Raphael, The Transfiguration, 1516–20, tempera on wood, 405 x 278 cm (Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City)

When Raphael died in 1520, the Transfiguration was placed at the head of his bier inside the Pantheon in Rome. The artist’s last painting was immediately recognized as a masterpiece. [1] Though Raphael could not have known he would die at age 37 while finishing the altarpiece, the painting’s ambitious take on a traditional subject was always intended to cement his reputation as one of the great, if not greatest, artists of his era.

The Transfiguration and the possessed boy

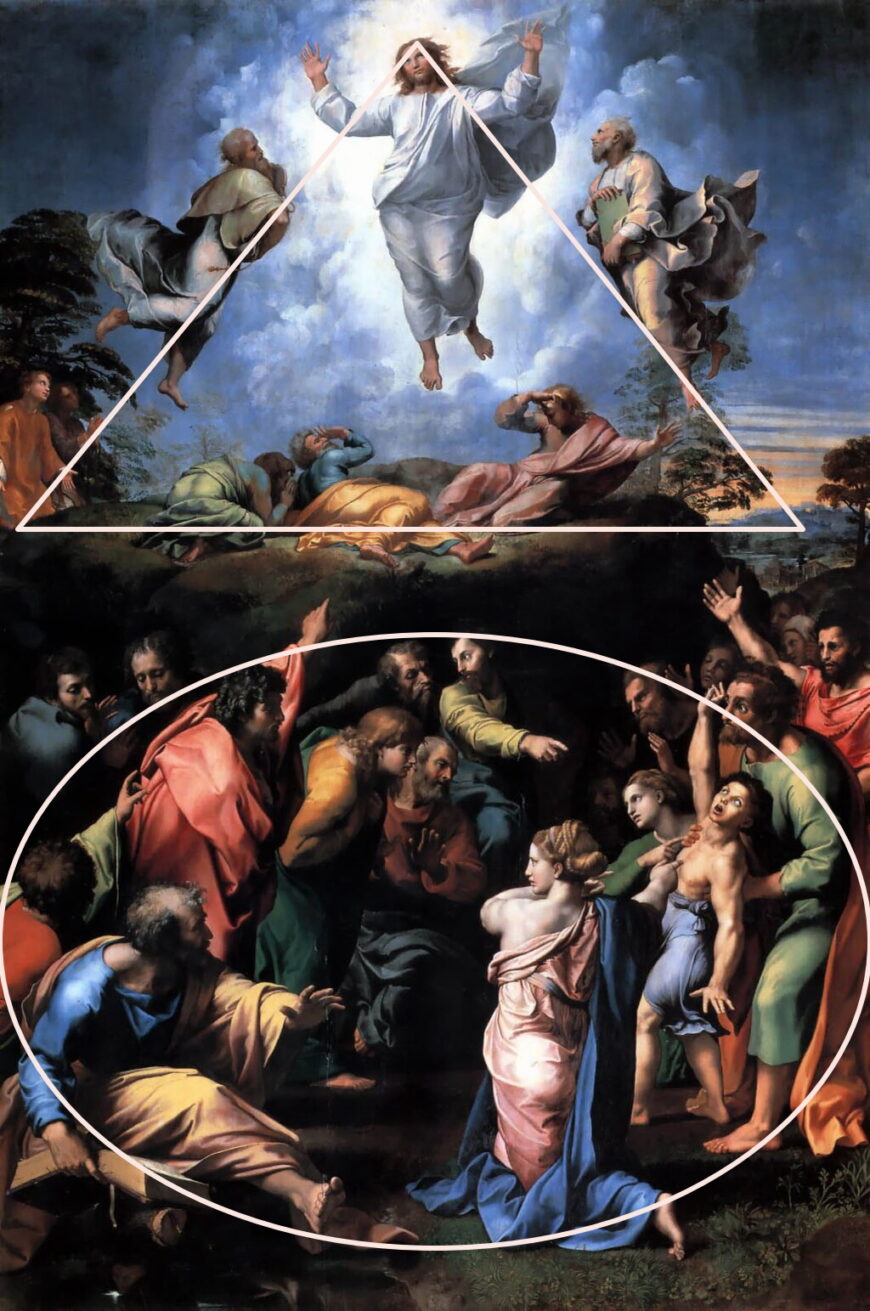

The Transfiguration oddly combines two stories that had not been presented together before. In the upper half of the composition, the altarpiece depicts the New Testament story of Christ’s miraculous “transfigured” appearance bathed in overpowering light. [2] The episode is typically understood as a revelation of Christ’s divine nature. Christ levitates above the entire painting, arms lifted in an orant prayer position. A light burst behind him shaped like a mandorla (an oval halo) illuminates the faces of Old Testament prophets Moses and Elijah who join him above the mountaintop. The apostles Peter, James, and John roused from their sleep shade their eyes from the intense brightness. They form the base of a triangle with Christ as its apex.

Raphael, The Transfiguration, 1516–20, tempera on wood, 405 x 278 cm (Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City)

In the lower half of the altarpiece, figures gesticulate frantically around a possessed boy half dressed in blue in an awkward twisting pose. A statuesque woman in pink and blue points to the tormented child presented by his parents in green. The nine remaining apostles attempt to heal the boy in