Women as objects of fear and desire

Women were a central subject in Surrealist art. Male Surrealist artists often portrayed fragmented, deformed, and dismembered female bodies as objects of violent erotic imaginings. This may be attributed, at least in part, to the Surrealists’ engagement with Freudian psychoanalytic theories, in which the female body is both the primary object of male heterosexual desire and a source of great anxiety resulting from male fears of castration. Women thus represent the greatest source of erotic satisfaction, while also inspiring disgust and terror.

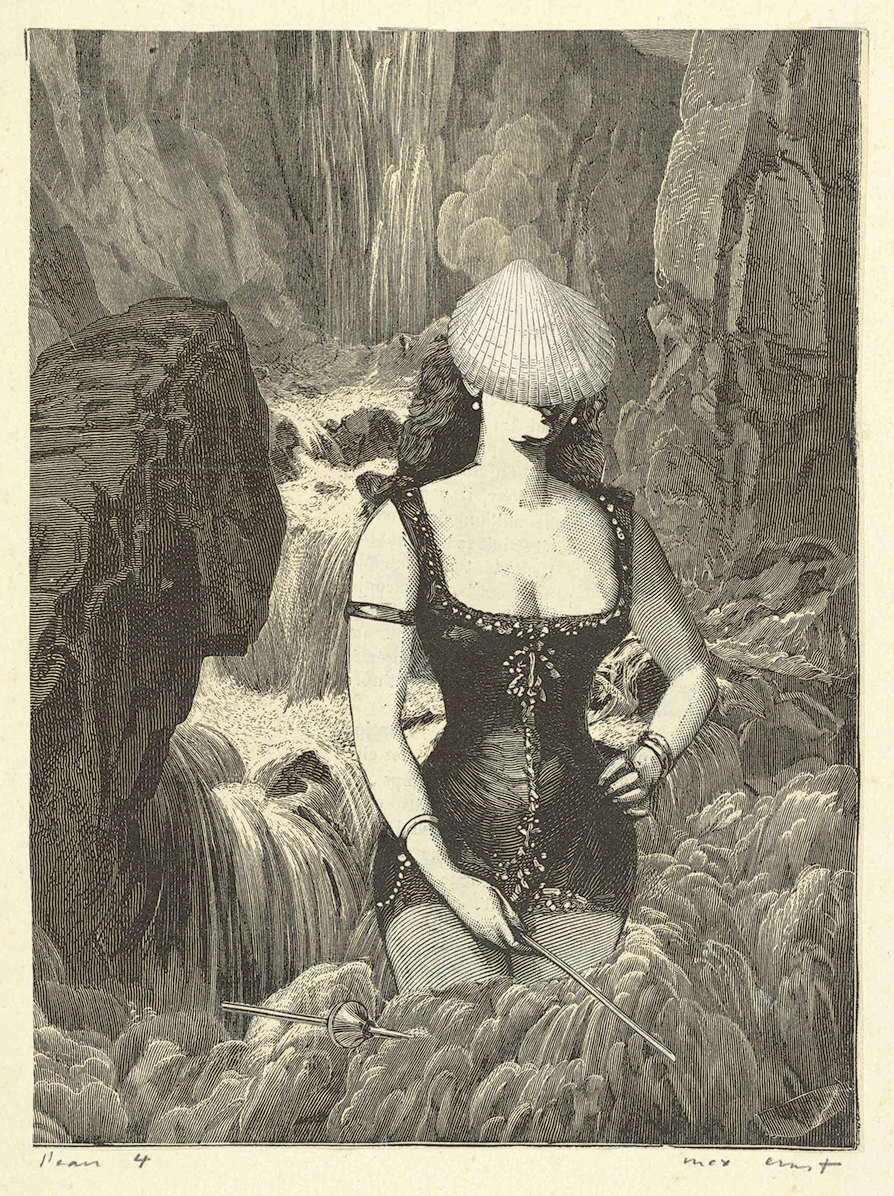

With her seemingly endless permutations and multiplication of body parts, Hans Bellmer’s fetishistic doll can be seen as an objectification of these powerful and contradictory emotions. The Surrealists’ perception of women as terrifying but erotic objects also appears in their fascination with the praying mantis. In the 1930s many Surrealist artists depicted this insect, whose female beheads and eats the male during or immediately following copulation. Max Ernst’s ironically titled The Joy of Life shows the insects in the foreground of an ominous jungle scene filled with half-hidden, menacing creatures.

