Latin American art: an introduction

Read Now >Chapter 69

Latin American modernisms

Introduction: What characterizes Latin American Modern art?

The 20th century was a period of tremendous artistic innovation, political change, and social transformation in Latin America. Latin American artists explored issues native to their local contexts while engaging and contributing to avant-garde art movements that developed internationally.

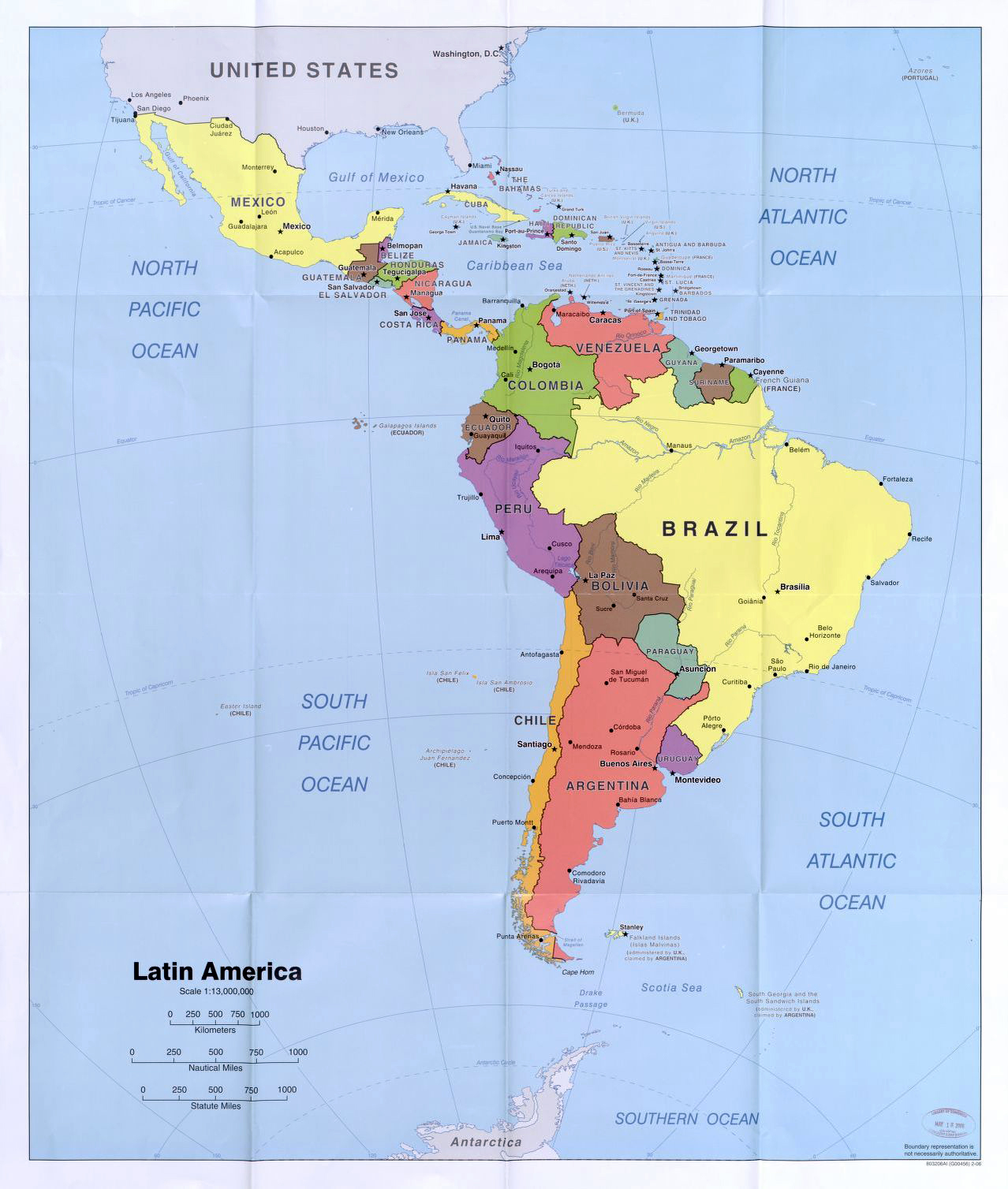

Map of Latin America (published Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency, 2006; now Library of Congress)

Latin America is a vast and diverse region, and this chapter will cover several, but not all, of the art movements that took place in the 20th century in this area. The complexities of the term and the geography of this region is discussed below in the essay “Latin American Art: An Introduction.”

An example of a colonial era painting. Master of Calamarca, Archangel with Gun, Asiel Timor Dei, before 1728, oil on canvas and gilding, 160 x 110 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, La Paz, Bolivia)

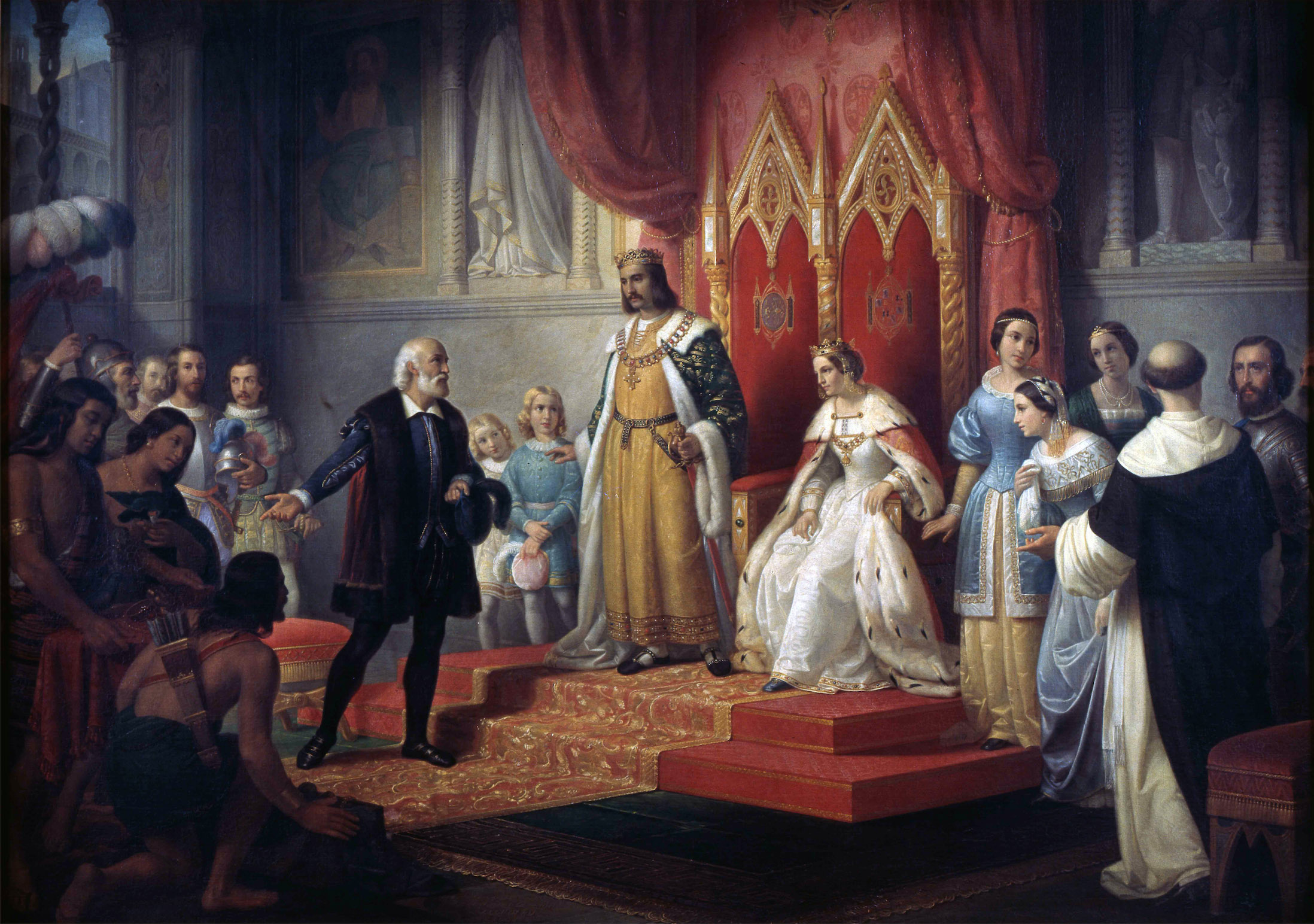

Artists in 20th-century Latin America grappled with reconciling history and local artistic traditions with notions of “high art” and what it meant to be industrialized and modern. Artists often rejected the naturalistic, biblical narratives of earlier colonial art (c. 1521–1821) and the conservatism of nineteenth-century academic art (art produced under the influence of European academies of art) in favor of exploring alternative modes of expression that challenged stylistic and thematic boundaries.

