El Greco, Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586–88, oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm (Santo Tomé, Toledo, Spain)

A miracle at a burial

Don Gonzalo Ruíz, who died in 1323 (and was later known by the title, Count of Orgaz), is not likely someone you know. Ruíz, who was the Señor (Lord or ruler) of the town of Orgaz, donated money to the church of Santo Tomé in Toledo, Spain upon his death. Local stories circulated about the Count of Orgaz in the fourteenth century, including a miraculous story of the circumstances of his burial: that after he died Saints Augustine and Stephen lowered him into his tomb to honor him for his good deeds. This story continued to be popular in the city of Toledo, serving as the source of inspiration for one of the city’s most famous paintings: El Greco’s The Burial of the Count of Orgaz. The painting was made for the burial chapel of the Count of Orgaz at Santo Tomé between 1586 and 1588. While you may not know Don Gonzalo Ruíz, chances are you’ve seen a reproduction of El Greco’s painting—it is one of the world’s most recognizable and often reproduced paintings.

“The Greek”

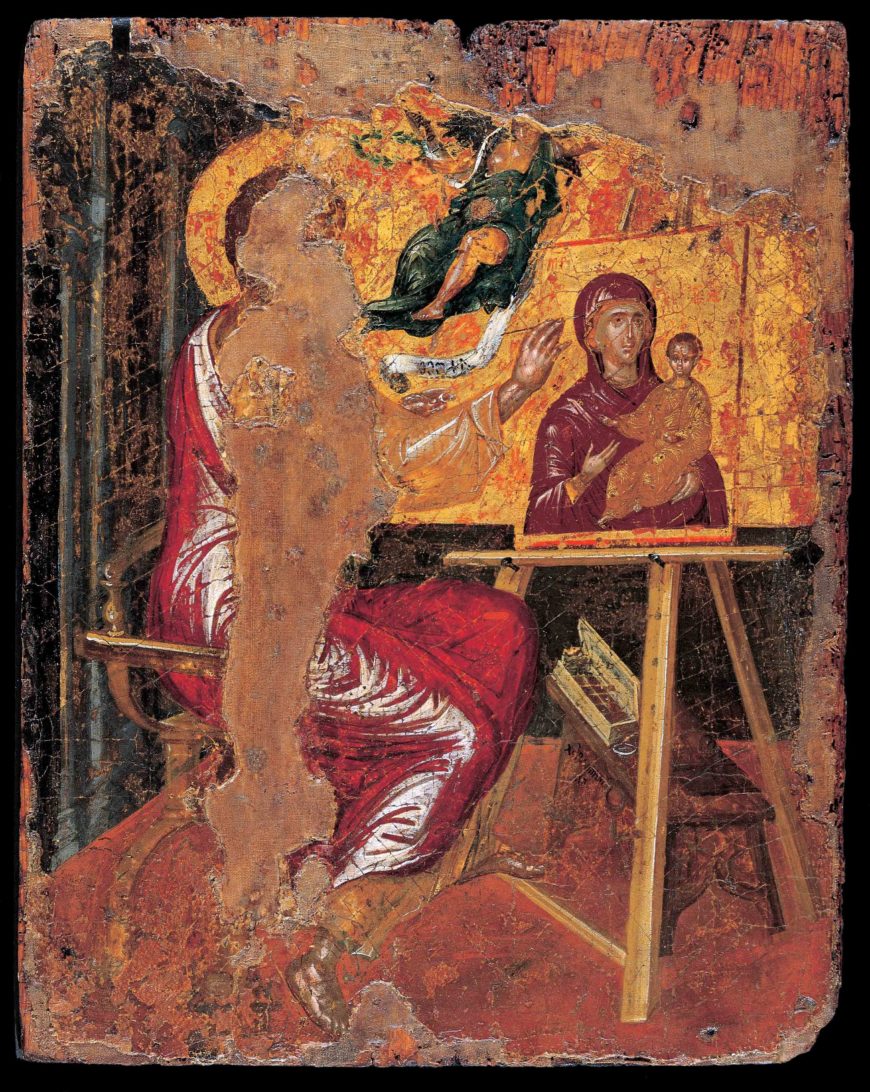

El Greco, St. Luke Painting the Virgin and Child, c. 1560–67, tempera and oil on panel, 41.6 x 33 cm (Benaki Museum)

