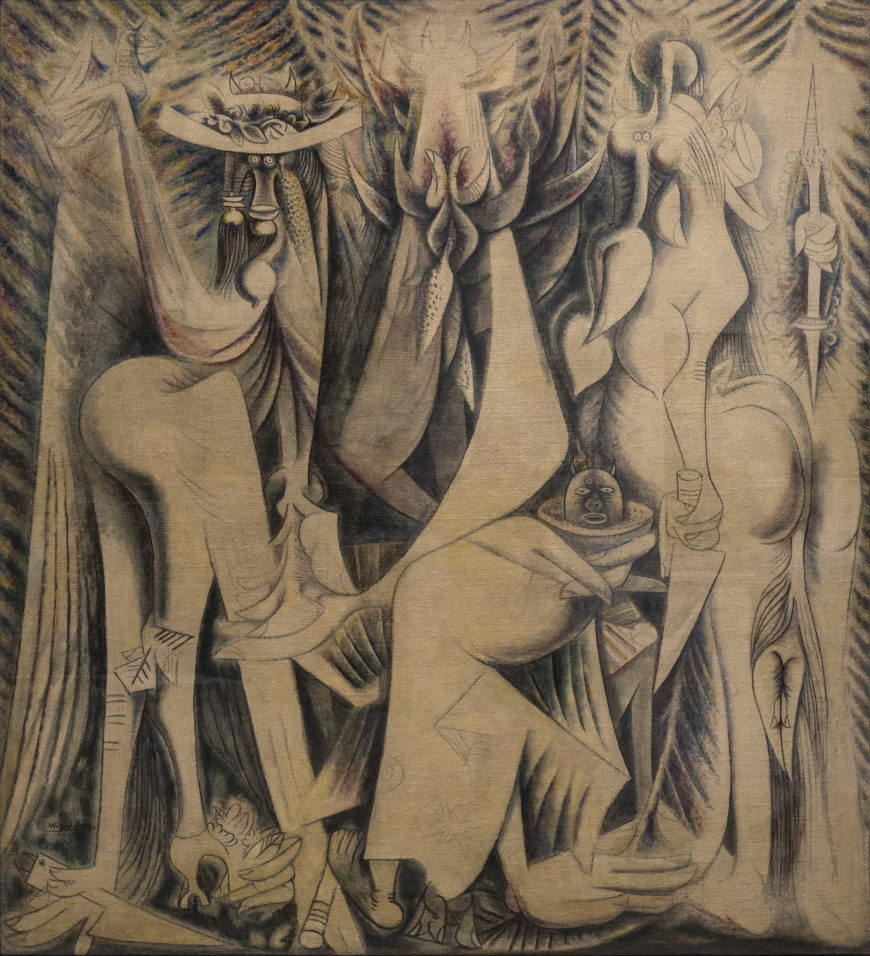

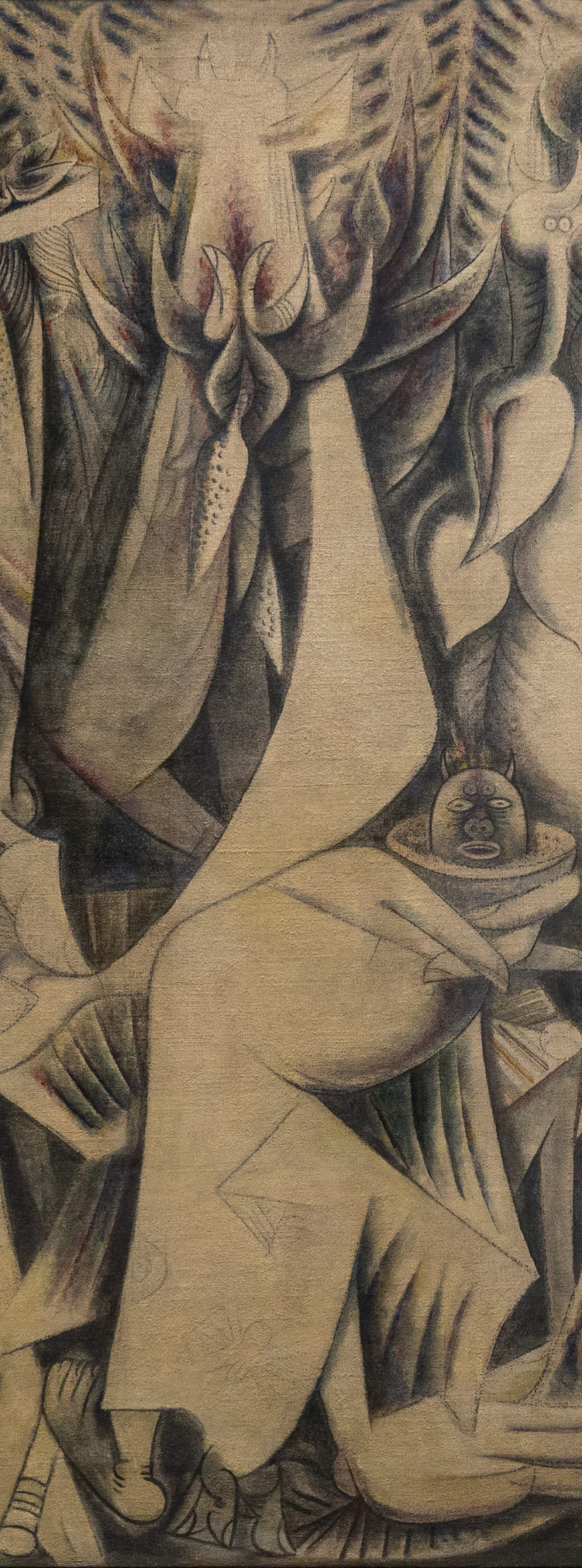

Wifredo Lam, The Eternal Presence (An Homage to Alejandro García Caturla), 1944, oil and pastel over papier mâché and chalk ground on bast fiber fabric, 85 1/4 x 77 1/8 inches (Rhode Island School of Design Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Who are these strange mutant creatures? What is happening in this densely filled composition? In this monumental painting, Wifredo Lam leaves no corner unfilled. We are presented with three imposing anthropomorphic figures that stand and confront the viewer curiously. Overlapping bodies and limbs make it difficult to distinguish the figures and their attributes. The monochromatic color palette fuses the figures and the background into a compressed, claustrophobic space. There is no place to move, no place to hide.

An homage

The multicultural surrealist artist Wifredo Lam was born to a Chinese father and Cuban mother of African and Spanish descent and raised in Cuba. His early travels to Europe exposed him to modernist styles, and important friendships with Pablo Picasso and André Breton secured his place among the Parisian avant-garde. Additionally, Lam traveled to Martinique, where he encountered Aimé Césaire and was exposed to his writings on Negritude, a movement that affirmed the value of black culture, heritage, and identity. Lam’s hybrid animal-human figures and fragmented, flattened compositions draw from a variety of sources, including his Afro-Cuban culture, his experimentation with Surrealist techniques like automatism and cadavre exquis, as well as his interests in Chinese cultural and aesthetic traditions.

Lam dedicated The Eternal Presence to the Cuban composer Alejandro García Caturla, who had been murdered four years earlier at the age of 34. In his musical compositions, Caturla blended elements of European and African culture, becoming a leader of Afrocubanismo, which was an artistic and social movement that focused on the recognition and assimilation of African cultural features present in Cuban society. This blending of cultures resonated with Lam’s artistic objectives. The Eternal Presence depicts a majestic, ambiguous creature in the center accompanied by two fantastical, mythical beings. This triad of figures is still, as if in a trance-like state. The thick palm-tree fronds in the background recall Cuba’s tropical climate and are featured in many of Lam’s paintings, like Fruta Bomba from 1944.

