Raphael, School of Athens, fresco, 1509–11 (Stanza della Segnatura, Papal Palace, Vatican; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Why study Italian renaissance art?

Even if you are not a student of art history, you are likely familiar with the names Donatello, Leonardo da Vinci, Raffaello Sanzio (Raphael), and Michelangelo Buonarotti. There is a reason these names continue to be part of our contemporary popular culture (and it’s not just because these are the names of everyone’s favorite martial arts mutant Turtles). These artists were central to what we today call the Renaissance—a period in European history (c. 1400–1600) when some of our current ideas about society, politics, and art took form.

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between

Navigating the art of the past requires a different set of tools than those required for understanding art produced in our contemporary world. This introduction will orient you to some important, basic information as you begin to study Italian renaissance art. Within each section below you will find links to essays and videos that flesh out the themes introduced.

Michelangelo’s famous nudes on the Sistine Chapel ceiling borrow from ancient Roman art forms, such as the so-called Belvedere torso. Left: Apollonios, Belvedere Torso, a copy from the 1st century B.C.E. or C.E. of an earlier sculpture from the first half of the 2nd century B.C.E., marble, 159 cm (Museo Pio-Clementino, Vatican; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0); right: Michelangelo, Ignudo (detail), ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, Vatican City, Rome, 1508–12, fresco

The term “renaissance” is often used to designate a rebirth of interest in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds (often referred to as “classical antiquity”) that arose in Europe in the later Middle Ages.

While engagement with the Greco-Roman past was not new, it took on a new urgency in Italy beginning in the 14th century and was eventually felt throughout the European continent. This interest prompted new intellectual investigations (learn about humanism) that had a profound influence on European culture, affecting all realms of life including the visual arts.

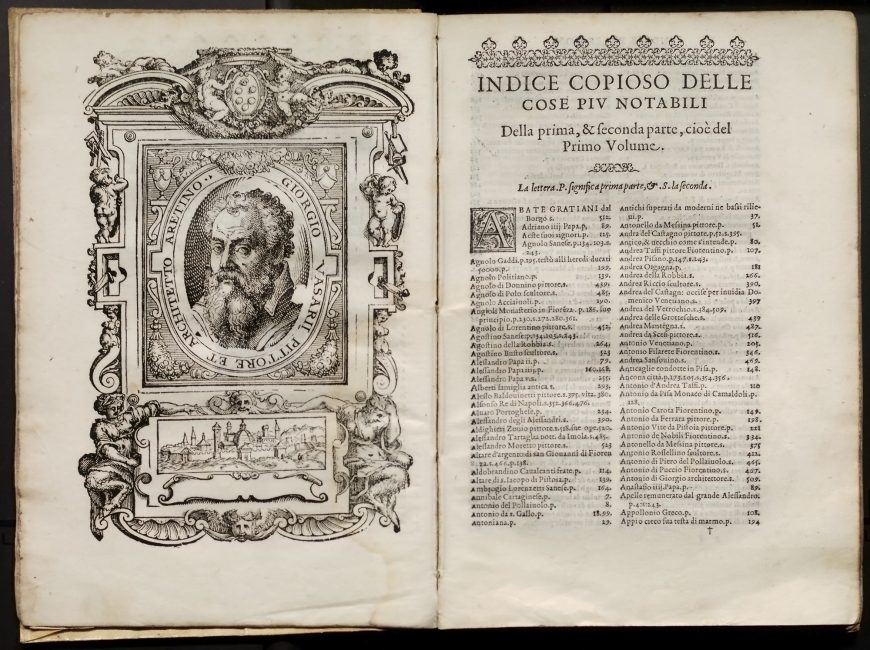

Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ piu eccellenti pittori scultori e architettori (Florence, 1568) (National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.)

Many of the artistic traditions originating or maturing in this context informed the direction of European art for the next several centuries. Linear perspective, volumetric figures rendered with anatomical precision, emotionally charged expression, and visual naturalism are formal elements popularized in the Renaissance. This was especially true of art in Italy where ancient Roman art demonstrating many of these traits was abundant (such as Roman relief sculpture and architecture).