vain. Their efforts are highlighted by dramatic tenebristic lighting bright against deep shadows. Only Christ, upon his return, will be able to heal him. Alone, the figures in the lower half of the painting form an oval. Together with the upper half of the painting, the figures, especially the arms extended up towards Christ, extend the pyramidal composition.

Sebastiano del Piombo, Pope Clement VII, c. 1531, oil on slate, 105.4 x 87.6 cm (J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles)

A competitive commission

Raphael’s altarpiece was guaranteed erudite scrutiny. Nobody less than Giulio de’ Medici, then a cardinal, cousin and advisor of Pope Leo X (and the future pope Clement VII himself), commissioned the altarpiece sometime before January 1517. The artwork intended for the Saint-Just cathedral in Narbonne would be a gift from the cardinal to the new bishopric in southern France he had acquired in 1515. The painting would demonstrate de’ Medici’s generosity and excellent taste in the latest developments in art.

Left: Raphael, The Transfiguration, 1516–20, tempera on wood, 405 x 278 cm (Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City); right: Sebastiano del Piombo, Raising of Lazarus, 1517–19, oil on wood transferred to canvas, 381 x 299 cm (The National Gallery, London)

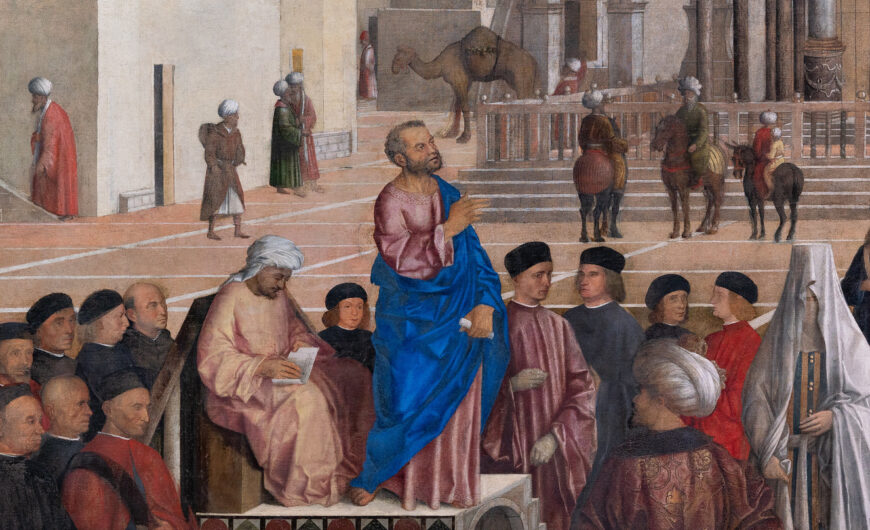

Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici elevated the stakes for Raphael by creating an implicit competition. He commissioned both Raphael and the painter Sebastiano del Piombo to create altarpieces that would be displayed together in the Narbonne cathedral. Sebastiano and Raphael had worked contentiously in the same room before at Villa Farnesina in Rome where Sebastiano’s sedentary fresco of Polyphemus sat next to Raphael’s exuberant Triumph of Galatea.

