Bellini imagines Saint Mark preaching in a collage of different times and places: ancient Alexandria, 16th-century Venice, and the Ottoman Empire.

Gentile Bellini (completed by Giovanni Bellini), Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria, 1504–07, oil on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (Brera Pinacoteca, Milan). Speakers: Dr. Beth Harris and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:06] We’re in the Brera, in the city of Milan, looking at an enormous canvas. It’s just overwhelming in its scale and its specificity. This is by the great Venetian painter Gentile Bellini. The painting is a kind of collage of different times and different places.

Dr. Beth Harris: [0:24] The thing that draws me to this painting is the fabulous architecture. It looks like a take on so many different famous buildings. It might remind us of Hagia Sophia, the church in Constantinople. It also reminds us of the great church of Saint Mark in Venice.

Dr. Zucker: [0:42] It’s meant to actually represent the Temple of Serapis in the city of Alexandria in Egypt. According to legend, Saint Mark preached the message of Christ on the site of the Temple of Serapis, an ancient fertility god. That temple was eventually transformed into a Christian church.

Dr. Harris: [1:00] Saint Mark is one of the most important figures in Christendom. He’s one of the four authors of the gospels.

Dr. Zucker: [1:08] In fact, Saint Mark is the patron saint of the city of Venice.

Dr. Harris: [1:13] Saint Mark is ultimately martyred, killed in Alexandria. His body is buried, and centuries later, Venetian merchants steal Saint Mark’s body from Alexandria and bring it back to Venice. A church is built, a place to house his relics. This ultimately becomes the Basilica of Saint Mark’s.

[1:35] Saint Mark himself is the key to, in some ways, the identity and the success of the Republic of Venice. Saint Mark, wearing this beautiful blue robe, and he’s standing on a podium speaking, but when Mark was in Alexandria, he was preaching to pagans. Here we see him in the Muslim world of the eastern part of the Mediterranean.

Dr. Zucker: [2:00] Mark didn’t live when there was such a thing as Islam, so this painting is out of time. It is a collage of different periods and of different architectural styles.

Dr. Harris: [2:10] Bellini is locating us firmly in Alexandria. For example, the column that we see in the background was a known feature of Alexandria. Another landmark that we see is the obelisk. This was brought to Alexandria by the Roman Emperor Augustus.

Dr. Zucker: [2:27] Then we see the minarets, presumably of mosques, and other features of both Byzantine and Islamic architecture. The architecture’s not the only place that we see cultural mixing. We also see that in the very people at the foreground of the painting.

Dr. Harris: [2:43] On the left side, we see contemporary Venetians, members of the confraternity, the Scuola di San Marco, the scuola devoted to Saint Mark, one of the most powerful, if not the most powerful confraternity in Venice.

Dr. Zucker: [2:56] Their presence is not unexpected, because that was the confraternity that commissioned this painting, and this painting originally resided in their building.

Dr. Harris: [3:05] Then we have lots of other figures wearing clothing that might come from Egypt, from Persia, from the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, places where the Venetians were actively trading.

[3:19] In addition to Saint Mark as the hinge of this painting, the other hinge is the artist, who’s self-portrait in red wearing this gold medal, is so prominent. That’s because the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire requested of the Venetian government, one of their great artists, and the Venetian government sent Gentile Bellini.

[3:40] Bellini spent two years there. He probably never made it to Alexandria, so this is a fantasy made up by Bellini from things he knew.

Dr. Zucker: [3:49] Let’s spend a moment with this fantastical basilica in the middle of this painting. Its buttresses almost seem to embrace all of the figures below. I think the building functions as a metaphor for the message of the painting as a whole, that is, the potential for Christian redemption.

Dr. Harris: [4:06] The figures below are both Christian and Muslim, and the site itself was one that transformed from a pagan temple to a Christian church, and then to a mosque.

Dr. Zucker: [4:20] This idea of transformation is embedded in the architecture that’s being represented here. It provides this pathway, this ideal that Egypt could once again become Christian. It’s important to remember that all of this is for a Christian audience in the city of Venice.

