Robin Forbes, View down West Broadway, SoHo, N.Y.C., c. 1975-76 (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

Experimental, experiential, and ephemeral

In November 1970, poet Peter Schjedahl entered a strange space. “Dingly lighted,” it housed art that was “scarcely distinguishable” from its “crumbling walls,” “rugged floors,” and “ruined fixtures.”[1] The site was 112 Greene Street: one of New York City’s first alternative art spaces. Rundown and rough-hewn, it catalyzed a movement that transformed the nature of art and of its display.

An alternative art space is a venue for presenting (and, in some cases, creating and distributing) art that is distinct from the traditional commercial art gallery and the art museum. The descriptor “alternative” indicates its defiance of these older models: the first, driven by profit; the second, critiqued as rarified and exclusionary. By featuring work that expanded the definition of what art could be—often, to a point beyond recognition—alternative spaces posed a profound challenge to the art world’s status quo.

Few alternative art spaces existed before 1970. Yet, from 1971 through the decade’s close, hundreds arose in cities across the United States. New York City—specifically, the SoHo neighborhood in lower Manhattan—was their epicenter. Frequently initiated and run by artists, they cultivated art that was often neither recognized by nor admitted to established institutions. Informed by contemporaneous struggles for civil rights and liberation, they opposed the idea that art was a commodity for sale and that it should endure like work made with conventional materials such as canvas, marble, and bronze. Experimental and collaborative in spirit, alternative art spaces were sites of profound innovation. Together, they shaped the artistic ethos of the 1970s.

Example of the white cube esthetic, Josef Albers exhibition at L’Espace de l’Art Concret, Mouans-Sartoux, France (photo: Jean-Pierre Dalbéra, April 14, 2019, CC BY 2.0)

Not a white cube

During the 1970s, both museums and commercial galleries in New York City ascribed to the convention of the “white cube”: a space structured by right angles and smooth white walls. Introduced in the early-20th century, the white cube was coincident with the advent of modern art, and replaced the crowded, upholstered exhibition spaces of the 19th century with austere, streamlined interiors. Its architecture was heralded as neutral and self-effacing: an unobtrusive container for the art on view. The white cube, however, was far from disinterested. Its pristine, polished look promoted art that upheld ideas of purity and that art was set apart from the everyday experience of the outside world. Premised on the denial of social issues and historical realities, the result was a timeless “non space,” in the words of art historian Thomas McEvilley.[2]

Certification of artists applying for occupancy in Soho, 1970-71 (Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution)

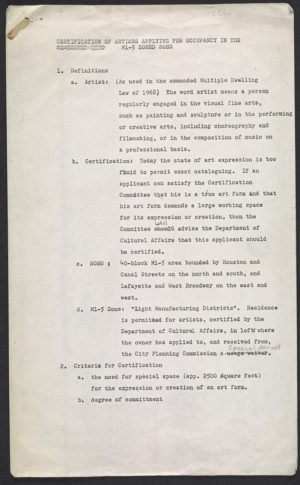

Since the 1960s, New York City’s commercial galleries had clustered uptown, lining 57th Street and the stretch of Madison Avenue from 57th up to about 86th Street. Alternative art spaces, by contrast, took root in SoHo. Once a bustling light manufacturing district, SoHo fell into vacancy and disrepair as the city shifted toward a postindustrial economy. Its 19th-century buildings, with their cast-iron façades, high ceilings, and unpartitioned floors, were ill-suited to the demands of modern manufacturing. In the early 1960s, artists began to settle in these disused buildings, enduring harsh conditions in exchange for cheap rent, ample space, and abundant light. Their presence was salutary: by repairing, retrofitting, and inhabiting otherwise empty structures, they improved the neighborhood’s conditions, paving the way for its revitalization in the years to come.

As artists moved to SoHo, alternative art spaces followed, benefitting from the same practice of adaptive reuse. The raw interiors of former factories and warehouses became a hallmark of the first wave of these venues. Lacking the capital for major renovations, artists made improvements on a DIY basis. More than a symptom of economic constraint, the crudeness of these settings was embraced as a deliberate aesthetic. Their idiosyncrasy countered the homogeneity of the white cube—replicable anywhere and, thus, specific to nowhere. Dilapidation became an asset: a prompt for producing art. These vacant factories once again became a means of production: a place in which art could be made.

