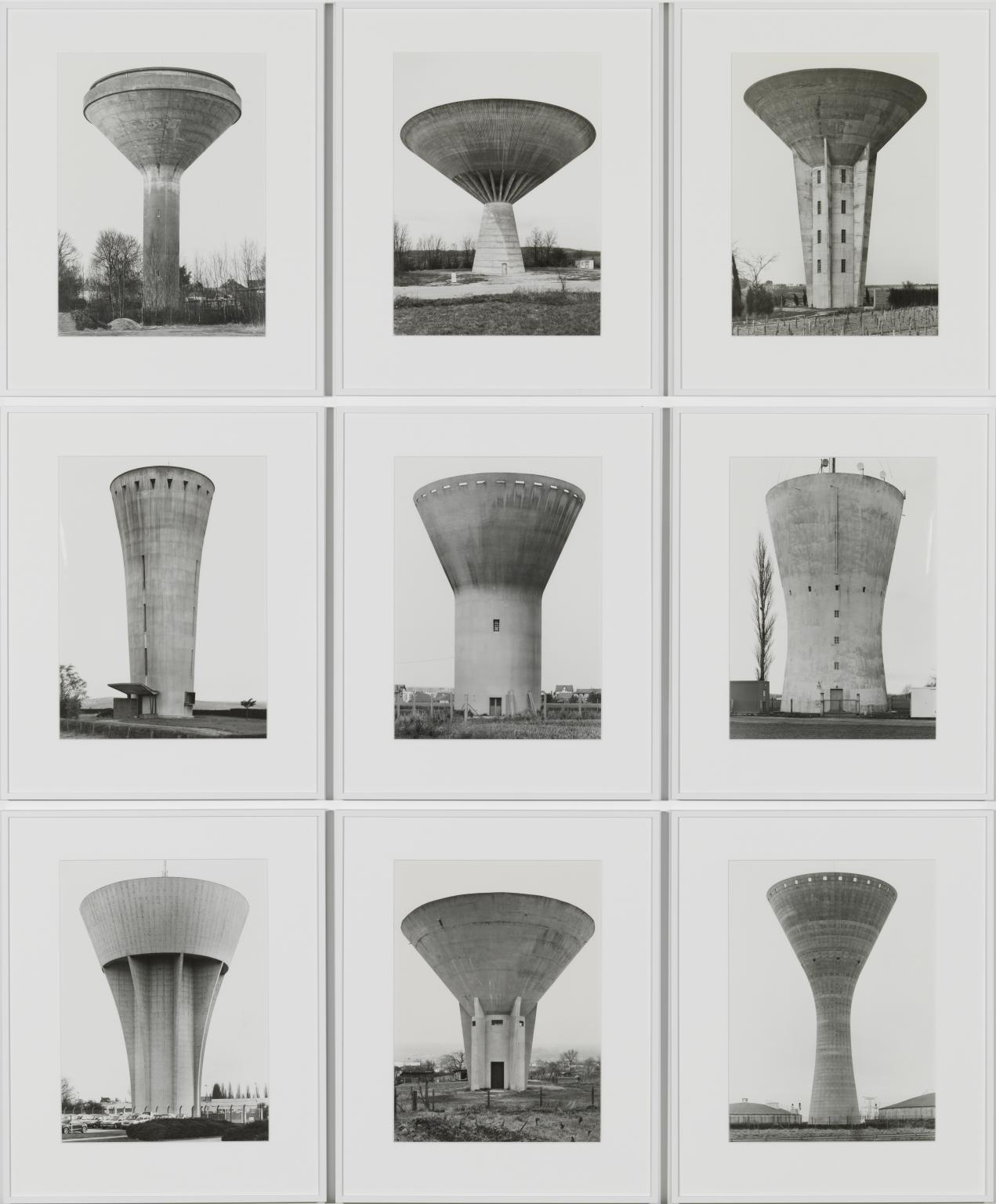

Bernd Becher, Hilla Becher, Water Towers, 1988, grid of nine gelatin silver prints, 172 × 140 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, © Estate of Bernd Becher & Hilla Becher)

In the late 1950s, photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher began documenting industrial architecture. Initially beginning in the Ruhr region of what was then West Germany and areas in the vicinity of their home and studio in Düsseldorf, they would go on to pursue their practice across Western Europe, the United Kingdom, and in the Rust Belt regions of the United States. Focused on infrastructure of the Industrial Age, the married couple and collaborators captured structures that were overlooked, declining, and would be dismantled after the onset of the Information Age in the late twentieth century. The Bechers’ systematic documentation of industrial infrastructure resulted not in singular images of historically important examples, however, but in gridded typologies: a series of images that, when presented together, emphasized the formal similarities of buildings constructed for the same function.