Max Ernst, The Joy of Life, 1936, oil on canvas, 73.5 x 93 cm (Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art)

Women as a source of inspiration

The other side of the coin was a tendency to idealize women as beautiful, mysterious sources of inspiration. The violated and debased female body is such a commonplace of Surrealist art that it may seem surprising that the Surrealists were dedicated to romantic love. This is more evident in Surrealist writing than in the visual arts, but it was an attitude that affected the personal lives of artists and writers alike.

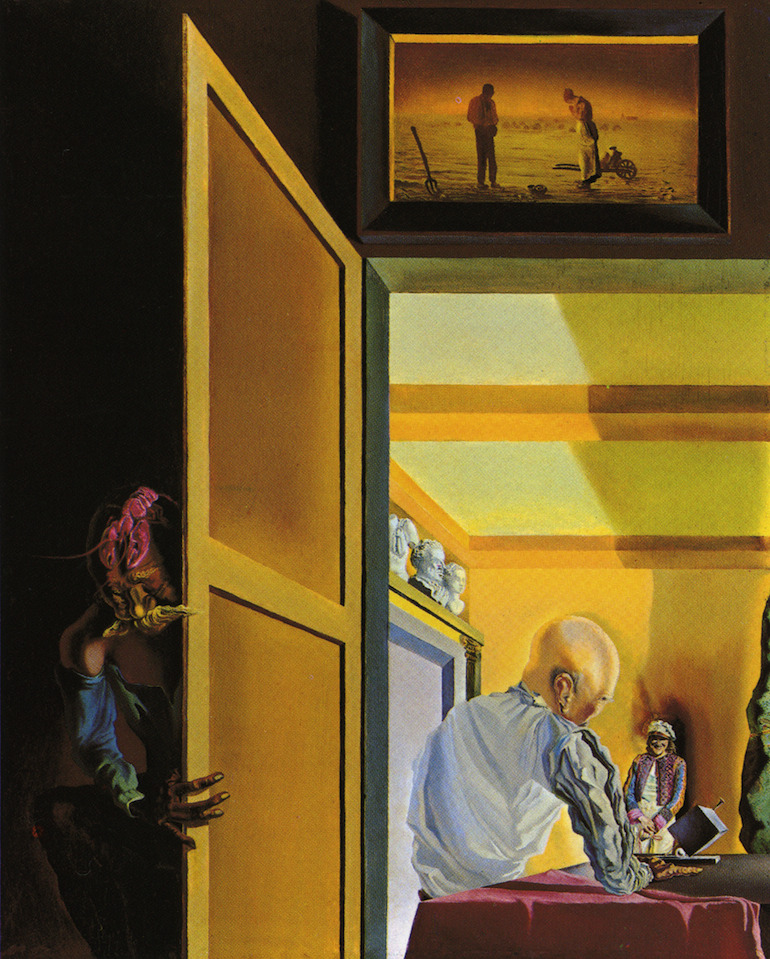

Man Ray photographed the Surrealist poet Paul Eluard’s second wife Nusch as the beloved muse to whom he dedicated many love poems. The wives and lovers of the male Surrealists were often key figures in the movement even if they were not themselves artists or writers. They were celebrated in Surrealist art and writings and often directly participated in the movement by signing manifestos, making objects, and contributing to exquisite corpses and other group activities. Gala Dalí was the most prominent. First the wife of the Surrealist poet Paul Eluard, then the lover of Max Ernst, she ultimately became the wife of Salvador Dalí, who dedicated all his work to her, even signing her name to his paintings because she inspired them.

Salvador Dalí, Gala and the Angelus of Millet before the arrival of the Conical Anamorphoses, 1933, oil on canvas, 24.2 x 19.2 cm (National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa)

Women Surrealist artists

In the early years of Surrealism no women artists were members of the group, but this changed over time as the movement grew in size and influence. Many of the most well-known women associated with Surrealism became involved with the movement through their personal relationships with Surrealist men. Meret Oppenheim and Lee Miller both worked with Man Ray, in addition to making their own Surrealist works. Leonora Carrington and Dorothea Tanning became involved with Surrealism through Max Ernst; Remedios Varo through the Surrealist poet Benjamin Péret; and Kay Sage through Yves Tanguy.