Pushing against the white cube’s ideal of static, pristine objecthood, SoHo’s artists made use of unconventional materials whose unprocessed, “crummy” nature echoed that of their environment.[3] Many foregrounded the act of making, claiming the process of facture as inseparable from the form and meaning of their work. Their art crossed disciplinary bounds, often fusing media—painting, sculpture, dance, theater, architecture, and so forth—that modern art orthodoxy had deemed distinct. “Doomed to destruction,” as Schjeldahl put it, such art typically lasted for a limited time period—the run of an exhibition, for instance—before ceasing to exist.[4] Recognizing ephemerality as a primary condition, much of this art survives only through photographs and verbal accounts.

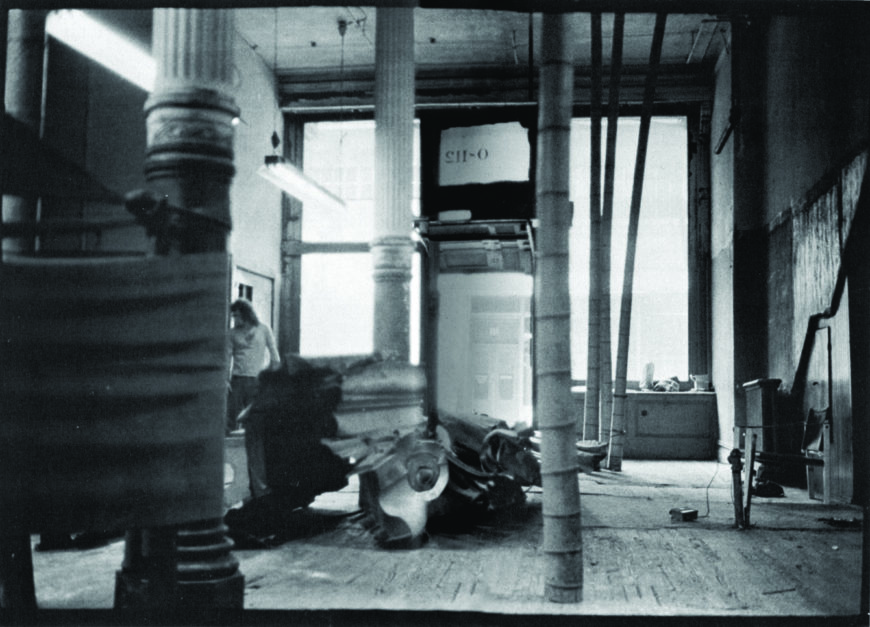

Alan Saret installs an exhibition at 112 Greene Street, c. 1970. (photo: Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone, © Cosmos Andrew Sarchiapone)

