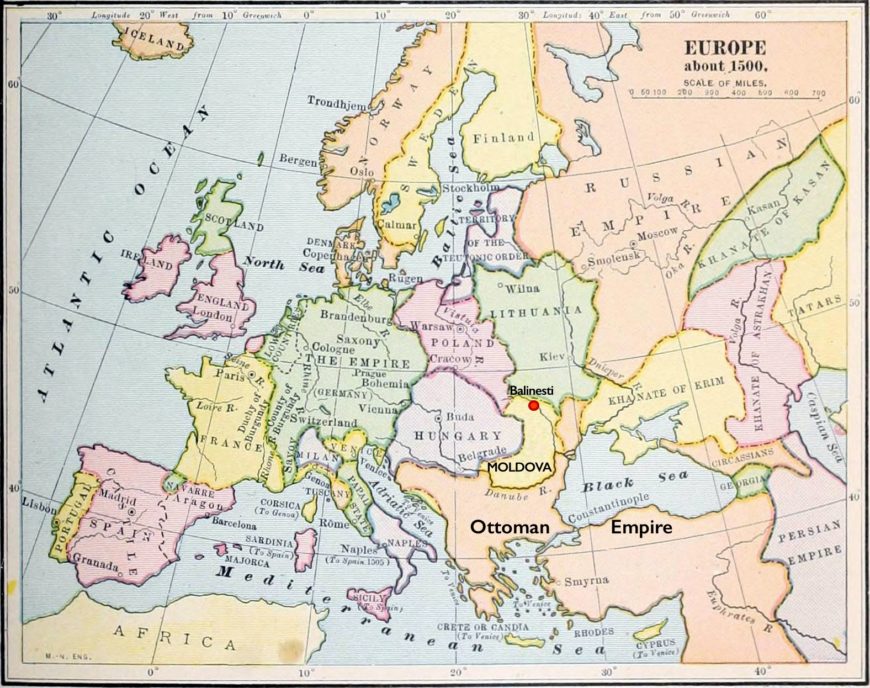

In Bălinești (part the historical region of Moldova, in present-day Romania) stands the bulky silhouette of the private chapel of St. Nicholas.

The chapel was built by a high-level minister in the service of the prince of Moldova — Ioan Tăutu (his official title was “Logothete”). Tautu also served as a diplomat in negotiations with neighboring powers such as the Ottoman Empire and his high standing is reflected in the lavish character of St. Nicholas.

The chapel stands among the finest examples of Moldavian architectural decoration (carved stone elements and polychrome glazed ceramic fixtures) and liturgical painting.

A hallmark of local hybrid architecture

Gothic-style stone carving, St. Nicholas church, 1499 (image: Vlad Bedros)