Kay Sage, A Finger on the Drum, 1940, oil on canvas, 15 x 21½ inches (National Gallery of Art, Washington)

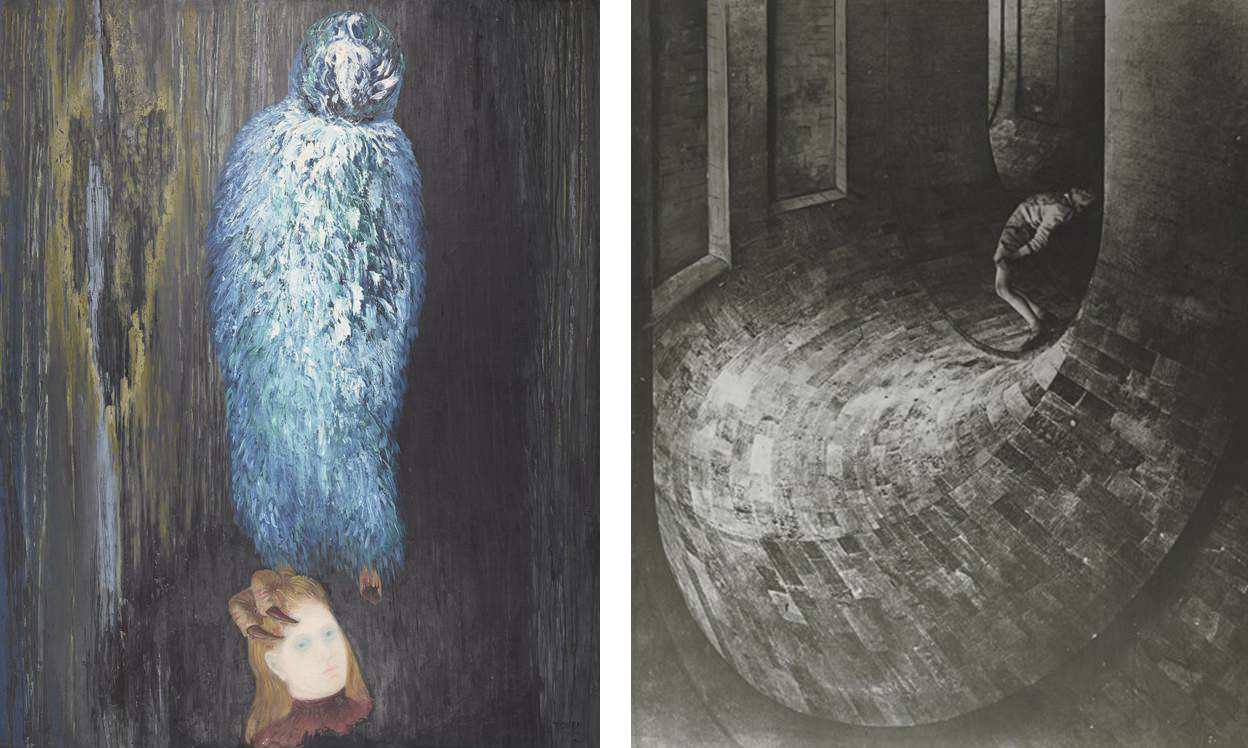

Leonor Fini exhibited with the Surrealists in the 1930s, as did the Czech Surrealist painter Toyen, and the photographers Claude Cahun and Dora Maar.

Left: Toyen (Maria Čerminová), The Message of the Forest, 1936, oil on canvas, 160 x 129 cm (National Galleries of Scotland); right: Dora Maar, Le Simulateur, 1936, gelatin silver print, 30.2 × 23.5 cm (The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)

Surrealist women representing women

Leonora Carrington, Self Portrait, c. 1938, oil on canvas, 25 5/8 x 32 inches (Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Given the Surrealist interest in creating art that manifested the unconscious and the prominence of Freudian themes in the work of male Surrealist artists, certain questions inevitably arise. How did female Surrealist artists represent their dreams and unconscious desires, and how are they different from the representations of male Surrealist artists? These are difficult questions to answer, in part because the Surrealists strongly rejected conformity. Although there are similarities between certain Surrealist artists, it is impossible to make sweeping generalizations about all male Surrealists, and this is equally true of the women.

