see a portion of Olga de Amaral’s El gran muro (The Great Wall) resting on the ground. From this vantage point, the artwork could be mistaken for an orderly pile of autumn leaves. A closer look, however, reveals that its individual elements are, in fact, rectilinear strips of various lengths and widths. If we could get even closer, we would see that the strips are woven from wool and coarse horsehair in colors ranging from dark reds and warm yellows to pale blues and chalky grays. The artist and her assistants are sewing the woven strips to cotton twill backing in densely piled and irregular groupings that are, in fact, meant to evoke cascading leaves or vines. When finished, El gran muro took the form of two six-story tall wall hangings.

The fiber art movement

Amaral’s El gran muro is an exemplary object of a fiber art movement that crisscrossed nationalities, generations, and geographies in the 1970s. Artists trained in textiles traditions began to explore new ways of working with fibrous materials such as wool and sisal. Originally referred to as la nouvelle tapisserie (new tapestry), the movement brought new visibility to weaving as an art form. However, fiber artists (such as Amaral, Magdalena Abakanowicz, and Sheila Hicks) abandoned the flat structures and pictorial designs associated with European tapestry conventions. Interested in the intrinsic properties of their materials and the possibilities of scale, display, and space, they produced radically abstract hangings and dense, three-dimensional forms using woven and off-loom methods (such as plaiting, coiling, and knotting).

El gran muro was commissioned by the U.S. architect John C. Portman. Amaral designed it specifically for the atrium of his firm’s newly opened Peachtree Plaza (now Westin) hotel in Atlanta. Commissions of this kind played a prominent role in supporting artists working in fiber. Despite some significant museum and gallery exhibitions, the mainstream art world largely ignored this movement. This bias contributed to the long-standing perception that objects made from yarn and thread belonged to the realm of ornamental or practical “craft” rather than “fine art.” The association of craft with women’s domestic handiwork also reinforced deeply entrenched gender hierarchies that marginalized fiber artists. By contrast, architects and interior designers appreciated how large-scale textiles could hold their own in expansive postmodern buildings of glass and concrete. As fiber artists fulfilled commissions for the lobbies of hotels and corporate and government buildings, the details of the architectural spaces became an integral component of the work’s conception. The story of Amaral’s El gran muro reveals the benefits—and pitfalls—of this relationship between contemporary fiber art and architectural site-specificity.

Olga de Amaral studied in the graduate program at Cranbrook during the 1954–55 academic year. Cranbrook Academy of Art graduate degree exhibition, displaying textiles and ceramics, 1955 (photo: © Harvey Croze, courtesy of Cranbrook Archives, Cranbrook Center for Collections and Research)

Weavings in space

As the only South American artist associated with the fiber art movement, Olga de Amaral’s approach reflected the overlapping contexts in which she studied and worked. The artist was born in 1932 to a middle-class family in Bogotá, Colombia. After training in architectural drafting and design, she did post-graduate work in the textile department at Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, where she studied under Finnish weaver and textile designer Marianne Strengell. Cranbrook emphasized modernist design principles and interdisciplinary studies. Amaral’s time there proved transformative. It was an artistic environment, she recalled, that encouraged self-direction and innovation.

After Amaral returned to Bogotá in the mid-1950s, she and her husband, artist Jim Amaral, established a design studio that employed local artists to produce textiles for architects and interior designers. Above all, and as she moved her work from the walls to the floor and back again to the walls, Amaral harnessed her early training as an architect concerned with defining and activating space. She wanted her weavings to be integrated into the architecture in a complementary relationship. She also wanted her works to encourage a mobile viewer through their placement. Amaral achieved these goals with El gran muro.

El gran muro in situ

At the time of its construction in 1976, the Peachtree Plaza Hotel was the tallest hotel in the world and notable for its soaring, cylindrical atrium. Although dominated by rough concrete and smooth glass surfaces, the building was designed with other textures as well. These included wood and metal accents, water features, and an abundance of potted plants.

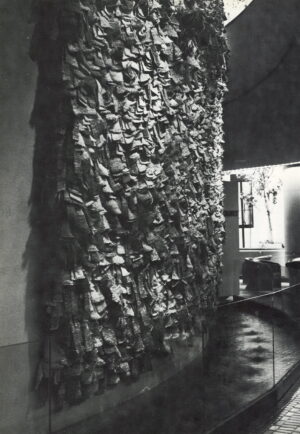

Olga de Amaral, El gran muro (The Great Wall) in John C. Portman, Peachtree Plaza (now Westin) hotel (Atlanta)

Amaral’s two separate hangings, each composed of eight overlapping panels, were installed against the curved walls enclosing the elevator banks in the atrium’s center. Visible from multiple points around the space, they softened but did not distract from Portman’s architecture. The thick relief effect of the woven strips may even have acted like an acoustic panel dampening the noises of the busy hotel lobby.

The successful integration of El gran muro into Portman’s interior décor is the mark of a close understanding between artist and patron. The site-specificity of Amaral’s artwork, however, was also a contributing factor in its demise. After two decades, the weavings fell victim to hotel renovations. When the atrium was redecorated, the panels were disassembled; several were destroyed due to wear and tear, and others were rolled up and placed in storage.

Olga de Amaral, El gran muro (The Great Wall) in John C. Portman, Peachtree Plaza (now Westin) hotel (Atlanta), reproduced in Mildred Constantine and Jack Lenor Larsen, The Art Fabric: Mainstream (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1981)

Textile commissions are by no means the only kind of art to suffer this kind of fate. Yet the centuries-long connection of woven tapestries to the architectural spaces in which we conduct our daily lives continues to make them especially vulnerable. Buildings change ownership, décor tastes shift, and the economic and logistical challenges of cleaning large textiles have led to many contemporary fiber art commissions being removed, lost, or destroyed. Consequently, an important chapter of textile history is at risk of disappearing with them.

Lost (and found)

Fortunately, the story of El gran muro doesn’t end there. In 2022, several panels were gifted to museums in the U.S. While the monumentality and architectural specificity of Amaral’s weavings is now only available through photographic documentation, the preservation of these sections allows us to continue to study the work’s unique material construction. “To weave a rock” was a cryptic set of instructions the Colombian artist once gave to a weaving class. Her students were initially perplexed but eventually understood that Amaral was pushing them to explore unorthodox methods and outcomes. That weavings can be flat and volumetric, ordered and spontaneous, surface and form: these are some of the lasting lessons bound up in El gran muro.