Martha Rosler, The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, 1974–75, forty-five gelatin silver prints of text and image mounted on twenty-four backing boards (SFMOMA) © Martha Rosler

“A poetics of drunkenness” is how the artist Martha Rosler once described her 24-panel photo-text installation, The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems. [1] The work pairs black-and-white photographs of abandoned storefronts and building façades with metaphors for drunkenness composed on typewritten pages, and was created during a severe economic crisis in New York City at the end of the Vietnam War.

Rosler’s images of buildings on the Bowery, a string of mostly abandoned structures on Manhattan’s lower east side, came about, as the artist described in a 2014 interview, as the result of strolls the artist took in the evening from her apartment in the East Village through the Bowery on the way to Battery Park. Conceived partly as a meditation on the current economic downturn in New York, The Bowery was at the same time a response to the documentary tradition in American photography.

Questioning the documentary approach

Rosler’s decision not to include any actual people in her photographs—but to show traces of human presence, such as empty liquor bottles and other litter—was a counter-documentary practice, a refusal of the conventions of long-standing practices of documentary photography. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, social reform photographers including Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine made portraits of American immigrants and laborers to advocate for improvement in housing, work conditions, and other social reforms. In the 1930s, several photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Gordon Parks furnished images of sharecroppers and others impacted by the Great Depression in the 1930s and 1940s to encourage support for Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. These pre-World War II, socially engaged photographic practices were dependent upon the privileged making images of the less privileged.

This particular documentary approach was soon questioned by Robert Frank’s book of photographs The Americans (1955), as well as by Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander, and Diane Arbus (featured together in the 1967 show “New Documents” at the influential Museum of Modern Art in New York). As curator of “New Documents,” John Szarkowski, suggested, “[t]heir aim has been not to reform life but to know it.” [2] That “knowing” occurred not in mass magazines or government reports, but in art museums and galleries. It was a newly cynical, unsentimental, post-World War II approach to documentary photography.

The human-free cityscapes of Rosler’s The Bowery could be seen as part of this trajectory, however it is important to underscore that Rosler took aim at the documentary tradition in total, as well as the museum’s effort to turn documentary photography into art. This was part of a larger assault upon modern art by a younger generation of artists who rejected the idea that artworks should be beautiful objects languishing in museums and disconnected from life. The movement of conceptual art that arose in the late 1960s took aim at the museum and sought to create a bridge between art, everyday life, and social politics. Rosler wedded the concerns of conceptual art to those of documentary photography.

“Poetics of Drunkenness”: How Text and Images Connect

By the 1970s, it became clear that utopian visions of a “universal” language of art and architecture, an important feature of modernism were no match for a century of wars, genocides, and other global catastrophes. Postmodernism brought a new wave of questioning the modernism and its certainty in the power of art to improve all it touched.

Detail. Martha Rosler, The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, 1974–75, forty-five gelatin silver prints of text and image mounted on twenty-four backing boards (SFMOMA) © Martha Rosler