Dr. Harris: [4:39] Although there was this powerful religious divide, the Mediterranean world was one that was very interconnected.

Dr. Zucker: [4:47] That interconnectedness was powered by trade, by the importation and sale of luxury goods. Those luxury goods are on display in this painting. We see fine brocades, beautiful silks, brightly colored textiles. The Muslim world was seen as a place that was filled with luxury items, and technologies and knowledge that the West lusted after.

Dr. Harris: [5:10] It’s so clear when we look at the history of painting in Venice that there is this enormous interest in depicting figures from Mamluk Egypt, from the Ottoman Empire, and other places where Venetians were trading.

[5:24] It’s a reminder that artists that are so well known, like Michelangelo and Leonardo, will be asked to work for the Ottoman Sultan in Constantinople. When we think about the Renaissance as a European phenomenon and not as a Mediterranean-wide phenomenon — that even goes as far east as Persia — we’re really limiting our understanding.

Dr. Zucker: [5:46] In fact, this entire canvas seems as if it’s almost a stage that is enacting this promise of the Christianization of the Holy Lands.

[5:56] [music]

Gentile Bellini (completed by Giovanni Bellini), Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria, 1504–07, oil on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Italian Renaissance painting is often described as “realistic,” a reference to its interest in representing the world we see convincingly. This was often achieved through various tools such as the use of one-point perspective to create illusionistic space and the use of modeling to create a an illusion of three-dimensional forms. But though they may seem like a “window onto the world,” Renaissance paintings are often far more complex.

Take for example, Venetian painters Gentile and Giovanni Bellini’s twenty-five foot wide Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria, which appears, at first glance, to be a straightforward and realistic painting that relates an episode of Saint Mark (one of Christ’s apostles) preaching the Christian message in the port city of Alexandria, Egypt. However, the painting’s illusion of simplicity quickly dissolves as the viewer tries to reconcile disparate elements of time and place in the composition.

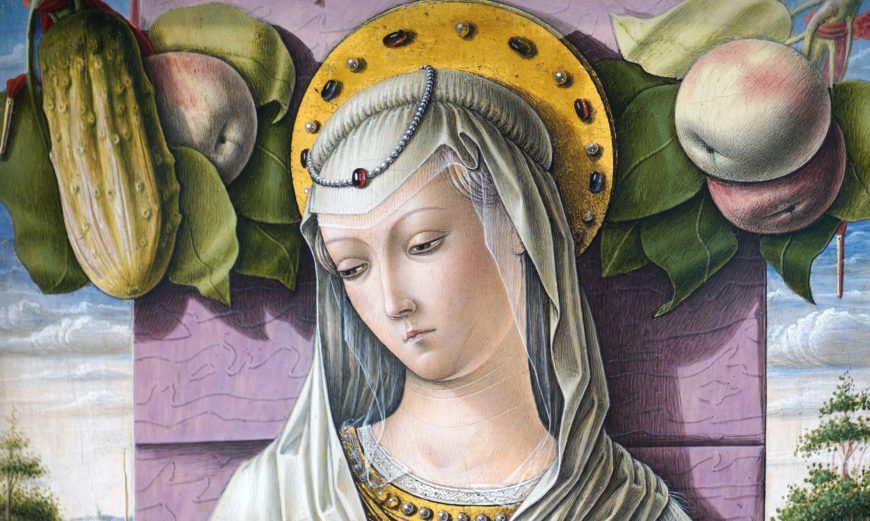

Saint Mark Preaching with 16th century Venetians behind him (detail), Gentile Bellini (completed by Giovanni Bellini), Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria, 1504–07, oil on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

For one thing, in the left foreground we see Saint Mark, shown in 1st-century (biblical era) attire of his historical era, occupying the very same public square as 16th-century Venetians (and other listeners). In addition, architectural elements in the background blend ancient Egyptian features with 16th-century Venetian ones. These dissonances (Alexandria / Venice / biblical era / 16th century) are no accident, rather they reveal a claim that Venice could transcend the limits of its historical time and its own physical borders, and lay claim to both the past and distant places. The message—that Christianity should be spread globally—neatly paralleled Venice’s burgeoning empire and colonization efforts in the Adriatic. A religious narrative was employed in service of political ideology.