This was also the period when artistic theory and the European discipline of art history began to develop. Leon Battista Alberti’s treatise, On Painting (1435/36), was the first theoretical text written on visual art in Europe and Giorgio Vasari’s Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550, 2nd edition 1568) was the first critical history of European art. Many of the ideas originating in the writings of these men and their contemporaries are still fundamental to artistic theory and practice today. In fact, Vasari’s categories of artists, including his privileging of Florentines, and standards for evaluation of their work have dominated the discipline. For several centuries after his text’s publication, the artists and visual approaches that he celebrated were seen as the “gold standard” in art, the foundation for what we call the European canon. Contemporary scholars striving for a more inclusive art history have worked to unpack and complicate Vasari’s ideas. His construction of the artist as a born genius, for example, an idea epitomized in his life of Michelangelo, has been repeatedly challenged in feminist scholarship. Privileges of sex, race, and social status enabled the artistic success that Vasari presented as inevitable.

Who?

To understand the art of the Italian renaissance, we need to consider the values, social mores, and the religious and political interests of the people who made, paid for, and first looked at the art. Unfortunately, our knowledge of these people is limited and skewed. History is most often written by those in positions of privilege and power who generally leave behind the most evidence of their lives and ideas. This means that we have quite a bit of information about some people—primarily Christian men who were wealthy merchants, educated elites, or members of the Church—and little to none from other social groups, including most women, the peasantry, non-Christians, and non-Europeans.

Raphael’s serene and pensive sitter is a far cry from the reality of the man depicted: the fiery Warrior Pope, Julius II. Even Raphael, the artistic darling of early 16th-century Rome, was far removed from his powerful patron’s exalted status. Raphael, Portrait of Pope Julius II, 1511, oil on poplar, 108.7 x 81 cm (National Gallery, London; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

With few exceptions, artists did not enjoy the status of intellectuals or social elites. Because they made things by hand that they then sold for profit, they were deemed of lower social stature than the wealthy merchants and aristocrats who bought their work. Art making was traditionally seen as a Mechanical, and not a Liberal Art (art of the mind). While the status of the artist did improve over the course of the Renaissance—thanks in part to our Ninja Turtles’ namesakes—it was a slow and uneven process. Most artists came from what we might call urban, middle-class roots and trained for a long period in a workshop, learning their craft rather than receiving the kind of Liberal Arts education available to members of the upper classes. Even though art theorists like Alberti argued for an artist’s education in a range of subjects including philosophy (which included “natural philosophy” or science), poetry, mathematics, medicine, and geometry (to name just a few), access to this education was limited. This changed somewhat in the 16th century with the rise of the first art academies, although the extent to which an artist could receive the kind of extensive education deemed ideal was still limited. Such advanced training was reserved for the sons of the elite. Even Leonardo da Vinci, the so-called universal genius (perhaps one of the few figures in history to whom that problematic title may justly be applied), was outside the world of highest learning, never having mastered Latin.

Despite the challenges facing Italian artists in participating directly in renaissance intellectual culture, many fought vigorously to elevate the status of their profession and their own corresponding social standing. Some artists, like Leonardo, sought to elevate visual art by drawing comparisons to philosophy or poetry. As he noted:

Painting is mute poetry and poetry is blind painting.

Leonardo da Vinci, Paragone [2]

They argued that despite making objects by hand, the renaissance artist’s practice was guided first by the intellect—like a poet or a philosopher. Such arguments were modeled on the writings of ancient Roman authors like Pliny, Lucian, and Cicero, another example of humanism at work.

As humanist-inspired tastes in art developed over the course of the early renaissance, so too did requirements for artists’ skills. Art making became increasingly professionalized. To develop the mathematically defined spaces populated by anatomically correct figures enacting complex narrative scenes from religious and classical history that were in vogue, artists needed to study geometry and anatomy. They had to read ancient texts in translation and consult with learned advisors, develop sophisticated preparatory studies, and negotiate business contracts. They also needed to navigate complex social relationships requiring savvy interpersonal skills.

