When the Spaniards arrived here, they were amazed by the architecture—but it didn’t stop them from destroying it.

Unearthing the Aztec past, the destruction of the Templo Mayor (Mexico City). Speakers: Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank and Dr. Steven Zucker

[0:00] [music]

Dr. Steven Zucker: [0:05] We’re standing in the middle of Mexico City, in what was once the sacred precinct of the Aztecs. We’re looking at the ruins of the Templo Mayor, their main temple.

Dr. Lauren Kilroy-Ewbank: [0:15] When you are on site at the Templo Mayor today, it can be a bit disorienting because the temple itself is not complete anymore. It was destroyed and buried by the Spaniards with the conquest. What you see today are the remains of this temple.

Dr. Steven: [0:31] We’ve just walked up this ramp that has taken us through layer after layer of seven building campaigns. These were undertaken by succeeding rulers.

[0:39] The previous temple would be filled over with dirt and stone rubble, and then encased in a finished stone structure, a larger pyramid, which would be then surfaced with stucco and brightly painted, and then decorated with an enormous number of sculptural forms.

Dr. Lauren: [0:56] We get a good sense of how the Templo Mayor would have looked to the Spanish when they arrived here in 1519. The Templo Mayor was a twin temple devoted to the Aztecs’ two main deities: Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and a sun god, and the god Tlaloc, who was a rain and agricultural deity.

[1:16] The Templo Mayor was part of this larger sacred precinct that included a variety of buildings, including temples to other important deities, like the feathered serpent deity Quetzalcoatl, or to the sun disc, Tonatiuh.

[1:29] When Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conquistador, arrived here in 1519, he and many of the men with him were incredibly impressed with what they were seeing. They were overwhelmed with the beauty of Tenochtitlan, or the Aztec capital city.

[1:42] One of the soldiers with Cortés wrote about his experiences. He says this, “We saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land, and that straight and level causeway going towards Mexico.

“[1:56] We were amazed on account of the great towers and temples and buildings rising from the water and all built of masonry, and some of our soldiers asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream.”

Dr. Steven: [2:08] Let’s describe for just a moment what the Spanish must have seen when they first arrived. They saw a huge double staircase that rose steeply up, and then at the top, a large platform with twin temples on the top.

[2:19] In order to get to the temples, you would have passed by, on the right, a stone altar, and on the left, a sculptural figure that showed an individual on his back with a bowl over his belly.

Dr. Lauren: [2:31] This is what’s called the chacmool, and both this individual and the sacrificial stone that you would have passed were likely used during many of the ritual ceremonies that took place during the monthly festivals. Unfortunately, today much of what was once the sacred precinct is underneath modern-day Mexico City, underneath buildings that are still standing.

Dr. Steven: [2:50] Such as the cathedral of the City of Mexico.

Dr. Lauren: [2:53] And the Plaza Mayor, or the Zócalo, all of these would have been part of the sacred precinct or the area just immediately surrounding it.

Dr. Steven: [3:00] We’ve gone inside to look at reconstructions of the Templo Mayor. The temple was intentionally destroyed. It wasn’t transformed the way that, for instance, a Catholic church might be transformed into a Protestant church. This is the actual destruction of the most sacred temple in the most sacred part of the capital city of the Aztecs.

Dr. Lauren: [3:20] Even though we have all these accounts written by Spaniards who were commenting how beautiful and amazing it was, they still razed much of the city, in particular the sacred precinct. What we do find, then, is the building on top of many of these structures using the stones that had been part of these Aztec buildings.

Dr. Steven: [3:40] The violence wasn’t just perpetrated on the people and the buildings of Tenochtitlan but other kinds of symbols. For instance, sculptures were intentionally toppled or buried.

Dr. Lauren: [3:49] You have sculptures that are then re-carved into columns. You have sculptures made by the Spaniards for Christian purposes that were clearly once Aztec sacred objects.

