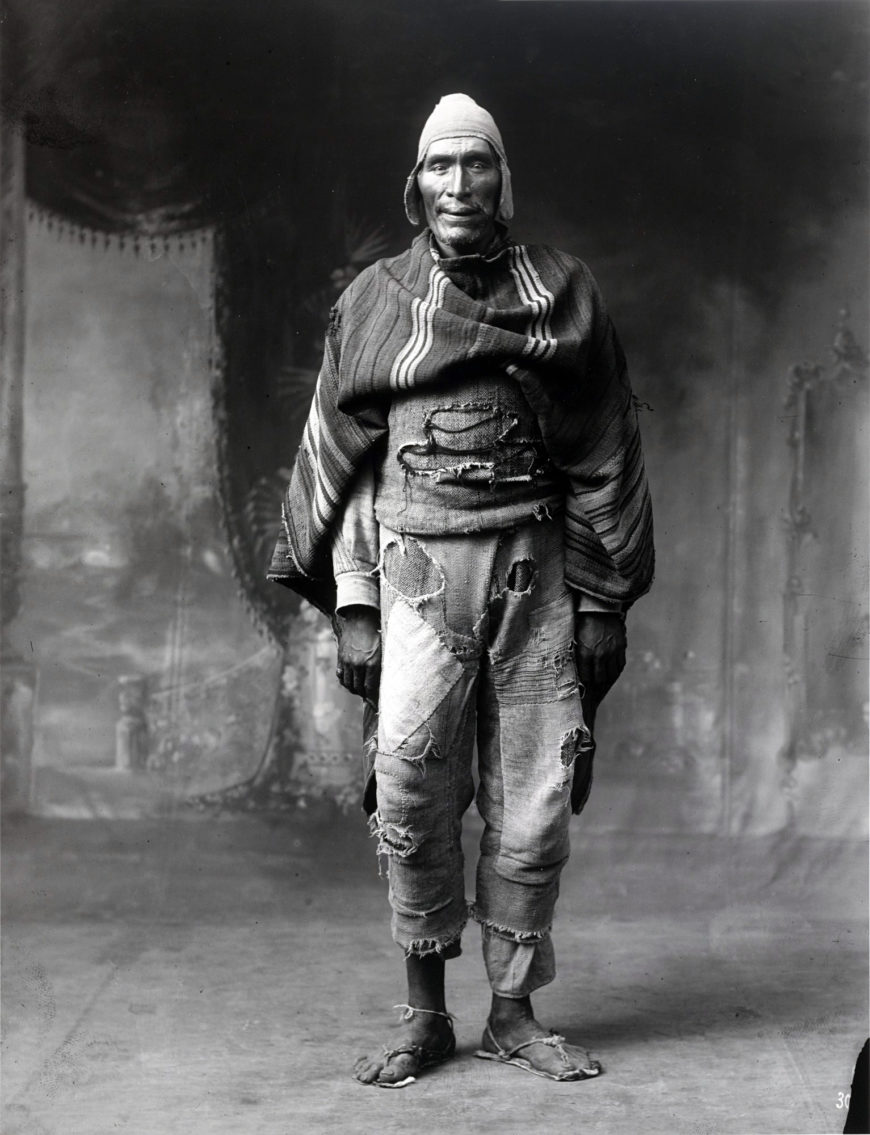

Martín Chambi, Juan de la Cruz Sihuana, Cuzco Studio, 1925, gelatin silver print, printed 1978 (Museum of Modern Art)

