Hans Bellmer, The Doll, 1935–37, gelatin silver print, 24.1 x 23.7 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, New York)

The first time I encountered Hans Bellmer’s life-sized double-doll sculpture—at an exhibition I helped organize at the International Center of Photography in 2001—my feelings were a mix of shock, revulsion, and fascination. In The Doll photo-series based on the sculpture, Hans Bellmer assembled and reassembled doll parts that he had constructed with his brother Fritz—also a trained engineer. Bellmer accentuated and duplicated their female sex organs, splaying them out on the floor as a still life before the viewer. Due to the nature of the work from this series, he is often pegged by scholars as a misogynist-leaning, female-objectifying artist—even to the extent of having alleged “pedophiliac” visual fantasies. [1] But Bellmer also provides a compelling example of the complexities of reading artwork retroactively. As scholars since the year 2000 have suggested with The Doll and other photographs from the series, Bellmer also expressed his own gender-identity issues, engaged the alternative realities of Surrealism, and commented on Nazi Germany’s notions of the “perfect” versus the degenerate body.

Bellmer was born in German-speaking Silesia but had been exposed to French Surrealism on trips to mid-1920s Paris, where he met the Italian artist much beloved by the Surrealists, Giorgio De Chirico, who often used mannequins as subjects for his paintings. Surrealist preoccupations with the uncanny melded with numerous highly personal events once the Bellmer family moved to Berlin in 1931. Together, these inspired the artist to construct his first life-sized doll in 1933—the same year Hitler took over as German Chancellor—which he could use as a subject for experimental photography. [2] That was followed by a more complex second doll in 1935 which was composed of a central ball joint that allowed for more flexibility and various appendages to be attached. While that opened up the object for Bellmer and kindled his desire to create various associations of gender and identity, it concurrently led to accusations of purposeful violence done to the doll’s “body” through implied amputations and sexualization.

As Therese Lichtenstein explored in depth in her 2001 monograph Behind Closed Doors: The Art of Hans Bellmer, the convergence of three events between 1930–32 inspired him to construct the first doll. They included his mother sending him a box of his childhood toys—including broken dolls. He also had a Lolita-like fixation on his teenage cousin Ursula Naguschewski, newly arrived in Berlin where the Bellmer family had moved. And finally, he attended a local production of The Tales of Hoffman, a Jules Offenbach opera, where the first act centered on a “beautiful, lifelike doll Olympia.” [3]

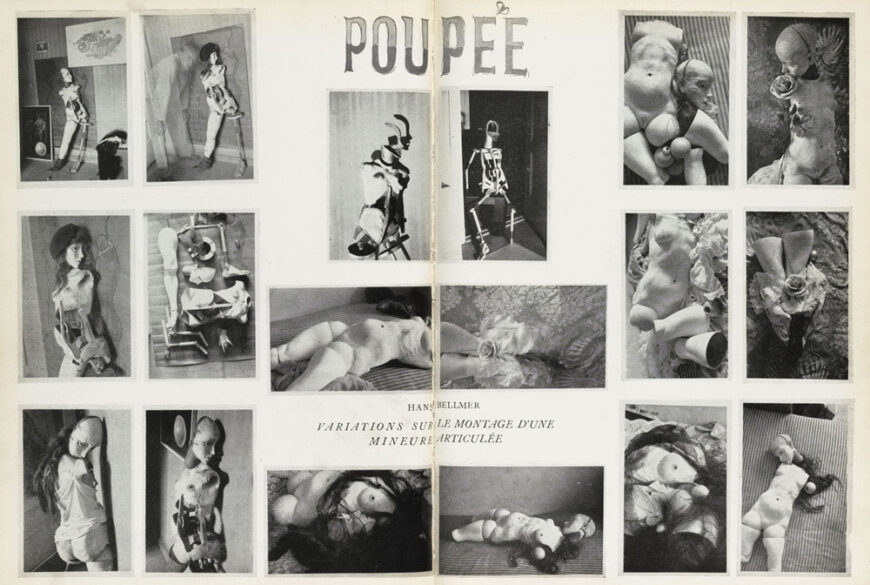

Hans Bellmer, “Poupée: Variations sur le montage d’une mineure articulée (Doll: Variations on the Montage of an Articulated Minor),” Minotaure, number 6 (December 1934)

The circulation of Bellmer’s Dolls

The artist took approximately 30 black-and-white photographs of the first doll, some of which were included in the 1934 book Die Puppe (“Dolls”) and which also appeared in the Surrealist publication Minotaure in December of 1934. His cousin Ursula, then a Sorbonne student in Paris, had shown them to the Surrealist founder and poet André Breton at Bellmer’s request, and they caused “such a stir” that they were quickly published as the double-page spread above.