As in most occupations at the time, it was not only social class, but also gender that determined artistic identity: artists were almost entirely men and art making was thought to be a male prerogative. The professionalization of artistic practice that helped raise the social status of art making had the negative effect of excluding women who, particularly in mercantile cities like Florence, were increasingly regulated to the domestic sphere. Although some female artists did achieve renown (such as Sofonisba Anguissola), their numbers were few until well into the 17th century.

This dazzling altarpiece reflected the magnificence of its patron, Palla Strozzi, the wealthiest man in Florence at the time of its creation. Gentile da Fabriano, Adoration of the Magi, 1423, tempera on panel, 283 x 300 cm (Galeria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

You have likely run across the name Michelangelo, but are perhaps less familiar with his great patron, Pope Julius II. This tells us more about our present-day fascination with artists than it does about the realities of the renaissance past. In this world, the patrons—the people who paid for (commissioned) the art work—were more socially privileged than the artists who worked for them and received much of the credit for the artwork they sponsored. Again, men were the primary patrons although some women in positions of special privilege like Isabella d’Este (marchioness of Mantua, a small but glamorous principality in northern Italy) commissioned art as well. There were many reasons for commissioning art. Art could advertise an individual’s learning and taste, wealth, and position, and even political loyalties and religious faith. Patronage ranged across media and genres and was commissioned for a variety of contexts including public piazzas, private homes and palaces, private chapels and tombs in public churches, and other sacred spaces.

Giovanni Bellini, San Zaccaria Altarpiece, 1505, oil on wood transferred to canvas, 16 feet 5–1/2 inches x 7 feet 9 inches (San Zaccaria, Venice; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

What?

I have repeatedly used the word “art” so far in this essay. To us, the paintings, sculptures, buildings, tapestries, prints, and other aesthetic objects created during this time are considered “art,” but this was not the case for people living during the Renaissance. The objects and images that we study as renaissance art were understood to be functional aspects of visual culture. The primary goal was not aesthetic appreciation or art for the sake of art, which is a category of experience that is a 19th-century invention. An altarpiece that may be viewed in an art museum today originally functioned as an object of devotion; it would have been the centerpiece of Christian religious practice in a sacred setting and was first and foremost a didactic tool guiding Christians in their worship. A portrait was a form of commemoration, a way to manifest a sitter’s presence when absent or to communicate family connections. Scenes drawn from ancient poetry or heroic tales were methods of communicating virtue, demonstrating erudition, and encouraging learned discourse. Were these images and objects appreciated as aesthetically interesting, even “beautiful”? Absolutely. But it’s important to note that this was not the primary goal.

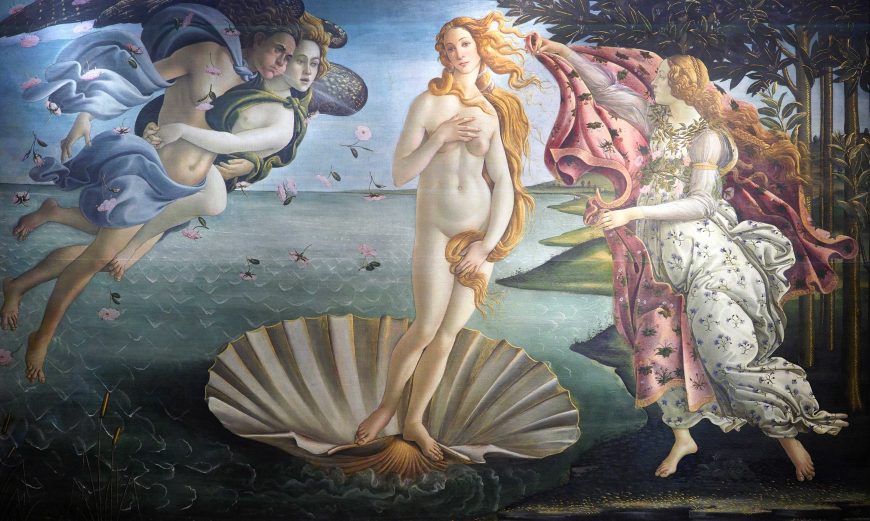

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus, 1483–85, tempera on panel, 172.5 x 278.5 cm (Galeria degli Uffizi, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