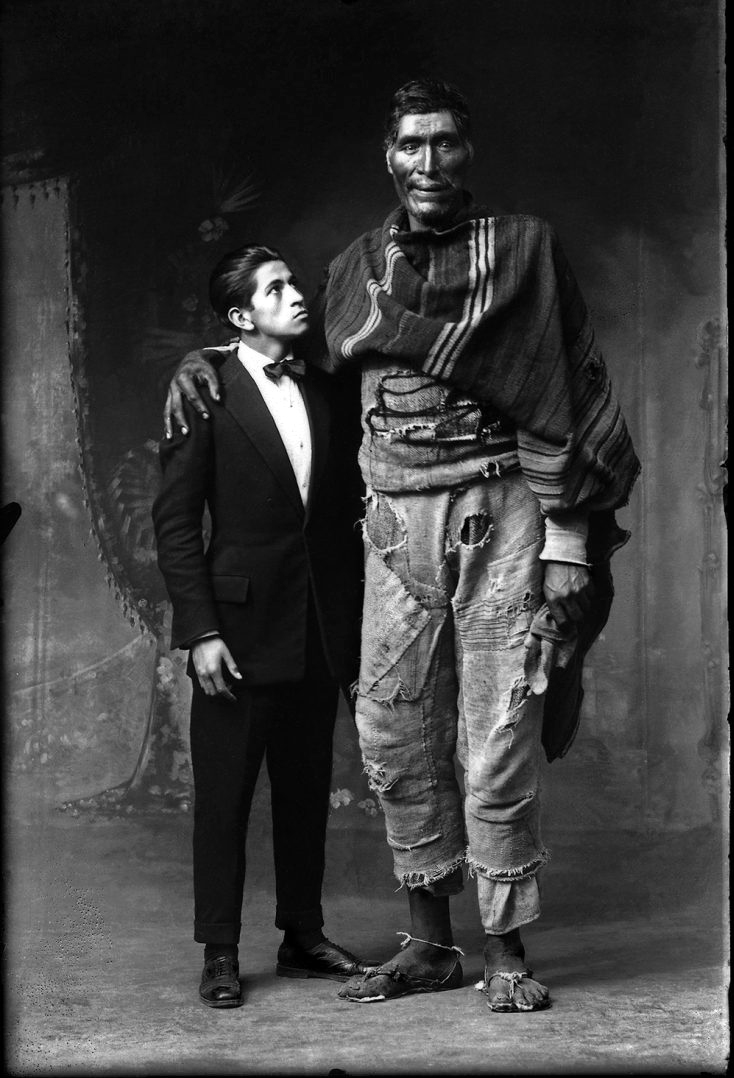

Martín Chambi, Victor Mendivil and the Llusco Giant, Cuzco, 1925, gelatin silver print, 47 × 31.5 cm (The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)