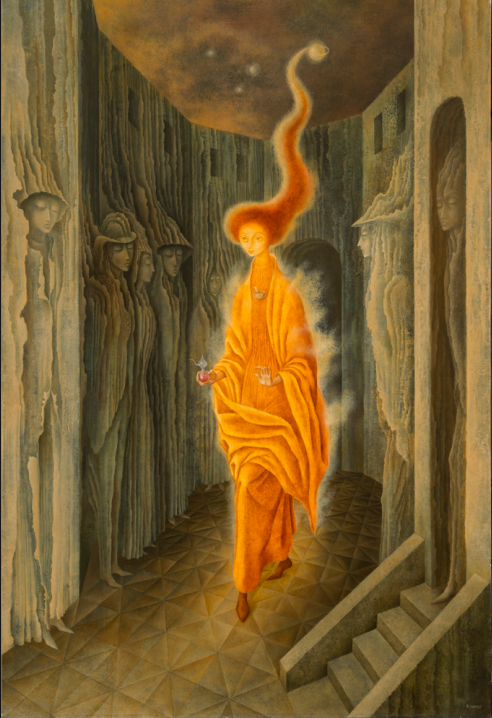

Many of the women associated with Surrealism were as interested in women as an artistic subject as the male Surrealists were. Their representations of women are, however, notably different. While male Surrealist artists often depicted faceless, distorted, and violated female bodies, artists such as Carrington, Varo, and Fini portrayed women, including themselves, as young and beautiful. In depictions of their dreams and in their self-representations, women artists associated with Surrealism often seem to conform to male Surrealist idealizations of women as beautiful, child-like creatures inhabiting magical dream environments.

Remedios Varo, The Call, 1961, oil on masonite, 39 ½ x 26 ¾ inches (National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC)