El Greco (Domenikos Theotokopoulos), or The Greek, is known for numerous paintings where malleable and elongated figures are lit from sources that can’t readily be discerned. Born and raised in Crete, El Greco was trained as a Greek icon painter (in a post-Byzantine style). At the time he painted on Crete, Venice controlled the island. He left for Venice at age twenty-six, where he worked in Titian’s workshop and was influenced by Tintoretto’s loose brushwork.

He then traveled to Rome before settling in Toledo, Spain in 1577 to work for the Spanish King Philip II. He lived there until his death in 1614. Some of his contemporaries, like Friar Hortensio Félix Paravicino, commented on how his time in Toledo gave him his remarkable artistic abilities, “Crete gave him life, and Toledo his brushes….”¹ After his death, El Greco continued to inspire artists, including twentieth-century avant-garde artists like Pablo Picasso, who found inspiration in El Greco’s fluid distortions of the body.

The painting

El Greco’s Burial of the Count of Orgaz is monumental—more than 15 feet high—and depicts numerous figures in addition to the miraculous circumstances surrounding the burial of Don Gonzalo Ruíz.

Burial (detail), El Greco, Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586–88, oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm (Santo Tomé, Toledo, Spain)

At the bottom center, Saint Augustine (on the viewer’s right) and Saint Stephen (on the viewer’s left) hold the Count of Orgaz, who is dressed in armor. As they lower him into his tomb, we get the impression that they place his body into the physical tomb that exists in front of the painting in the burial chapel.

Titian, The Entombment of Christ, c. 1520, oil on canvas, 148 x 212 cm (Louvre, Paris)

This act is reminiscent of paintings showing the entombment of Christ, such as versions by Raphael or Titian, where Christ’s body is lowered into its grave. Perhaps El Greco adapted this subject for his painting to emphasize the solemn moment and the miraculous nature of the burial itself.

Earthly scene (detail), El Greco, Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586–88, oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm (Santo Tomé, Toledo, Spain)

Here on earth

Other religious figures in the lower scene include Franciscan, Augustinian, and Dominican friars. The parish priest of Santo Tomé, Andrés Núñez de Madrid (shown reading, far right), and other individuals who lived in late sixteenth-century Toledo are visible. The men dressed in black and decorated with red crosses belonged to the Order of Santiago (St. James the Greater), an elite military-religious order.

El Greco, Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino, 1609, oil on canvas, 112.1 x 86.1 cm (The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston)

El Greco’s young son, Jorge Manuel, stands to the left of St. Stephen and points towards the saints lowering Orgaz’s body, leading our eye to the main subject. The figure directly behind and above Saint Stephen who looks out at viewer is a self-portrait. While El Greco was an accomplished portrait painter, as evidence by his painting of Friar Hortensio Félix Paravicino, the Burial of the Count of Orgaz is remarkable for the number of portraits included within such a complex composition.

It was customary for elite men to come to the burial of other nobles in Spain at this time, but why would El Greco include so many of his contemporaries in a painting ostensibly focused on a miraculous story about the Count of Orgaz? The answer can be found in the painting’s 1586 contract that stipulated that portraits be included to suggest that they witnessed the miracle. El Greco brilliantly combines portraits with saintly figures—the spiritual with the historical. Santo Tomé was El Greco’s parish church, so he likely included people he knew in the painting as a sign of respect.

