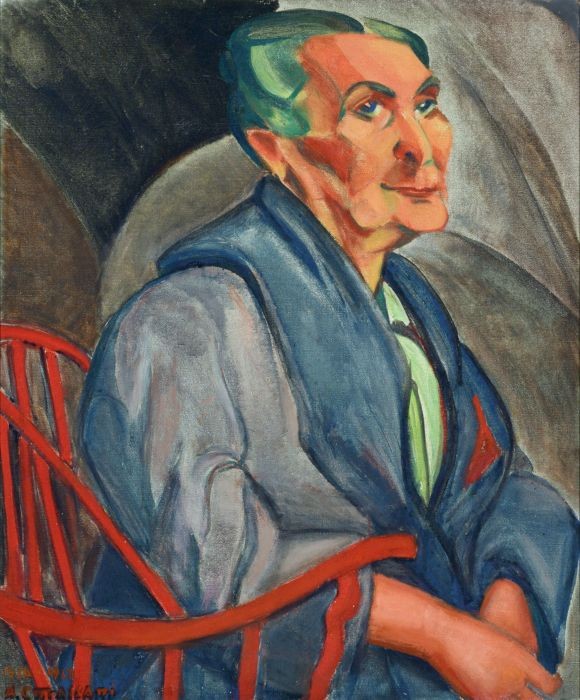

Anita Malfatti, The Fool, 1913, oil on canvas, 61 cm x 50.6 cm (Museum of Contemporary Art of University of São Paulo, Brazil)

Modern art in São Paulo

1922 was an important year for avant-garde activities in Brazil. During the week of February 11–18, which was also Carnival and the centennial celebration of Brazil’s declaration of independence from Portugal, a multidisciplinary event, known as Semana de Arte Moderna (Modern Art Week) took place at the Municipal Theatre of São Paulo. It featured an art exhibition, poetry readings, music, and dance festivals organized by the painter Emiliano di Cavalcanti, and poets Oswald de Andrade and Mario de Andrade (no relation to Oswald).

Municipal Theatre of São Paulo, 1903–11, São Paulo, Brazil (photo taken during the 1920s, Brazilian National Archives)

Victor Brecheret, Eve, 1921 (photo: Pinheiro Natália, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Modern Art Week was intended to announce the São Paulo avant-garde’s break with earlier art. The exhibition of art included works by the sculptor Victor Brecheret, who returned to Brazil from Rome in 1919, paintings by Anita Malfatti, completed during her time in Berlin and New York, and di Cavalcanti, along with numerous other painters, sculptors, and architects. One of the other painters who would play a significant role in the development of Brazilian modernism was Tarsila do Amaral.

The Semana was conceived as a reaction against the official academic art and literature. Academic art was associated with the conservative oligarchy (powerful families who owned huge coffee plantations) and remained intent on emulating the time-worn Romanticism of nineteenth-century Europe. In many respects the impetus for the art exhibition was the radical newness of Brecheret’s sculptures and Malfatti’s expressionist paintings. Brecheret’s sculptures were rendered in a dramatically stylized, proto-Art Deco style, and Malfatti’s paintings were met with derision from the establishment when first exhibited in 1917.

At the time of the Semana, São Paulo was one of the fastest growing cities in Brazil. Industrialization was transforming this coffee-growing center into a thriving metropolis with electrified street lamps, a café culture, movie theaters, and luxurious department stores. Young Brazilian intellectuals were hungry for art and literature that matched the city’s vibrant energy and they were also part of a political movement intent on challenging the stranglehold of the oligarchy. Like their peers in Argentina, writers and artists like Mario and Oswald de Andrade and di Cavalcanti were eager for an intellectual culture that was not only modern and up-to-date but also intrinsically Brazilian.