Bernd Becher and Hilla Becher, Anonymous Sculpture (cooling towers), 1970, grid with 30 gelatin silver prints plus diagram, 207.3 × 188.4 cm (The Museum of Modern Art, © Estate of Bernd Becher and Hilla Becher)

Typologizing noble, modest, industrial structures

Water Towers is typical of the Bechers’ approach to typological studies. Die Wassertürme, in their native German, were not the only buildings the Bechers would photograph as typological studies throughout their career as collaborators. Their subjects ranged from structures used in the coal and steel industries (mine tipples, blast furnaces) to farming (silos, framework houses, grain elevators) and modern energy infrastructure (oil refineries, gas holders, and cooling towers as seen above).

Bernd and Hilla Becher, Water Tower, Verviers, Belgium, 1983, printed 1989, gelatin silver print, 60.6 x 50.4 cm (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, © The Estate of Bernd and Hilla Becher)

They captured these places with stunning austerity and incredible consistency. The black-and-white photographs in any given typology may have been taken over the course of several years (note the date range in their Winding Towers, dated 1966–97). Despite such historical breadth, each photograph captures its subject with uniform lighting, accentuating the structure with such clarity as to convey both a common shape across the group, while highlighting individual idiosyncrasies.

Consisting of nine photographs of concrete water towers, the grid of photographs that make up Water Towers (each in a separate frame, though exhibited together as a single unit) draws attention to a common form. Form relates to function (at least in these structures), and a water tower’s function is quite simple: it holds water from an elevated structure so the weight of the water’s downward gravitational force will push the water throughout the system. As individual specimens isolated within their respective landscapes, the water towers may be unremarkable. However here, photographed vertically with a large-format, 8-inch-by-10-inch view camera, the images read as portraits, and present the viewer with an opportunity to relish the peculiarities of each patched, stained, graffiti-adorned, defiantly enduring, well-worn remnant of the Industrial Age.

August Sander, Pastry Cook (Konditor), 1928, gelatin silver print, 30.32 × 22.54 cm (Carnegie Museum of Art, Carnegie Institute)

Antlitz der Zeit (The Face of Our Time)

The Bechers’ distinct approach to their subject matter belies the historical works that inspired their photographic pursuits. Particularly important is the work of August Sander, whose 1929 book Antlitz der Zeit (The Face of Our Time) reproduced sixty photographic portraits of a myriad of contemporary Germans. Sander’s photographs of German society were organized as a spectrum of social castes, and his camera treated everyone as equals—whether they were Black, white, Jewish, a baker, a lawyer, a politician, or housing insecure. Likewise, Sander’s subjects were nearly always identified by vocation, rather than name, and were centered in the frame as they made eye contact with the camera. Like the Bechers’ work, Sander’s project was formally and technically rigorous as its multiple images drew attention to differences and similarities across his subjects. For some, such an equitable treatment of individuals across races and classes was seen as threatening, and Sander’s bookplates were confiscated and destroyed in 1933 as the Nazi Party rose to power. While the Bechers’ approach can appear, in contrast to Sander, austere and desolate, their project was likewise marked by the social and economic conditions of their time.

Bernd Becher, Hilla Becher, Water Towers, 1971–2009, grid of nine gelatin silver prints, 172 × 142 cm (Tate, © Estate of Bernd Becher & Hilla Becher)

Picturing Western Economic Unification

While the Bechers’ “portraits” of industrial buildings may appear less politically motivated than Sander’s Antlitz der Zeit, installations such as Water Towers are perhaps more politically engaged than one might at first suspect. When displayed as gridded typologies, the photographs are notably devoid of particular historical indicators or even individual senses of place. These typologies present a uniform whole, and the focus is on form and format rather than geographic and political differences. In a manner, their work is about the transnational homogeneity of industrial architecture, communicating Western industrialization as a broad social and economic force. Of note, the Bechers’ careers coincided with the creation of the European Economic Community (E.E.C.), an alliance of liberal democratic states in Western Europe that began in 1957 (the same year Bernd Becher made his first photographs of industrial buildings). The E.E.C. was the economic and political predecessor to the European Union. The Bechers’ typologies visualize capitalism and industrialization as a transnational expression.

