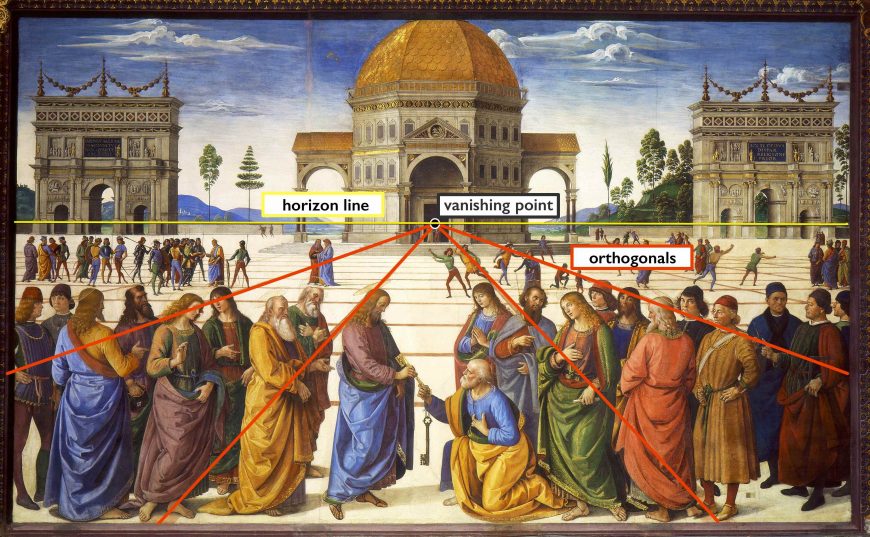

Perugino, Christ Giving the Keys of the Kingdom to St. Peter, Sistine Chapel, 1481–83, fresco, 10 feet 10 inches x 18 feet (Vatican, Rome)

In a fresco high on one wall of the Sistine Chapel, the aged Saint Peter kneels as he humbly accepts the keys of heaven from Jesus Christ standing before him. These two central figures are joined in the immediate foreground by a group of men to either side, some dressed in ancient styles, others in cutting-edge fifteenth-century fashion. They all have volumetric bodies that suggest gentle movement and expressions of solemn concentration. A wide piazza opens behind them, with figures and the piazza’s paving stones receding in scale to suggest a deep space. Forms on the distant horizon fade into an atmospheric haze. A massive building and two triumphal arches, set at even intervals in the background, convey a sense of balance and geometric solidarity.

Pietro Perugino’s biblical scene displays many of the key elements identified as necessary for a successful painting by Leon Battista Alberti in his treatise about painting, including:

- Convincing three-dimensional space

- Light and shadow to create bodies that look three-dimensional

- Figures in varied poses to create a compelling narrative

Alberti’s De Pictura (On Painting, 1435) is the first theoretical text written about art in Europe. Originally written in Latin, but published a year later in the Italian vernacular as Della Pittura (1436), this was the first artistic treatise to describe linear perspective and is the first known text in Europe to discuss the purpose of painting. Filippo Brunelleschi’s experiments in linear perspective had occurred earlier in the 1420s, but Alberti codified these ideas in writing. It was during his time living in Florence that Alberti developed his thoughts on painting as he interacted with artists such as Brunelleschi, Donatello, Lorenzo Ghiberti, Masaccio, and others.

Masaccio, frescoes for the Brancacci Chapel, 1427 (Santa Maria del Carmine, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

These artists experimented with linear perspective before Alberti wrote his text, as we see in Masaccio’s frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel or Donatello’s bronze The Feast of Herod. Alberti encountered first-hand works like Masaccio’s fresco cycle on the life of Saint Peter where biblical characters are convincingly three-dimensional, walk upon solid ground casting shadows, and interact emotionally to tell a story. He dedicated the Italian version of On Painting to the artists from whom he had learned his practical ideas. Alberti’s treatise was more ambitious than simply telling painters how to construct convincing three-dimensional space though. For him, painting “contains a divine force which not only makes absent men present . . . but moreover makes the dead seem almost alive.” [1]

Creating three-dimensional space

Know that a painted thing can never appear truthful where there is not a definite distance for seeing it.Alberti, On Painting, book 1:46

Alberti believed that good and praiseworthy paintings need to have convincing three-dimensional space, such as we see in Perugino’s fresco. In the first section of On Painting, he explains how to construct logical, rational space based on mathematical principles. It is here that he writes about linear perspective and how to construct a geometrically calculated vanishing point around which a painting’s composition is centered.

Perspective diagram, Perugino, Christ Giving the Keys of the Kingdom to St. Peter, Sistine Chapel, 1481-83, fresco, 10 feet 10 inches x 18 feet (Vatican, Rome)

A painting attributed to Luciano Laurana of an ideal city envisions Alberti’s ideas. The painting shows a perfectly symmetrical and mathematically defined cityscape. All of the forms within the painting appear to recede away from the viewer and converge at a single point at the center of the horizon line. By having a single vanishing point, Alberti was instructing viewers to look at a painting like The Ideal City as if it were viewed through a window frame.