The controversy surrounding Malfatti’s paintings

Anita Malfatti, The Fool, 1913, oil on canvas, 61 cm x 50.6 cm (Museum of Contemporary Art of University of São Paulo, Brazil)

When Malfatti exhibited a selection of her paintings, including The Fool and The Man of Seven Colors, the art critic Monteiro Lobato attacked her in an influential São Paulo newspaper (“A Propósito da Exposição”). He described her painting as “beastly” and “deformed,” the latter a satirical play on the translation of her Italian last name (“mal fatti”); he declared her painting to be akin to art produced by the mentally insane, work born of “paranoia and mystification,” and finally he dismissed her as “a girl who paints.”

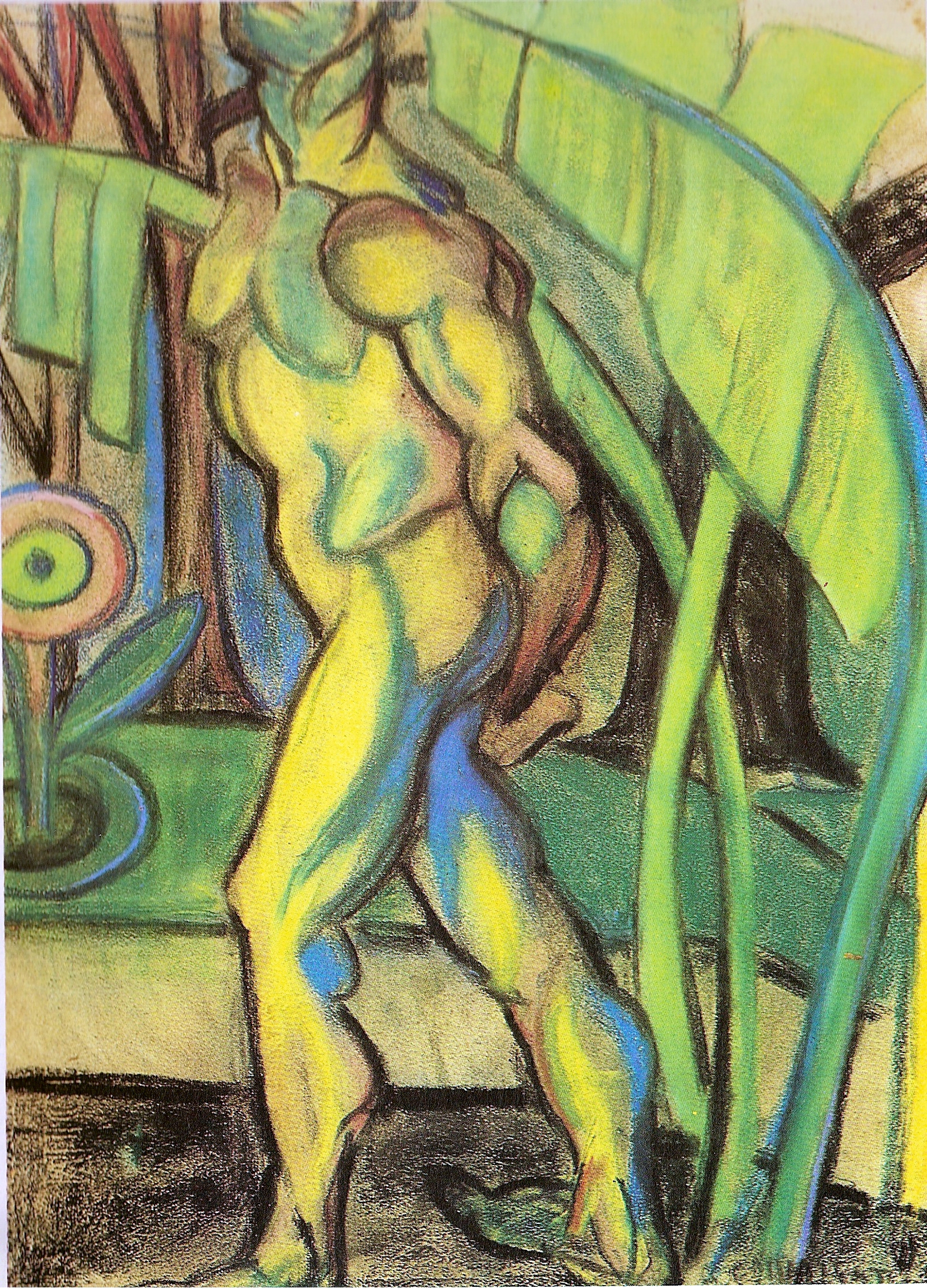

Anita Malfatti, The Man of Seven Colors, 1915–16, charcoal and pastel on paper, 62 x 46 cm (Museu de Arte Brasileira, São Paulo)