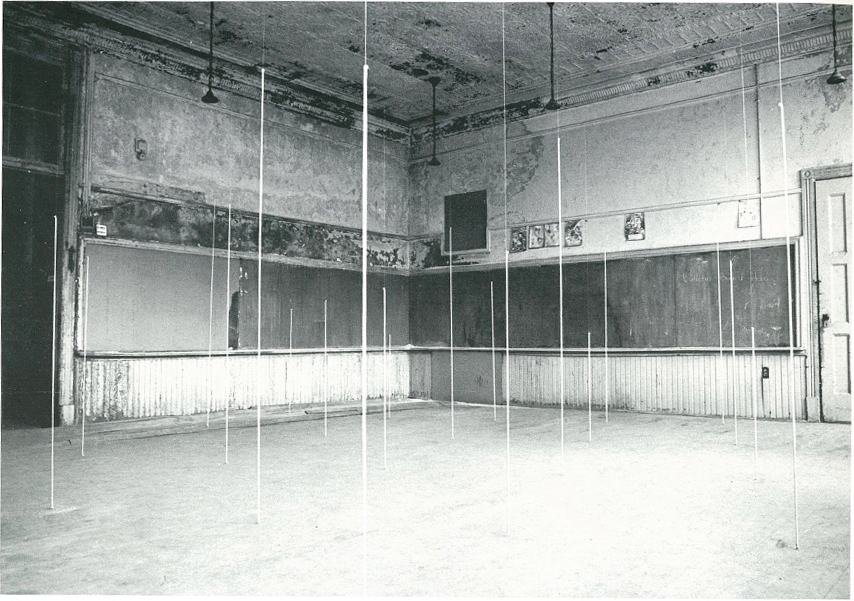

112 Greene Street

112 Greene Street was founded by artists Jeffrey Lew, Alan Saret, and Gordon Matta-Clark in 1970. It occupied the ground floor and basement of a former rag-picking factory: a recycling venture that was itself recycled by artists. Secured with the financial support of Saret’s uncle, it was a space where artists could make and display work. Absent a formal governing committee, artists curated their own shows in a casual, improvisatory manner. “A piece would go up and a piece would come down and another piece would come in and some other pieces would stay and then finally those pieces would go and more pieces would come in,” Saret breathlessly explained.[5] The result was a collaborative, cross-disciplinary ethos where artists of diverse backgrounds created in close proximity. Sculptors and architects participated in performances; performers likewise engaged with sculpture and architecture, integrating them as props and sets. Reciprocity, revision, and flux became the conditions of artwork and built environment alike.

To the average passerby, 112 Greene Street must have seemed in dire need of repair. Lew decided to leave it as it: “112 Greene is really funky and should be left funky,” he affirmed.[6] The inaugural exhibition, which opened in October 1970, was a collection of different ways to intervene in built space, with artists variously cleaving walls, removing pieces of steel from the floor, burrowing beneath the basement, wrapping columns with rubber, and extruding plastic foam from windows. The venue’s name, derived from its street address in SoHo, signals the closeness with which content and context were held. “You couldn’t isolate anything from the world in 112, because 112 took over,” artist Richard Nonas recalled.[7]

Artists Space

Located at 155 Wooster Street, just a few blocks south of 112 Greene Street, Artists Space opened in October 1973. Founded by art historian Irving Sandler and arts administrator Trudie Grace, it was backed by the New York State Council on the Arts (NYSCA). Established by Governor Nelson Rockefeller in 1960, NYSCA was a key source of funds for alternative art spaces in the city. Alongside the National Endowment for the Arts, created by President Nixon in 1965, NYSCA supported arts venues, including those without the financial means to survive otherwise. The resources of both organizations grew over the decade: NYSCA’s budget increased tenfold in 1971 alone, while the NEA’s budget swelled from $9 to $99.9 million between 1970 and 1977.[8]

Artists Space was a product of this upsurge in public funding for the arts, much of which was received by organizations in New York City. External money, however, did not come without strings. Grant-making agencies imposed guidelines for administration, budgeting, and programming that tempered the spontaneous, boundary-blurring spirit of alternative artistic practices. Keenly aware of this dilemma, Artists Space insisted on artists’ prerogative to control their own context. All exhibitions were artist-curated, with established artists selecting lesser-known peers, with whom they showed together in the space. The first year, Sandler devised a list of 21 leading artists—among them, Vito Acconci, Romare Bearden, Nancy Graves, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Dorothea Rockburne, Richard Serra, and Jackie Winsor—each of whom nominated one unaffiliated artist.[9] New selectors were appointed for the ensuing seasons, while an artist could be chosen only once, thus ensuring a plurality of voices and approaches. Emphasizing hybridity, process, and unconventional materials, Artist Space explored urgent formal and political issues, from the nature of postmodernism (as in Douglas Crimp’s 1977 exhibition, “Pictures”) to questions of identity (as in Adrian Piper’s 1981 installation and performance, It’s Just Art).

A.I.R.