St. Stephen’s clothing (detail), El Greco, Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586–88, oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm (Santo Tomé, Toledo, Spain)

To help people feel like they were among their contemporaries, El Greco emphasized the naturalistic textures of the clothing, the reflective shine highlighting the metal armor, and even the faces and skin of the individuals in the earthly realm. Saint Stephen’s vestments are so detailed that we can see a scene of his martyrdom on the lower edge. Yet for all the naturalistic elements of this lower scene, it still seems mysterious. Are we outside at night? Are we inside the chapel? It is unclear. Nevertheless, the dark atmosphere heightens the sense of mourning and drama of the painting.

Just like heaven

The heavenly realm covers the upper half of the composition. We see many figures here as well, including both angels and saints—David with his harp, Peter with his keys, John the Baptist, the Virgin Mary, and Christ. The Spanish King Philip II and Pope Sixtus V are also visible in this celestial realm.

Between Mary and Christ, an angel guides the Count of Orgaz’s small soul (what looks like a baby) upwards (a gesture common in Byzantine icons generally). The Count’s soul will be judged by Christ in Heaven, who presides over the entire scene. Anyone looking at the painting was reminded that judgment awaits them too.

Heaven (detail), El Greco, Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586–88, oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm (Santo Tomé, Toledo, Spain)

Heaven and earth

El Greco’s style differs between the two realms. In the upper heavenly realm, the artist used looser brushwork to give the figures a more ethereal and dynamic quality. He also chose cooler colors, including silvers and lilacs, that appear to shimmer and reflect light. The lower half of the canvas has a darker, more earth-tone palette (except saints Stephen and Augustine), giving it a more naturalistic appearance. Differences also exist between the way the figures in each realm are painted. Christ, Mary, and John the Baptist are more angular and elongated than those below. These figures are often described as dematerialized—less material or solid. We certainly get this impression from some of the wispy, insubstantial figures among the clouds.

Earthly scene (detail), El Greco, Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586–88, oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm (Santo Tomé, Toledo, Spain)

We get the sense of a solid group surrounding the burial of Orgaz. The figures are arranged as a frieze that moves across the bottom half of the painting with the heads forming a straight horizontal line, giving an impression of stability.

This differs from the heavenly realm, where the clouds arc upwards to creates a sense of motion and flux. These clouds and the way that El Greco uses them to define clusters of figures at differing heights helps to remove the heavenly realm from reality and to provide a sense of motion that contrasts with the more static scene below.

Heaven (detail), El Greco, Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586–88, oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm (Santo Tomé, Toledo, Spain)

El Greco, Burial of the Count of Orgaz, 1586–88, oil on canvas, 480 x 360 cm (Santo Tomé, Toledo, Spain)

Even though the celestial and earthly realms are divided, El Greco links them to create a unified painting. Staffs and torches held by men on earth rise upwards, crossing the pictorial threshold between heaven and earth. Figures gaze upwards to heaven, encouraging us to lift our eyes as well. Certain figures also echo one another across the threshold of the two spheres. Mary and John the Baptist gather at Christ’s feet, leaning inwards—not unlike saints Stephen and Augustine holding the Count of Orgaz’s body.

Counter-Reformation artist

The mid-to-late sixteenth century was the era of the Counter Reformation, with Toledo as a staunch bastion of Catholic Christendom. At the Council of Trent (1545–63), the importance of saints as intercessors was defended in the wake of Protestant attacks. El Greco’s painting, made only two decades later, with its depiction of saints in both the earthly and heavenly realms, strongly reaffirms the spirit of the Counter Reformation and beautifully captures El Greco’s ability to pair the mystical and the spiritual with the life around him.

1. Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino y Arteaga, Obras posthumas, divines y humans (1641)

Additional resources:

Learn about the renaissance in Spain

Church of Santo Tome, Toledo (includes video in Spanish)

El Greco on The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Xavier Bray, El Greco (New Haven: Yale University Press and National Gallery Company, London, 2003).