[4:00] Objects like cuauhxicalli, receptacles for blood or various implements for sacrifice, were sometimes transformed into baptismal fonts. If we look at the Metropolitan Cathedral, the main cathedral in the Zócalo in Mexico City, we know that some of the stones from the Templo Mayor were reused in its initial construction.

Dr. Steven: [4:17] This is a physical expression of the spiritual and political conquest. This needs to be understood within a broader context of the Re-conquest.

Dr. Lauren: [4:27] The Reconquista, or the re-conquest in Spain, is when we’re talking about Spaniards who are trying to reconquer the Iberian Peninsula from Muslims who had taken over much of the peninsula in the 8th century.

[4:40] The re-conquest ends in 1492, shortly before they’re coming to the Americas and coming into contact with people like the Aztecs. You can see, for instance, the Great Mosque of Córdoba, with a Christian church built into the center of the building as this sign of both political and spiritual conquest.

Dr. Steven: [4:58] In that case, they left the great majority of the mosque and simply built a church in the center. Here, we have almost a complete destruction of the sacred precinct.

Dr. Lauren: [5:07] If you go to Mexico City today, you can see ongoing excavations of parts of what had been the sacred precinct. Mexico is very protective of its cultural heritage. You have organizations like INAH who are responsible for these excavations and the protection of these important sites.

[5:26] Say a building is going to be taken down and something new built on top of it, or they’re constructing subway lines. INAH has the responsibility to send in archaeologists to see if there is anything there that is part of this Mesoamerican cultural heritage.

Dr. Steven: [5:43] New things are being discovered regularly. This awareness of the value of Mexico’s cultural history goes back even to the colonial period, where you have an increasing recognition of what was lost.

Dr. Lauren: [5:56] During the colonial period, you have Spaniards born in the Americas, known as Americanos or criollos, creoles. As we’re progressing throughout the colonial period, they’re becoming increasingly interested in the Mesoamerican past as a way to separate themselves from Spaniards on the Iberian Peninsula.

Dr. Steven: [6:15] Then in the postcolonial period, after Mexico wins independence, we see this interest most visibly in the 1920s, in the 1930s, in the great mural paintings of artists like Diego Rivera. Modern Mexico City is a complex layering of modern and pre-colonial history. Imagine what we’ll find in the future.

[6:34] [music]

The Coyolxauhqui Stone, c. 1500, volcanic stone, found: Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlan (Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

In 1978, electrical workers in Mexico City came across a remarkable discovery. While digging near the main plaza, they found a finely carved stone monolith that displayed a dismembered and decapitated woman. Immediately, they knew they found something special. Shortly thereafter, archaeologists realized that the monolith displayed the Mexica (Aztec) goddess Coyolxauhqui, or Bells-Her-Cheeks, the sister of the Mexica’s patron god, Huitzilopochtli (Hummingbird-Left), who killed his sister when she attempted to kill their mother. This monolith led to the discovery of the Templo Mayor, the main Mexica (or Aztec) temple located in the sacred precinct of the former Mexica capital, known as Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City).

View of the Templo Mayor excavations today in the center of what is now Mexico City (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Templo Mayor

Map of Lake Texcoco, with Tenochtitlan (at left) Valley of Mexico, c. 1519 (photo: Yavidaxiu, CC BY-SA 3.0)

The city of Tenochtitlan was established in 1325 on an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco (much of which has since been filled in to accommodate Mexico City which now exists on this site), and with the city’s foundation the original structure of the Templo Mayor was built. Between 1325 and 1519, the Templo Mayor was expanded, enlarged, and reconstructed during seven main building phases, which likely corresponded with different rulers, or tlatoani (“speaker”), taking office. Sometimes new construction was the result of environmental problems, such as flooding.

Model of the sacred precinct in Tenochtitlan (National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City; photo: Steve Cadman, CC BY-SA 2.0)

Located in the sacred precinct at the heart of the city, the Templo Mayor was positioned at the center of the Mexica capital and thus the entire empire. The capital was also divided into four main quadrants, with the Templo Mayor at the center. This design reflects the Mexica cosmos, which was believed to be composed of four parts structured around the navel of the universe, or the axis mundi.