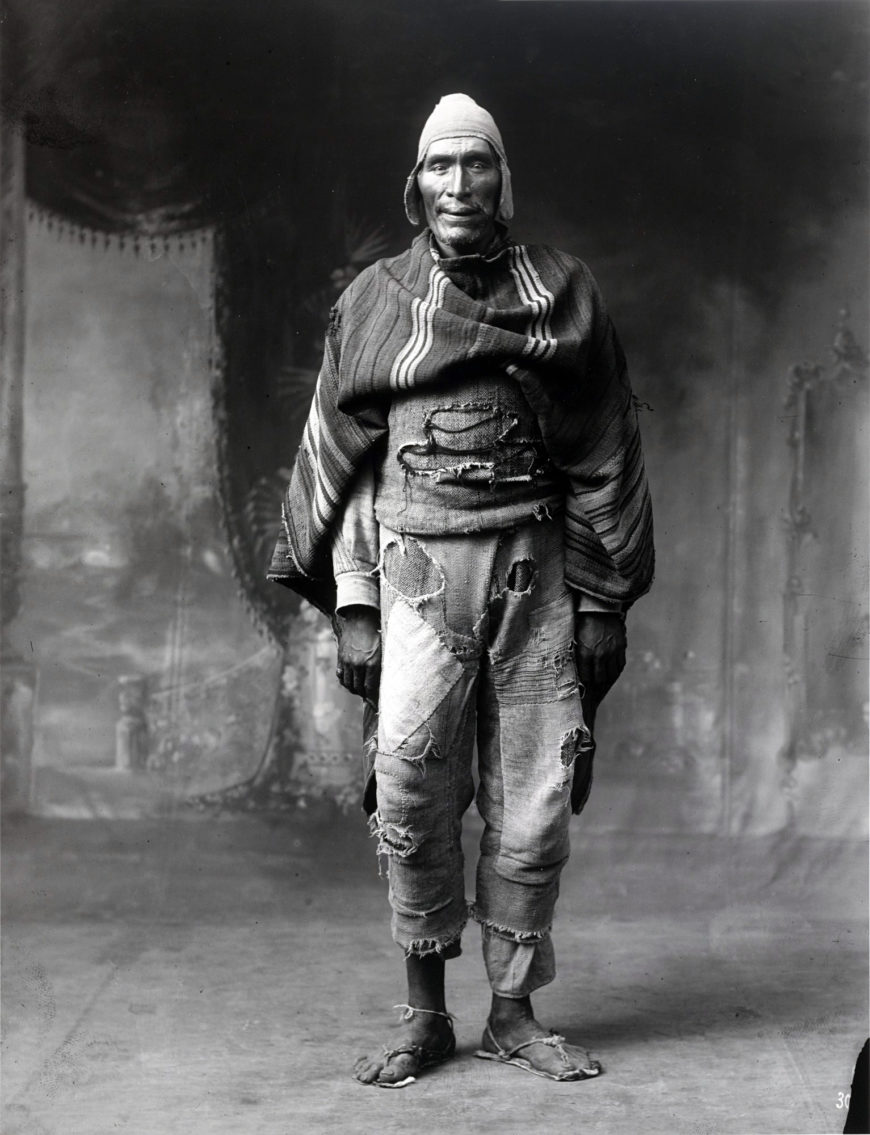

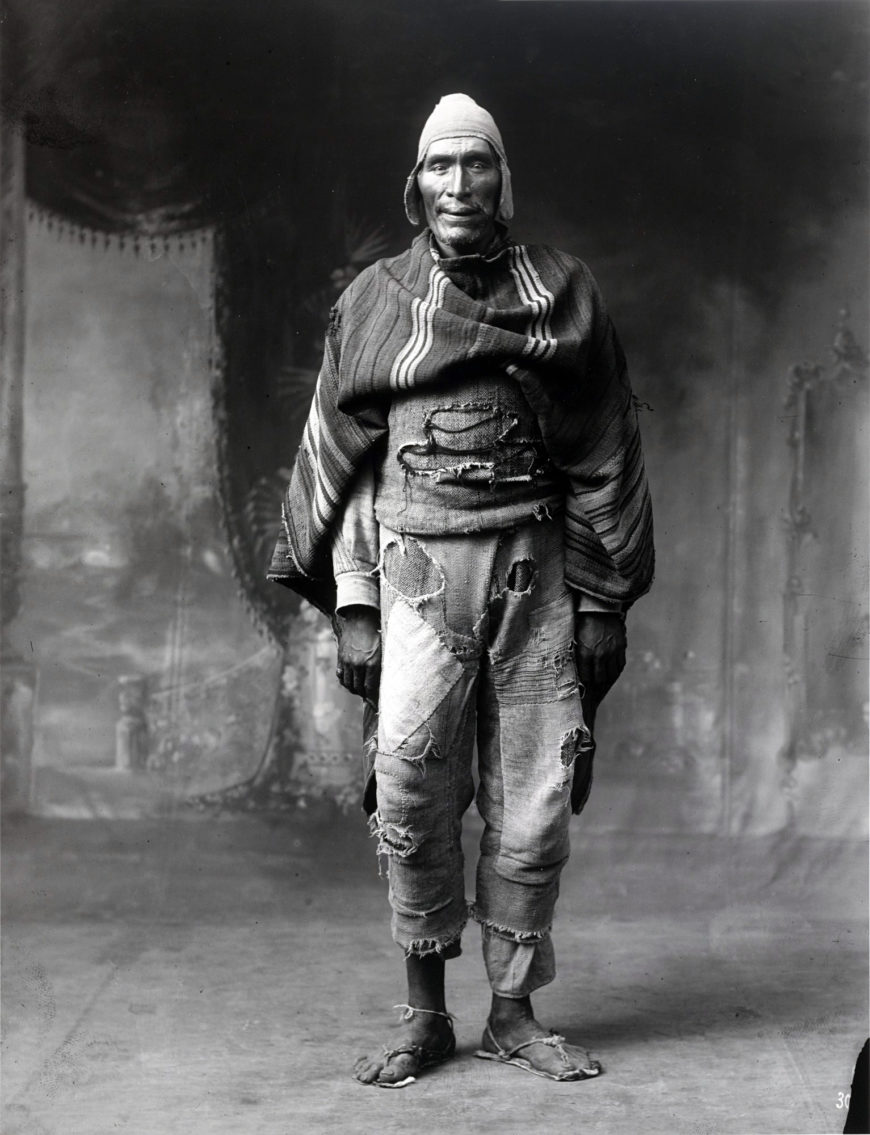

The towering figure of Juan de la Cruz Sihuana nearly scrapes the edges of a portrait photograph created by Cusco photographer Martín Chambi in 1925. His barely shodden feet are tied into flimsy sandals, and his traditional chullo cap stretches towards the picture’s upper edge. Chambi’s decision not to include any props, which were common in studio portraits of the time, makes it difficult to judge Sihuana’s scale. At least one other photograph of Sihuana with his arm around Víctor Mendívil (Chambi’s assistant) gives us a better sense of the former’s unusual height of almost seven feet.

Chambi created these pictures of Sihuana at his own initiative and expense—they were not commissioned portraits. He did not make much money off of the images after they were created either. Chambi’s photograph was originally published in the Lima-based newspaper El Peruano in the article “The Giant of Paruro?”, but it was not printed on postcards, displayed in exhibitions, or published in additional formats during Chambi’s lifetime. The photograph’s limited circulation may indicate Chambi’s rejection of historical narratives that exoticized and “othered” native Peruvians. Since the early colonial period, European writings and illustrations produced in and about Peru had treated its Indigenous populations derisively. At best, Indigenous people were portrayed as innocents incapable of self-governance; at worst, they were dehumanized as devil-worshiping heathens in need of conversion and control. [1]