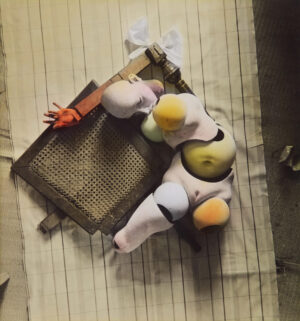

Hans Bellmer, La Poupée, 1935, hand colored gelatin silver print, 29.2 x 27.3 cm (private collection)

Parts of that doll were then incorporated into the more monumental second doll in 1935, which was the subject of more than 100 photographs, including the images that have become “textbook” Bellmer such as The Doll (La Poupée, 1935). This image was hand-tinted in candy-colored pastels, lovingly applied by Bellmer—an unusual practice when black-and-white photography was accepted as the default—with the parts adhered to a chair-caning surface. [4]

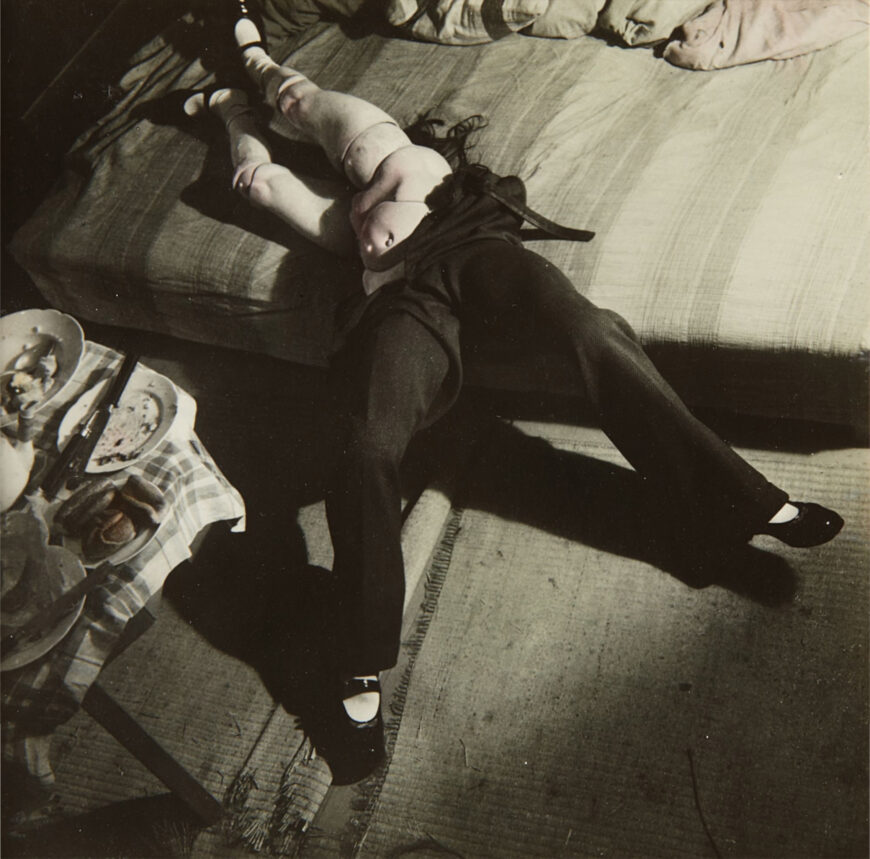

In a way, it’s unfortunate that this image from the series has become one of the most widely disseminated examples of Bellmer’s work. As striking as it is, other images of the second doll speak more directly to the complexity of gender and political issues that the artist sorted out through these performative sculptural acts before photographing them, with the photographs then becoming his definitive works of art. A different photograph also entitled The Doll (the repeated titles can become confounding) from 1936 shows how the ball joint of the more flexible second doll can be used to attach multiple legs.

Hans Bellmer, The Doll, 1936, hand-colored gelatin silver print, printed 1949, 13.7 x 13.7 cm (private collection)

Bellmer therefore had more choices of garb here and chose to put one set of legs into men’s trousers and another set laid bare to show off girly patent-leather shoes. The artist was very forthcoming about his own lingering gender confusion, speculating that it may have been precipitated by his tyrannical, fascistic father who was obsessed with masculinity, underwhelmed by his sons’ lack of demonstration of it, and who eventually joined the Nazi Party. Bellmer described himself and his brother as children: “In fact, we were probably rather adorable, more like little girls than the formidable boys we would have preferred to be. Yet, it seemed to be more fitting than anything else to lure the brute out of his place in order to confuse him.” [5] And so it seems safe to presume that he often identified himself directly with the doll.

Rejecting Nazi “perfection”