Gentile Bellini (completed by Giovanni Bellini), Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria, 1504–07, oil on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

We see an expansive vista of a paved city square: on the right, we see a man leading a giraffe on a leash near a camel resting by the sand-colored buildings flanking the plaza (on the left, a dromedary can be seen just above Saint Mark). In the foreground, Saint Mark—in robes of red and blue echoing Christ’s standard color iconography—stands on a stepped dais delivering his oration.

Contemporary (16th century) figures, some in veils and turbans (detail), Gentile Bellini (completed by Giovanni Bellini), Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria, 1504–07, oil on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Behind him 16th-century Venetians wearing red and black form neat attentive rows. Other contemporary persons in a variety of attire indicating a range of ethnicities gather in the square; their veils and turbans gesture towards 16th-century Alexandria’s Muslim culture. Behind the figures, closing the square is a large building with a golden façade split into three arched sections, marked by two minarets on either side.

Reproduction of Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria in its original location, the Albergo (boardroom) of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, Venice (photo: Caffe_Paradiso, all rights reserved, used with permission)

The Scuola Grande di San Marco Confraternity

Made as one of seven paintings in a cycle depicting the life of Saint Mark, the large canvas hung in the boardroom of the Scuola Grande di San Marco, Venice’s premiere scuola dedicated to Mark. The painting cycle depicts scenes from the life of the saint, his martyrdom, and two posthumous miracles.

Pietro Lombardo, Mauro Codussi, and Bartolomeo Bon, Scuola Grande di San Marco, Venice, c. 1500 (photo, edited: Wolfgang Moroder, CC BY 2.5)

The extensive cycle in a prominent location tells us that 16th-century Venetians took this artwork seriously and that its making and message were not casual. In early modern Venice, the Scuola Grande di San Marco occupied a role important to both religious practice and statecraft. The confraternity gathered its membership from people who were neither clergy nor monastics (nuns and monks), but from the general population of Venice. Though legally separate from the government, the Scuola Grande di San Marco nevertheless participated regularly in civic rituals such as processions. The confraternity’s dedication to Saint Mark, the city’s patron saint, made this particular scuola indispensable to Venetian identity.

Basilica of San Marco, 11th century and later, Venice (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Venice & Saint Mark

The city of Venice had dedicated itself to Saint Mark ever since the 9th century when two Venetians sailed to Alexandria in Egypt and stole the saint’s holy body. Venice justified the theft by claiming the state’s possession of the relics was predestined and the saint’s own desire (because Saint Mark had chosen Venice before the city even existed historically, Venice’s existence could be declared predestined as well). They brought the saint’s body to Venice where the government built the Basilica San Marco to house the relics. The rarity and historical importance of Saint Mark’s relics turned Venice into a pilgrimage destination, conveniently located in a protected lagoon from which one could sail to the Holy Land.

Lion of Venice, Piazzetta San Marco, Venice, erected in the 12th or 13th centuries (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

State mythology promoted the connection between Saint Mark and Venice until images of Saint Mark became near-symbols of the state itself. Images of Saint Mark (whose symbol is a lion) can be found throughout Venice indicating the saint, his special protection of Venice on government buildings, infrastructure, and in non-governmental spaces such as the Scuola Grande di San Marco painting cycle. When Venice colonized locations on the Italian peninsula and on the Dalamatian coast, the state erected images of Saint Mark as a sign of Venetian rule and Venetian presence. Over time Venetian art developed pictorial strategies to exploit and enhance the connection between Saint Mark and Venice as we see in Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria.