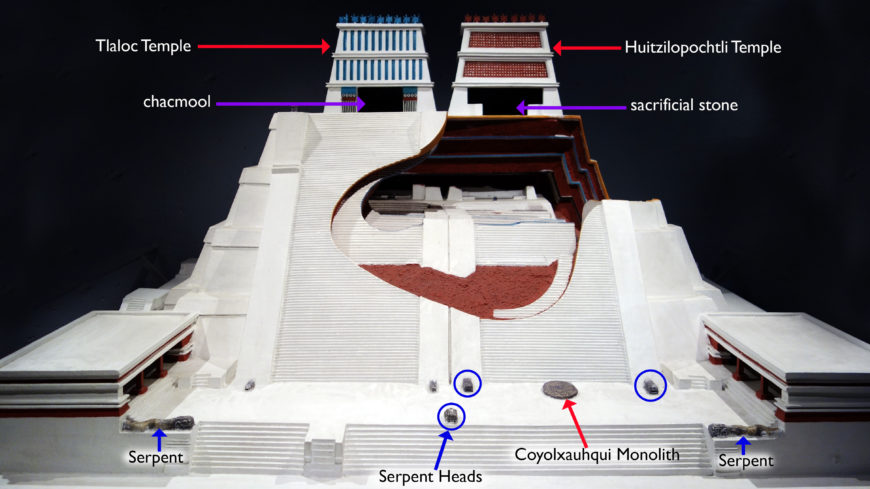

Templo Mayor (reconstruction), Tenochtitlan, 1375–1520 C.E. (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Templo Mayor was approximately ninety feet high and covered in stucco. Two grand staircases accessed twin temples, which were dedicated to the deities Tlaloc and Huitzilopochtli. Tlaloc was the deity of water and rain and was associated with agricultural fertility. Huitzilopochtli was the patron deity of the Mexica, and he was associated with warfare, fire, and the sun.

Paired together on the Templo Mayor, the two deities symbolized the Mexica concept of atl-tlachinolli, or burnt water, which connoted warfare—the primary way in which the Mexica acquired their power and wealth.

The Huitzilopochtli Temple

In the center of the Huitzilopochtli temple was a sacrificial stone. Near the top, standard-bearer figures decorated the stairs. They likely held paper banners and feathers. Serpent balustrades adorn the base of the temple of Huitzilopochtli, and two undulating serpents flank the stairs that led to the base of the Templo Mayor as well.

But by far the most famous object decorating the Huiztilopochtli temple is the Coyolxauhqui monolith, found at the base of the stairs. Originally painted and carved in low relief, the Coyolxauhqui monolith is approximately eleven feet in diameter and displays the female deity Coyolxauhqui, or Bells-on-her-face. Golden bells decorate her cheeks, feathers and balls of down (feathers) adorn her hair, and she wears elaborate earrings, fanciful sandals and bracelets, and a serpent belt with a skull attached at the back. Monster faces are found at her joints, connecting her to other female deities—some of whom are associated with trouble and chaos. Otherwise, Coyolxauhqui is shown naked, with sagging breasts and a stretched belly to indicate that she was a mother. For the Mexica, nakedness was considered a form of humiliation and also defeat. She is also decapitated and dismembered. Her head and limbs are separated from her torso and are organized in a pinwheel shape. Pieces of bone stick out from her limbs.

The Coyolxauhqui Stone, c. 1500, volcanic stone, found: Templo Mayor, Tenochtitlan (Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City; photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Coyolxauhqui stone reconstruction with possible original colors (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-SA 2.0)

The monolith relates to an important myth: the birth of the Mexica patron deity, Huitzilopochtli. Apparently, Huitzilopochtli’s mother, Coatlicue (Snakes-her-skirt), became pregnant one day from a piece of down that entered her skirt. Her daughter, Coyolxauhqui, became angry when she heard that her mother was pregnant, and together with her 400 brothers (called the Centzonhuitznahua) attacked their mother. At the moment of attack, Huitzilopochtli emerged, fully clothed and armed, to defend his mother on the mountain called Coatepec (Snake Mountain). Eventually, Huitzilopochtli defeated his sister, then beheaded her and threw her body down the mountain, at which point her body broke apart.