Minimalism and “Prime Objects”

In 1972, the Bechers’ work was shown at the Sonnabend Gallery in New York. The exhibition was seen by many artists associated with Minimalism, a movement that emphasizes geometric simplicity, and industrial manufacture, thus calling attention to an object’s form and spatial context within the exhibition space. The Bechers’ rigorous, gridded, typologies were systematic, series-based works, like the work of many Minimalists. Importantly, many artists associated with Minimalism, including Robert Smithson, Mel Bochner, Carl Andre, and others, shared an affinity for the art historian George Kubler. His 1962 book The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things made the claim that all forms of art shared common denominators, or “Prime Objects.” [1] These prototypical forms of art, according to Kubler, were a means of classifying all art objects, regardless of their original cultural context. A work such as the Bechers’ Water Towers appears to express this same idea—between all of the formal differences in the nine water towers, we can perceive common attributes, a primary form.

While the Bechers’ never confirmed if they were aware of Kubler’s theories, they did make clear the importance of Ernst Haeckl’s Kunsformen der Natur (1904), a visual work that, like Kubler’s writings, used visual forms as a means for understanding the natural world. [2] Alongside their peers in the late-1960s (Smithson interpreted Kubler’s theory of the prime object as, in short, “a shape that evades shape”), we can understand the Bechers’ organizational conceit—the typology—as indicative of a shift toward ways of seeing that drew on influences from outside the canon of Western fine art practice. [3] The Bechers’ unique approach allowed for an appreciation style and beauty in forms of architecture that might be overlooked for their sheer functional and standardized appearance.

Candida Höfer, British Library I, London, 1994, 38.1 × 57.8 cm (Israel Museum, Jerusalem, © Candida Höfer)

The Düsseldorf School of Photography

With their formal and conceptual rigor, it is not surprising to know that Bernd and Hilla Becher were respected and influential teachers. From the mid-1970s through the mid-1990s, they taught together at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf—which, prior to their arrival, had not viewed photography on equal grounds with other “fine arts.” That would change as they established a rigorous and uniform aesthetic that would be known as “The Düsseldorf School of Photography,” or the “Becher School.”

The couple’s propensity for using large-format cameras resulting in precise images that would be presented in a formally austere manner, influenced many of their students’ works. An early generation of their students, including Candida Höfer, Andreas Gursky, Thomas Ruff, and Thomas Struth, became some of the most influential photographers of the 1980s and 1990s, a moment when digital photography brought into question the salience of analog photographic processes. These students’ tendency for capturing the contemporary landscape, using color photography, printing their work in a large scale, pushed the technical limits of the medium, and reflected their teachers’ contribution to the history of photography. In both their capacity as professors, and in their published and exhibited work, the Bechers’ photography showed the conceptual and formal possibilities of the medium, and the ability for landscape photography to make incisive comments on contemporary society.

Notes:

[1] George Kubler, The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1962).

[2] Hilla Becher, interview by Chris Balaschak, August 19, 2008, Duesseldorf, Germany.

[3] Robert Smithson, “Quasi-Infinities and the Waning of Space,” Arts Magazine 41, no. 1 (November 1966): p. 28.

Additional Resources

Carl Andre, “A Note on Bernhard and Hilla Becher,” Artforum 11, no. 4 (December, 1972): p. 59.

Chris Balaschak, “Between Sequence and Seriality: Landscape Photography and Its Historiography in Anonyme Skulpturen.” Photographies 3, no. 1 (2010): pp. 23–47.

Bernd Becher and Hilla Becher, Anonyme Skulpturen (Düsseldorf: Verlag Michelpresse, 1969).

Mel Bochner, “The Serial Attitude,” Artforum 6, no. 4 (December 1967): pp. 28–33.

Rosalind Krauss, “Grids,” October 9 (Summer, 1979): pp. 50–64.

Susanne Lange, Bernd and Hilla Becher: Life and Work (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2006).