In renaissance art you will confront two main categories of iconography, or subject matter: secular (non-religious) and religious. Both types fulfilled different functions, but they also sometimes overlapped. Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus, for example, exemplifies secular iconography and borrows from ancient tradition. At the same time, Venus was associated with ideas about divine love circulating in late 15th century Neoplatonic philosophy, which (among other things) sought to reconcile ancient philosophy with Christianity.

Donatello, David, c. 1440, bronze, 158 cm (Museo Nazionale de Bargello, Florence; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

We also have two main categories of audience: public and private, which also often overlapped. Donatello’s bronze David was both a private artwork, placed within the powerful Medici family’s palace courtyard, and a public statement of their power, wealth, and faith—the work was visible from the street.

The Gathering of Manna, 1595–96 (Florence), designed by Alessandro Allori, Woven in Medici workshop under the direction of Guasparri di Bartolomeo Papini, wool and silk, 426.7 x 447 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York)

It is also helpful to be conscious of how the present-day media hierarchy is skewed to our own interests. While we tend to prioritize the arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture, what was valued in the past was different from what we emphasize in our current patterns of collection and display. Tapestries, for example, are not often on view in museums in significant numbers nor are they foregrounded in histories of art, in part because of the fragile nature of their medium (silk and wool thread does not survive the ravages of time as well as marble or brick), but also because the art form went out of style in the modern era. During the Renaissance, however, tapestries were one of the most prized forms of visual art. These spectacular creations were amongst the most sought after and costly objects, adorning the walls of palaces, churches, and government buildings across Europe. When learning about renaissance art you will encounter painting, large-scale sculpture, and architecture, but it’s important to note that this visual world also included—and sometimes more importantly—tapestries, vestments, liturgical objects, small-scale sculptures, prints, ceramics, embroidery, and other works. Our modern interests have shaped what we consider to be “great” art, or what is even considered worthy of study. These biases towards certain media, genres, and artists are our own—or those that we have been taught—not necessarily those of people throughout history, and it is helpful to be conscious of the distorted views of the past that they can sometimes create. Recent scholarship has worked to be more inclusive, increasingly exploring visual production in various media and broadening our definitions of just what constitutes “art.”

When?

When trying to delineate the period known as the “renaissance” scholars generally designate the years 1400–1600. I say “generally” because life doesn’t unfold in tidy demarcated centuries. Starting points are hard to determine. Developments in art and culture in the 1400s come out of those in the preceding centuries, including historical crises like the Black Death. Many surveys of so-called renaissance art, for example, start with the innovative creations of Giotto di Bondone who lived c. 1267–1337, which is often called the Late Middle Ages by us today. Would we have Beyonce without Aretha Franklin? The operas of Lin Manuel Miranda without Mozart? Similarly, why end at 1600? In a certain sense, all such delineations are arbitrary (did 5th-century Romans know that Rome fell?). We go by broad patterns and general trends. The European political, social, and religious landscape changed dramatically in the last few decades of the 16th century, due in no small part to the rise of Protestantism, and art changed with it making this a viable, if imperfect, end point.

From Petrarch, renaissance Italians inherited the notion of three distinct ages of man: what he saw as the glorious ancient past, the “dark ages” after the decline of the Roman empire, and his own modern age where the glories of antiquity were reborn. While this periodization of history is deeply problematic—we no longer recognize the period after the decline of Rome as a “dark age”—we still borrow this general framework, using terms like “antiquity,” the “middle ages,” and “the renaissance.” The following general—and admittedly imperfect—breakdown of historical periods is what most people mean when they designate these eras:

- 600 B.C.E.–400 C.E. Ancient Greece and Rome (also known as the classical past or classical antiquity, this 1,000 year span of time is itself broken by historians and art historians into smaller designations, such as archaic, high classical, hellenistic, etc.)