Women’s self-representations

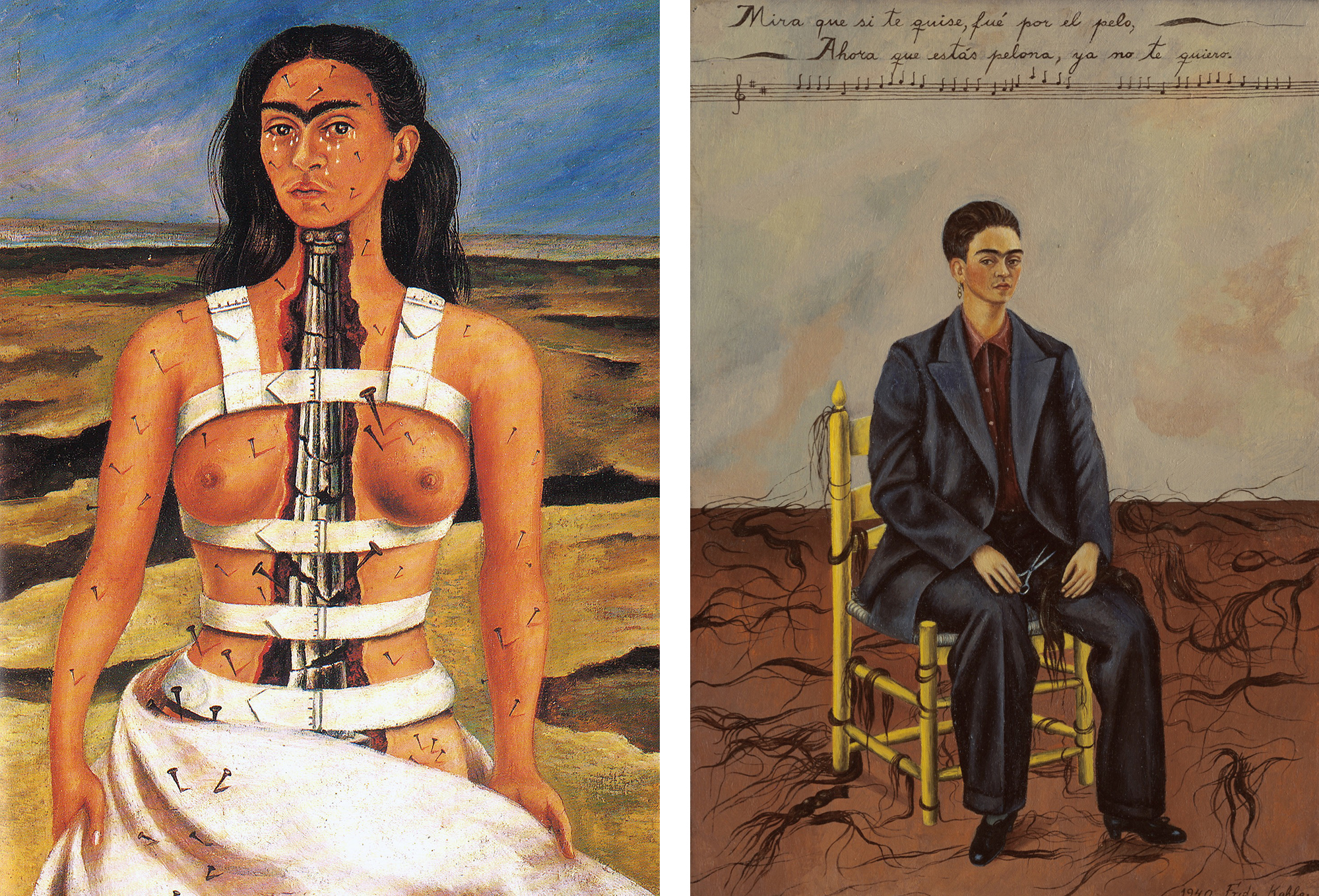

Left: Frida Kahlo, The Broken Column, 1944, oil on masonite, 30.5 x 39 cm (Museo Dolores Olmedo); Right: Frida Kahlo, Self Portrait with Cropped Hair, 1940, oil on canvas, 15 ¾ x 11 inches (MoMA)

Self-portraiture was a more significant genre among Surrealist women artists than it was among the men, and several women artists associated with the group are particularly notable for the depth and complexity of their engagement with self-representation. The most famous of these is Frida Kahlo, whom the Surrealist leader André Breton saluted as a natural Surrealist, although she never considered herself a member of the movement. Kahlo used her own image as a primary subject, often combining it with symbolic objects and scenes that represent her thoughts, feelings, and memories. She was also concerned with constructing her image in life, dressing in men’s clothes, or more often in traditional regional Mexican costumes, as a means of proclaiming her identity.

Leonor Fini, who also never joined the group but was friends with many Surrealists and participated in Surrealist exhibitions, was similarly preoccupied with her own image in art and life. She appears in her paintings as a beautiful, dominating, and sensual woman, often surrounded by imagined figures and environments. The self-image in her paintings was not unlike the figure she presented in person. She wore dramatic costumes, and once received the Surrealists dressed in priest’s robes, clothing she found particularly erotic and transgressive.

Unlike Kahlo and Fini, Claude Cahun participated in a variety of Surrealist group activities in the 1930s. In addition to making Surrealist objects, she produced a series of photographic self-portraits in which she transformed herself radically from one image to the next, appearing in several wearing masks and costumed as a doll. The gender ambiguities in many of her self-portraits suggest an exploration of her own image that is concerned with both personal and social issues of identity.

The role of women in Surrealism was complex and contradictory. The movement both infantilized and empowered women, treated them as erotic objects and supported their sexual emancipation, subjected them to the male gaze and validated their own self images. Furthermore, it is important to note that while women were a minority within the Surrealist group, many more women artists achieved significant recognition in the context of Surrealism than in other major modern art movements.

Additional resources:

Read a short biography of Toyen at the National Galleries of Scotland

Read more about Dora Maar at the Tate London

Read more about Dorothea Tanning and see more of her work at the Dorothea Tanning Foundation

Read more about Remedios Varo at MoMA

Read more about Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair at MoMA