Combining times & places

Interestingly, Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria combines multiple times and places into a unified image that appears as if it were depicting a single moment and place. Such images portraying a mobile and expansive Venice able to join histories and places outside its own historical time and borders are found through Venetian art production. [1]

Gentile and Giovanni Bellini’s painting employs one-point perspective, a mathematical grid system that produces the illusion of pictorial space, to create the impression that what the viewer sees is a single moment in time. That impression of a single moment is quickly disrupted when the viewer notices the temporal disjunction of the 16th-century figures occupying the plaza and the 1st-century Saint Mark, whose robes would have read immediately as “biblical time” to Renaissance viewers. His costume would appear particularly disjunctive.

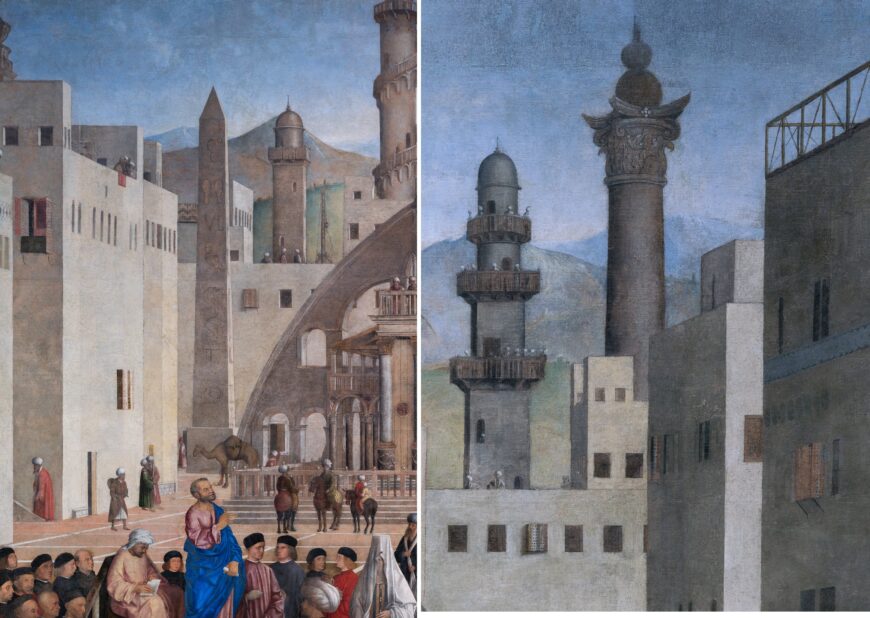

Left: obelisk; right: Pompey’s Pillar (details), Gentile Bellini (completed by Giovanni Bellini), Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria, 1504–07, oil on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The painting also complicates one point perspective’s implied sense of a single place. According to the legend of Saint Mark, we should see the saint in Alexandria, Egypt preaching in front of the Temple of Serapis. Certain details do indicate Africa, for example, the giraffe, camel, and dromedary. The obelisk, brought to the city by Emperor Augustus, and the pillar topped by an orb known as “Pompey’s Pillar” are monuments specific to the city of Alexandria. Venetian sailors and traveling merchants would have been able to see those monuments when approaching the port of Alexandria.