Luciano Laurana (attributed), View of an Ideal City, c. 1475, oil on panel (Galleria Nazionale della Marche)

Making figures look real

There are some who use much gold in their istoria. They think it gives majesty. I do not praise it. Even though one should paint Virgil’s Dido whose quiver was of gold, her golden hair knotted with gold, and her purple robe girdled with pure gold, the reins of the horse and everything of gold, I should not wish gold to be used, for there is more admiration and praise for the painter who imitates the rays of gold with colors.Alberti, On Painting, book 2:83

Domenico Ghirlandaio, Birth of the Virgin, c. 1485-90, fresco, 24′ 4″ x 14′ 9″ (Cappella Maggiore, Santa Maria Novella, Florence)

For Alberti, the ultimate artistic goal of painting was to rival Nature in the depiction of visual reality. Forms within a painting should be modeled with light and shade to appear sculptural, as though they stand out from the two-dimensional surface like the forms in ancient relief sculpture. Domenico Ghirlandaio’s fresco depicting the birth of the Virgin Mary includes precisely the kind of convincing naturalism Alberti desired. In the scene, women cast shadows, and the deep folds and pleats in their dresses give the impression that their bodies take up space in the two-dimensional fresco.

Pietro Lorenzetti, Birth of the Virgin, c. 1342, tempera on panel, 6′ 1″ x 5′ 11″, for the altar of St. Savinus, Siena Cathedral (now in Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Siena)

Alberti also wanted human bodies to appear anatomically correct, and the movements and facial expressions of figures to suggest their emotions. The second part of Alberti’s treatise lays out these ideals, advising painters on how to most effectively tell a story (what he calls an istoria, or narrative) in their art using variety in figure types and gestures. Alberti wanted viewers to be able to relate to the stories portrayed in art and to empathize with painted characters, but he also wanted paintings to present an idealized vision of human behavior. In Ghirlandaio’s scene, women stand, kneel, or sit. Two women in the background lean toward one another to embrace. We also see how Ghirlandaio paints women looking in different directions to create a sense that they are interacting with one another, offering viewers a more compelling narrative than simply showing Saint Anne reclining in bed.

Painting as a liberal art

For their own enjoyment artists should associate with poets and orators who have many embellishments in common with painters and who have a broad knowledge of many things whose greatest praise consists in the invention. Alberti, On Painting, book 3:89

Why would Alberti go to such great lengths to talk about painting and its purpose? He wished for painting to be viewed as a liberal art, one similar to mathematics or music, rather than as manual labor. His goal was to elevate the status of painting, and painters along with it. One of the ways that he tried to prove that painting was an intellectual endeavor was to look to sources from antiquity. [2] He draws on the ideas of Roman authors such as Pliny the Elder, Quintillian, Cicero, Plutarch, and Lucian, turning to them for their discussions of ancient forms of painting and the artists who made them. He cites Pliny when talking about how artists like Praxiteles or Phidias were so skilled at painting that any work made by the Greek artists was valued more than costly materials like gold and silver. This inclusion and assumed familiarity with classical authors demonstrated his humanist learning and helped to initiate the formal transformation of the visual arts from manual skill to intellectual endeavor.

De Pictura encapsulates many of Alberti’s life pursuits. During his lifetime, he was a humanist, the author of an important architectural treatise, and a literary author who wrote plays, philosophical dialogues, and poetry in addition to working as a practicing architect and artist.

The reception of Alberti’s ideas

Despite the fame of Alberti’s ideas on painting today, this was not the case in his lifetime. Initially, On Painting was not printed—the European printing press wasn’t invented until around 1450. This means that Alberti’s ideas did not have a wide reception until later. Furthermore, renaissance artists would not have been able to read the 1435 Latin version of On Painting. Latin was the language of the educated elite, the language of the class of people who patronized art, not those who made it. It is likely that his initial intent was to share his ideas with a privileged audience, a reminder to us that artists worked at the pleasure of their wealthy employers. When he translated the text, he made it accessible to the people who might actually use his ideas directly.

Alberti’s ideas about painting influenced later generations of artists, including the giants of high renaissance art, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael. Even those who disagreed with Alberti’s ideas such as northern renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer, proceeded to write down their own ideas about perspective and painting.

René Magritte, The Human Condition, 1933, oil on canvas, 100 x 81 x 1.6 cm (The National Gallery of Art)

Alberti’s ideas would go on to have lasting influence on the history of art. Works of art by many early twentieth-century modern painters, such as Pablo Picasso’s Demoiselles d’Avignon, purposefully reject the illusion of deep space. They were avant-garde precisely because they challenged traditions of painting set in place since the time of Alberti. A painting like René Magritte’s The Human Condition also playfully engages with Alberti’s notion of a painting as a window through which a viewer perceives the world.

Notes:

[1] Alberti, trans. John R. Spencer, rev. ed. (1966), II:62

[2] While the Italian version differs in some respects from the Latin text, the translated work retains the classical references found throughout the Latin version.

Additional resources

Learn more about Alberti as an architect

Virtually explore the Papal Palace and the Sistine Chapel with Smarthistory as your guide

Check out Alberti’s On Painting