Wifredo Lam, La Fruta Bomba, 1944, oil on canvas, 154.7 x 125 cm (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid)

The Horse

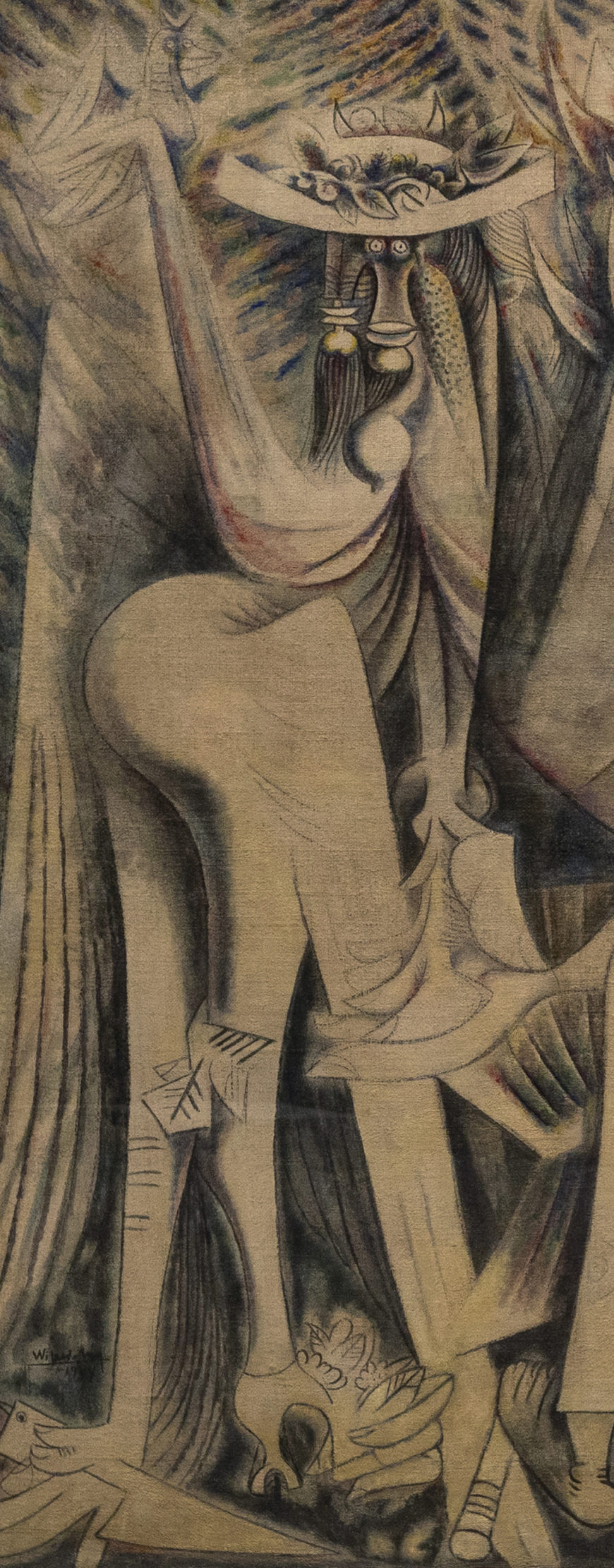

Wifredo Lam, The Eternal Presence (An Homage to Alejandro García Caturla), detail, 1944, oil and pastel over papier mâché and chalk ground on bast fiber fabric, 85 1/4 x 77 1/8 inches (Rhode Island School of Design Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The figure on the left of The Eternal Presence is a femme-cheval, or female-horse, figure. Lam had begun introducing horse-like motifs into his work in the 1940s, inspired by the Afro-Cuban religion of Santería that blends Yoruba spirituality with some aspects of Roman Catholicism.

Within an Afro-Cuban context, the horse figure can be interpreted as an incarnation of an orisha (divine spirit) and its presence refers to the process of being possessed during sacred ceremonies. In Santería rituals, the practitioner is referred to as a “horse” and undergoes a spiritual transformation. [1]