An example of an academic painting, made at the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City. Juan Cordero, Christopher Columbus at the Court of the Catholic Monarchs, 1850, oil on canvas, 180.5 x 251 cm (Museo Nacional de Arte, INBA (MUNAL), Mexico City)

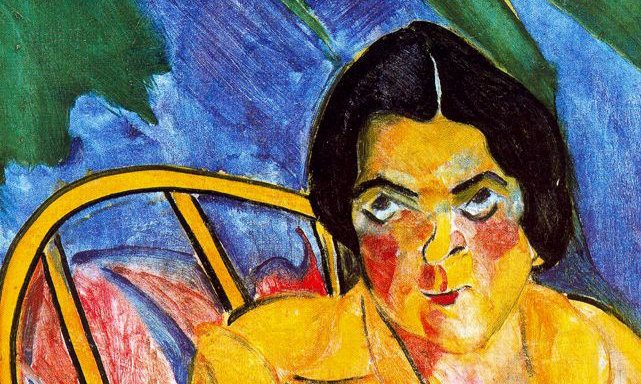

In general, artists moved away from creating illusionistic representations that mimicked the “real” world. Instead, they produced artworks that shunned rational perspectival space favoring simple shapes, bold colors, and distorted angles that emphasized the flatness of the picture plane. Their subject matter moved away from the predominant Christian themes of years past in favor of representations of the complexities of everyday, modern life in 20th-century Latin America.

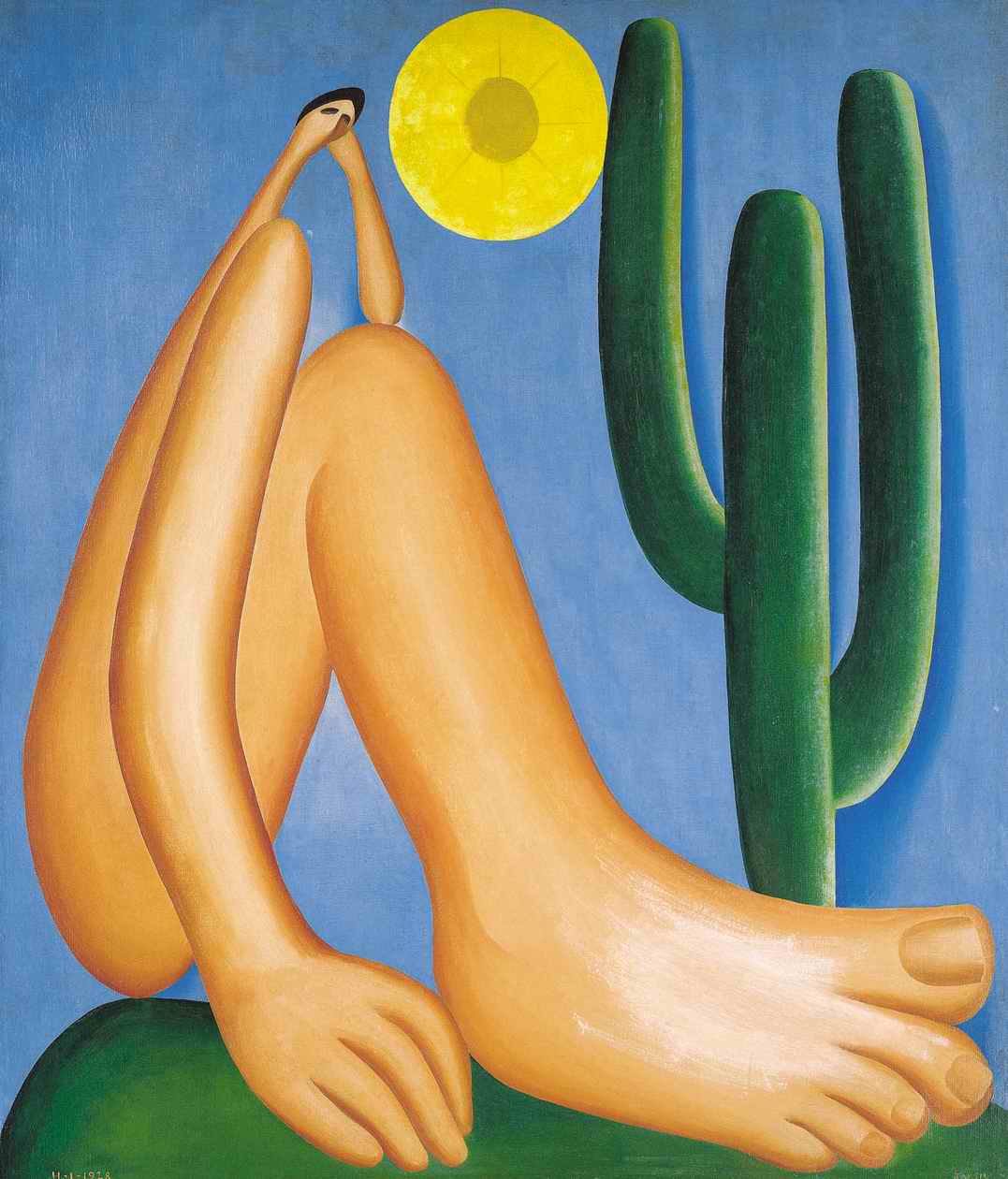

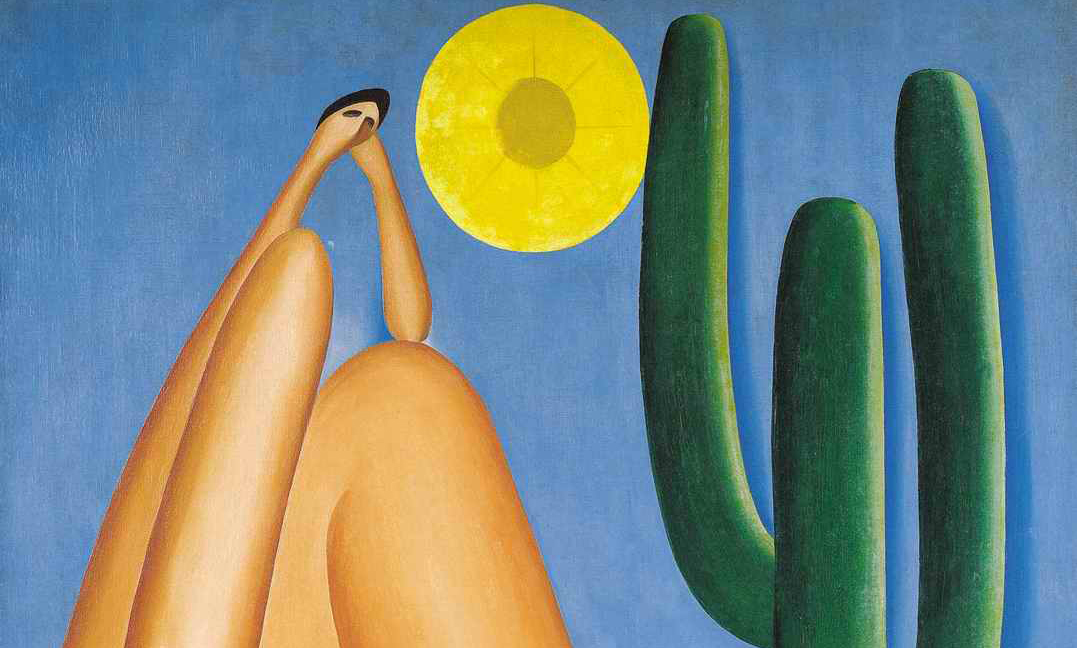

Tarsila do Amaral, Abaporú, 1928, oil on canvas, 85 cm × 73 cm (Museum of Latin American Art, Buenos Aires)

Throughout Latin America there was a push and pull with ideas, styles, and techniques coming from Europe and the United States. Artists maintained strong ties and sentiments to their own nations, while experimenting with and adapting international avant-garde styles.