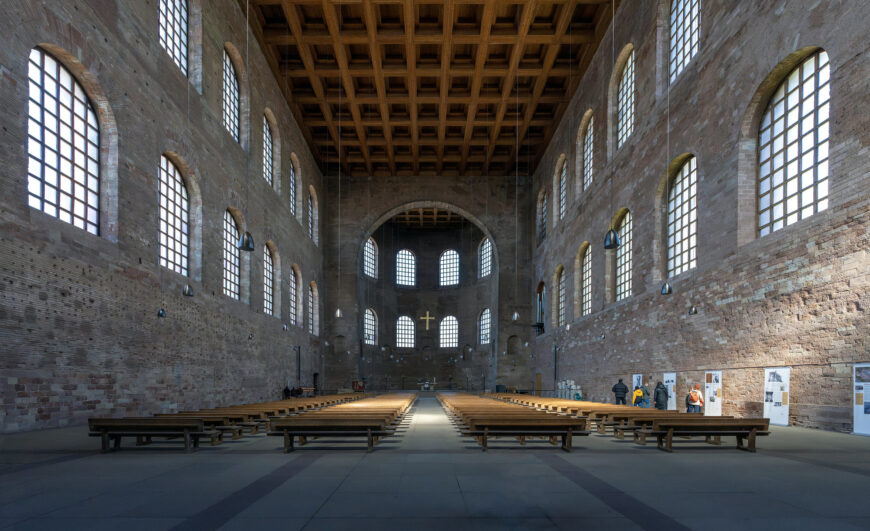

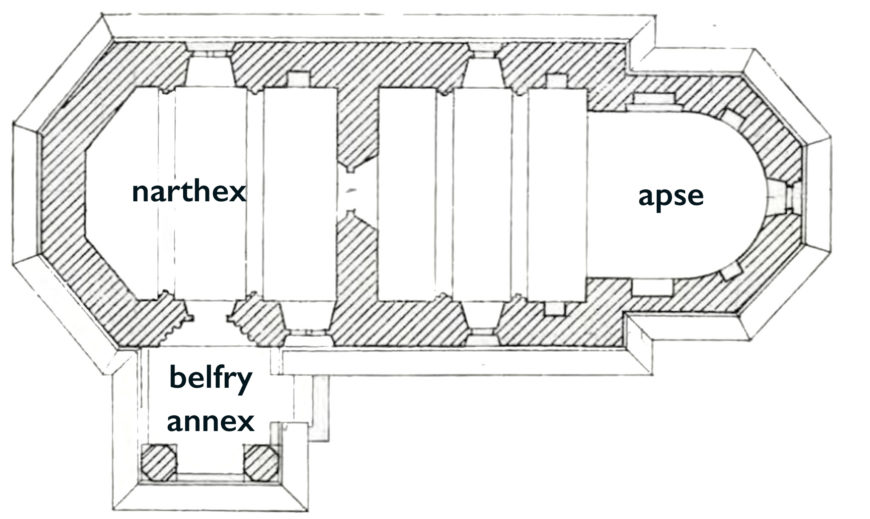

The chapel has a nave with a protruding horseshoe-shaped apse, balanced by a Western European structure, namely the trapezoid ending of the narthex. On the southern wall, a porch surmounted by a belfry marks the entrance and creates a picturesque tower-like annex.

The hybrid nature of this architectural solution — uniting both Eastern (Byzantine) and Western (Gothic) church forms — echoes similar private chapels in the region.

The carved stone details on the church walls are most telling of the infusion of the elegant Gothic style. These carvings are most clearly seen in the exquisite vault of the porch and on its railing, adorned with quatrefoils.

The interior architectural details show Gothic features, too, such as the supporting arches for the barrel vaults in the nave and narthex, which rest upon bundled pilasters. Such transfers from the Western architectural repertoire into the Post-Byzantine tradition (the Byzantine Empire fell to the Ottomans in 1453) were typical of local building practices. For this reason, scholars labeled the architecture of 15th- and 16th-century Moldova as “Byzantine edifices erected by Gothic hands.”

Barrel vaults on fasciculated (bundled) pilasters, Church of St. Nicholas, 1499, Bălinești (image: Vlad Bedros)

Another marker of hybridity is the use of glazed ceramic discs displayed in rows under the eaves.

The glazed ceramic medium was used to draw attention to the main outlines of the building. This use of glazed ceramic elements was not new in Late Byzantine practices; it could be seen throughout the Byzantine world, from Constantinople to the Balkans. But the generous diameter of the ceramic discs, the choice of colors (alternating dark green with ochre and grayish brown), and the inclusion of figural decoration (only present, however, during the last decade of the 15th century) are all unique features of Moldavian ceramic decoration.

Two-tailed mermaid, glazed ceramic disc, outer wall, St. Nicholas Church, 1499, Balinesti, (image: Vlad Bedros)

The Moldavian glazed ceramic discs depict motifs such as the Mermaid, the Manticore, the Lion Rampant, and Moldova’s coat of arms, featuring an aurochs’ head. These motifs helps link this uniquely Moldavian practice to a Late Gothic workshop active in the Moldavian principality at the end of the 15th century.

Frequently, the exteriors were decorated with an iconographic program of outer wall paintings (a typical choice for Moldavian churches). Such paintings hid the churches’ carefully staged stone, brick, and ceramic exterior.

