Ana Mendieta, Imágen de Yágul, from the Silueta series, 1973, chromogenic print, 50.8 x 35.3 cm (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art) © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection

A color photograph depicts a naked woman laying inside a rocky tomb. We see her body from above. Her tan arms and legs are somewhat exposed, while her upper body and head are obscured by a loose arrangement of feathery flowers, their white petals and green stems creating an aura-like haze that appears to hover over her. With her arms pinned at her side and her legs rigid, she reclines like a corpse on the uneven terrain at the bottom of the grave.

This photograph, which documents an artwork titled Imágen de Yágul (Image of Yágul) by the Cuban American artist Ana Mendieta, was taken of the artist at a Zapotec archeological site called Yágul in Oaxaca, Mexico. This image is part of Mendieta’s most renown body of work, the Silueta (Silhouette) series, which comprises over 200 pieces. In this series, which she also described as “earth-body works,” Mendieta photographed either her own body on the land, or the outline of her body within the natural environment.

Mendieta created Imágen de Yágul—her first Silueta—in 1973, during one of several summer study abroad trips to Mexico, while she was an MFA student at the University of Iowa, where she was enrolled in their relatively new experimental Intermedia Program. Describing this work as a “tableau,” Mendieta explained that she was attracted to the tomb because it was “covered with weeds and grasses,” growth that invoked temporality and “nature’s reclaiming of the site.” [1, 2]

Artist Hans Breder, director of the Intermedia Program and Mendieta’s then-romantic partner, assisted her in realizing the work. They had visited the site multiple times beforehand and had to avoid detection by security guards in order for Mendieta to quickly undress and get into the grave. She instructed Breder, who photographed her, to arrange the flowers so that they would “seem to grow from her body.” [3] Influenced by Mexican funerary rituals, the work addressed the cycles of life and nature’s ability to renew itself. [4]

Early life

Ana Mendieta was born in Havana, Cuba in 1948 to a family with close ties to the Cuban political elite. Her father was later imprisoned by the Cuban state for his involvement in the Bay of Pigs invasion. Because her family feared political retribution, Ana (age twelve) and her sister Raquel (fifteen) were sent alone to the United States as part of the Operation Peter Pan relocation program. After arriving in Miami in 1961, the sisters were transferred to Iowa, where they spent five difficult years moving through orphanages and foster homes. Later they were separated from one another, enduring a profound sense of cultural dislocation in isolation. Their mother and younger brother joined them in 1966 when Mendieta was a teenager, but their father remained in Cuba until his release and emigration to the U.S. in 1979. This prolonged familial rupture, along with the psychological toll of exile, shaped Mendieta’s sense of identity and informed her art. These themes coalesced in her earth-body works, which she later explained were a way to connect to her homeland.

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Grass on Woman), 1972, chromogenic print, 20.3 x 25.4 cm (Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.) © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection

Mendieta began her formal art training at the University of Iowa, earning a B.A. in art in 1969 and an M.A. in painting in 1972. Frustrated by the limitations of painting—she later remarked it did not have enough power or magic—she shifted toward more embodied art forms. [5] In 1972, she entered the university’s experimental MFA Program in Intermedia, which emphasized collaboration, conceptual rigor, site-specificity, and media hybridity. This environment was pivotal for Mendieta’s development, catalyzing her move into the ephemeral, body-based practices that would define her legacy. That same year, she debuted her first earth-body work, Untitled (Grass on Woman), in which she lay face-down and nude, in her friends’ backyard, instructing them to glue freshly cut grass across her body so that she would blend in with the lawn, a precursor to her first Silueta the following year. [6]

Ana Mendieta, Untitled, from the Silueta series, 1976 (1991 posthumous print), chromogenic print, 50.8 x 33.7 cm (Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton) © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection

Silueta series

Mendieta’s Siluetas began in 1973 with Imágen de Yágul and continued until 1980. Over time, the series evolved both visually and conceptually: it began with the artist’s nude body enmeshed in natural landscapes and shifted to bodily outlines, imprints, or mounds shaped as silhouettes. These works were first made in Mexico and later in Iowa. Early pieces featured Mendieta’s actual body, while later iterations employed outlines—initially created by tracing her form and later with template cutouts—or stylized figures with upraised and bent “cactus” arms, reminiscent of goddess iconography. [7] This transition from body to silhouette reflected Mendieta’s changing attitude toward the immediacy of performance: “I decided I didn’t want to be in the work anymore [because] I don’t particularly like performance art,” she explained. [8]

The Siluetas were created with ephemeral materials—mud, grass, sand, leaves, rocks, twigs, flowers, and even ignited gunpowder—and were documented through 35mm slides, color and black and white photography, and Super-8 film. Though performed without a live audience, this documentation “captured the spirit of the work,” reinforcing the ways they mediated presence, absence, and ephemerality. She referred to them as “earth-body works” to distinguish them from the monumental earthworks of male artists who, she argued, “imposed themselves on [nature].” [9] In contrast, her approach was one of “submersion and total identification with nature.” [10]

Ana Mendieta, Untitled (Labyrinth Blood Imprint), from the Silueta series, 1974, single-channel Super 8mm film (M+, Hong Kong) © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection

Her first actual silhouette was Untitled (Labyrinth Blood Imprint), created in the summer of 1974. Lying on the dirt-strewn floor of a site at Yágul, she had her outline traced (with raised arms); she bordered this shape with a ridge of dirt, and filled it in with real blood, forming a shallow crimson pool in the shape of a body. [11] Subsequent silhouettes were made on Mexican beaches and in the woods near a creek in Iowa City. In the late 1970s, she began constructing mound-shaped figures from natural materials that resembled recumbent mummies (these are sometimes attributed to her Fetish series). [12]

The Siluetas, always just under five feet tall (the artist’s height), are sometimes interpreted as self-portraits. [13] Mendieta traced their origins to her Cuban childhood, recalling crawling across sandy beaches as a baby, an early bodily encounter with the earth. [14] She also associated her imagery with Catholic symbolism, Afro-Cuban spirituality, and the iconography of ancient cultures—Mesoamerican, Taíno, Neolithic, Minoan, Maltese, and Egyptian. Yet, as she clarified, her work was not “a ritual,” but rather “a way of asserting [her] emotional ties with the earth as well as conceptualizing culture.” [15] She also described it as “a return to the maternal source … the original shelter within the womb.” [16] Initially embraced by second-wave feminists as evocations of the “Great Goddess,” the Siluetas were later critiqued as essentialist by feminists aligned with social constructionism in the 1980s. [17] More recent scholarship considers the series through frameworks of exile, hybridity, performativity, and poststructuralism. Mendieta herself connected the works to the trauma of displacement and exile, describing them as gestures of longing for her lost homeland.

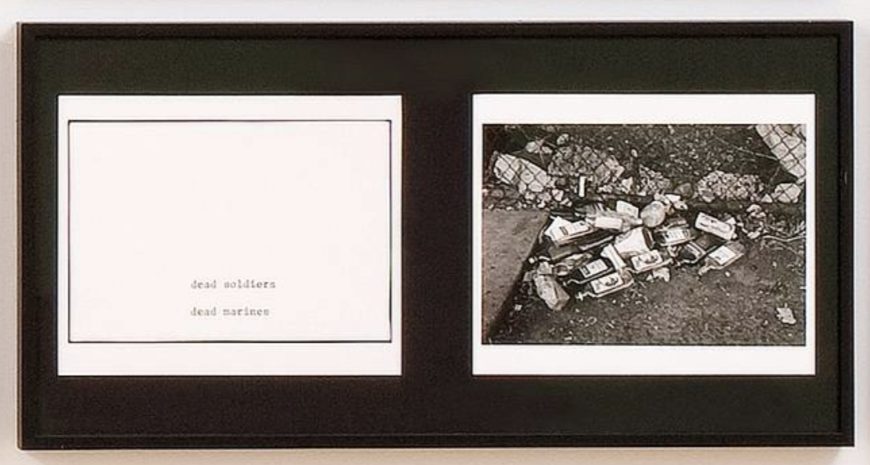

Press release for Ana Mendieta’s exhibition at A.I.R. Gallery “Silueta Series 1979,” 1979 (A.I.R. Gallery, New York)

Feminism

Mendieta’s early association with feminist discourse was shaped in part by critic and curator Lucy Lippard, who met her as a student in Iowa, and who framed her work within a feminist context via artists in Ms. Magazine (1975) and Art in America (1976). After moving to New York City in 1978, Mendieta joined A.I.R. Gallery—the first artist-run cooperative for women in New York—and had a solo exhibition of her Siluetas there in November 1979.

