Church of the Annunciation, view from southeast, Moldovița Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1532–37 (photo: Nicu Farcaș, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Richly painted both inside and outside, the Church of the Annunciation at Moldovița Monastery is one of the best preserved churches of the early 16th century in the region of the Carpathian Mountains. It was built, decorated, and endowed with support from the local ruler, Prince Peter Rareș, between the years 1532 and 1537 in the former principality of Moldavia, which extended over the region of northeastern modern Romania and the Republic of Moldova. Moldovița is a prime example of how local church architecture in Moldavia developed at the crossroads of competing Latin, Greek, and Slavic traditions during the early 16th century.

![Aerial view showing Moldovița Monastery including additional structures and fortifications, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1532–37 (source: Tereza Sinigalia and Oliviu Boldura, Monumente Medievale din Bucovina [Bucharest: ACS, 2010], p. 171)](https://smarthistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Fig-1-1-300x336.jpg)

Aerial view showing Moldovița Monastery including additional structures and fortifications, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1532–37 (source: Tereza Sinigalia and Oliviu Boldura, Monumente Medievale din Bucovina [Bucharest: ACS, 2010], p. 171)

Moldovița’s architecture

At Moldovița, the main church, dedicated to the Annunciation of the Virgin, was built first at the center of the monastic compound, and the surrounding structures were later added. These included the cells of the nuns, the living quarters of the abbess, the princely house (now a museum), the treasury, and the refectory (or dining hall), with other auxiliary rooms and cellars below. The monastery was also heavily fortified in order to protect the community in times of conflict and set the monastic world apart from the rest.

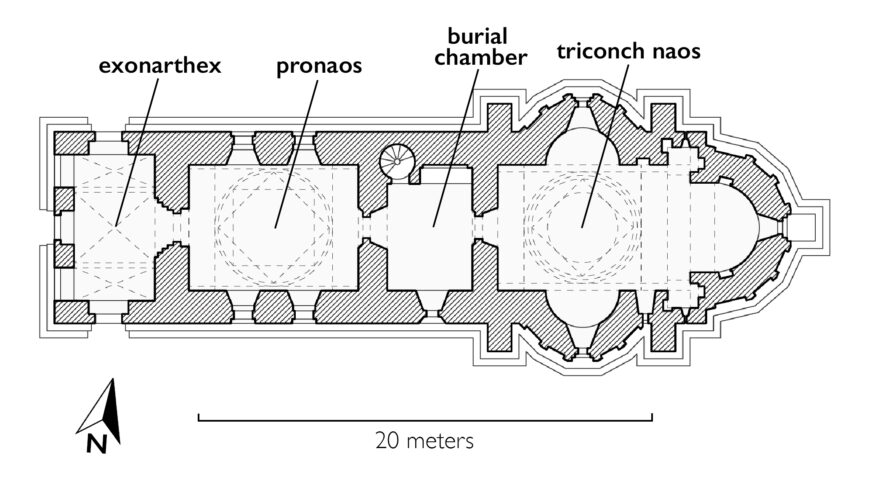

The church at Moldovița was built with local stone on a so-called elongated triconch plan. The layout of the church consists of an open barrel-vaulted exonarthex at the west end. A single narrow entryway leads into the domed rectangular pronaos of the church, which has two large windows on each of the north and south walls. This space, in turn, leads through another small entryway into a small barrel-vaulted burial chamber. The burial room leads to the triconch naos where the liturgical ceremonies are celebrated.

Plan for the Church of the Annunciation, Moldovița Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1532–37 (source: Richard Thomson)

The naos comprises a central rectangular space with two lateral semicircular apses, extending to the north and south, and a cylindrical tower above with four narrow windows pointing in the cardinal directions. Toward the church’s east end, the altar area, or chancel, is separated from the naos by a large iconostasis with painted icons in multiple registers. The layout, architectural features, and furnishings of the church at Moldovița offer a longitudinal progression of spaces of different dimensions that serve diverse functions. For the faithful advancing through the church, these spaces grow progressively darker as one approaches the altar area.

Eaves (detail), Church of the Annunciation, view from southeast, Moldovița Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1532–37 (photo: Frank Hukriede, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Built on a plan adapted from Byzantine models, the church at Moldovița also displays several Gothic features. The subdivisions of the roof, with steep slopes and large, smooth eaves following the undulating line of the apses, and the three-tier buttresses on the exterior, find visual parallels in Gothic buildings in neighboring Transylvania and Hungary. Furthermore, the door, window framings, and the window tracery derive from Gothic models. Although little information survives about the masons who worked at Moldovița, certain stonecutters active in Moldavia in the early 16th century were trained in Transylvanian workshops that generally followed Gothic building practices and designs.