The monolith portrays the moment in the myth after Huitzilopochtli vanquished Coyolxauhqui and threw her body down the mountain. By placing this sculpture at the base of Huiztilopochtli’s temple, the Mexica effectively transformed the temple into Coatepec. Many of the temple’s decorations and sculptural program also support this identification. The snake balustrades and serpent heads identify the temple as a snake mountain, or Coatepec. It is possible that the standard-bearer figures recovered at the Templo Mayor symbolized Huitzilopochtli’s 400 brothers.

Ritual performances that occurred at the Templo Mayor also support the idea that the temple symbolically represented Coatepec. For instance, the ritual of Panquetzaliztli (banner raising) celebrated Huitzilopochtli’s triumph over Coyolxauhqui and his 400 brothers. People offered gifts to the deity, danced and ate tamales. During the ritual, war captives who had been painted blue were killed on the sacrificial stone and then their bodies were rolled down the staircase to fall atop the Coyolxauhqui monolith to reenact the myth associated with Coatepec. For the enemies of the Mexica and those people the Mexica ruled over, this ritual was a powerful reminder to submit to Mexica authority. Clearly, the decorations and rituals associated with the Templo Mayor connoted the power of the Mexica empire and their patron deity, Huitzilopochtli.

The Tlaloc Temple

At the top center of the Tlaloc temple is a sculpture of a male figure on his back painted in blue and red. The figure holds a vessel on his abdomen likely to receive offerings. This type of sculpture is called a chacmool, and is older than the Mexica. It was associated with the rain god, in this case, Tlaloc.

At the base of the Tlaloc side of the temple, on the same axis as the chacmool, are stone sculptures of two frogs with their heads arched upwards. This is known as the Altar of the Frogs. The croaking of frogs was thought to herald the coming of the rainy season, and so they are connected to Tlaloc.

While Huiztilopochtli’s temple symbolized Coatepec, Tlaloc’s temple was likely intended to symbolize the Mountain of Sustenance, or Tonacatepetl. This fertile mountain produced high amounts of rain, thereby allowing crops to grow.

Olmec-style mask, c. 1470, jadeite, offering 20, hornblende, 10.2 x 8.6 x 3.1 cm (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Offerings at the Templo Mayor

Over a hundred ritual caches or deposits containing thousands of objects have been found associated with the Templo Mayor. Some offerings contained items related to water, like coral, shells, crocodile skeletons, and vessels depicting Tlaloc. Other deposits related to warfare and sacrifice, containing items like human skull masks with obsidian blade tongues and noses and sacrificial knives. Many of these offerings contain objects from faraway places—likely places from which the Mexica collected tribute. Some offerings demonstrate the Mexica’s awareness of the historical and cultural traditions in Mesoamerica. For instance, they buried an Olmec mask made of jadeite, as well as others from Teotihuacan (a city northeast of modern-day Mexico City known for its huge monuments and dating roughly from the 1st century until the 7th century C.E.). The Olmec mask was made over a thousand years prior to the Mexica, and its burial in Templo Mayor suggests that the Mexica found it precious and perhaps historically significant.

Ruins of the Templo Mayor with a view of Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven, built 1573–1813, Mexico City (photo: Steven Zucker, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Templo Mayor today

After the Spanish Conquest in 1521, the Templo Mayor was destroyed, and what did survive remained buried. The stones were reused to build structures like the Cathedral in the newly founded capital of the Viceroyalty of New Spain (1521–1821). If you visit the Templo Mayor today, you can walk through the excavated site on platforms. The Templo Mayor museum contains those objects found at the site, including the recent discovery of the largest Mexica monolith showing the deity Tlaltecuhtli.