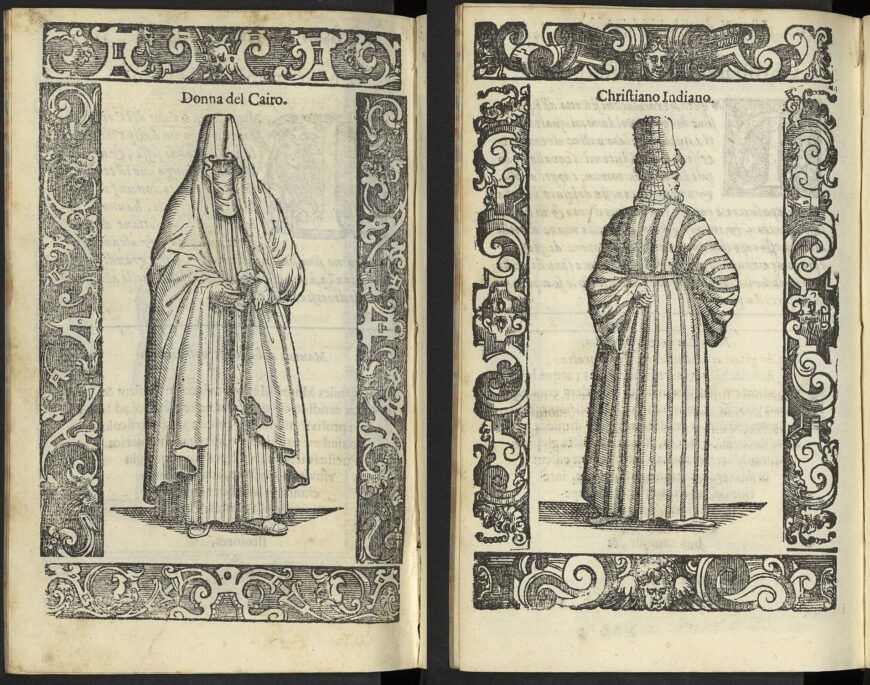

Despite the specificity of those monuments and the sand-colored buildings typical of early modern Egyptian cities, the painting refuses to settle in Alexandria entirely. The square’s inhabitants wear distinctive clothing that can be identified as Renaissance costume book types. The veiled women in white for example appear in Cesare Vecellio’s 16th-century costume book identified as “Woman of Cairo.” The men in striped attire can be found labelled “Indian Christian Man.”

“Woman of Cairo,” and “Christian Indian Man Visiting Cairo,” in Cesare Vecellio, Habiti antichi et moderni di tutto il mondo / di Cesare Vecellio, Venice, 1598 (Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, folios 424 verso and 426 verso)

The building closing the piazza remains most puzzling of all. The shape of the building calls to mind the shape of the church of Hagia Sophia in Constantinople (which the Ottomans had converted to a mosque in 1453). Venetians had great familiarity with the city due to their close trade ties with the Ottoman Empire, but also from their own sack of the city in 1204 (Venetians looted the city, stealing pieces of architecture and much of the city’s relics and art).

Anthemius of Tralles and Isidore of Miletus, Hagia Sophia, 537 C.E. (minarets added in the 15th and 16th centuries), Constantiniople (now Istanbul) (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Minarets rising on either side of the painted golden building at the end of the square suggest an Islamic mosque, but Islam as a religion dates to the 7th century, hundreds of years after Saint Mark’s death. While minarets unmistakably indicate a mosque, the oddly shaped building bears no relation to any known mosque in Egypt or the episode’s historical setting in front of the pagan Temple of Serapis. As many observers have noted, the golden mosaics, round onion domes, and arched portals recall Venice’s Basilica San Marco. Specific details seem plucked from that Venetian church: columns of porphyry (some of which may have been taken from Constantinople) and serpentine flanking portals and two scalloped parapets covered by a dome on either side of the painted basilica’s upper story mimic the stone pulpit that can be found inside Venice’s Basilica San Marco.

Architecture (detail), Gentile Bellini (completed by Giovanni Bellini), Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria, 1504–07, oil on canvas, 347 x 770 cm (Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

There is evidence that the confraternity members of the Scuola Grande di San Marco were looking to make a connection between the building in their painting and the Basilica of San Marco. In an earlier painting, Gentile had depicted the Basilica in the background of his painting Procession in Piazza San Marco. Venetian viewers familiar with that painting would have made the visual connection between the buildings. Saint Mark preaches in Alexandria in front of a building that is symbolically both a mosque (representing Venice’s 16th century rival) but simultaneously the Basilica San Marco (yet to be built) during Mark’s lifetime in the 1st century but destined to hold his holy relics. The past predestines the future and the present reaches back into the past to grab its destiny.

An argument bigger than reality

Saint Mark Preaching in Alexandria employs the tools of Italian Renaissance realism to portray an idea of Venice beyond the constraints of linear time and physical space. The subversion of the illusion of simple reality prompts thoughtful curiosity from the viewer who then is free to make associations between disjunctive elements. From those connections, prompted by the painting and composed into coherence in clear linear perspective, emerges a deeply Venetian argument about Venetian identity.