The archaeological site at Knossos, with restored rooms in the background, Crete (photo: Jebulon, public domain)

Restoration versus conservation

What happens to an archaeological site after the archaeologist’s work is completed? Should the site (or parts of it) be restored to what we believe (based on evidence) it once looked like? Or should the site be protected through conservation and left as is? A visit to an unrestored archaeological site can be uninspiring—even the most lavish ancient sites can appear to be piles of unorganized stones framed by broken columns and other fragments. And while modern conservation principles insist on the reversibility of any treatment (in case better treatments are discovered in the future), in the past, conservators didn’t have the resources or science that is available today.

Knossos

The archaeological site of Knossos (on the island of Crete) —traditionally called a palace—is the second most popular tourist attraction in all of Greece (after the Acropolis in Athens), hosting hundreds of thousands of tourists a year. But its primary attraction is not so much the authentic Bronze Age remains (which are more than three thousand years old) but rather the extensive early 20th century restorations installed by the site’s excavator, Sir Arthur Evans, in the early twentieth century.

Archaeological restorations offer important information about the history of a site and Knossos doesn’t disappoint—one can see the earliest throne room in Europe, walk through the monumental Northern entrance to the palace, marvel at colorful wall paintings and enjoy the elegance of a queen’s apartments. All these spaces, however, are the result of extensive, contentious and, in some cases, damaging restoration. Knossos asks us to consider how we can preserve an archaeological site, while at the same time providing a valuable, educational experience for visitors that nonetheless remains true to the remains.

Considering Evans’ reconstructions

The Evans restoration at Knossos are important for several reasons:

1. If Evans hadn’t worked to preserve and restore so much of Knossos beginning in 1901, it would have undoubtedly been largely lost.

2. The restoration of the site undertaken by Evans, with its elegantly painted Throne Room (below) makes very real our historical understanding, originally revealed by Homer, of the power and prestige of the kings of Crete.

3. The beautiful, although sometimes inaccurate, restorations of architecture and wall paintings by Evans evoke the elegance and skill of Minoan architects and painters.

These are the undeniable benefits of Evans’s restorations and among the aspects of a visit to Knossos that everyone values. It is the smooth corniced walls, bright paintings, and whole passages stepped with balustrades at Knossos that the post cards, camera snaps, and human memory preserve, and that has translated into important support for the site—intellectually, politically, and financially.

Throne Room, Knossos (photo: Olaf Bausch, CC BY 3.0)

At the same time, the Evans restorations are problematic. In some cases, what is restored does not accurately reflect what was found. Instead, a grander, and more complete, experience is presented. For example, when you visit Knossos, because of the way it is reconstructed, it is very easy to believe that all that was ever found there was a Late Bronze Age palace.

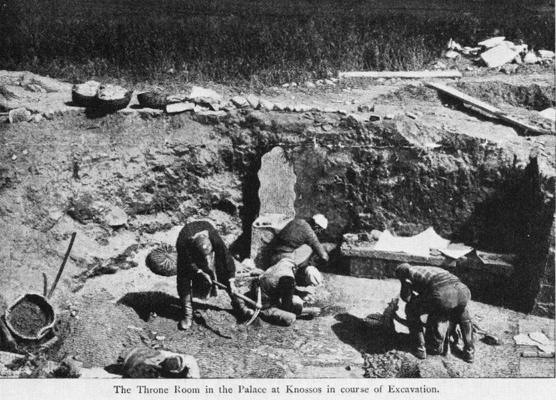

Throne Room excavations at Knossos, from the title page of a brochure appealing for support issued by the Cretan Exploration Fund (1900)

Evans’s restoration of the Throne Room (and much else at the site) privileges the Late Bronze Age period of its history. The typical visitor likely won’t grasp that the Throne Room dates to the latest phase of Knossos—the end of the 2nd millennium B.C.E., though the site was occupied nearly continuously from the Neolithic to the Roman era (from the 8th millennium B.C.E. to at least the 5th century C.E.).

The power of Evans’s interpretation and reconstruction of the site as purely Minoan—the product of the indigenous culture of that island—is very much still with us despite the fact that much has changed about how art historians and archaeologists understand the different periods of construction at Knossos. Today, much of its final plan and form, which Evans reconstructed (including the Throne Room and most of the frescos), are understood as being of Mycenaean construction (not Minoan). Although this information is noted in texts mounted at the site, it is too often overlooked by visitors.