She also participated in the gallery’s taskforce on discrimination against women and minority artists, reflecting her commitment to addressing racial and gender inequities within the art world. In September 1980, she co-curated Dialectics of Isolation: An Exhibition of Third World Women Artists in the United States at A.I.R. with artists Kazuko Miyamoto and Zarina. This exhibition challenged the exclusions prevalent in predominantly white feminist art spaces by foregrounding the voices and works of women artists of color, embodying what is now recognized as an intersectional approach to feminist curatorial practice. Mendieta resigned from A.I.R. in 1982, the same year she contributed “La Venus Negra” to the feminist journal Heresies, where she invoked a postcolonial feminist perspective through the retelling of a Cuban legend. [18]

While Mendieta’s work was often embraced by second-wave feminists, her own relationship to feminism was complex and increasingly critical. She became disillusioned with the essentialist readings imposed on her work—particularly those rooted in goddess imagery—and began to resist these associations. Some scholars have argued that her interest in ancient spiritual and ritual traditions from Cuba, Mexico, and other ancient world cultures was often misunderstood by white feminist critics. [19]

Ana Mendieta, Anima (Alma/Soul), from the Silueta series, 1976 (1977 print), chromogenic print, 34.3 x 50.8 cm (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.) © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection

Death and legacy

Mendieta’s life was tragically cut short in the early hours of September 8, 1985, when she fell from the 34th-floor window of the Greenwich Village apartment she shared with her husband, Minimalist sculptor Carl Andre. The couple met in New York in 1979 and married in Rome in January 1985 during her fellowship at the American Academy. Eight months later, Andre called 911, claiming Mendieta had died by suicide. However, inconsistencies in his statements, scratches on his face, and a doorman’s report of hearing a woman scream “No, no, no, no!” moments before the fall led to his arrest for second-degree murder.

The legal case was protracted and fraught. Two grand jury indictments were dismissed before a third allowed the case to proceed to trial. Andre chose a bench trial, avoiding a jury. The prosecution emphasized Mendieta’s successful career and lack of suicidal tendencies. In contrast, the defense relied on racialized and gendered stereotypes, portraying her as an emotionally unstable Latina. Her Silueta series was misrepresented as evidence of a death wish, while testimony about Andre’s prior aggression and Mendieta’s desire to leave him was excluded. Andre declined to testify and was acquitted in 1988, a verdict that some believe exposed both the justice system’s failings and the art world’s discomfort with publicly addressing the case.

Mendieta’s death remains a fraught and contested episode in American art history, examined extensively across both scholarly and popular media, including print and audio formats. [20] While some have read her Silueta series as tragically foreshadowing her demise, others caution against overinterpreting her work in this way. [21] Critics argue that focusing narrowly on the circumstances of her death risks, in the words of Cuban American artist Coco Fusco, “fetishizing [her] as a victim instead of celebrating her tenacity and resilience as an artist.” [22] Rather than framing her legacy in terms of domestic abuse or loss, many advocate centering her significant contributions instead.

Ana Mendieta, Untitled, from the Silueta series, 1976 (1991 posthumous print), chromogenic print, 32.7 x 49.21 cm (The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles) © The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection

Mendieta’s Siluetas remain among the most innovative and influential examples of late 20th-century body art. Bridging feminist performance, postcolonial critique, ecological poetics, and intermedia strategies of photographic and filmic documentation, her works are distinct for their formal and conceptual hybridity, and for how they reimagined self-representation through the lens of diaspora and embodiment, anticipating the kinds of intersectional and decolonial aesthetics that would become increasingly popularized in contemporary art after her death.