To understand Chambi’s motivations for creating this image, we need to understand the symbolic, political, and cultural importance of Indigenous peoples in modern Peru.

Chambi, the photographer

Chambi’s perspective on his country’s native cultures was shaped by his mixed cultural heritage and impoverished upbringing. Born in a remote Andean village in southern Peru to a family that worked in mining and farming, Chambi spoke Quechua (an Indigenous language that had also been the primary language of the Inka) and received limited formal schooling. He was first exposed to photography by a British photographer who worked for a local mining company. As a teenager, Chambi panned for gold to earn money, which he used to travel to the city of Arequipa for photographic training.

Despite these humble origins, the eventual success of Chambi’s photographic studio in Cusco made him part of the city’s vibrant intellectual community. Photography provided Chambi with opportunities to network with the artists and other public figures who came to him to have their portraits taken. Chambi’s relationships with artists, writers, and politicians drew him into Peru’s indigenista circles. The indigenismo movement, discussed below, embraced Indigenous cultural forms and peoples as the core of Peruvian national identity. Ultimately, Chambi’s portrait of Sihuana demonstrates how he amalgamated influences from Peru’s Indigenous cultures, European portraiture conventions (like centered subjects, painted backdrops, and controlled and even lighting), and his own creative vision to create an image that both celebrated and romanticized Peru’s Indigenous population—as the rest of this essay unpacks.