Read an introductory essay

/1 Completed

Early Vanguards

There was great variety and experimentation in the art produced by Latin American artists in the early 20th century and there is no one style that ties these artists together. For the most part, artists sought a rupture with the past, rejecting the colonial period and academic culture of the 19th century. Many artists traveled to Europe and actively engaged with 19th- and 20th-century avant-garde movements, such as Impressionism, Fauvism, Expressionism, and Cubism, and adapted them to suit their own ideologies and experiences.

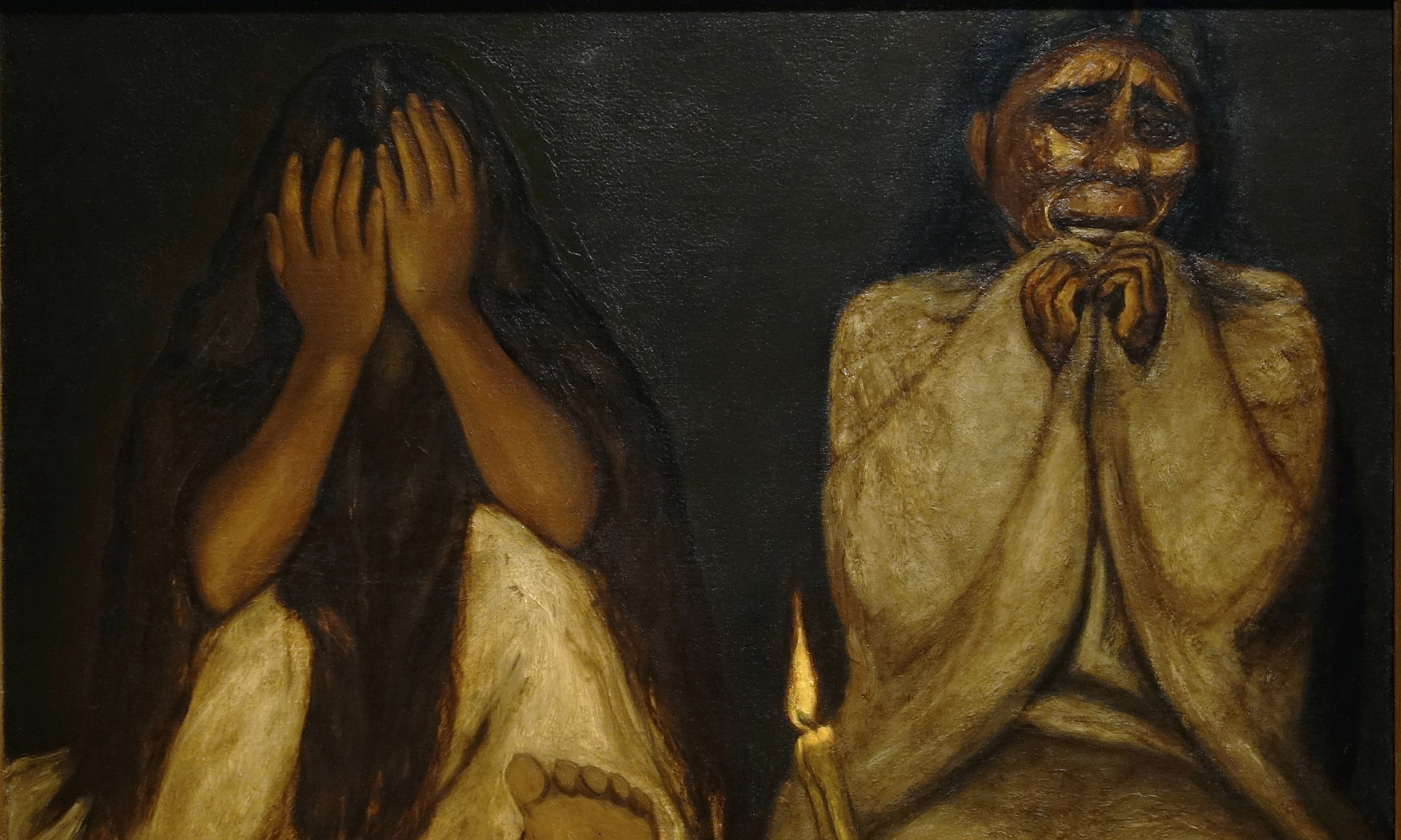

Francisco Goitia, Tata Jesucristo, c. 1925–27, oil on canvas (Museo Nacional de Arte, Mexico City)

Some countries, such as Mexico, underwent great political instability and a revolutionary war, which may be evident in the sense of despair and suffering we see in the paintings of artists like Francisco Goitia. In Brazil, an organized event, the famous Semana de Arte Moderno (Modern Art Week), celebrated the centennial of Brazilian independence from Portugal and ushered in the arrival of Brazilian Modernism. Negating official academic art and literature, artists such as Anita Malfatti, Emiliano Cavalcanti, and Tarsila do Amaral, challenged traditional modes of representation, creating their own modern visual languages that were often rooted in Indigenous and African cultures.

Watch a video and read essays about early vanguards

Francisco Goitia, Tata Jesucristo: An image of universal suffering confronts us directly.

Read Now >

The origins of modern art in São Paulo: An introduction to the origins of Brazilian modernism.

Read Now >

Tarsila do Amaral, Abaporú: An artist who was actively engaged in the development of a new visual language of Brazilian modernism.

Read Now >/3 Completed

Monumental Art: Painting the Walls

At the end of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Mexico was ruled by the dictator General Porfirio Díaz. His reign, known as the Porfiriato (1876–1910), was a period characterized by centralized state power, foreign investment, and the oppression of the lower classes. His long-standing dictatorship provoked the Mexican Revolution (1910–20) where the Mexican people sought to challenge the inequities of the colonial and post-Independence periods by fighting for agrarian, social, and political reforms. The Mexican Muralist movement was spurred by the Mexican Revolution and flourished in the 1920s–30s.

José Clemente Orozco, The Trench (center arch), San Ildefonso College courtyard, begun 1923, Mexico City

The Mexican muralists believed that monumental, public art could be an instrument for political and social change. The movement was supported and championed by the Mexican government. José Vasconcelos, Minister of Education, commissioned the muralists to paint the walls of government buildings. He gave the artists tremendous freedom in choosing the subject matter and style of their murals.

Murals (Maya), c. 792 C.E., room 3, building 1, Bonampak, Chiapas, Mexico

There had been a tradition of murals in pre-Columbian Mexico (long before the European invasions and colonization). By repurposing an ancient art form, the muralists honored their forebears. The Mexican muralists sought to represent mexicanidad, a term used to connote the Mexican nation, its traditions, and identity. They championed the marginalized Indian and desired to re-represent history by telling stories that had been suppressed and ignored during the colonial and post-Independence periods. They were often critical, not only of Spanish colonization and corrupt 19th-century leaders such as Porfirio Díaz, but also of the outcomes of the Revolution itself. Many of the Mexican muralists favored figurative representation, which was better suited to representing legible historical narratives and making political statements, although several pushed the boundaries toward more abstract, expressionistic, and experimental compositions.

North wall (detail), Diego Rivera, Detroit Industry murals, 1932–33, twenty-seven fresco panels at the Detroit Institute of Arts (photo: quickfix, CC BY-SA 2.0)

There were many artists who participated in what is now known as the Mexican Muralist movement, but three of the most well-known Mexican muralists, termed “los tres grandes” (the 3 Greats), are Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Although a majority of their murals were completed throughout Mexico, the muralists also traveled to the United States where they received patronage and recognition for their public, socially and politically pointed art. In turn, the Mexican muralists had a notable impact on U.S. artists such as Jackson Pollock, Charles White, and Hale Woodruff.