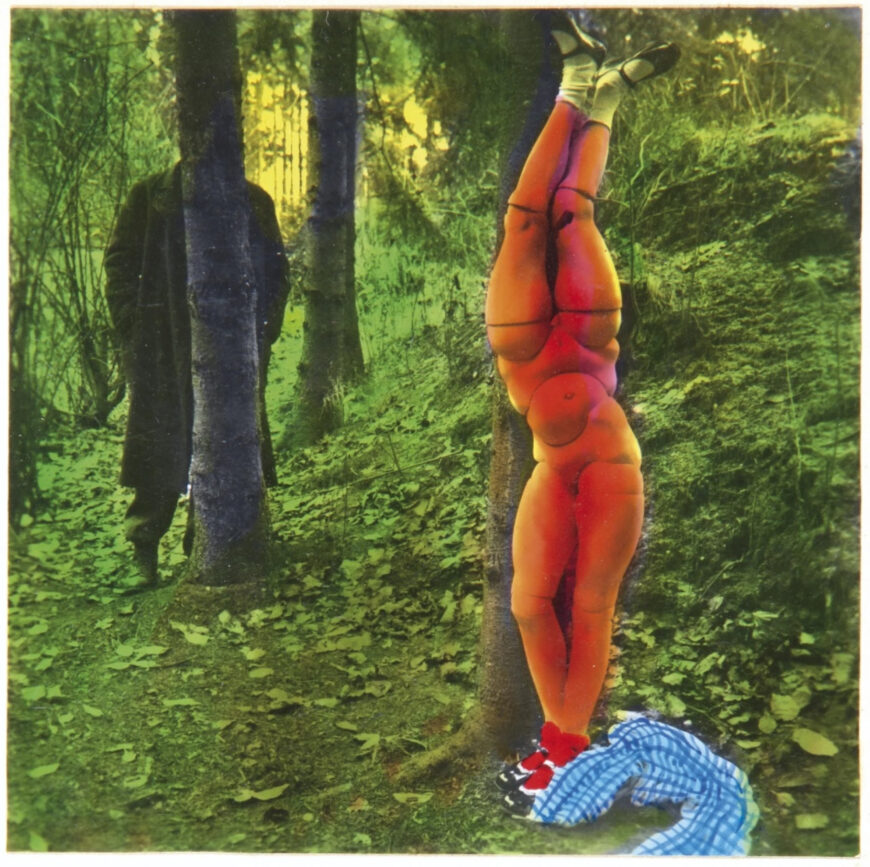

One of the most astonishing experiments with the doll parts is witnessed through a 1936 Doll photograph, a hand-colored photographic print depicting a torso where a second set of legs replace the arms and head and which is dressed in red and clad in two sets of the black leather shoes: the type typically worn by young girls. Concurrently in the forest setting, an ominous and voyeuristic figure dressed in all black hovers behind a nearby tree, ready to pounce, with all the implied features of a strongly-built male.

Hans Bellmer, The Doll (La Poupée), 1936, hand-colored vintage gelatin silver print, 6 x 5.5 cm (private collection)

Is this scene based on voyeuristic sexual fantasies? Or perhaps it refers to the suffocating environment of surveillance instituted by the Third Reich, a regime Bellmer protested, and as a result, refused to work or exhibit with publicly. He claimed The Doll was a political artwork, but many viewers focused on the sexual content. Other hand-tinted images of the doll created a sense of diseased skin, which the art historian Therese Lichtenstein emphasizes was a protest against the desire for perfection in Nazi “body culture.” The persuasive combination of possibilities is precisely what complicates Bellmer’s arresting and disturbing works.

Bellmer and Surrealism

The interwar Nazi politics of Germany became so constricting for Bellmer that when his sickly wife died in 1938, he moved to Paris where he lived for the rest of his life. He was immediately embraced by the Surrealists there who included him in the International Exhibition of Surrealism in 1938, with its famed “Street of Mannequins.” Surrealist poet Paul Eluard wrote poems to accompany Bellmer’s second doll’s photographs in the book Games of the Doll, although it was not published until 1949. In the late 1940s Bellmer also collaborated with the author Georges Bataille, providing illustrations for his 1947 reprint of the novella Story of the Eye.

Later in his career, he began additional “body-art” collaborations with his lover, the German writer and artist Unica Zürn. However, Zürn suffered deeply from her mental health issues, and died in 1970. The following year he was able to enjoy a definitive retrospective at the Centre national d’art contemporain, Paris, including an overview of his dolls. He died a few years later and was laid to rest in the illustrious Père Lachaise Cemetery in his beloved adopted city, where the artistic movement of Surrealism had always welcomed him with open arms.

Notes:

[1] Ken Johnson, “Desiring Machines: Hans Bellmer and Surrealist Strategies in Contemporary Photography,” New York Times (May 3, 2002). This review shows that those assumptions about Bellmer lingered even after the turn of the millennium.

[2] Freud’s essay regularly invoked dolls, mannequins, mirrors, and other doubles as examples of the “uncanny.” Sigmund Freud, “The Uncanny,” (1919), The Standard Edition of the Complete Works of Sigmund Freud, volume 17, translated by James Strachey (London: The Hogarth Press, 1964), pp. 217–56.

[3] Therese Lichtenstein, Behind Closed Doors: The Art of Hans Bellmer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), p. 21.

[4] For an example of such a textbook, see Mary Warner Marien, Photography: A Cultural History, 5th edition (London: Laurence King Publishing, 2021), p. 253.

[5] Hans Bellmer, “Die Vater (The Father),” 1936, translated by Allen S. Weiss from the French, “Le Père,” which appeared as a prose poem in Le Surréalism, number 4 (Spring, 1958). See Lichtenstein, p. 177.

Additional resources

Read about Surrealism and Women

Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss, Formless: A User’s Guide (Princeton: Zone Books, 2000).

Therese Lichtenstein, Behind Closed Doors: The Art of Hans Bellmer (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001).

Sue Taylor, Hans Bellmer: The Anatomy of Anxiety (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002).