Describing her as an amateurish follower of the “excesses” of Picasso, Lobato described two kinds of artists, those who see things “normally,” in the tradition of Praxiteles, Raphael, Rubens, and Rodin, and feel called to preserve the rhythm of life aesthetically, and, those who see things as “deformed” and “sadistic.” He wrote that such artists, Malfatti among them, were merely “shooting stars” destined to oblivion. Lobato was surely offended both by her expressionistic and non-naturalistic use of color but also by her engagement with the male nude, which was still taboo for women artists.

Malfatti’s approach was, however, entirely in keeping with modern art in Berlin and New York where she had studied with Lovis Corinth and Homer Boss. It was Boss who had challenged her to use pure color, as seen in the high key yellow, green, and blue in both The Fool and The Man of Seven Colors.

In Man of Seven Colors she used expressive lines to emphasize the sculptural quality of the nude body and areas of pure color to emphasize figural torsion. The fact that the nude is headless suggests a distancing from the individual portrayed, and the potential erotic charge. The painting engages the viewer more emotionally and cerebrally than sexually, given the model’s modest posture.

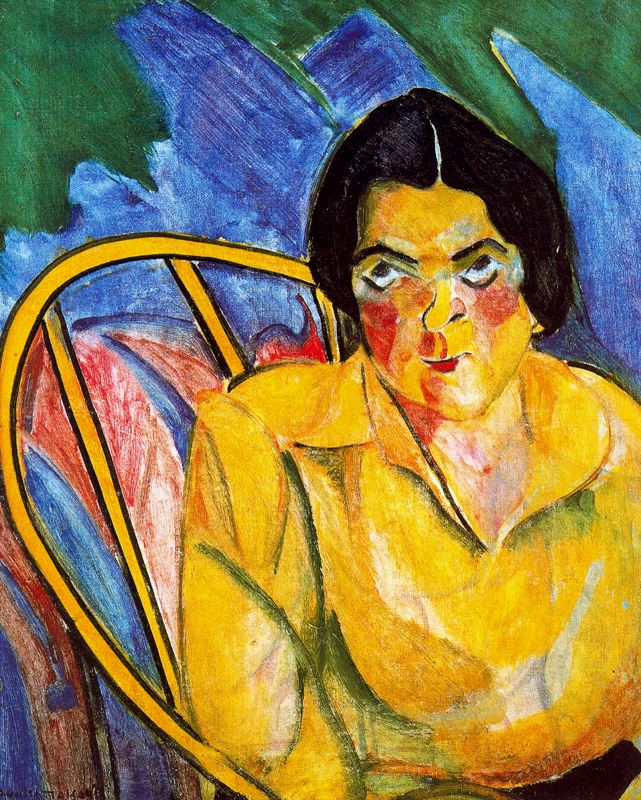

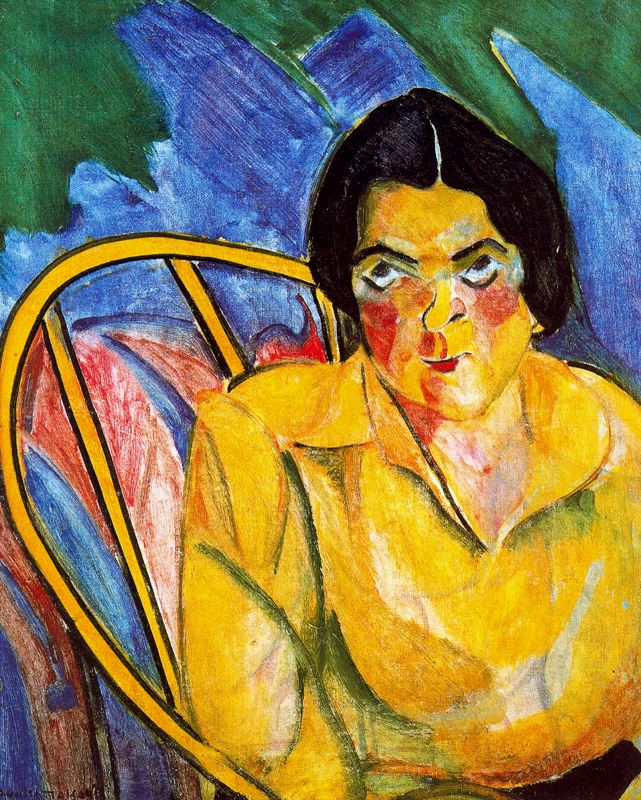

Anita Malfatti and modern art in Brazil

In the wake of the controversy surrounding the exhibition of Anita Malfatti’s work, young writers like Mario de Andrade rallied to her side, championing her for initiating modern art in Brazil. Twenty of her paintings were included in the exhibition during the Semana, including works like The Yellow Man and Woman with Green Hair, the titles of which call attention to the innovative use of color that had so incensed Monteiro Lobato. Emiliano di Cavalcanti recalled that Malfatti’s exhibition was “a revelation . . . [she] came from the outside, and her modernism . . . had the seal of experience in Paris, Rome, and Berlin.” [1]

Emiliano Di Cavalcanti

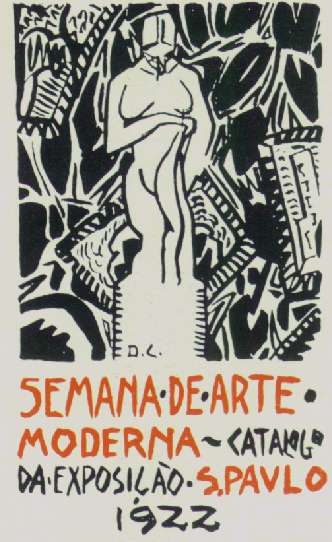