Watch videos and read essays about mural painting

Mexican Muralism and Los Tres Grandes: An introduction to David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, and José Clemente Orozco.

Read Now >

Diego Rivera, The History of Mexico: Diego Rivera’s murals at the National Palace offer a sweeping history of Mexico.

Read Now >

Diego Rivera, Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park: Rivera includes 400 years of history here, and guarantees that the stories normally edited out are included.

Read Now >

Diego Rivera, Man Controller of the Universe: It is a recreation of a mural, Man at the Crossroads, commissioned John D. Rockefeller Jr. in New York City, which was begun and then destroyed.

Read Now >

José Clemente Orozco, Dive Bomber and Tank: Painted in front of MOMA visitors in 1940 as WWII waged on, Orozco’s mural depicts the triumph of war over humanity.

Read Now >/5 Completed

Everyday Life: Social Realities

Despite Independence and Revolutionary movements which fought for more equitable and just societies, there existed, and continue to exist, persistent colonial social and racial hierarchies in Latin America. Spanish and Portuguese colonization of the Americas (c. 1521–1821) had resulted in a stratified society that privileged those of European heritage. Indigenous, Black, and mixed race populations often occupied the lower strata of society. In a variety of mediums and styles, artists sought to expose the rampant social and racial inequities that existed in their countries, cities, and communities.

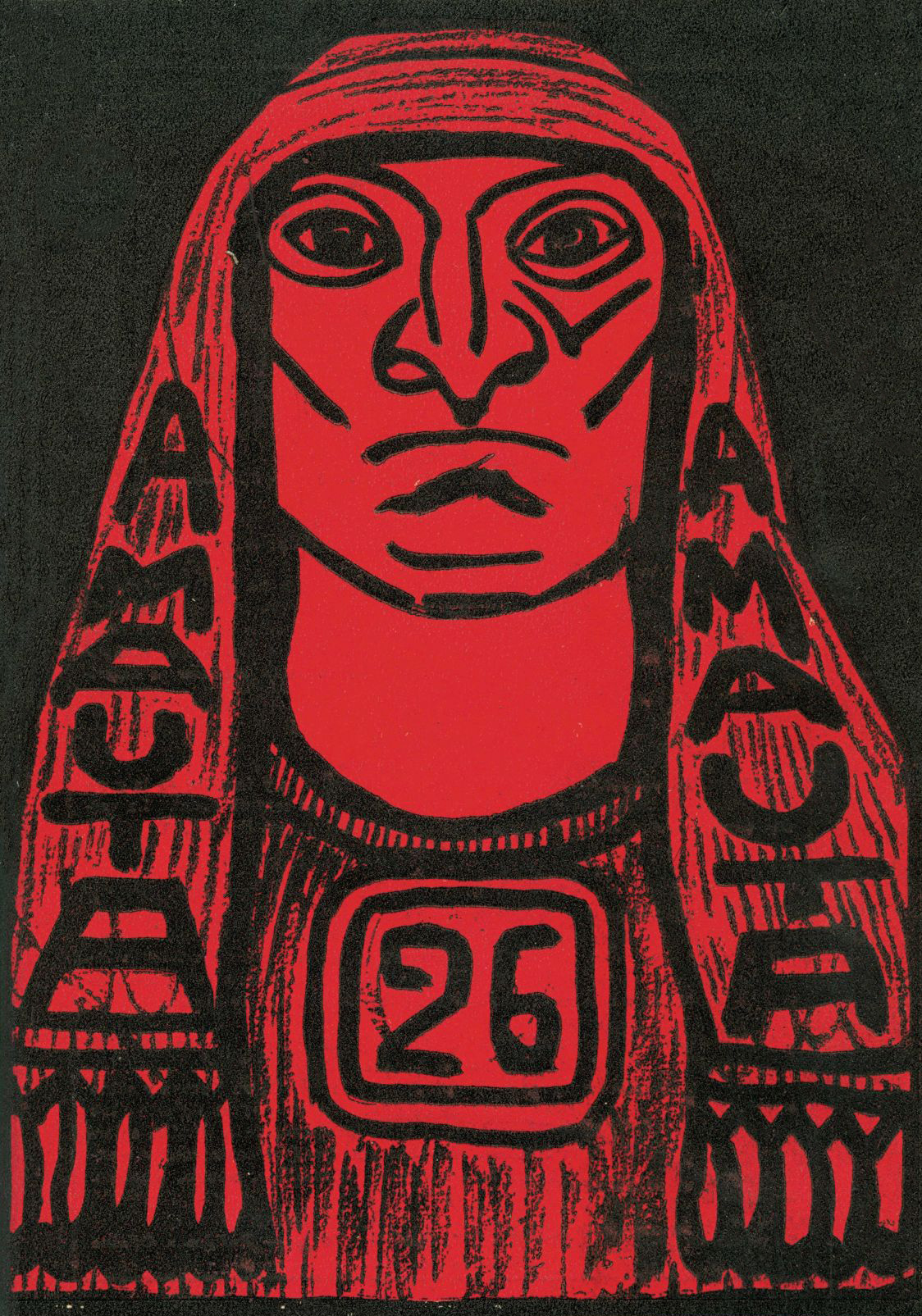

Latin American artists were influenced by the writings of José Carlos Mariátegui, who coined the term “indigenismo” and who had founded the influential journal Amauta (Quechua for “wise man”) in 1926. The cover of Amauta included an Amerindian man with a determined and proud gaze, conveying a sense of pride in Latin America’s native heritage and culture. Amauta not only featured the work of Martín Chambi, but also Diego Rivera (from Mexico) among others around Latin America. José Sabogal, cover of Amauta, number 26, 1929

Social Realism describes a style of representational art that focuses on depicting social, gender, and racial lived experiences. Wanting to give voice to the oppressed Indian and to denounce racist hierarchies, some artists championed indigenismo, a movement that focused on representing the experiences and plight of the marginalized Indigenous population. Although, it should be noted that in the portrayal of Indigenous people by non-Indigenous artists, indigenismo as a pictorial strategy was not without its biases. Artists like Diego Rivera, while celebrating Indigenous traditions, also created picturesque, idealized representations of the lower, working classes.

Watch a video and read essays about social realities and everyday life

Diego Rivera, Calla Lilly Vendor (Vendedora de Alcatraces): Rivera celebrates Indigenous culture, but also points to poverty in this melancholy painting of a flower seller.

Read Now >

Martín Chambi, Juan de la Cruz Sihuana, Cuzco Studio: This photograph of Sihuana is a complex portrait of an Indigenous Peruvian man in traditional dress.

Read Now >

Marc Ferrez, Slaves at a Coffee Yard in a Farm, Vale do Paraiba, São Paulo: Ferrez intentionally concealed the brutal and inhumane conditions of slavery in Brazil in his photograph.

Read Now >/3 Completed

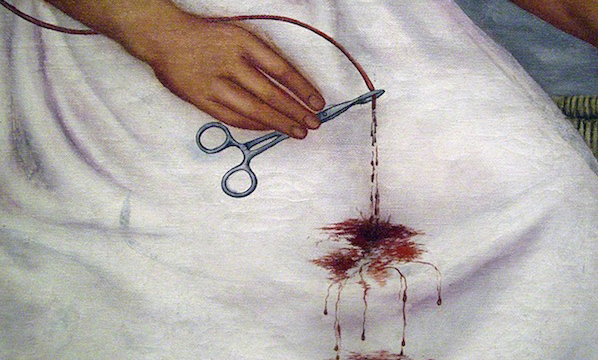

Exploring the Personal and the Unconscious

Not all Latin American artists embraced the monumental public art of muralism or the socio-political bent of indigenismo. Some Latin American artists rejected forthright political subjects in favor of exploring the freedom of the imagination and the creative potential of the unconscious mind. These artists were drawn to Surrealism and the tenets laid forth by its founder, the French writer André Breton, but these ties tended to be loose. Several artists rejected the Surrealist label, perhaps most famous among them, Frida Kahlo. Yet many artists shared Surrealist objectives such as embracing chance and rejecting rational thought to achieve more authentic ideas and expression. These artists were drawn to psychoanalysis, a psychological therapy that treats mental disorders by examining conscious and unconscious states of mind, using dream interpretation and other methods.