St. George Church, Voronet Monastery, covered in outer mural painting (image: Stanislav Dusik, CC 4.0)

This is the case with logothete Tăutu’s church in Bălinești, too, whose entire exterior received a coat of fresco decoration, preserved today only on the southern sides of the apse, on the belfry, and on the western ending of the narthex.

Fragments of mural painting on the exterior of the church of St Nicholas, 1499, Balinesti (image: Vlad Bedros)

“Gavril, monk and priest, wrote this”

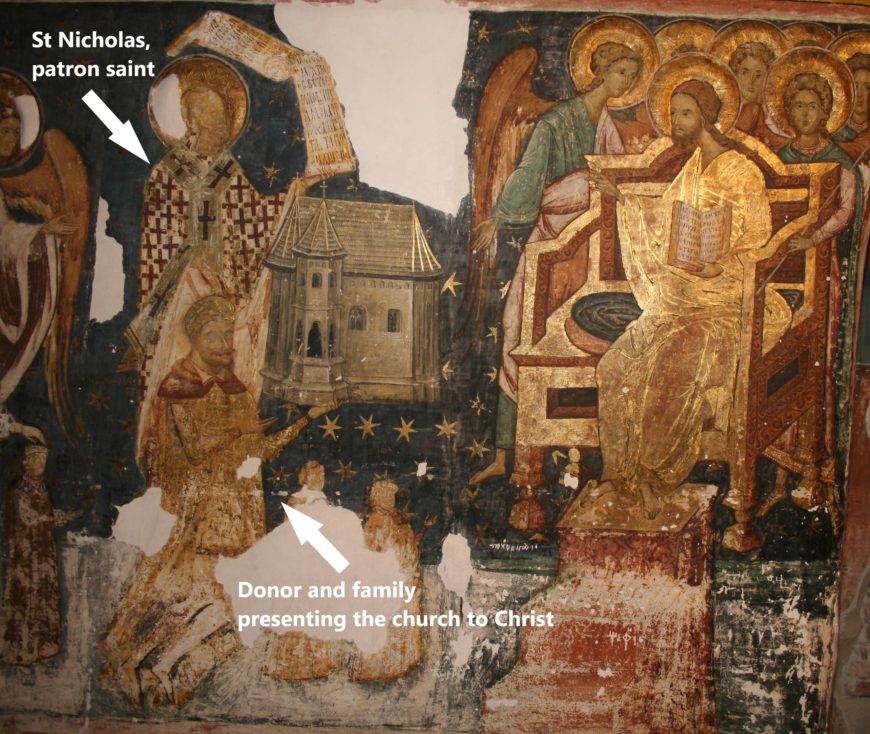

On the western wall of the nave, to the right, stands the majestic votive portrait of the donor (Tăutu) and his family, introduced by the patron saint (St Nicholas) to the enthroned Christ, gleaming in gilded robes and attended by a host of angels.

Medievalist scholar Sorin Ulea found an inscription on the painted footstool: писаxь гавриль їрмонах (pisah’ gavril’ irmonah, lit. I, Gavril, monk and priest, wrote this). According to this scholar, this inscription is the signature of the master painter.

Signature inscription on mural painting, Church of St. Nicholas, 1499, Balinesti (image: Vlad Bedros)

Scholars have long endeavored to identify the names of the church painters and the stylistic changes they engendered. Such painters were Gavril the Hieromonk and Toma from Suceava, both identified by scholar Sorin Ulea, as well as the better-known George from Trikala and Dragoş Coman from Suceava. These painters were agents of artistic development of the so-called “Moldavian school.” However, recent methodological approaches are more cautious of these identifications; they are also skeptical of the concept of the idea of a “national school” such as the “Moldavian school.”