Sihuana, the Giant of Paruro

Martín Chambi, Juan de la Cruz Sihuana, Cuzco Studio, 1925, gelatin silver print, printed 1978 (Museum of Modern Art)

Chambi’s photograph of Sihuana is a sensitive portrait of an Indigenous Peruvian man in traditional dress, including a draped poncho and chullo cap. Created in Cusco (the historical capital of the Inka civilization) in 1925, Chambi’s photograph reflects the prevalence of European portrait conventions even in predominantly Indigenous areas of independent Peru. Chambi carefully lit Sihuana so that his bronzed skin glowed against the dark background. The raking light creates chiaroscuro-like effects that outline the deep folds of his poncho and draw attention to the patches sewn onto his trousers. A painted cloth of honor (the ornamental draper behind Sihuana) heightens the sense of spatial recession and brings a hint of classicism into the photograph via the bucolic landscape upon which the curtain opens.

José Gil de Castro, José Bernardo de Tagle y Portocarrero, Marqués de Torre-Tagle, 1828, oil on canvas, 215.70 x 130.30 cm (MALI)

Sihuana’s direct gaze confronts the viewer. His stance and surroundings mimic painted portraits of a century earlier, like Afro-Peruvian portraitist José Gil de Castro’s portrayal of the Marques de Torre-Tagle. Although Gil de Castro never traveled to Europe, he became famous for his ability to represent the Peruvian elite in grand style. Much like Sihuana, the gentlemanly Tagle is positioned in front of a cloth of honor and surrounded by decorative objects that help to signal his status. While his dress is much more refined than Sihuana’s, his body position and direct gaze foreshadow those of Chambi’s sitter. As a photograph, Chambi’s image is decidedly sparser and lacks the vibrant color of Gil de Castro’s creation, but twentieth-century Peruvians would have easily spotted the visual parallels between Chambi’s image and the aristocratic portraits of yesteryear.

The focal point of the image is Sihuana’s quizzical expression. Some scholars have suggested that as a portraitist, Chambi was interested in individuality rather than in creating typifying views that drew attention to subjects’ ethnicities, cultural specificities, or their physical features. [2]