Di Cavalcanti worked as an illustrator for newspapers and magazines. He designed the program for the Semana de Arte Moderna, and his image for the cover declares his embrace of modern art and of stylistic diversity. It features a female nude standing on a pedestal, but the figure is rendered with a combination of sharp and sensual curving lines, not unlike Malfatti’s work and even Picasso’s already infamous Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1906–07).

Emiliano di Cavalcanti, Semana de Arte Moderna, 1922

Di Cavalcanti invokes the turn in avant-garde art toward primitivism, whereby artists like Pablo Picasso and the Emil Nolde drew inspiration from objects appropriated from Indigenous peoples and cultures in Africa and the South Pacific, as well as pre-conquest civilizations of the Americas to challenge establishment values by engaging in formal and conceptual experiments inspired by the exotic “other.” Throughout Latin America primitivism was made even more complex as many artists were rediscovering “other” cultures within their own local contexts and appropriating these in order to innovate and at times challenge European domination of the arts and remnants of colonial practices.

Here, di Cavalcanti sets the nude amidst a primitivistic background of foliage. In the lower right, a simplified human figure recalls a trope of ethnographic sculpture. In the middle- and background there appear to be modernist, even Cubist paintings hung askew. Their frames are articulated with jagged lines that lend additional energy to the composition.

Despite being a leading figure in the emergence of Brazilian modernism, di Cavalcanti’s own style was still overtly sensual. His portraits and figural compositions aimed at championing “another concept of femininity” as representative of the authentic Brazil, or brasilidade, and in this regard his work was somewhat atypical of the art movement launched by the Semana de Arte Moderna. [2]

In a context dominated by the white elite, di Cavalcanti’s pictorial interpretations of Brazil’s working classes need to be understood as a confrontation of prevailing notions of beauty. They are also in dialogue with Mexican muralists who wanted to focus on the working class and make art for the people. To the modern eye however, his work appears to internalize stereotypes of Brazil’s exotic “other” even if his aim was to subvert academic authority by affirming the beauty and value of Brazil’s mixed-race working class.