The inscription from the church in Bălinești makes use of the verb писати, pisati, i.e. to write, unusual for a painter’s statement. Using “to write” instead of “to paint” to describe the painter’s activity may emphasize the prescribed nature of the depicted images as well as their “official” status, de-emphasizing the role of the painter’s subjective interpretation. However, placed at the feet of Christ, who is depicted as Rightful Judge of the Second Coming, this barely visible inscription also functions as a perpetual prayer of salvation addressed to Christ by one of the members of the workshop that painted the chapel.

The recent restoration of the frescoes (by a team supervised by Professor Oliviu Boldura and led by Geanina Deciu and Cristian Deciu) brought to light the full gamut of stylistic and iconographic refinement of this ensemble of paintings, which had already been praised—since the very beginnings of local historiography—as one of the most exquisite examples of post-Byzantine wall painting in Moldova. Meticulously restored, the paintings demonstrate a unique blend of South-Eastern Late Byzantine tradition and a discrete Late Gothic imprint.

Paintings of the genealogy of Christ. Upper image showing crowned figures. St. Nicholas Church, 1499, Balinesti (image: Vlad Bedros)

Byzantine heritage on the edge of the Orthodox world

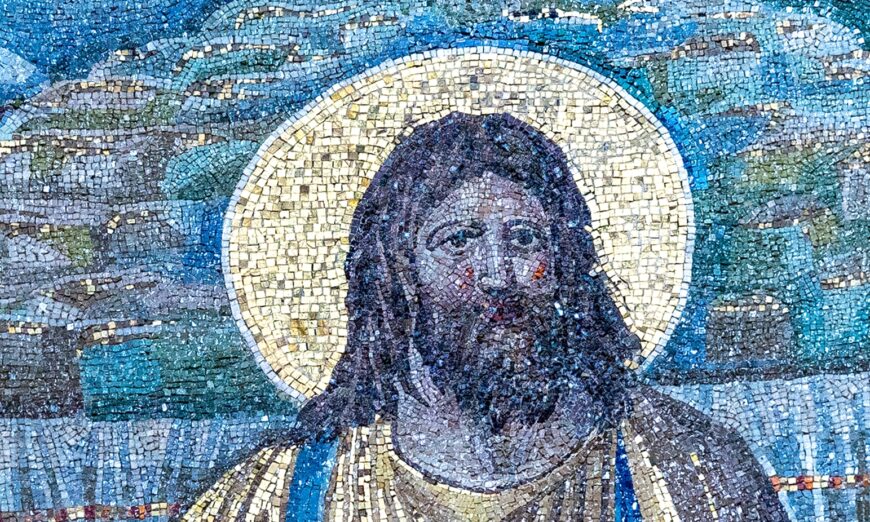

On the arch that joins the sanctuary to the one-aisled naos, four enigmatic scenes create an autonomous cycle. Each depicts a central character flanked by symmetric groups, and one of the four scenes features crowned figures.

This iconography was identified through a comparison with similar scenes from the contemporaneous wall paintings in the church of Voroneț Monastery, where preserved inscriptions reveal that they illustrate the genealogy of Christ.

The actual source of these images came to light only in 1992, when scholar Constanța Costea showed that they copy miniatures from the Gospels of Tsar Ivan Alexander (now in the British Library), illustrating the first chapter from the Gospel according to Matthew. The circulation of this manuscript in Moldova explains its dissemination as model.

Miniature from the first chapter from the Gospel according to Matthew, Gospels of Tsar Ivan Alexander, 1355-56 (British Library)

Costea also showed that the influence of this manuscript was so copiously present in the iconography of the wall paintings that she described the church painters’ reliance on it as a “bookish tendency.” In fact, many of the Moldavian wall paintings created in churches between 1490 and 1530 exemplified the transposition of miniatures from Gospel Books into the realm of fresco decoration. This cross-medium iconographic practice echoes the erudite tendency of Late Byzantine art.

Below the belt of images depicting the genealogy of Christ, the lowermost register is dedicated to standing portraits of saints. The section at the eastern end of the southern wall features courtly representations of saints George and Demetrius, enthroned together on a bench. They brandish their weapons, while George emphatically squeezes a serpent-like monster under his feet—a reference to Psalm 90/91:13, “Thou shalt tread upon the lion and adder.” An angel appears from above to grant crowns of victory to both martyrs.