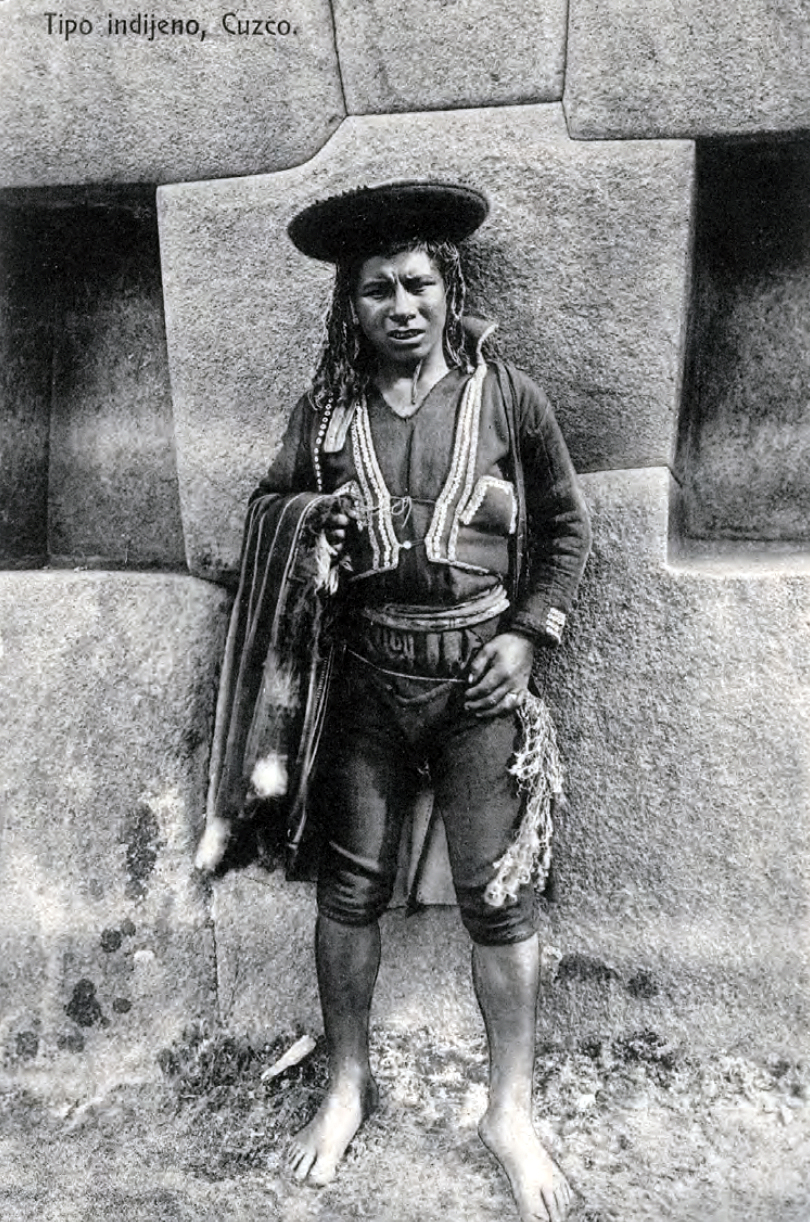

Throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, photography was frequently used by anthropologists, ethnographers, amateur explorers, law enforcement, and artists to categorize people. In creating his portrait of Sihuana, Chambi drew from the nineteenth-century tradition prevalent across Latin America of creating tipos or types. Tipo photography and illustration often depicted members of urban society dressed in their stereotypical clothing and plying the tools of their trade. The images attempted to show the costuming, foodstuffs, and artisanal productions of the region in which they were produced. However, they were also used as caricature to poke fun at women and non-white citizens. The pictures were often gathered into albums (accompanied by satiric texts) and printed on postcards which circulated both domestically and internationally.

Chambi’s mentor, Max T. Vargas, was well known for his tipos. Chambi spent nine years as an apprentice in Vargas’s Arequipa studio, so he would have been familiar with Vargas’s pictures of “old beggars” and “Indian types.” For example, Vargas’s photo of a “Tipo indigeno” does not give the name of his sitter, it merely identifies him as an “Indigenous type” from Cusco. The man poses in front of a wall of Inka masonry linking him to the pre-Columbian past, rather than to contemporary society and politics. His stance, attitude, and dress do little to communicate anything beyond the fact of his Indigeneity and do not illustrate his relationship to the modern world. Because tipos tended to depict members of the lower socio-economic classes and focus on tradition, their imagery represented Peru as timeless, unchanging, and without access to modern technology (even when they were made with a camera).

In contrast, Chambi’s photograph of Sihuana can be read as a portrait of modern Indigeneity. [3] Sihuana’s dress identifies him as Indigenous, but his extraordinary height—especially in Peru, whose population has one of the shortest average heights in the world—defies neat categorization. By emphasizing Sihuana’s individuality, Chambi resists his sitter’s categorization into a common type. Instead of giving the portrait a generic or stereotypical title, Chambi identified Sihuana by name. This gesture elevated poor and Indigenous sitters like Sihuana to the level of Chambi’s upper-class, paying clients who came to have their portraits taken in front of the same backdrop. Furthermore, by taking Sihuana’s portrait in the popular style of the day, Chambi situated him firmly in the present. We do not think of Sihuana as an anonymous Indigenous subject whose life is rooted in culture and traditions tied to the past, but as a distinct individual capable of navigating a modernizing world.

Chambi also conveys Sihuana’s modernity through his photographic aesthetic. The relatively uncluttered studio space, incredibly clear image, and strong contrasts of light and dark all reflect Chambi’s modern photographic style. While nineteenth-century photographers often preferred staged, narrative imagery and atmospheric effects, twentieth-century practitioners across the globe embraced “straight photography” that privileged sharp focus and heightened detail. Straight photographers, including Chambi, viewed their work as more documentary than allegorical. They often placed a single subject in the center of the photo, allowing for close examination. Nevertheless, straight photography was highly evocative, embracing the stark tonal contrasts of black-and-white film for dramatic effect, as Chambi does in his portrait of Sihuana.