Brightly colored murals inside and out

In addition to the distinctive architecture of the main church at Moldovița, the brightly colored mural cycles set in multiple registers on the interior and exterior walls of the building are another striking feature of the edifice. Executed by local and traveling artists, these murals display Christological, Mariological, and hagiographical stories interspersed with monumental images of historical and apocalyptic scenes, as well as full-length depictions of saintly figures and angels. Although the murals follow mainly Byzantine models, select iconographies derive from western medieval prototypes, and the inscriptions are all written in Church Slavonic, thus demonstrating the blending of distinct visual traditions in the Moldavian cultural context of the early 16th century.

Interior view of the pronaos, church of the Annunciation, Moldovița Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1532–37 (photo: Alice Isabella Sullivan)

On the exterior of the church, the mural cycles are best preserved on the south, west, and east sides; the north wall murals are most damaged due to local weather conditions. The south wall of the burial chamber received a monumental scene of the Tree of Jesse, which is an image type that traces the genealogy of Christ, and in particular his human lineage, through Jesse, his son David, the kings of the Old Testament, and then finally through the Virgin Mary. The representations of the Tree of Jesse highlighted the notion of lineage—that of Christ in the painted representation, and that of the noteworthy individual laid to rest in the space of the burial chamber beyond the painted exterior. As such, a holistic view of the image cycles reveals that they were carefully designed for each section of the building.

Exterior view of the south façade showing the Tree of Jesse and the Akathistos Hymn, church of the Annunciation, Moldovița Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1532–37 (photo: Alice Isabella Sullivan)

Next to the Tree of Jesse, the church’s south wall displays twenty-four scenes that illustrate the stanzas of the Akathistos Hymn. This is the oldest performed hymn dedicated to the Virgin Mary sung in the Eastern Christian Church. It celebrates the important events in the life of the Virgin, praising her role in the Incarnation, Redemption, and other mysteries. During the Middle Ages, the Akathistos Hymn evolved into a war hymn believed to bring divine protection to Constantinople in moments of struggle.

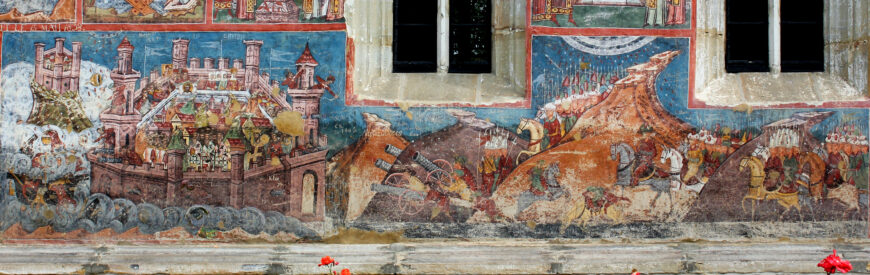

The Siege of Constantinople, exterior mural, south façade, church of the Annunciation, Moldovița Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1532–37 (photo: Alice Isabella Sullivan)

By the 15th century, the representations of the Akathistos acquired historical narratives. They were accompanied by a scene depicting the Siege of Constantinople saved through divine intervention. Moldovița preserves a particularly striking example. The mural does not reference a single historical event but several, augmenting the impact of the historical narrative. In particular, the mural conflates various triumphant victories of the Byzantine capital during the sieges by the Avars and the Persians in 626, by the Arabs in 717/18, and by the Rus’ in 860. The inclusion of contemporary artillery in the mural at Moldovița—such as the culverin cannons, Turkish spears, and halberds at the center of the composition—presents an anachronism that brings the relevance of these earlier victories into the present. In light of the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 and the ongoing Ottoman threat across Eastern Europe at this time, the image reassures that divine aid is forthcoming. The scene was painted on the exterior of several Moldavian churches at about eye level and close to the main entrance to the church, ensuring that its crucial message reached the faithful entering and leaving the church building.

Exterior view of the south side of the apse, church of the Annunciation, Moldovița Monastery, Moldavia, modern Romania, 1532–37 (photo: Sîmbotin, CC BY-SA 3.0 RO)

Finally, around the triconch apses of the church, five registers display figures arranged hierarchically, beginning with monks and hermits at the bottom, followed by martyrs, apostles, prophets, and angels. These figures are shown full-length. They direct their attention toward the east, as if partaking in a procession around the building that culminates at the axis of the altar window where Eucharistic imagery abounds, like Christ as the Lamb of God. These kinds of exterior images would have welcomed a circumambulation of the church in the context of certain liturgical ceremonies, such as those that occur even to this day during the Easter celebrations.

Moldovița Monastery demonstrates how local church architecture in the principality of Moldavia was informed by the region’s networked position relative to Byzantium, the West, and the Slavic cultural spheres in the post-Byzantine period. It also reveals the new and creative spatial and visual forms that developed in local church architecture as Moldavia assumed the role of a bastion of orthodoxy at the edges of empires and of Europe.