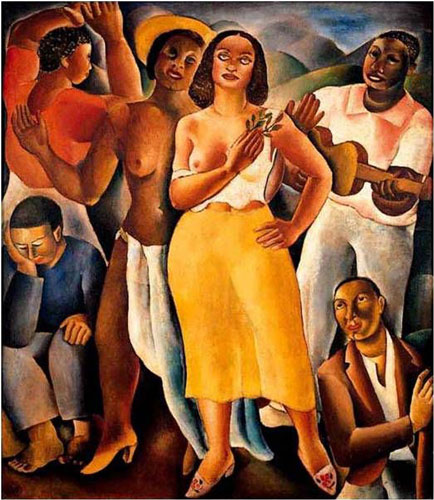

Emiliano di Cavalcanti, Samba, 1925, oil on canvas, 175 x 154 cm (Collection of Genviève and Jean Boghici, Rio de Janeiro)

Di Cavalcanti’s approach is exemplified in Samba, a painting completed in 1925 following a two-year sojourn in Paris where he met Picasso. The painting depicts a partly nude Black woman and a partially clothed mulatta swaying to the music of a guitar, strummed by a young Black man. The figures’ vacant stares serve to heighten the quality of sensual abandon. Art historian Edith Wolfe has observed that the solid, naturalistic bodies suggest an affinity for Picasso’s post-Cubist classicism transferred to the favela in the service of nationalistic modernism. [3]

Di Cavalcanti’s primitivized bodies seem to risk re-colonizing Brazil’s marginal communities, especially its women, in the service of the male gaze. Others have argued that the artist’s aim was to extoll Brazilian unity by celebrating and reconciling racial and class disparities. Di Cavalcanti’s Samba exemplifies the quest for an art that was both modern and Brazilian, and that followed in the wake of the Semana de Arte Moderna.

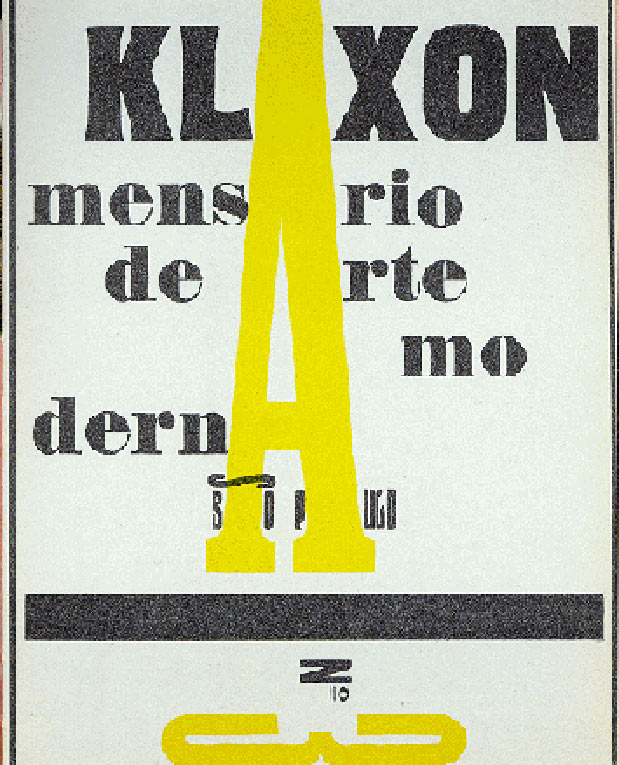

Building from the Semana de Arte Moderna, artists and writers went on to champion modernism in the pages of the journal Klaxon, considered the first publication of the Brazilian avant-garde and published between 1922 and 1923. By 1923, however, not only di Cavalcanti, but also Malfatti, Brecheret, Oswald de Andrade, and Vicente do Rêgo Monteiro were all in Paris, where each in their own way engaged with the avant-garde in the pursuit of a Brazilian modernism.