Wifredo Lam, The Jungle, 1942–43, gouache on paper mounted on canvas, 239.4 x 229.9 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

Many Latin American artists associated with Surrealism employed artistic techniques that could express the subconscious, such as automatic drawing where the artist draws at random without preconceived thought. Some Latin American artists also valued local myths and rituals, Indigenous cosmologies, and magical realism.

Frida Kahlo, My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree), 1936, oil and tempera on zinc, 30.7 x 34.5 cm (Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico City)

As in Europe, women artists formed a key component of this group of artists, finding the explorations of their inner minds and personal experiences more meaningful than large-scale historical narratives. Artists also portrayed the multiculturalism prevalent in Latin America, where many diverse peoples, including Indigenous, African, European, and Asian, intermixed.

Read essays and watch videos about the personal and the unconscious

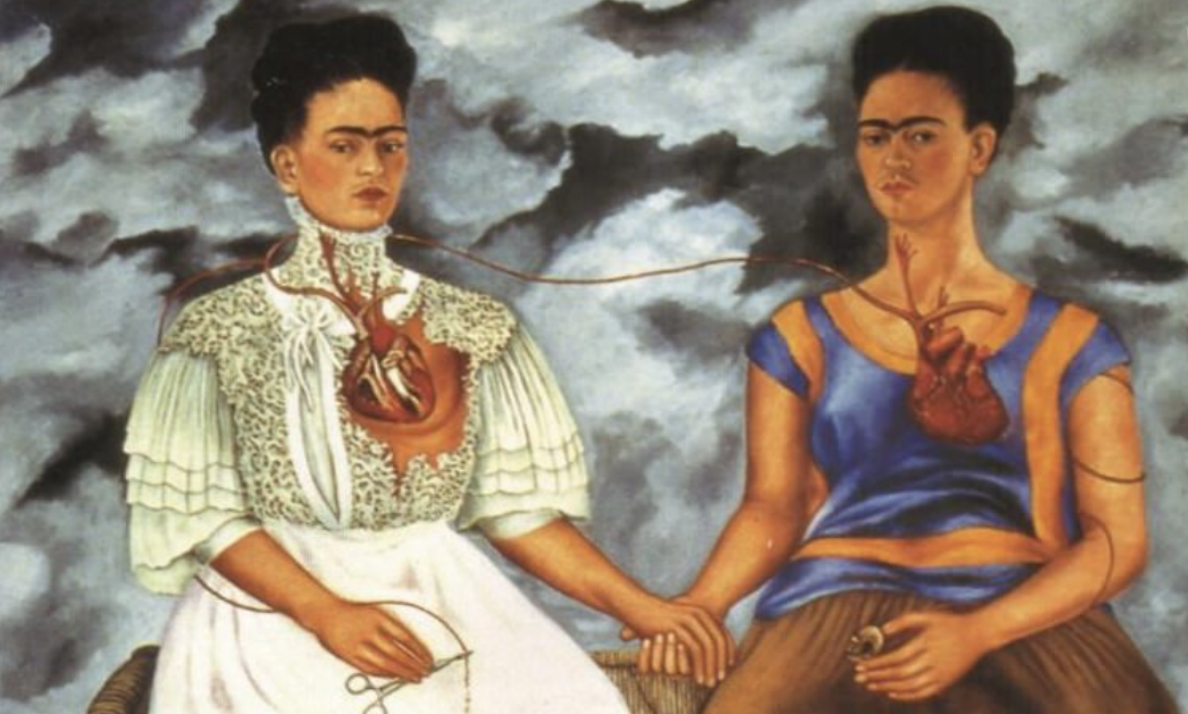

Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas): The Fridas are identical twins except in their attire, a poignant issue for Kahlo at this moment.

Read Now >

Wifredo Lam, The Jungle: Lam created a new narrative within the Cuban imagination, one rooted in the island’s complex history.

Read Now >

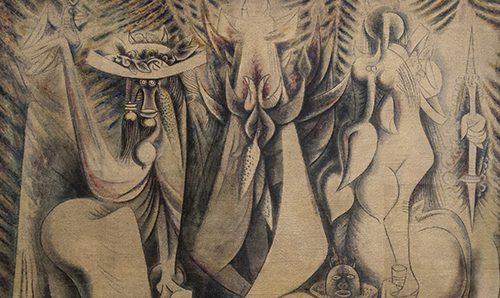

Wifredo Lam, The Eternal Presence (An Homage to Alejandro García Caturia): Lam merged Afro-Cuban Santería, the tropical vegetation of his native land, the Chinese philosophies of the Yin, Yang, and Tao doctrine, and alchemical teachings into his visual representations.

Read Now >/5 Completed

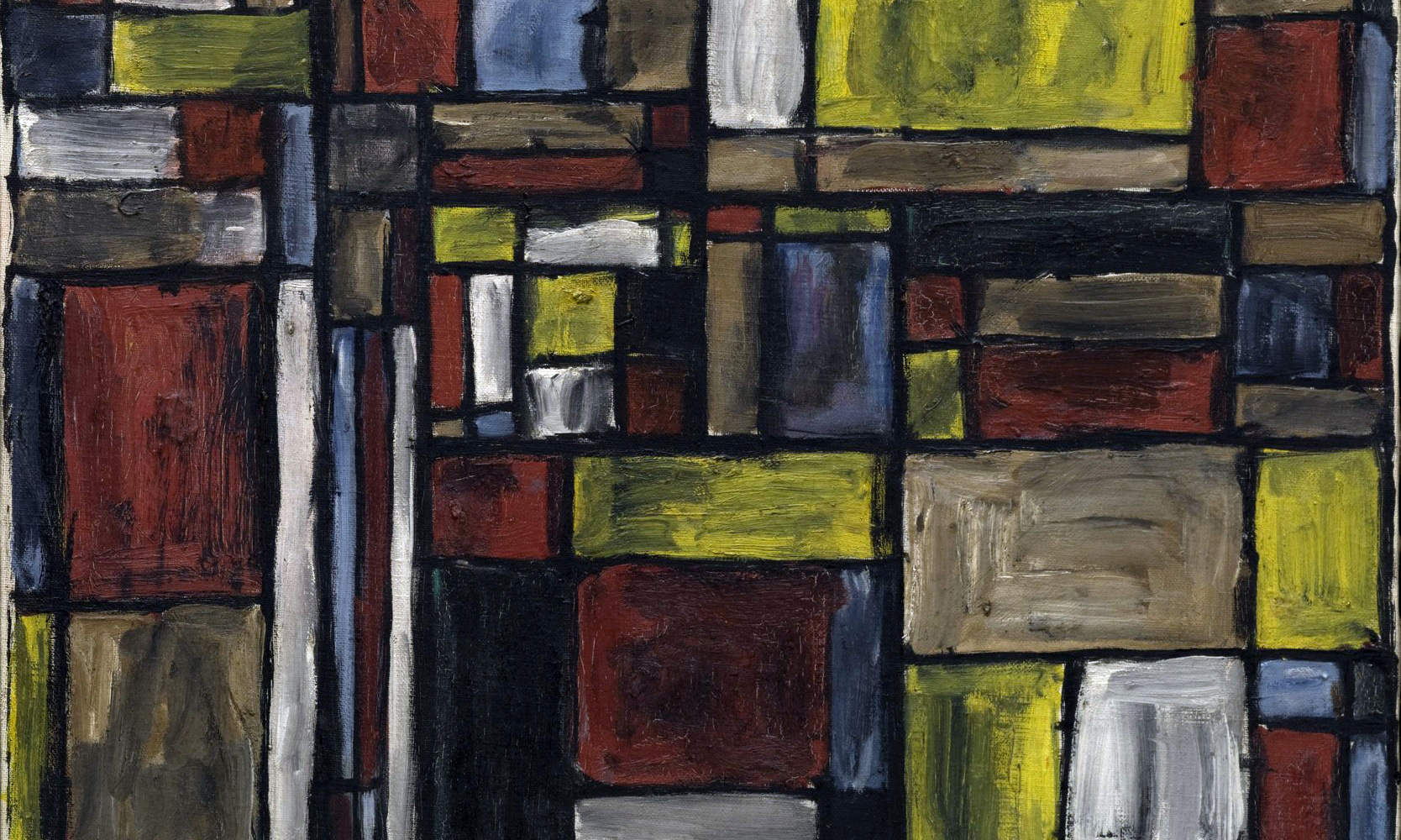

Crossing the Line: Geometric Abstraction

In the 1930s onward, many artists from Latin America were drawn to abstraction. Geometry held special appeal as both subject and form because it not only reflected the increasing urbanization and industrialization of the region, but it also related to pictorial symbols associated with pre-Hispanic cultures, particularly from the Andean region.