Indigenismo

Chambi’s portrait of Sihuana is more subtle than Vargas’s tipo, but it is not unbiased. There were significant imbalances of wealth and influence between the middle-class, cosmopolitan world Chambi inhabited, and that of the Indigenous Sihuana. [4] Early-twentieth-century Peruvian intellectuals—including Chambi—were intensely interested in the various Indigenous cultures of Peru, which they viewed as the root of Peruvian national identity. Peruvian Modern art—including Chambi’s photography—was shaped by the values and ideas of a group of Cusco-based philosophers who embraced indigenismo, the belief that regional identity should spring from Indigenous cultural forms and that Indigenous peoples should be more dominant in local politics.

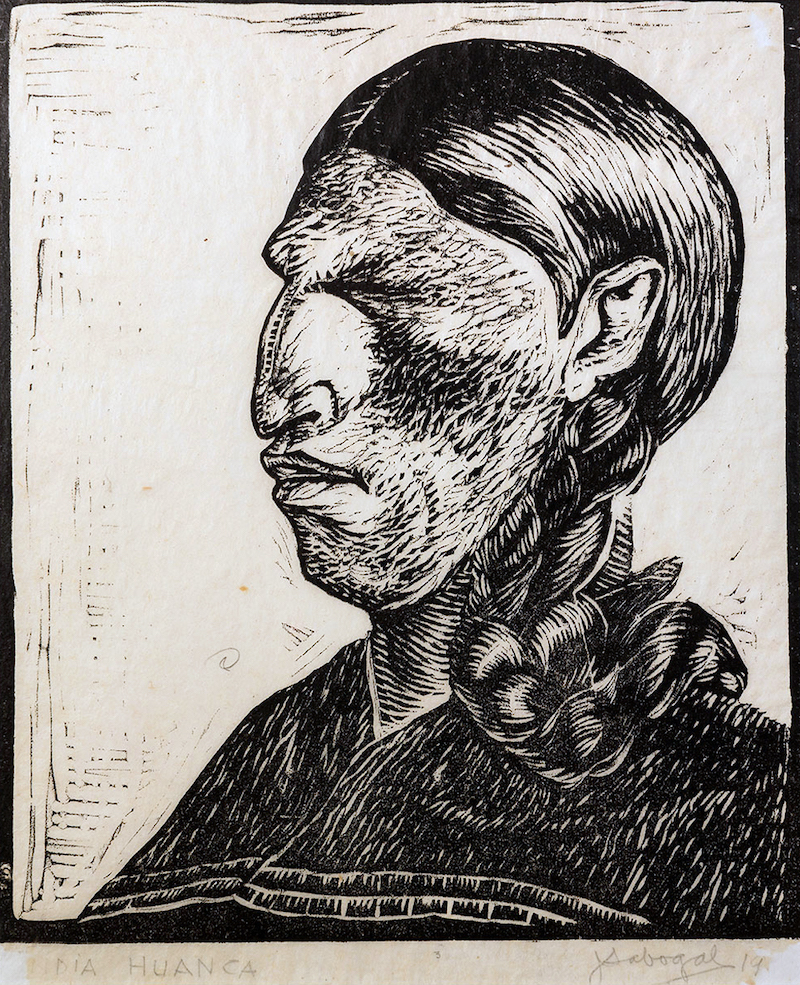

José Sabogal, India Huanca, 1930, woodcut (OAS AMA | Art Museum of the Americas Collection)