Left: Sebastiano del Piombo, Polyphemus, c. 1513, fresco; right: Raphael, Galatea, c. 1513, fresco (both, Villa Farnesina, Rome)

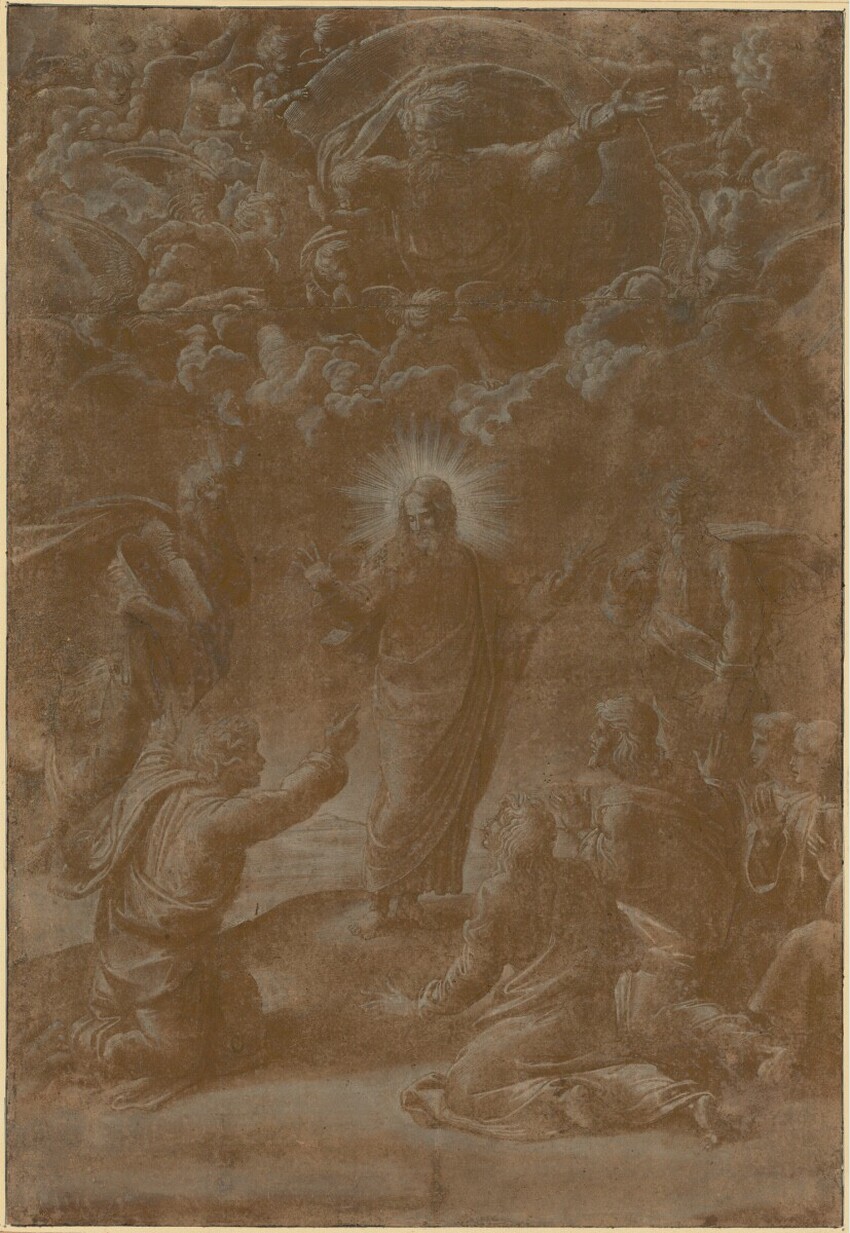

For the commission from Giulio de’ Medici, Sebastiano enlisted Michelangelo’s help to design the Raising of Lazarus. Raphael and Michelangelo had previously faced off in Rome with dueling commissions when Raphael painted the papal apartments, the “stanze,” beginning in 1508 while Michelangelo created the Sistine Chapel ceiling frescoes from 1508–12. Both artists knew their work would be compared. In this case Sebastiano’s monumentality lost to Raphael’s “unparalleled complexity” in the court of public opinion. [3]

Giulio Romano, Modello for the Transfiguration of Christ, c. 1518–19, pen and brown ink with white highlights on dark brown primed paper, 40 x 27 cm (Albertina, Vienna)