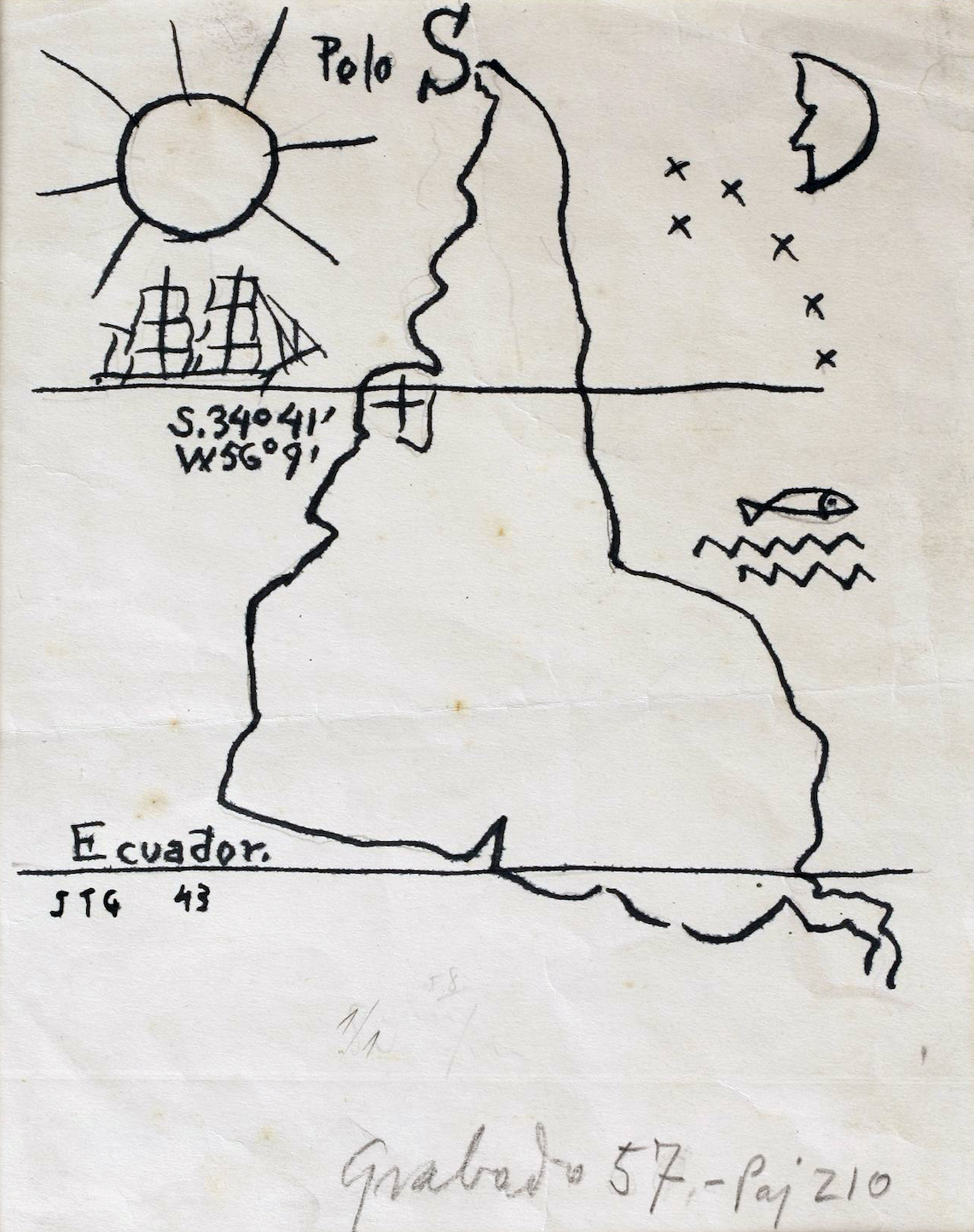

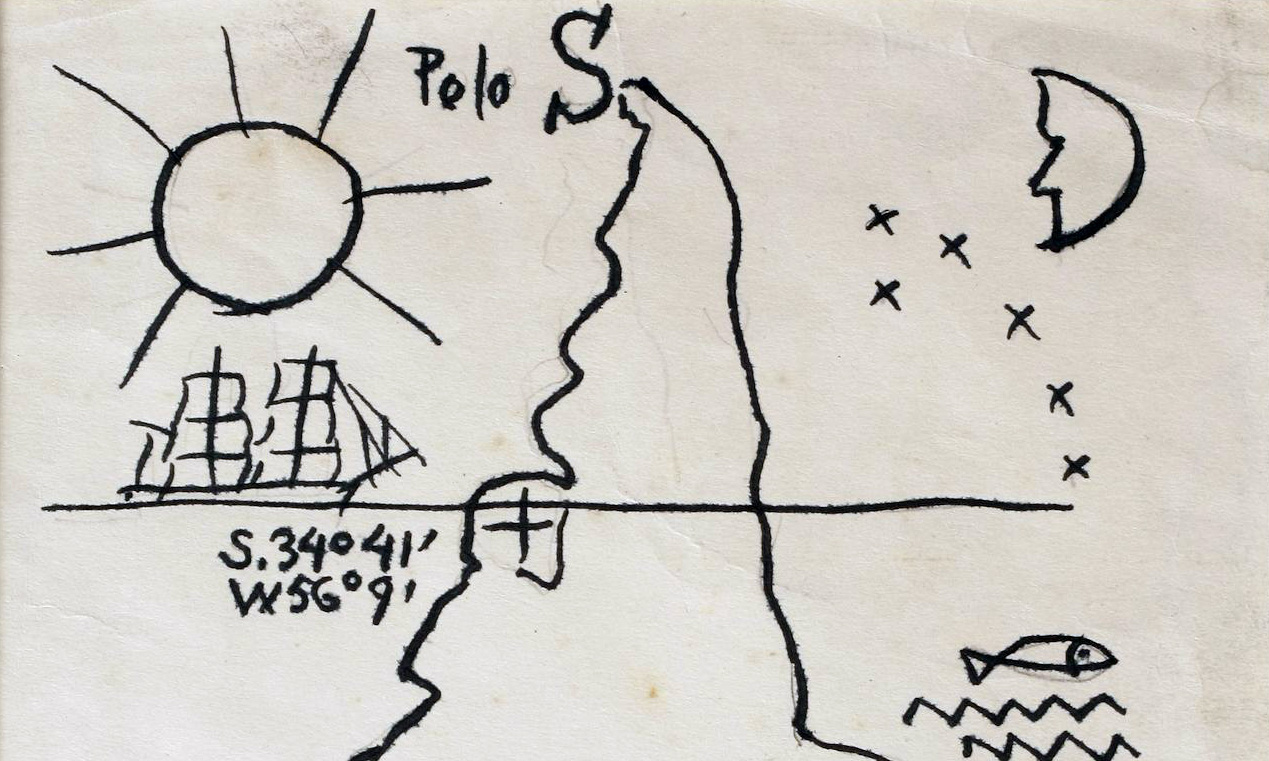

Joaquín Torres-García, América Invertida (Inverted America), 1943, ink on paper, 22 x 16 cm (Fundación Torres García, Montevideo)

Geometric Abstraction, which used elemental geometric shapes to create a pictorial reality, took many forms in different parts of Latin America. In the 1930s, the Uruguayan artist Joaquín Torres-García created his own pictographic, abstract style, known as Constructive Universalism. During the 1940s, Argentinian artists favored an abstract art that was not based on observed reality, known as Concrete Art. These Argentine artists began to experiment with irregular, broken frames and viewer manipulation of the artwork.