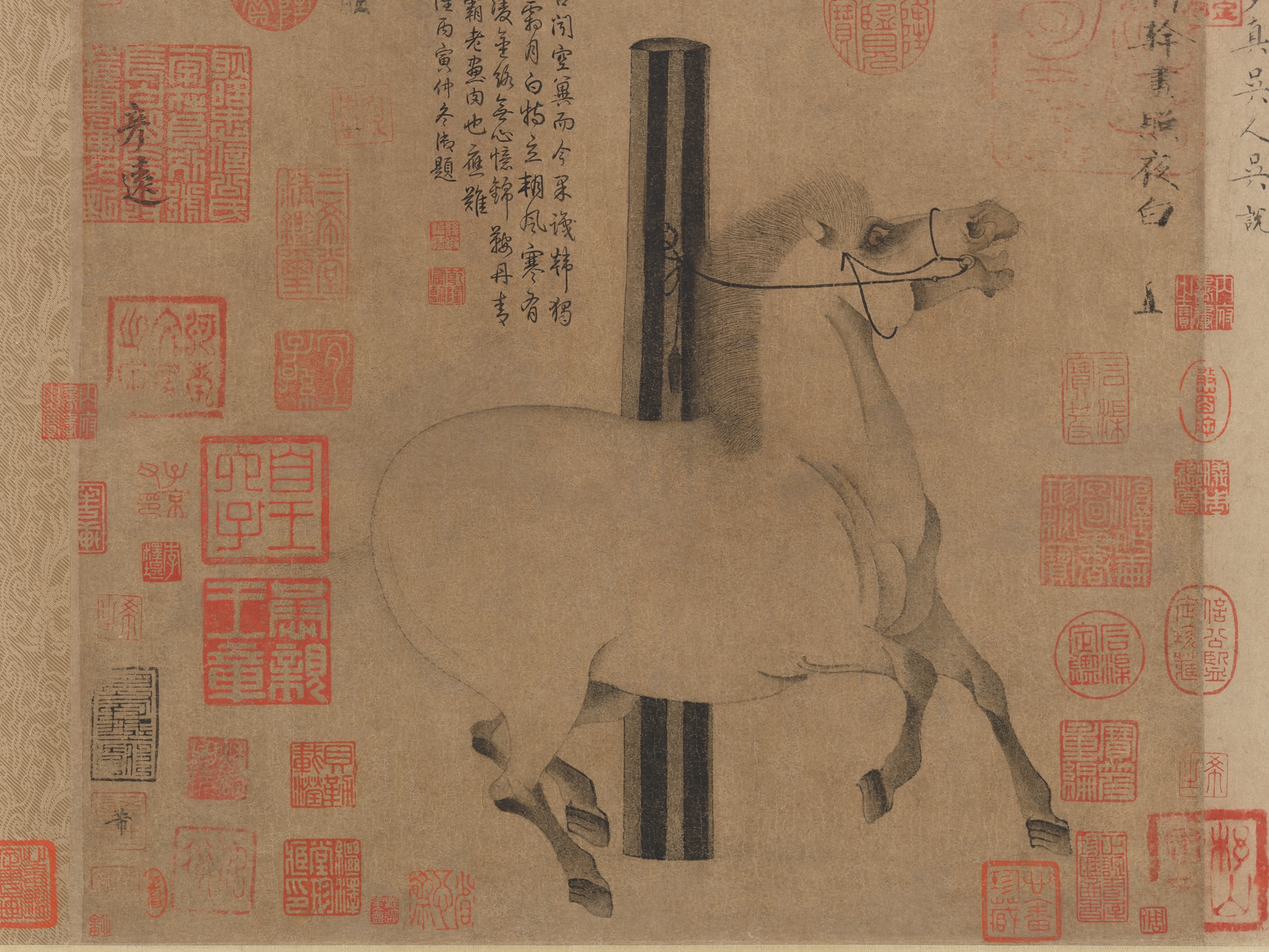

In Chinese culture the horse has a long history of pictorial and poetic representation and may have held personal significance for Lam. Horses were particularly revered in China because of their military and political usefulness, as well as their role in the mythology of early China.

As close kin to dragons and supernatural beings, horses were also believed to have spiritual meaning and were known to guide believers on heavenly journeys. Represented in ornamental bronze masks, jade figurines, terracotta sculptures, ink wash paintings, and poetry, horses were a predominant subject throughout China’s history.