- 400–c. 1400 the Middle Ages (c. 1200–1400 is often called the Late Middle Ages)

- 1400–1600 the Renaissance

Where?

Italian renaissance art was made in Italy, right? Well, sort of. It was made on the peninsula in southern Europe that we call Italy today. But it wasn’t “Italy” then. The country was not united as we know it until the 19th century. During the renaissance, the Italian peninsula was organized into independent city-states with distinct political and social formations as well as unique dialects and cultural traditions. Some states, like Florence, Venice, and Genoa, functioned as republics where members of the urban elite governed by election. Others, like Milan, Ferrara, and Urbino, were governed by a sovereign, a ruler who had almost absolute hereditary authority. These Signorie or Lordships were usually under the leadership of a Marquis or a Duke and technically owed their allegiance to a superior political power—some were granted authority by the Holy Roman Emperor, some from the Church. In practice, however, these ruling princes (a catch-all term used throughout the Renaissance to designate a ruler), enjoyed virtual independence. There was also a massive swath of central Italy that came under the direct rule of the Catholic Church—led by the Pope—a region known as the Papal States. The southernmost part of the peninsula was divided into the Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily which were ruled by a series of dynasties throughout the Middle Ages until finally unified under a single king (ranking just below an Emperor), in the 15th century by the Spanish House of Aragon. Throughout the renaissance period, Spanish and French royal families vied for power in this territory. While we may discuss “Italian renaissance” art broadly, and there were certainly shared religious and social values as well as a shared ancestry with the ancient Roman past across the peninsula, it is important to understand that this was not a unified state in our modern sense. In fact, these various territories were often at war with one another.

Gentile Bellini, Portrait of Sultan Mehmet II, 1480, oil on canvas, 69.9 x 52.1 cm (National Gallery, London)

This was a permeable and highly international world. Contacts with different peoples and cultures were common. This was an age of international trade (including the slave trade), exploration, rising colonial enterprises, and war, all of which required deft diplomacy. Venice, for example, was a maritime trading power that held vast territories in the north Italian mainland and throughout the Mediterranean world, and as a result had large populations of foreigners. Greek influence was particularly strong there due to the city’s colonies in Crete, Cyprus, and Rhodes, and became more so with the influx of Greek immigrants to the region after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453. Italian artists traveled throughout the Italian peninsula working for different patrons and in variable contexts; as they moved about so too did the various indigenous visual traditions in which they were trained.

Artists also went beyond Italy, finding work in the urban centers and courts of other European states and beyond. The painter Gentile Bellini spent fifteen months at the court of the Ottoman Sultan, Mehmed II as representative of the Venetian Republic. Likewise, artists from other parts of the world came to Italy. Some, like Albrecht Dürer and Alonso Berruguete, helped transform art across the continent by introducing new approaches that fused Italian traditions with those developing elsewhere. Other Italian artists even relocated to the Americas or Asia, such as those associated with the Jesuit missionary order.

But still, why do renaissance art history surveys so often start here in this region that wasn’t Italy but we all call Italy? It was in this region that many of the developments that are understood to have informed the rise of something new—what we call a “renaissance”—first emerged. The Italian city-states were early to urbanize and enjoyed relative political and economic stability, key ingredients to the creation of vast amounts of art and architecture. That literary and visual forms emerge reflecting new “renaissance” styles in these states was also a direct function of the force of the visible presence of the ancient Roman past—in Italy Rome was everywhere, in texts preserved in monasteries and libraries of the Middle Ages, and in the copious remains of visual art and architecture.

Notes:

[1] See for instance the art historian Linda Nochlin’s canonical essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” ARTNews, volume 69, number 9 (1971), pp. 22–39, 67–71.

[2] Quoted in André Chastel, The Genius of Leonardo da Vinci: Leonardo da Vinci on Art and the Artist, translated by Ellen Callmann (New York: Orion Press, 1961), p. 38. Leonardo was looking to Plutarch: “Painting is mute poetry and poetry a speaking picture,” in Plutarch, Moralia (1819), p. 346.

Additional resources