Painting of St. George and St. Demetrius, Church of St. Nicholas, 1499, Balinesti (image: Vlad Bedros)

St. George trampling the monster, double-sided icon, 15th century, Neamt Monastery (image: Vlad Bedros)

The iconography of martyrs enthroned and/ or of martyrs trampling monsters was developed in Late Byzantine art. It first appeared in Moldova in the early 15th century, introduced by a double-sided icon at Neamț Monastery. The imagery was soon reiterated in frescoes and embroidery.

A similar influence of South-Eastern models is seen in the depiction of the two saints Theodore (Theodore the General and Theodore the Recruit), represented as a pair of figures in prayer.

This iconography was created at the end of the 13th century in the Balkan area of Kastoria and Ochrid but rarely encountered outside of that perimeter.

Saints Theodore the General and Theodore the Recruit, shown as a pair in prayer. St. Nicholas Church, 1499, Balinesti (image: Vlad Bedros)

Of the same Balkan origin is a peculiar episode from the cycle of the Passions, depicting Pontius Pilate mounted on a horse, assisted by other riders, all of whom were following the cortege leading Christ to crucifixion. Pilate is shown carrying, in his raised hand, the scroll containing the verdict that will eventually be affixed on top of the cross. In a uniquely Byzantine approach to this biblical narrative, the text is slightly altered: instead of “The king of Jews,” it reads, “The king of Glory.”

Known as the “Cavalcade of Pilatus,” this episode is depicted in almost all Moldavian wall paintings, which provides further evidence for the presence of Late-Byzantine Balkan-area workshops in Moldova since the late 15th century.

Pilate following Christ to crucifixion, painting from cycle of the Passions, St. Nicholas Church, 1499, Balinesti (image: Vlad Bedros)

Despite all these purely Late Byzantine traits, the paintings at Bălinești are not linked solely to the South-Eastern European tradition. They also show the clear influence of the Late Gothic style, which was pervasive in Northern and Western Europe. The golden stars stamped on blue backgrounds in a regular pattern, the ornamental bands of foliage in hues of dark brown, green, and ochre, the imitation of diamond-shaped polychrome stones, the rainbow motif used for the medallions encircling the portraits from the vault—all of these elements point to the lofty and courtly Late Gothic style. At the end of the 15th century, this style was still active in Central and North-Eastern Europe, areas with which Moldova sustained close political and economic ties.

Elements of Late Gothic style: ornamental foliage bands; imitation of diamond-shaped polychrome stones; and rainbow motif encircling medallion portraits of saints. 1499, Balinesti (images: Vlad Bedros)

This Gothic imprint is also present on a more profound level, subtly altering the Late Byzantine models through the inclusion of Gothic-style details. For example, in the conch of the sanctuary, the enthroned Virgin stands on a delicate Gothic-inspired bench that curves so as to follow the concavity of the vaulting.

Gothic-inspired furniture element in painting of enthroned Virgin, St. Nicholas Church, 1499, Balinesti (image: Vlad Bedros)

Also, the graceful silhouette of the martyr Procopius introduces a Gothic contrapposto in the otherwise typically Late-Byzantine portrayal of this saint.

For another example, the scroll held by saint Nicholas in the votive portrait whirls and bends, echoing the taste for whimsical details so strongly present in Late Gothic art.

Intersected traditions

The church of St. Nicholas in Bălinești epitomizes the strength of the “periphery” as agent of cultural innovation. Situated on the frontier between the Orthodox Post-Byzantine and the Western Late-Medieval worlds, the arts of the principality of Moldova adopted a hybrid visual identity, merging artistic practices from both sources.

Continuing research into identifying the agents of these transfers and the processes involved in this cultural hybridity will shed further light onto the visual entanglements so characteristic of Moldavian artistic production at the end of the 15th century and in the first half of the 16th century.