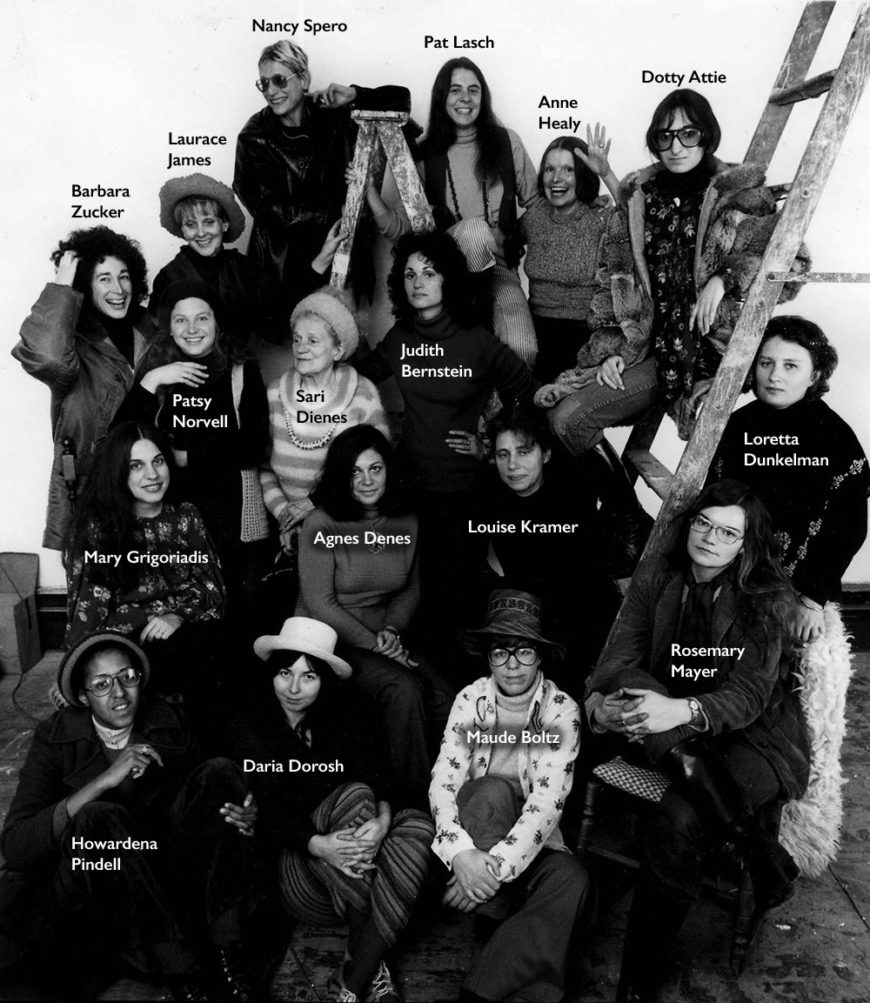

Exemplifying the alliance of alternative art with progressive politics, A.I.R. was the first alternative art space in the United States devoted exclusively to women artists. Fueled by the burgeoning feminist movement and concurrent struggles for social justice, it strove to redress the systemic discrimination against women in the art world. Solo exhibitions by women at American museums were virtually nonexistent in the 1970s, while many uptown galleries devoted less than 10% of their programming to women artists. Short for Artists in Residence, Inc., the venue was titled after the law of the same name. Passed in 1971, the A.I.R. law granted artists in New York City the right to live in abandoned industrial buildings, which zoning rules had previously barred from residential use. The proposal was initially for a homophone, “EYRE Gallery,” after Charlotte Brontë’s eponymous feminist heroine, Jane Eyre. The feminist statement transformed into a salute to SoHo—and an affirmation of women artists’ right to establish themselves there.[10]

Inspired by feminism’s collective approach, A.I.R. assumed a cooperative structure. Artists Susan Williams and Barbara Zucker were joined by Dotty Attie, Maude Boltz, Mary Grigoriadis, and Nancy Spero, who selected fourteen additional women artists to create a stable of twenty, including Judith Bernstein, Agnes Denes, and Howardena Pindell. Absent a director, all decisions were made by majority vote. Collectively, the group obtained and renovated 97 Wooster Street, a former machine shop. The inaugural exhibition opened in September 1972 and featured ten of the twenty founding artists. Defying the notion that art made by women must somehow look “feminine,” the work exhibited was marked by a multiplicity of media and approaches—“representational, abstract, expressionist, conceptual, minimal, lyrical (or minimal-lyrical),” in the description of art critic Lucy Lippard.[11]