Left: Raphael, The Transfiguration, 1516–20, tempera on wood, 405 x 278 cm (Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City); right: Titian, Assumption of the Virgin, 1516–18, oil on panel, 690 x 360 cm (Basilica di Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, Venice)

Two stories in one altarpiece

The final double-narrative composition (with both the Transfiguration and the story of the possessed boy) continues the 16th-century trend towards narrative altarpieces, which previously had been dominated by static, devotional figures outside of a story (for example Fra Filippo Lippi’s Madonna and Child with Two Angels). Raphael’s Transfiguration follows Titian’s 1518 Assumption altarpiece and his own 1507 Deposition made for an altar in Perugia. Though the Transfiguration is characterized by a frenzy of action, Raphael lifted Christ’s arms in an orant position (similar to Titian’s Virgin in the Assumption) typical of non-narrative devotional imagery. The pose models what the worshipper should do and helps focus prayer. [5] Pairing two stories not previously linked to each other has spurred interpretations from countless writers over the centuries—including Goethe and Nietzsche.

While no one explanation for the paired stories of the possessed boy and Transfiguration has earned consensus, most art historians believe that the two stories present two sides of the same theme. For example, the Transfiguration miracle could refer to divine grace in contrast to the human failure to heal without divine grace below. [6] Given the rank of Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici and the prestige of the commission, it’s possible that the painting refers to more esoteric concepts such as Christus medicus, Christ the healer, or theories of spiritual vision. [7] What can and cannot be seen emerges as a theme. Figures insistently point in vain, trying to show others what they have seen.

Artistic achievement

Unexpectedly combining two New Testament stories demonstrated the intellectual creativity the Italian Renaissance typically associated with well-respected poets. Painters had increasingly made the argument that their work should be considered intellectual, higher status, rather than mechanical, lower status, labor. [8] To further bolster the painting’s intellectual credentials, Raphael also made compositional choices recommended by the famous 15th-century art theorist Leon Battista Alberti, author of the 1435 theoretical text On Painting.

Raphael, The Transfiguration (details), 1516–20, tempera on wood, 405 x 278 cm (Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City)

Raphael increased the perceived difficulty (difficoltà in Italian) of the painting by setting it at night, which allowed him to cast figures in sharp relief, enhancing their three-dimensionality (rilievo, Italian for “relief”). The sculptural quality of the figures would have been understood to Italian Renaissance viewers as a competition (paragone, Italian for “comparison”) of painting with sculpture (known to be Michelangelo’s favorite medium). By employing sharp draughtsmanship in complex poses Raphael asked viewers to compare his prowess in painting and what the medium could produce to sculpture and conclude that he had surpassed it.

Alberti also declared that paintings should have a high level of variety (varietà in Italian), which Raphael provides across the panoply of figural poses. The female figure kneeling in blue and pink drapery, who might represent Mary Magdalene (whose relics were held at the cathedral in Narbonne), is a tour-de-force of figural drawing. Her complex twisting pose is known as a figura serpentinata, a “serpentine figure.” Brighter than the gathered apostles, she serves as a transitional figure between the space of the viewer and the space within the painting. She thus serves as Alberti’s recommended “festaiuolo,” who showed viewers where to look. Raphael’s audience would have been aware of Alberti’s prescriptions for painting and noticed his adherence to them.

Cultural trophy

Raphael’s last painting continued his self-conscious efforts to establish his paintings as important enduring entries into art history. He was successful; the Transfiguration was frequently cited as one of the greatest paintings of all-time leading up to the 20th century. Raphael’s last painting never made it to Narbonne, however. Recognizing the painting’s quality and its historical importance, de’ Medici kept it in Rome, donating it for the high altar of San Pietro in Montorio. He sent a copy of the Transfiguration to Narbonne. France would briefly possess the original storied altarpiece from 1797–1816 when Napoleon insisted he take the painting as part of the Treaty of Tolentino along with one hundred other items from the papal collections selected to glorify Napoleon. The Louvre, stuffed with war booty taken by the military emperor, was named the “Napoleon Museum” during these years. The Transfiguration returned to Rome after the fall of Napoleon and now is on display permanently at the Musei Vaticani. [9]