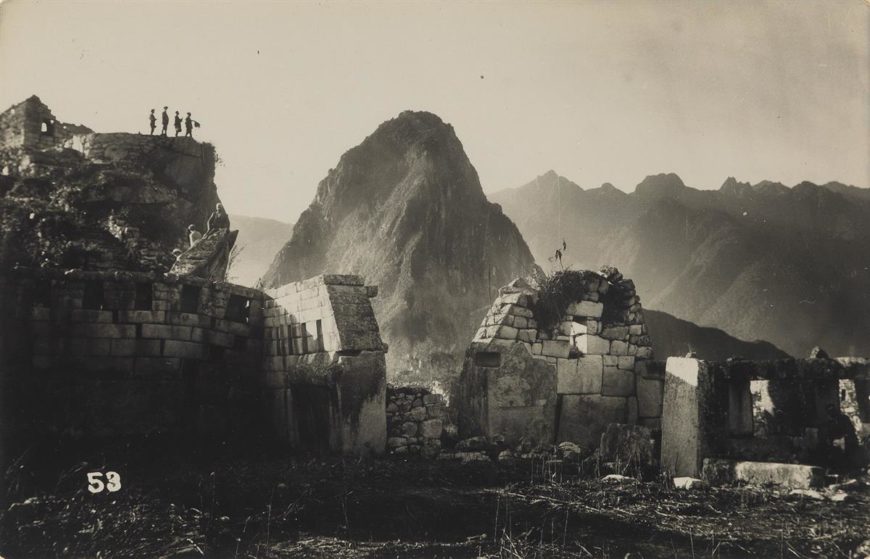

However, indigenismo was largely championed by the mestizo (mixed-race) bohemian elite—including Chambi—rather than by people who primarily identified as Indigenous themselves. While artists like Chambi who prescribed to indigenista ideas helped to elevate the visibility of Indigenous peoples, they did little to change the material circumstances of Peru’s Indigenous population, many of whom—like Sihuana—were impoverished. Indigenismo was especially popular in Cusco because the city was the former Inka capital. Chambi was close friends with indigenista artists like José Sabogal and Juan Manuel Figeroa Aznar. He also took early photographs of Machu Picchu after its rediscovery in 1911. For Chambi and the indigenistas, Machu Picchu served as a testament to the brilliance of its Inka builders, reaffirmed their well-deserved place atop Peru’s social hierarchy, and foretold an Indigenous renaissance. [5]

Martín Chambi, Machu Picchu, Cuzco, 1928, gelatin silver print (Museo de Arte de Lima. Donación Natalia Majluf y Ricardo Kusunoki Rodríguez)

Martín Chambi, Juan de la Cruz Sihuana, Cuzco Studio, 1925g, elatin silver print, printed 1978 (Museum of Modern Art)

Chambi’s portrait of Sihuana demonstrates indigenista influence in the way it emphasizes Sihuana’s traditional dress, including its patterning, texture, and style. But some scholars have argued that Chambi’s evocative lighting, close attention to textural detail, and simplified staging portray Sihuana as a doomed romantic figure—a representative of a static culture and dying race that was destined to be supplanted by modern society. [6] Sihuana’s benign expression and inactive pose betray a tension in Chambi’s photograph: while this is a more nuanced view of the Indigenous subject than those produced in previous generations, Sihuana’s tattered clothes still locate him at the bottom of Peru’s social and economic pyramid. Passive and immobile, Sihuana inhabits a modern photographic studio, but does not completely embody the ideals of self-actualization and technological evolution at the heart of Modernity.

As an individual of mestizo heritage from a rural family who rose to the middle-class via adaptation and embracing photographic technologies, Chambi personally experienced the deep divide between Peru’s Indigenous underclasses and the criollo elite. His photographs, which attempted to balance a sympathetic view of Indigenous Peruvians with ongoing practices of exoticization and othering, visualize the inherent paradoxes of early twentieth-century indigenismo.

Chambi’s legacy today is mixed: he is by far the most famous Peruvian photographer of his generation. His distinctive personal style is highly recognizable and demonstrates his mastery of his medium. But his photographs also occupy an ambiguous place in the history of Peruvian indigenismo: part sensitive representations of Indigenous individuals and part idealizations of the tragic “disappearing Indian.”