Contemporary view of Knossos looking southwest from the Monumental North Entrance (photo: Theofanis Ampatzidis, CC BY-SA 4.0)

What is archaeological restoration?

When archaeological remains are revealed through excavation, they are often delicate and cannot survive long unprotected. Some archaeologists backfill their trenches (refill the excavated holes with the material that was removed) to help preserve remains. In other instances, architecture, graves, or the impressions left from ephemeral building materials (such as wood) are sometimes left exposed, and when this happens some sort of conservation should occur. By definition, any sort of conservation is restoration when the modern materials are layered on the ancient and made to look harmonious in form, color and/or texture. As a result, restorations are sometimes nearly indistinguishable from authentic materials, and this is where things get tricky—such as the situation at Knossos.

Before making an archaeological restoration, three essential issues must be examined:

- What specific point in a site or monument’s history will be the subject of the restoration? Many (most!) archaeological sites reflect a long occupation or use, and within that timeframe things change, are repaired, or rebuilt. What era of the site will be privileged by the restoration—and in turn, which eras of the site’s history will become harder to see and understand?

- How will future changes in the interpretation and knowledge about a site or monument be accommodated by restorations? Archaeological interpretations of sites evolve all the time, often through new discoveries elsewhere. Restorations, in order to remain accurate, need to take into account potential new scholarship that can change the history or meaning of a site or monument.

- Lastly and most importantly, restorations must be non-destructive and reversible. The first role of restoration is conservation. Therefore, the original remains must be entirely safe and not harmed in any way by restoration methods and materials. The reversibility of restorations not only has to do with the accommodation of changes in interpretation made above, but also with the need to leave the way open for less invasive, more gentle restoration methods in the future.

Restoration at Knossos

Aside from some gaps (for instance, during the First World War) Evans excavated at the site of Knossos each year from 1900 to 1930. Restoration of the architectural finds began almost immediately and can be divided into three phases, each characterized by the architect Evans hired to do the work. These three men, Theodore Fyfe, Christian Doll, and Piet De Jong, each had very different restoration philosophies.

Phase 1: Theodore Fyfe

From 1901 to 1904, a young architect by the name of Theodore Fyfe was charged with the restorations at Knossos. It is likely that Evans hired him because the winter of 1900/01 had damaged the newly exposed Throne Room—the most important space excavated during that first season at the site.

Fyfe’s work at Knossos can be characterized by two things. First of all, he was devoted to the concept of minimal intervention. Second, when intervention was necessary, he made great efforts to use materials authentic to the Bronze Age structure (wood, limestone, rubble masonry) and even to use Bronze Age construction techniques, which he was able to glean from his onsite work. Clearly Fyfe was highly concerned about the truthfulness of his interventions and reconstructions; the only exception to this was his construction of modern-style pitched roofs to protect the Throne Room and the Shrine of the Double Axes.

Phase 2: Christian Doll

The second phase of restoration work at Knossos dates from 1905 to 1910, and was directed by Christian Doll. The first conservation work to which Doll had to attend to in 1905 was that of Fyfe’s. Essentially, Fyfe’s zeal to use authentic materials resulted in failure: he neglected in many cases to treat timbers before their use and he tended to use softwoods rather than hardwoods (all of which lead to rot). Also, rain was a destructive force in the winters, especially when it ran through newly exposed parts of the site. Doll’s first and most important project was to stabilize and reconstruct the Grand Staircase to its original four story height. This was an extremely difficult job as the exact nature of the ancient design eluded both him and Fyfe, so a certain amount of improvisation was needed. And, because the weight of the structure was so great, Doll used iron girders (imported from England at great expense) covered in cement to make them look like ancient wooden beams.

Doll’s approach to conservation was still anchored in preserving the excavated remains. However, Doll was no fan of the authentic materials used by Fyfe, as he saw how they had failed to preserve the many areas where they had been employed. Instead, Doll constructed structural systems based on techniques used in London at the time. Moreover, he employed contemporary architectural materials, such as the iron girders mentioned above, as well as concrete (the first use of this material at Knossos).

Phase 3: Piet De Jong

The third phase of conservation work was executed over a longer period of time, from 1922 to 1952, by Piet De Jong. The vast majority of what Knossos looks like today, with large passages of reconstructed walls and rooms, is his work.