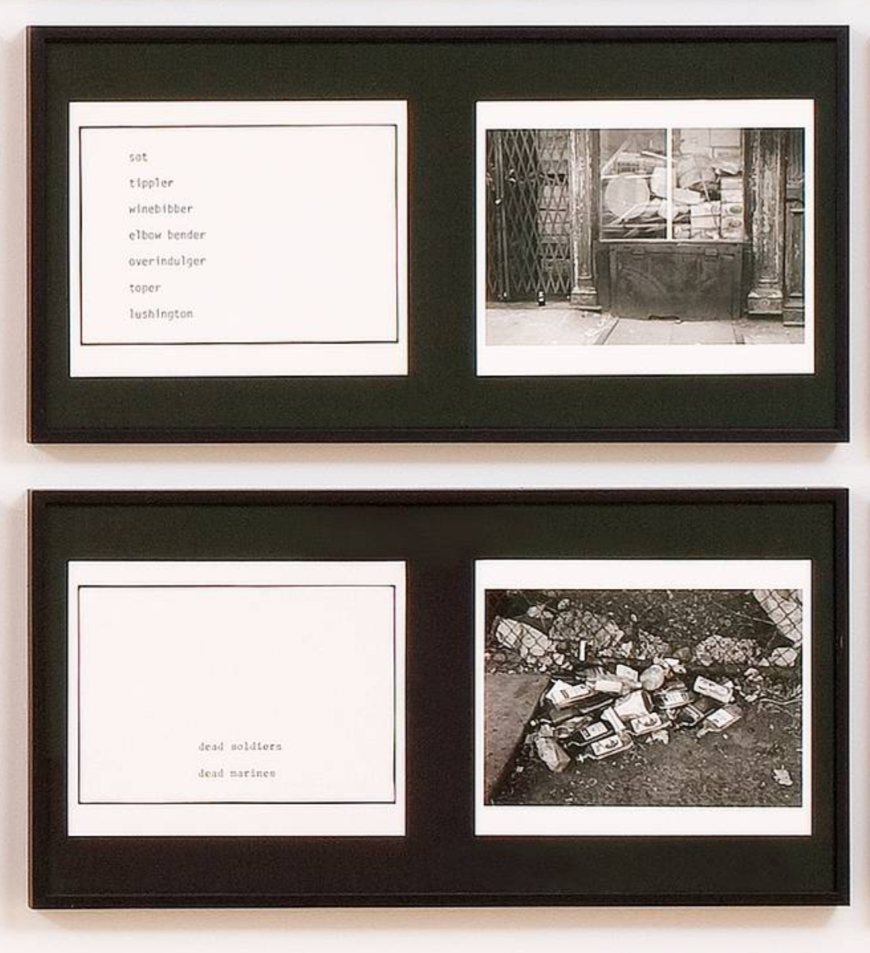

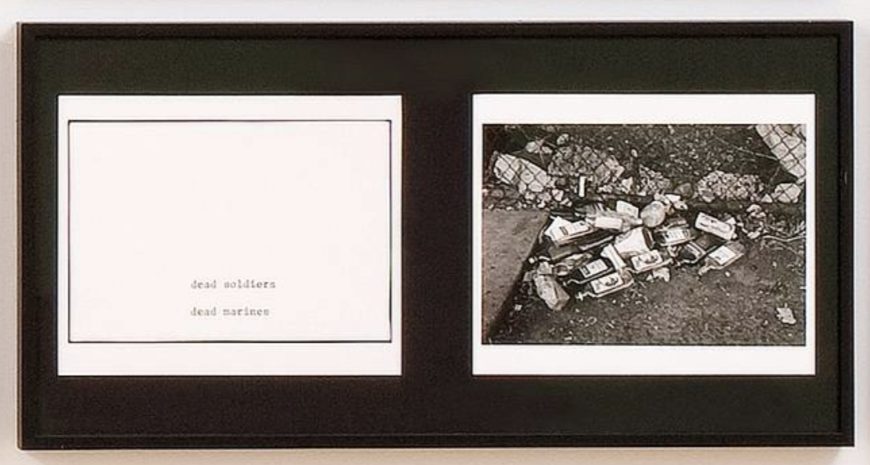

Language (visual and textual), Rosler suggests, fails when it comes to the task of “knowing” the toll of the economic downturn and wars on the people of the Bowery. For example, in one panel (see above, top set), Rosler pairs a photograph of an abandoned storefront filled with objects that appear to be lampshades (the Bowery was then also home to wholesalers) with a vertical, left-justified list of various synonyms for “alcoholic”: “sot,” “tippler,” “winebibber,” “elbow bender,” “overindulger,” “toper,” and “lushington.” The verticality of the list echoes the columns, window panes, and gated doorway as it suggests that the inactive, empty store that has been left to ruin has a plight parallel to the unseen human actors who have also fallen into homelessness and self-destruction. In another panel, discarded empty alcohol bottles are juxtaposed with the personifying words “dead soldiers” and “dead marines,” which are centered and bottom-justified to accentuate their downtrodden fates. In the mid-1970s, many men who fought in the Vietnam War found themselves in the Bowery, homeless, and turning toward alcohol for solace.

Detail. Martha Rosler, The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, 1974–75, forty-five gelatin silver prints of text and image mounted on twenty-four backing boards (SFMOMA) © Martha Rosler

While Rosler suggests connections between the plights of homelessness, alcoholism, war, displacement, and economic downturn, she avoids the language of social reform photography through redirecting the viewer to consider the framing conditions that govern how we see. Sometimes, Rosler’s language can be darkly humorous as it showcases urban and human decay. As such, she draws our attention to the invisible gaps of absent people in the scenes, as well as the ethical dilemma at the heart of the documentary tradition: to speak for another is at the same time to silence them. That silence is further perpetuated by the aestheticization of documentary photography in the context of museum display.

From The Bowery to the Museum

The Bowery suggests that the museum adds yet another inadequate descriptive system, since it further removes art from its context. Moreover, the museum participates in a socio-economic “othering” of the invisible people of the mid-1970s Bowery, a world that is presumably remote from the lives and experiences of the museum-goer. In this sense, Rosler can be included in a group of 1970s artists (including Michael Ascher, Daniel Buren, and Marcel Broodthaers) who were associated with Institutional Critique. These artists made conceptual art that drew attention to the ideologies and power structures of gallery or museum displays, particularly those tied to the project of Modernism and its immaculate ideals.” [4]

Rosler’s purposeful arrangement of the text and images into a grid in The Bowery is itself agitational. The grid is the symbol par excellence of Modernist abstraction and its attendant ideas of an autonomous (self-referential) purity of art. In pairing these two paradigms of Modernism (one a documentary, humanist tradition that promised social reform; the other a supposedly universal visual language of abstraction) and demonstrating the inadequacy of both for the then-present social moment, The Bowery is a twentieth-century Trojan horse in the house of Modernism.