The Chinese had a notable presence in Cuba since the nineteenth century when Lam’s father immigrated. [2] As the youngest child, Lam had a special relationship with his father. Lam fondly remembered when his father would create silhouettes of horses galloping across the walls during Chinese festivals. [3]

In The Eternal Presence, the feminine femme-cheval figure wears a wide-brimmed hat and high heels and her striking curves resemble figures seen in other paintings from the period, such as Lam’s renowned The Jungle from one year earlier. Her horse-mask protects and guides her on a spiritual journey.

Han Gan, Night-Shining White, c. 750, Tang Dynasty, China, ink on paper, 30.8 x 34 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Religious syncretism

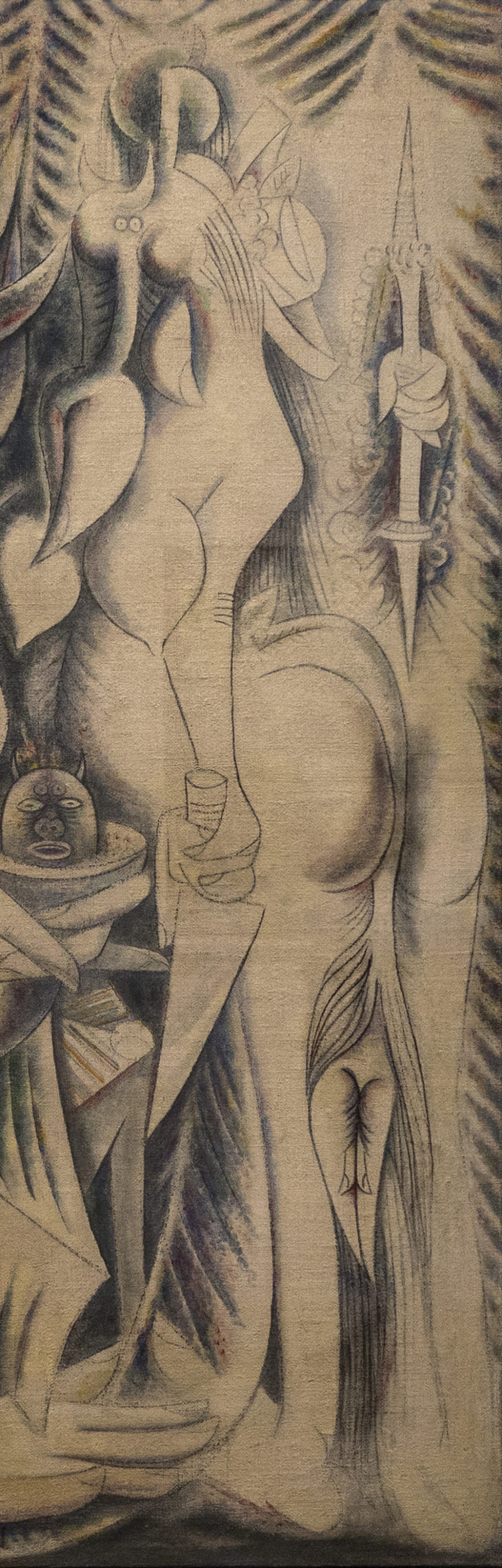

Wifredo Lam, The Eternal Presence (An Homage to Alejandro García Caturla), detail, 1944, oil and pastel over papier mâché and chalk ground on bast fiber fabric, 85 1/4 x 77 1/8 inches (Rhode Island School of Design Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The figure on the right holds a knife and a “palo congo,” the weapon of Changó, the warrior and master of thunder whose sacred power is symbolized by a double-edged axe. In Santería, Changó is an orisha that is often syncretized with Saint Barbara or Saint Jerome. Religious and artistic fusion surrounded Lam.

The Chinese deity Sanfancón is an example of a syncretic form of worship that developed combining Chinese with Afro-Cuban and Christian traditions. The deity is the synthesis of the orisha Changó with the cult of Kuan Kong and Saint Barbara. [4] The right-most Changó figure, who peers outward as his distorted body seems to emerge out of the thick palm-fronds that surround him, could also be interpreted as Sanfancón.