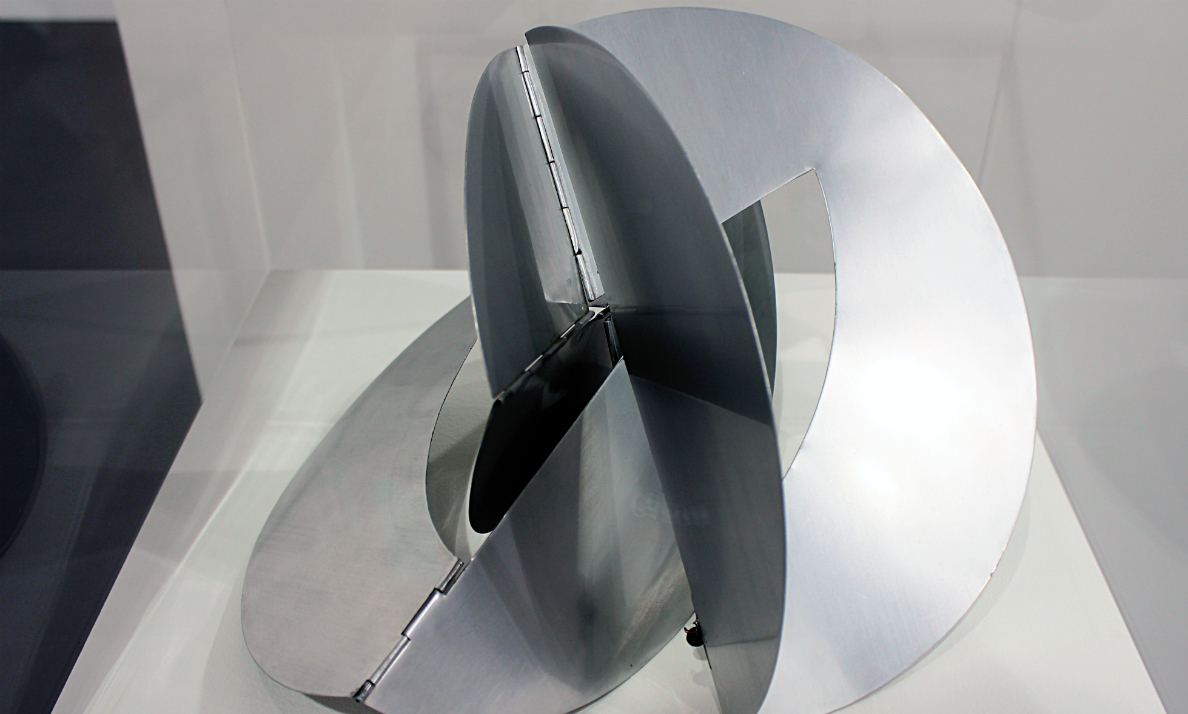

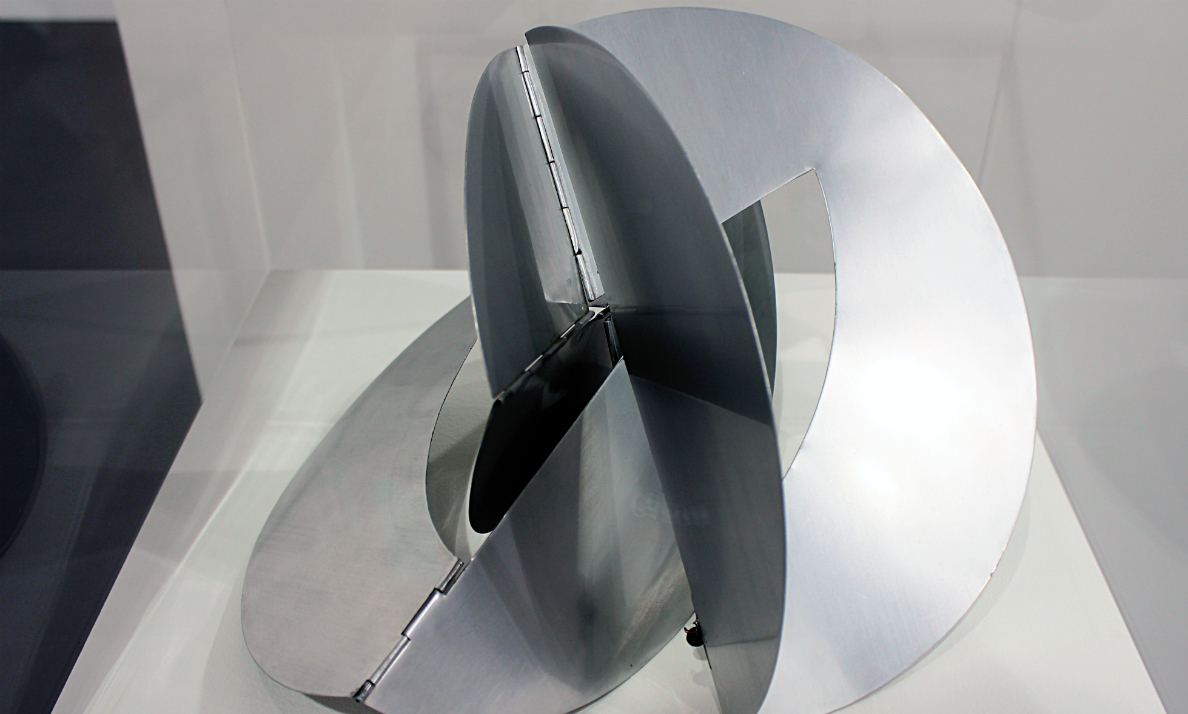

Lygia Clark, Bicho, 1962, aluminum (photo: trevor.patt, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Concrete Art also developed in Brazil where artists forged links between art, industry, and technology. In 1950s Venezuela, artists developed Optical and Kinetic art, manipulating space, light, line, color, and form to create motion or the illusion of movement. They used mixed media and also valued viewer participation, advocating for a more interactive art experience. In Brazil in the 1960s–80s, Neo-Concrete artists moved away from the scientific rationalist approach of the Concrete Art movement, and instead, favored a return to organic shapes, color, and light to encourage sensual, emotional connections to art.

Read essays about geometric abstraction

Joaquín Torres-García, Inverted America: Torres-García upended traditional hierarchical structures by defining the art of South America on its own terms, rather than in relation to that of the North (i.e. the United States and Europe).

Read Now >

Lygia Clark, Bicho: The viewer can fold, turn, close, and open Bicho, exploring its multifaceted nature.

