Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas), 1939, oil on canvas, 67-11/16 x 67-11/16″ (Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City)

Indelible marks

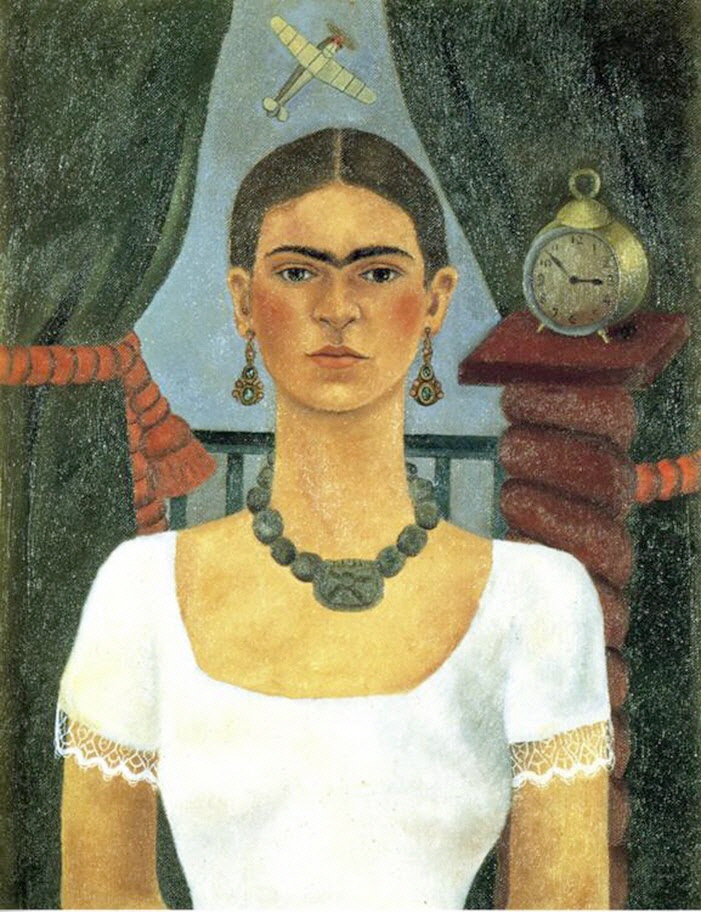

Facial hair indelibly marks the self-portraits of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo. In an era when women still wore elaborate hairstyles, hosiery, and attire, Kahlo was a rebellious loner, often dressed in indigenous clothing. Moreover, she lived as an artist during a period when many middle-class women sacrificed their ambitions to live entirely in the domestic sphere. Kahlo flouted both conventions of beauty and social expectations in her self-portraits. These powerful and unflinching self-images explore complex and difficult topics including her culturally mixed heritage, the harsh reality of her medical conditions, and the repression of women.

The double self-portrait The Two Fridas, 1939 features two seated figures holding hands and sharing a bench in front of a stormy sky. The Fridas are identical twins except in their attire, a poignant issue for Kahlo at this moment. The year she painted this canvas she was divorced from Diego Rivera, the acclaimed Mexican muralist. Before she married Rivera in 1929, she wore the modern European dress of the era, evident in her first self-portrait (left) where she dons a red velvet dress with gold embroidery. With Rivera’s encouragement, Kahlo embraced attire rooted in Mexican customs.

Dress

In her second self-portrait (left) her accessories reference distinct periods in Mexican history (her necklace is a reference to the pre-Columbian Jadite of the Aztecs and the earrings are Spanish colonial in style) while her simple white blouse is a nod to peasant women.

Frida Kahlo, Frieda and Diego Rivera, 1931, oil on canvas, 100.01 x 78.74 cm (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art)

The portraits from the 1930s reflect Kahlo’s growing penchant for indigenous attire and hair-styling, as is evident in Frieda and Diego Rivera, 1931 and The Two Fridas. Yet Kahlo never abandoned dressing her subjects and herself in mainstream, European dress; her female relatives wear non-indigenous clothing in My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree), 1936 (below).

