Esther Bubley, Waiting for the bus at the Memphis terminal, September 1943, photograph (Library of Congress)

At the age of 22, American photographer Esther Bubley took a six-week unaccompanied Greyhound bus trip, starting in New York City and ending in Memphis, for the U.S. government’s Office of War Information (OWI). Her assignment: to document everyday moments during the country’s transition from economic depression to mobilizing for World War II, as wartime rationing of gasoline and rubber pushed the public to embrace mass transit in droves.

According to OWI documentary director Roy Stryker, Bubley and her photographer colleagues were asked to capture “pictures of men, women and children who appear as if they really believe in the USA. Get people with a little spirit.” [1] Bubley’s Bus Story series from 1943 faithfully included photographs of dutiful Americans patriotically making sacrifices—altering their modes of transportation to save gasoline and rubber for the war effort—without complaining or putting their individual needs first. Like images made by OWI peers including Jack Delano and John Vachon, Bubley’s photographs conveyed the public’s absolute faith in the ability of the United States to win the war.

In Waiting for the Bus at the Memphis Terminal from the Bus Story series, Bubley captures a large crowd of passengers waiting to board buses in Memphis—the last stop on her route. [2] Instead of forming orderly lines, people stand in a mob, remarkably unaware of Bubley’s camera, and they wait patiently. Women wear dresses, a few men are in suits and hats, and an off-duty soldier and child appear in the left edge of the frame. As the Library of Congress’s archive suggests: “They captured a range of expression—anxiety, exhaustion, boredom and enthusiasm—of people on the homefront whose lives were inextricably caught up in the national effort of willing a safe and speedy victory for ‘our boys.’” [3]

Contradicting the patriotic message

Despite the OWI’s heavy-handed instructions to capture patriotic moments of dutiful sacrifice for the war effort, Bubley includes references to Jim Crow racial-segregation laws in Waiting for the Bus at the Memphis Terminal. Although the passengers mostly appear to be white, the sign “White Waiting Room” reminds viewers that the Black passengers in the Jim Crow South were not able to legally access the same waiting room as the white bus-riders. Black people also had to ride in the back of the buses, in deference to white passengers. Jim Crow laws disenfranchised Black citizens to reverse the political and economic gains they made during the Reconstruction era, and to discourage interracial mingling. Like a few images by government documentary photographers Gordon Parks and fellow female photographers Dorothea Lange and Marion Post Wolcott, Bubley’s Waiting for the Bus at the Memphis Terminal captures the daily realities of systemic racism in the U.S. during the Great Depression and World War II.

Man entering segregated movie house, Marion Post Wolcott, Crescent Theatre (Belzoni, Mississippi), 1939, nitrate negative, 35 mm (Library of Congress)

In addition to being legally obliged to use separate waiting rooms at bus stations, and separate water fountains, Black people living in the segregationist South also had separate entrances to theatres, and were required to sit in balcony seats, apart from white audiences.

These photographs nudged the government to address the issue of legalized racial division and its incompatibility with the country’s ideology of equality. Because segregation was at odds with an optimistic ideology of rallying support for war-time domestic sacrifice, the FSA and OWI shied from circulating these images to the public unless references to racism and racial policy could be cropped out of view. [4] The OWI project grew out of the Resettlement Administration’s (RA) and Farm Security Administration’s (FSA’s) efforts to create one of the largest and most comprehensive documentary-photography projects in U.S. history covering the Great Depression. Like RA/FSA, the OWI project targeted a middle-class audience through photographs made available to the popular press and other government branches at no cost. These images still are available to the public today through the Library of Congress.

By focusing on the bus-riding working class, Bubley’s Waiting for the Bus at the Memphis Terminal also subversively points out that sacrifices were not universally made by all Americans. As Jacqueline Ellis noted, rationing hit the lower classes (who are the subjects of this photograph) harder, but it hardly altered the lives of the upper class:

She photographed women and their children, old people, and people of different races. Since they were all cramped together on the bus, she also depicted the circumstances of their economic disadvantage. [5]

In an interview, Bubley, the daughter of Russian and Lithuanian Jewish immigrants who settled in a small Wisconsin town and were in the lower-middle class, stated her preference for assignments that focused on working-class life and people. [6]

Rather than function as wholehearted war-time propaganda tools for the OWI, Bubley’s images such as Waiting for the Bus at the Memphis Terminal raise inequities of class and race in American society, issues that the government was not ready to address in the 1940s, because these inequalities undercut the rhetorical goal of the photographic project—prompting cohesive patriotic sacrifice for a common cause.

A milestone career

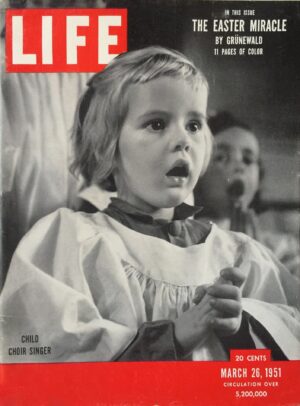

Shortly after the Bus Story series, Bubley became one of the first successful female freelance photojournalists at a time when few publications gave staff positions to women. Publications even more infrequently hired women without Ivy League degrees, or who lacked upper-class pedigrees and East Coast connections. [7] Nevertheless, bolstered by the success of Bus Story, Bubley’s work appeared in the photographic magazines Life, Look, and Ladies’ Home Journal, and was published in U.S. Camera and Modern Photography.

Bubley’s freelance work for Life included upbeat, mass-audience-friendly photo essays on celebrities such as Albert Einstein, scenes from movie sets, and images of everyday people. The photograph of a young singer was from Bubley’s first job for Life magazine, for which she photographed a choir of children aged 2 to 5. Young Choir Singer. Brooklyn, N.Y. was awarded the coveted “cover” position of the Easter issue.

Bubley’s photographs also were selected for inclusion in several exhibitions at The Museum of Modern Art, including “In and Out of Focus” (1948), “The Family of Man” (1955), and “Diogenes with a Camera” (1956), all of which highlighted important contemporary photographers. Today, her photographs are celebrated as key contributions to the golden age of photojournalism in the U.S., and are included in collections at The Museum of Modern Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., the Dallas Museum of Fine Art, the Carnegie Museum, the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, the Smithsonian Institution, the Library of Congress, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the National Museum of Women in the Arts.