Lam’s second wife, German scientist Helena Holzer, noted that upon their arrival in Havana in 1941, the couple would visit bookstores in Old Havana discovering books on Oriental philosophies and alchemy. [5] These Oriental philosophies enriched their conversations and influenced Lam’s subject matter. Holzer and Lam discussed the symbolism of the number three in different cultures. In Chinese philosophy, the two opposing forces Yin (dark, feminine) and Yang (bright, masculine), combine with Tao, the path that is in harmony with nature.

The number three in the I Ching is the symbol “Chun” which represents birth and new beginnings emerging from chaos. Three in the Holy Trinity is the Father, Son and Holy Spirit, indicative of life, sacrifice, and forgiveness.

Following these conversations, Lam began painting compositions with three figures, such as The Eternal Presence and The Wedding (1947). Holzer explains the subject matter of The Eternal Presence as

… a trinity representing the bird of love and the weapon of destruction (the opposites Yin and Yang) flanking the supreme Tao in the center. [6]

Referencing life, sacrifice, and new beginnings, the painting is an appropriate homage to his late friend Cartula. The central Tao figure with a multiple horned head also evokes the orisha Elegua, the deity of roads and paths. He is portrayed frontally with two oversized arms that cross his body. His darker upper body recedes into the background, while his lower body suggests a surrealist doubling of forms.

Wifredo Lam, The Eternal Presence (An Homage to Alejandro García Caturla), detail, 1944, oil and pastel over papier mâché and chalk ground on bast fiber fabric, 85 1/4 x 77 1/8 inches (Rhode Island School of Design Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

On the one hand, the light-filled space could be the figure’s legs draped in a robe. His right hand holds a plate with a face. On the other, the unfilled shape suggests a hunched-back figure. The perspective is disorienting and the conflation illegible, allowing for a multiplicity of interpretations. The eyes peer forward as if inviting the viewer to speculate on the potential meanings of this intriguing image.

Wifredo Lam, The Eternal Presence (An Homage to Alejandro García Caturla), 1944, oil and pastel over papier mâché and chalk ground on bast fiber fabric, 85 1/4 x 77 1/8 inches (Rhode Island School of Design Museum; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In the eye of the beholder

Lam’s figures stem from and connote transcultural meanings drawing on the various spiritual and artistic ideas that surrounded him. He merged Afro-Cuban Santería, the tropical vegetation of his native land, the Chinese philosophies of the Yin, Yang, and Tao doctrine, and alchemical teachings into his visual representations. The latter exposed him to the belief that sublimation could be achieved through transmutations, that spiritual and intellectual elevation were intertwined with the imagination.

Lam viewed art as a dialogue between the viewer and the figures on the canvas. He believed that art could evoke multiple responses that could change from one day to the next depending on one’s mood. This is enhanced by the multiplicity of his symbolism, where one motif might infer various, diverse meanings, drawing on his multicultural heritage, influences, and interests.

Notes:

- Julia Herzberg, “Wifredo Lam: The Development of Style and World View, The Havana Years, 1941–1952,” in Wifredo Lam and his Contemporaries, ed. Maria R. Balderrama (New York: Studio Museum in Harlem, 1992), 33.

- See Kathleen López, Chinese Cubans: A Transnational History (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2013; Lisa Yun, The Coolie Speaks (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2008).

- Antonio Nuñez Jiménez, Wifredo Lam (Havana: Editorial Letras Cubanas, 1982), 54.

- Frank F. Scherer, “Sanfancón: Orientalism, Self-Orientalism, and ‘Chinese Religion’ in Cuba,” in Nation Dance: Religion, Identity, and Cultural Difference in the Caribbean, ed. Patrick Taylor (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001), 164.

- Helena Holzer Benitez, Wifredo and Helena, My Life with Wifredo Lam, 1939–1950 (Lausanne: Acatos, 1999), 27, 104.

- Ibid., 107.

Additional resources

Lowery Stokes Sims, Wifredo Lam and the International Avant-Garde, 1923–1982 (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2002).

Mey-Yen Moriuchi, “Locating Chinese Culture and Aesthetics in the Art of Wifredo Lam,” in Afro-Asian Connections in Latin America and the Caribbean, eds. Debra Lee-DiStefano and Luisa Ossa (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2018), 2760.

Read the Wifredo Lam Room Guide at the Tate Modern

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”wifredolam,”]