P.S.1

Part arts organization, part real-estate entity, the Institute for Art and Urban Resources (I.A.U.R.) reclaimed empty buildings throughout New York City as paired exhibition and studio spaces. Founded by Alanna Heiss, an ambitious arts administrator and organizer, in 1971, the I.A.U.R. operated through a blend of ingenuity and advocacy, collaborating with the city’s government and landlords to identify and rehabilitate derelict spaces. In April 1976, the I.A.U.R. signed a twenty-year lease with the city for Public School 1 (P.S.1): a vacant school building in Long Island City, Queens, that was slated to be sold and demolished. Renamed Project Space 1, the repurposed building debuted in June 1976 with the group exhibition “Rooms.”

Seventy-eight artists were assigned “rooms,” including classrooms, hallways, bathrooms, closets, the basement, the attic, and the roof, in which to work. As at 112 Greene Street, P.S.1’s dilapidated condition served as a prompt, with artists engaging its peeling walls, uneven floors, and strange sightlines as raw material for their projects. Defined by a “disaster area ambiance,” the building compelled the creation of art that “could survive its surroundings, rather than relying on them to ‘authenticate’ it,” as art critic Nancy Foote remarked.”[12]

MoMA PS1, 2008 (photo: jarito, CC BY 2.0)

A legacy of experimentation

All of the aforementioned spaces exist today, albeit in altered forms. Now named White Columns, 112 Greene Street relocated to 325 Spring Street in 1979. Artists Space made multiple moves, occupying five different buildings in lower Manhattan before securing 11 Cortlandt Alley in 2019. In 2005, A.I.R. took root in Brooklyn. In 1999, P.S.1 merged with The Museum of Modern Art, New York, to become MoMA PS1, preserving its location in perpetuity. Many other early venues were not so fortunate, folding under financial pressure caused in part by the rapid gentrification of SoHo that artists’ pioneering efforts had enabled. Their legacy, however, reverberates, informing the shifting landscape of contemporary art, which is often sited in lapsed industrial buildings prized for their idiosyncratic, unrefined, and cavernous interiors. Insisting that content and context exist in generative reciprocity, alternative art spaces fueled a moment of extraordinary creativity and promise: one that charted new paths and possibilities for art in the wake of modernism.

[1] Schjeldahl, “Sculpture ‘Found’ in a Rag Factory,” The New York Times, November 1, 1970, 125.

[2] McEvilley, “Introduction,” in Brian O’Doherty, Inside the White Cube: The Ideology of the Gallery Space (San Francisco: The Lapis Press, 1986), 8.

[3] Nancy Foote, “Apotheosis of the Crummy Space,” Artforum 15, no. 2 (October 1976): 28–37.

[4] Schjeldahl, 125.

[5] Saret quoted in 112 Workshop, 112 Greene Street: History, Artists & Artworks, ed. Robyn Bretano (New York : New York University Press, 1981), reprinted in Alternatives in Retrospect, 34.

[6] Lew quoted in “112 Greene Street,” Avalanche 2 (Winter 1971): 12.

[7] Nonas quoted in Jessamyn Fiore, 112 Greene Street: The Early Years (1970–74) (Santa Fe: Radius Books; New York: David Zwirner, 2012), 25.

[8] “National Endowment for the Arts: A History, 1965–2008,” https://www.arts.gov/sites/default/files/nea-history-1965-2008.pdf

[9] 5000 Artists Return to Artists Space: 25 Years, ed. Claudia Gould and Valerie Smith (New York: Artists Space, 1998), 22.

[10] “Artists Space: History,” https://artistsspace.org/about#history

[11] Lippard, “A.I.R.,” https://www.airgallery.org/essays-2/2016/6/2/air

[12] Foote, 30.

Additional resources

A.I.R.

Artists Space

MoMA PS1

Printed Matter

White Columns

Apple, Jacki. Alternatives in Retrospect: An Historical Overview 1969–75. New York: The New Museum, 1981.

Ault, Julie, ed. Alternative Art New York 1965–1985. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; New York: The Drawing Center, 2002.

Shkuda, Aaron. The Lofts of SoHo: Gentrification, Art, and Industry in New York, 1950–1980. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2016.