Read Now >/3 Completed

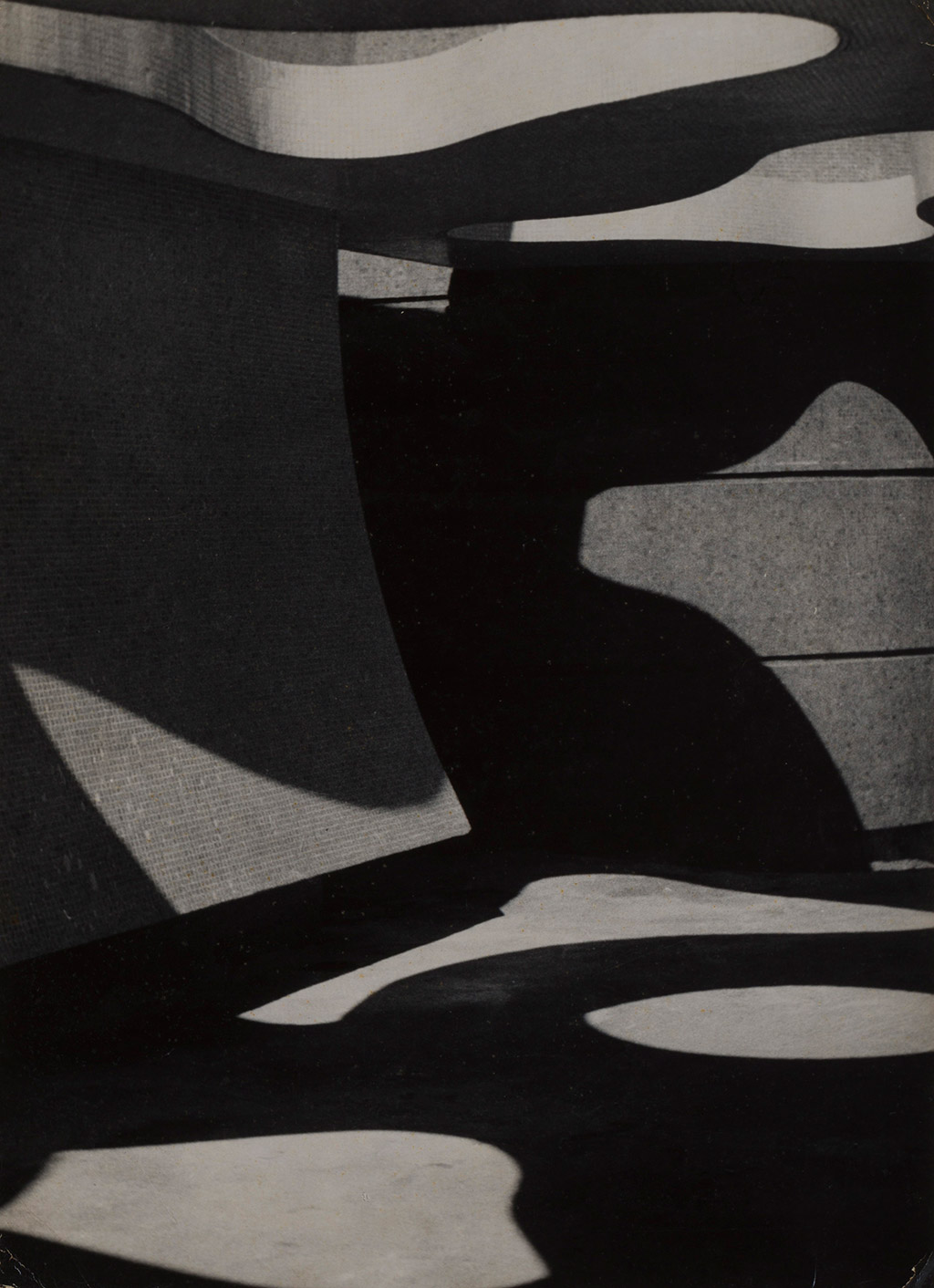

Transforming Spaces

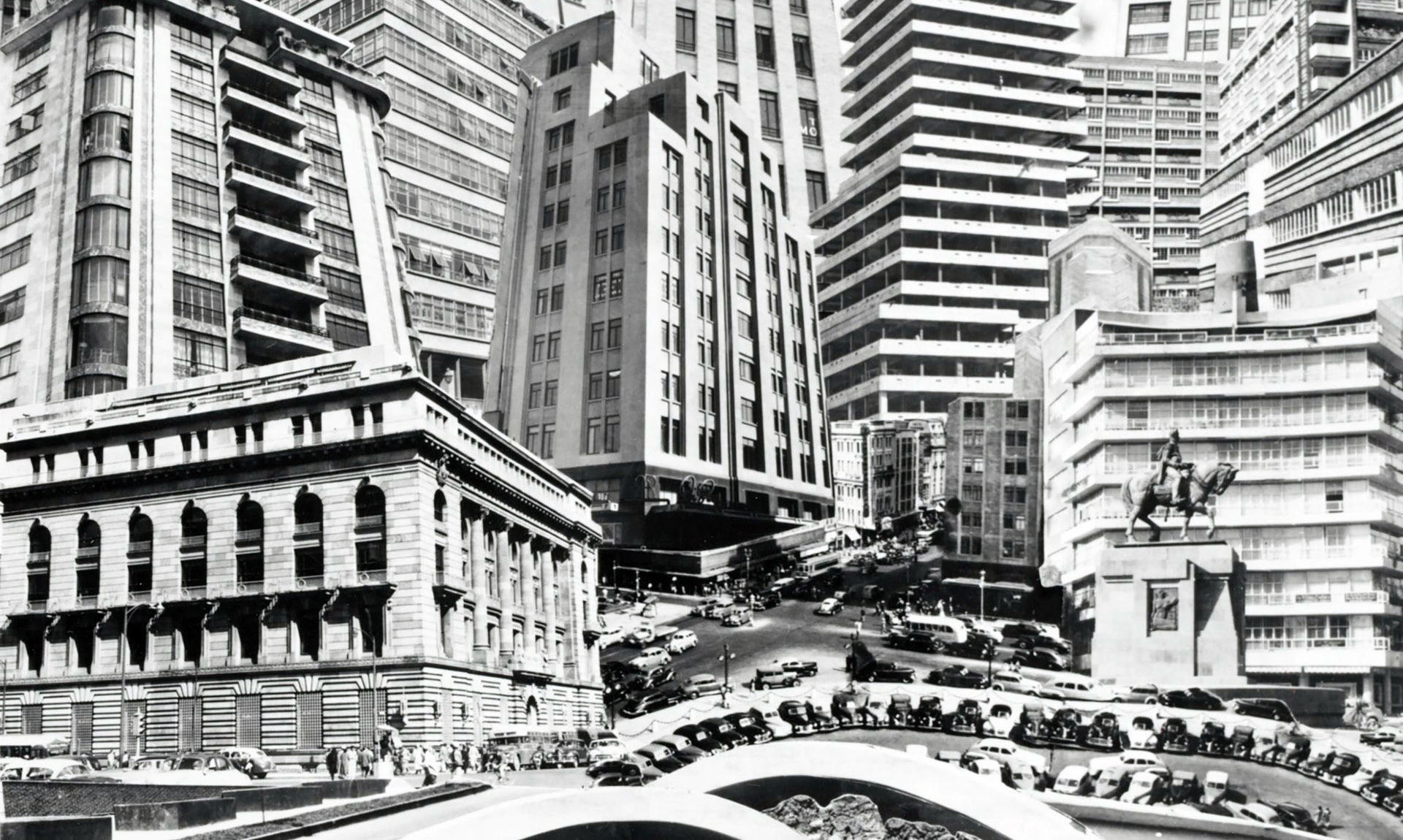

Public spaces also underwent a modernization that transformed urban centers into modern metropolises. Modern architecture in Latin America, such as the International Style, shared affinities with Geometric Abstraction in that both favored functionality, geometric designs, modular units, and clean lines. Photography became an ideal medium with which to capture the radical transformations of Latin American cities, and the tensions between a traditional past and a modern future.

Read essays about transforming spaces

International Style architecture in Mexico and Brazil: The International Style of architecture flourished in the mid-twentieth century, replacing the classicism of the previous decades.

Read Now >

José Yalenti, Architecture or Twilight: Recognizing the photograph’s subject allows us to see how the picture engages two important media that were intertwined in 1950s Brazil: architecture and photography.

Read Now >

Lola Álvarez Bravo, Architectural Anarchy in Mexico City: Mexican photographer Lola Álvarez Bravo thought architecture could be subversive and revolutionary.

Read Now >/3 Completed

As seen in this chapter, Latin American Modern Art is diverse and varied. No one style or artist can capture the tremendous range of art produced during this period. From bold, expressionistic paintings of violence and war and monumental murals of the social and racial inequities caused by colonization, to geometric abstractions devoid of subject matter and photographs of the industrialization of rapidly changing cities, artists sought to represent what they encountered and experienced in their everyday, modern lives.

Key questions to guide your reading

What is modernism? What characterizes Latin American Modern Art?

What is the relationship between Latin American Modernism and Modernism in Europe, the U.S., and elsewhere?

How does Latin American Modern Art take shape and develop among different countries and regions?

Jump down to Terms to KnowWhat is modernism? What characterizes Latin American Modern Art?

What is the relationship between Latin American Modernism and Modernism in Europe, the U.S., and elsewhere?

How does Latin American Modern Art take shape and develop among different countries and regions?

Jump down to Terms to KnowTerms to know and use

Abstraction

Concrete Art

Indigenismo

Mexicanidad

Mexican muralists

Mexican Revolution

Modernism

Mural

Social Realism

Surrealism