Three main elements characterize De Jong’s work at Knossos. The most prominent was his use of iron reinforced concrete. In the twelve years between Doll’s and De Jong’s work, the use of reinforced concrete had grown in popularity because of its speedy construction, its relative cheapness, and its ability to be molded into nearly any shape. It was also thought to be nearly indestructible.

Another essential characteristic of De Jong’s work at Knossos was his use of reinforced concrete to construct parts of the palace beyond what had been found—some passages were based on archaeological evidence, some were not (the bases of these reconstructions came from Evans himself).

De Jong often did not merely end walls at the height of their discovery but would either finish them off with a flat roof and cornice, often decorated with double white horns (what some contemporary wall paintings of Bronze Age houses looked like), or would leave the top edge of walls with irregular stones, evoking a picturesque, antique view. When a complete vision of ancient Knossos could not be reconstituted, a romantic one was built instead.

South Propylaeum, Knossos (photo: Stegop, CC BY-SA 4.0)

The reconstruction of the interior decoration of the throne room was executed during this period and similarly exhibits a combination of the truthful reflection of archaeological remains and Evans’s creativity.

Lastly, an important characteristic of De Jong’s restorations was the placement of reproductions of wall paintings around his newly built spaces. Some paintings were placed very close to their findspots and therefore aimed at a more authentic reconstruction, while other paintings were reconstructed at some distance from where they had been discovered.

The question remains: why did Evans encourage De Jong’s radical approach to conservation, especially after two more conservative predecessors? Several reasons are at play, no doubt. The first, and possibly the most important, is the condition of Knossos after almost eight years of abandonment during the First World War. Aside from the wild overgrowth of weeds, there was much weather-related and other damage. However, the parts of the site that had been roofed (such as the Throne Room and the Shrine of the Double Axes) and sections that were more intact (such as the Grand Staircase), were in excellent shape and this no doubt convinced Evans of the importance of aggressive conservation work. Second, the iron-reinforced concrete which De Jong proposed to use was inexpensive and could be employed quickly. Third, Evans, in a masterful anticipation of the desires of future tourism, aimed to make a site that would vividly conjure the culture he had discovered, as much evocative and picturesque as historically accurate.

Conservation at Knossos after Evans

It is only fair to reflect upon the restorations of Knossos within their historical framework. The aims, methods, and materials used in restoration at the site over a period of some sixty years changed, reflecting a long list of crises, constraints, theories, and desires. Perhaps most significant, however, was Evans’s overriding conviction that the conservation of Knossos was an obligation born out of its great antiquity and unique importance. He knew this from his own Edwardian education, British colonial outlook, and his twenty-four year directorship of the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford. Evans was keenly aware of how intimately connected the teaching of Knossos’s history was with how it was presented on site. He made Knossos into a museum and a showcase for the newly discovered Aegean Bronze Age chapter of ancient history and the earliest example of cultural tourism, today a mainstay of public historical education—not to mention local economies. Evans did it first at Knossos.

Conservation at Knossos has continued since De Jong’s work, although with new challenges. The most recent conservation work on the site has been focused largely on repairing Evans’s reconstructions. Despite a belief that reinforced concrete would last indefinitely, it has proven to be susceptible to the wet Cretan winters, crumbling and allowing for rust on the interior ironwork. In other areas the reinforced concrete proved to be structurally unsound.

Visitors to Knossos, 2016, photo: Neil Howard, CC BY-NC 2.0

In addition, the steady increase of tourist traffic since the 1950s has meant growing stress on both the original architecture of Knossos as well as its reconstructions. Sustained foot fall, increasing weight load as well as touching and sitting, is increasingly destructive. To combat this, the Greek Archaeological Service, under the Greek Ministry of Culture and Sports, has closed off large sections of Knossos and generally restricted circulation on the site. In the 1990s it conducted extensive conservation of both ancient and modern structures as well as building new corrugated plastic roofing. At present the Service is working on a visitor management plan for the site and the Greek government has applied to UNESCO for World Heritage Status for Knossos as well as four other Minoan palatial sites which would afford much needed support for ongoing conservation efforts.

Additional resources:

Minoan Crete from The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Helbrunn Timeline of Art History