Frida Kahlo, My Grandparents, My Parents, and I (Family Tree), 1936, oil and tempera on zinc, 30.7 x 34.5 cm (Museum of Modern Art)

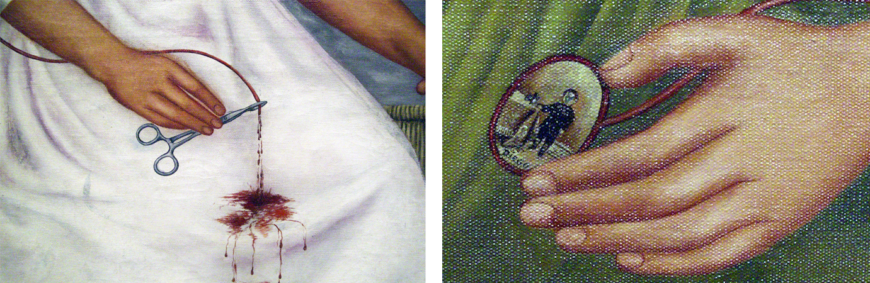

In this painting, the bridal dress Kahlo’s mother wears is reminiscent of the white, stiff-collared dress the artist wears in The Two Fridas. Indeed, the grotesque view into each woman’s insides is heightened by the virginal whiteness of both dresses.

Left: Frida Kahlo, Frieda and Diego Rivera, 1931, oil on canvas, 100.01 x 78.74 cm (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art); right: Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas), 1939, oil on canvas, 67-11/16 x 67-11/16″ (Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City)

In her brief lifetime, Kahlo painted about two hundred works of art, many of which are self-portraits. With the exception of a few family trees, the double-portrait with Rivera and The Two Fridas represents a departure in her oeuvre. If a self-portrait by definition is a painting of one’s self, why would Kahlo paint herself twice? One way to answer this question is to examine The Two Fridas as a bookend to the 1931 portrait, Frieda and Diego Rivera. Though this painting was meant to celebrate the birth of their union, their tentative grasp seems to reflect Kahlo’s misgivings about her husband’s fidelity. By contrast, the double self-portrait, though laden with suffering, exhibits resilience.

Frida Kahlo, Details of The Two Fridas (Las dos Fridas), 1939, oil on canvas, 67-11/16 x 67-11/16″ (Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City)

Anatomy of Two Fridas

The two Fridas clasp hands tightly. This bond is echoed by the vein that unites them. Where one is weakened by an exposed heart, the other is strong; where one still pines for her lost love (as underscored by the vein feeding Rivera’s miniature portrait), the other clamps down on that figurative and literal tie with a hemostat.

Human anatomy is often graphically exposed in Kahlo’s work, a topic she knew well after a childhood bout with polio deformed her right leg and a bus accident when she was eighteen years old left her disabled and unable to bear children. She would endure 32 operations as a result. Kahlo utilized blood as a visceral metaphor of union, as in the 1936 family portrait (above) where she honors her lineage through these bloody ties. She returns to this metaphor in The Two Fridas though with the added impact of two hearts, both vulnerable and laid bare to the viewer as a testament to her emotional suffering.

“I am the person I know best”

Photographs by artists within her milieu, like Manuel Alvarez Bravo and Imogen Cunningham, confirm that Kahlo’s self-portraits were largely accurate and that she avoided embellishing her features. The solitude produced by frequent bed rest—stemming from polio, her near-fatal bus accident, and a lifetime of operations—was one of the cruel constants in Kahlo’s life. Indeed, numerous photographs feature Kahlo in bed, often painting despite restraints. Beginning in her youth, in order to cope with these long periods of recovery, Kahlo became a painter. Nevertheless, the isolation caused by her health problems was always present. She reflected, “I paint self-portraits because I am so often alone, because I am the person I know best.”

Additional resource

Watch a video on Frida Kahlo’s Frieda and Diego Riviera (1931)